In addition to challenging inequitable representations online, this collection examines the media produced by people of color whose new media objects challenge dominant notions of race. By bringing together global and local media, this collection contributes to critical examinations of race and technology (Banks; Blackmon; Monroe; Nakamura and White; Pimentel and Gutierrez) and analyses of localized sites of critical intervention (Haas; Ito et al.; Jones; Medina “Tweeting”), and in doing so it breaks from the colonial binary, which forwards the assumption that “the First World has knowledge; the Third World has culture; Native Americans have wisdom; Anglo Americans have science” (Mignolo “Epistemic Disobedience” 2). Contributions focus on rhetorical traditions, strategies, and elements that enable and facilitate people in speaking as individuals and from communities of color while participating in the collective experience of social media networks.

Certainly, the research across fields on the digital divide (Banks; Bolt and Crawford; Compaine; Jaeger; Monroe; Norris; Ragnedda and Muschert; Servon; Warschauer) has helped call attention to the issue of access facing communities of color; however, narrowly focusing on the digital divide serves as a diversion that assuages members of the mainstream’s guilt for their lack of awareness of tech-savvy people of color and the rhetorical traditions from which they draw. As far back as 1997, Chicanx performance artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña characterized the feeling expressed by the trope of the digital divide:

I resent the fact that I am constantly told that as a “Latino” I am supposedly culturally handicapped or somehow unfit to handle high technology; yet once I have it right in front of me, I am propelled to work against it, to question it, to expose it, to subvert it, to imbue it with humor, linguas polutas—Spanglish, Frangle, gringonol, and radical politics. (192)

The low expectations of and lack of attention paid to digital compositions by people of color can be directly tied to white privilege. Mary Bucholtz explains that the “nerd” identity often associated with technology “may itself be a form of white privilege, since these practices were not as readily available to teenagers of color and the consequences of their use more severe” (96). Instances of racism online are nothing new in computers and composition scholarship (Bomberger; McConaghy and Snyder; McKee); however, the possibilities for social activism or composing digital media that somehow respond to, complicate, or bypass symbols of nonwhites in the colonial imaginary have found platforms that support alternative self-representations.

The contributors to this collection cannot and will not proclaim that access no longer remains an issue; anecdotally, we observe in our own classrooms how students of color do not always possess the best and newest technology. In Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: Searching for Higher Ground, Adam Banks addresses the dire implications for discussion beyond the digital divide because:

[It] involves both contest and silence: debate over whether there is a Divide at all…debate over whether race is a factor in whatever problems in technology access might exist; and concern that the use of a term like Digital Divide represents African Americans unfairly and does more to further the erasure of Black people by continuing to cast them as the utter outsider. (31)

The sites of analysis in this collection identify some of the ways in which radically localized sites create media that resist the erasure that comes from focusing entirely on access.

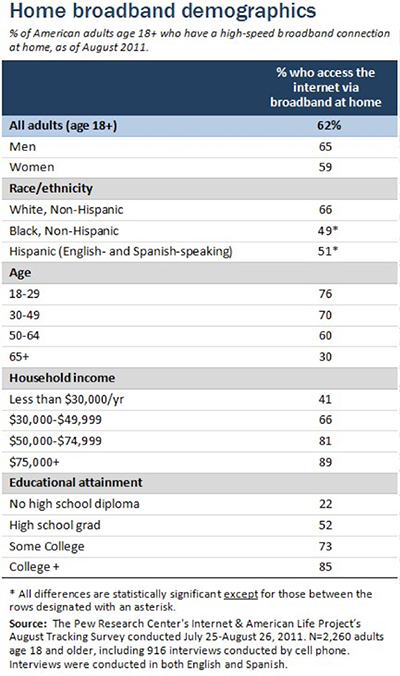

The proliferation of media created by communities of color can be linked to the innovation of and increase in access to cell phone technology. In 2012, the Pew Research Internet Project concluded that “neither race nor gender are themselves part of the story of digital differences in its current form” (Zickuhr and Smith 6). Instead, Kathryn Zickuhr and Aaron Smith point to the example of mobile phone access as one of the factors that perhaps has contributed to the decline in difference: “Even beyond smartphones, both African Americans and English-speaking Latinos are as likely as whites to own any sort of mobile phone, and are more likely to use their phones for a wider range of activities” (Zickuhr and Smith 3). The following table breaks down the percentages for access across demographics.

This collection begins to fill in the broad gap in scholarship documenting the digital literacy of people of color in online and social media. In many cases, scholars of color draw from cultural traditions in which they are entrenched or by which they are inspired, many of which predate online media and stem from the oral and aural traditions of Blacks and Latinxs (Banks; Selfe; Villanueva). The critical lens employed by researchers in this collection demonstrates what Gloria Anzaldúa describes as la facultad, or the “capacity to see in surface phenomena the meaning of deeper realities, to see the deep structure below the surface” (60). To critically engage with technology requires the capacity to see how the efficacy of different assemblages of images, sound, text, video, and animation can be, and have been, informed by diverse rhetorical traditions.

The framework for this collection is described as a decolonial methodology in part because the exigency of this collection is firmly rooted in presenting traditions of knowledge that have been marginalized and misrepresented through ideologies of racial supremacy embedded in digital practices of framing nonwhites as lacking. Contributors identify and critique the misrepresentations forwarded online and in social media to resist those narratives positioning nonwhites as “Others.” At the same time, the contributions enact an important decolonial role by presenting knowledge from rhetorical traditions that have been denied, dismissed, and ignored in favor of championing the centrality of whiteness in the myth of Western modernity.

With regard to misrepresentation and nondominant knowledge traditions, this methodology follows what Angela Haas outlines when she applies a decolonial approach to a course centered on race and technology in “Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: A Case Study of Decolonial Technical Communication Theory, Methodology, and Pedagogy.” Haas explains,

decolonial methodologies and pedagogies serve to (a) redress colonial influences on perceptions of people, literacy, language, culture, and community and the relationships therein and (b) support the coexistence of cultures, languages, literacies, memories, histories, places, and spaces—and encourage respectful and reciprocal dialogue between and across them. (297)

Although pedagogy is not a primary focus of this collection, Haas’s definition parallels how the contributions critically focus on moments when power has been exerted through race and technology to reinstantiate dominance as well as on the presentation of alternative ways of knowing. Haas’s schema also eloquently delineates the simultaneous work a decolonial methodology must perform.

By problematizing dominant narratives about cultures, literacies, and epistemologies of people of color and presenting multimodal examples of meaning-making from these overlooked traditions, this collection digitally composes an archive that has been curated to redress colonial perspectives. The attention to archives follows Ellen Cushman’s call to consider “the problems and promise of digital archives” such as the platform that Computers and Composition Digital Press offers as a curated repository for peer-reviewed research (116). We apply this decolonial methodology as we consider how multimodal compositions contribute to how “[d]ecolonial digital archives have built into them the instrumental, historical, and cultural meanings of whatever media they include” and we seek to demonstrate how “such media need to be contextualized within the social practices that lend them these meanings” (Cushman 116). These kinds of decolonial digital practices are important because they follow what Walter Mignolo calls the “decolonial path,” which shares “the colonial wound, the fact that regions and people around the world have been classified as underdeveloped economically and mentally” (3). Consciously collecting and calling attention to the digital work of people of color provides evidence that exposes the deficit narratives about these communities and technology as a part of oppressive colonial projects, which subjugate through taxonomies of authorized knowledge. This collection does not altogether “de-link” (a la Mignolo) from existing literacy, technical communication, and composition and computers scholarship; however, the contributions break from colonial narratives that dare to ask whether nonwhites have rhetorical and epistemological traditions.

The decolonial exigency for this collection undergirds the rhetorical analytic methods that can be traced throughout the contributions. Though not all the contributions self-identify as decolonial, situated methodologies in each chapter allow for resistance to the dominant narratives communicated in public social media discourse. Though sites such as Twitter can provide platforms for inequitable constructions of people of color, the social media component of the Black Lives Matter movement has also been supported by the Twitter hashtag that archives knowledge about this activism. On digital writing environments, Adam Banks makes the point in Digital Griots: African American Rhetoric in a Multimedia Age that writing is simultaneously an act of archiving, evidenced through his discussion of the digital griot as a DJ whose knowledge is curated in the crates and remixed in the composing and delivery of rhetorical excellence.

It is important that contributors to this collection identify, capture, and document prevalent forms of racist and sexist discourse and representation because these exhibits evidence the necessity of counter-hegemonic and decolonial work. Digital technology facilitates the archiving of both discriminatory and generative new media objects, which can be overlooked in the deluge of news clickbait and social media updates. By focusing primarily on online projects and social media discourse, the contributors to this collection make use of the digital book platform by highlighting important self-representational media. These new media objects remix dominant symbols and create altogether original objects that present perspectives from diverse rhetorical traditions. In both cases, this collection seeks to expose the shorthand of dominant representations as complex systems of coded messages that marginalize and subjugate. Online and social media continue to play a dual role, transmitting both mainstream discursive productions embedded with media shorthand (read: racialized assumptions) and productions by radically local sites of self-representation. Many times these self-representative media producers first must resist media that overwhelm people of color into becoming docile audiences and consumers. Media produced in radically local sites provide critical examples of hope in contrast to Hollywood’s media industrial complex (Wayne). The tension between self-representation and dominant shorthand is further complicated by the localized networks of distribution social media facilitates.

The goals for this collection are as follows:

- Highlight how social media such as Twitter circulate racist discourses that perpetuate myths of white supremacy, attack the citizenship of nonwhites, and enforce linguistic homogeneity online;

- Identify misrepresentations of and self-representations by women of color in social media and online spaces;

- Demonstrate the affordances of Twitter to provide a virtual headquarters and network while distributing information for the social movement of #BlackLivesMatter;

- Examine the literacy artifacts of communities of color that demonstrate traditions of multimodal composing that have been previously ignored;

- Reimagine linguistic difference as an advantageous technology rather than as a deficit;

- Present a digital curriculum with culturally relevant implications for Latinx students.

Description of Chapters

Examples of racist outrage online, such as the response to Coke’s “America the Beautiful” commercial, demonstrate how myths of white supremacy and linguistic homogeneity seek to maintain dominant representations and provide exigency for the chapters that follow. In line with Coke’s “America the Beautiful” commercial, Sebastien de la Cruz’s performance of the national anthem at the 2013 NBA Finals in mariachi regalia elicited racially driven outcry on Twitter. Octavio Pimental critically analyzes this social media response in “Not the King: Cantando el Himno Nacional de los Estados Unidos.”. Pimentel shows how de la Cruz’s performance of Mexican-American ethnic identity, while wearing traditional mariachi attire, drew racist responses because his appearance challenged shorthand notions about what an “American” looks like. Visually representing Mexican-American culture, de la Cruz’s appearance also raises questions about the myths of monolingualism undergirded by systemic racism. The subsequent support for de la Cruz demonstrates how social media facilitates public discourse and online activism that precipitates action in real life.

11-year-old Sebastien de la Cruz singing the national anthem before the 2013 NBA Finals:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4VF8mbM5WJ0

Twitter captures moments that highlight how dominant beliefs about race circulate through online discourse when the shorthand representations of “Americans” is unsettled. The 2014 crowning of an Indian-American Miss America provoked racist responses via Twitter because the event celebrated “American” womanhood; however, in this case, whiteness was not upheld as the ideal. Charise Pimentel’s “Miss American Terrorist: A Critical Racial Analysis of the Crowning of Miss America” evaluates this eruption of racist social media posts and demonstrates the hate perpetuated in defense of white supremacy. Comments such as “And the Arab wins Miss America. Classic,” “Ummm wtf?! Have we forgotten 9/11?”, “How the f*** does a foreigner win miss America? She is a Arab!”, and “More like Miss Terrorist” provide data for racial analysis of and discourse around the pageant, thereby informing the sociopolitical context wherein racial discourse freely flows through media. To frame this discussion, this chapter highlights the Smithsonian digital exhibit “Beyond Bollywood: Indian Americans’ Shape the Nation,” a physical museum and online space that encourages viewers to learn more about Indian-American heritage and contributions to the U.S. By providing accurate representations, Charise Pimentel juxtaposes the histories of a community and how they are willfully misrepresented in social media.

Moving from a pageant that has historically objectified women to one of the most well-known misrepresentations of womanhood, Alexis McGee analyzes the representations of racial Others in the world of Barbie® online. McGee’s “Barbie® Goes Abroad: Feminism, Technology, and Stereotypes” problematizes the enduring legacy of the Barbie doll in online space despite the false ideal of female representation. McGee specifically examines Mattel’s Dolls of the World collection, which embraces stereotypes about race, gender, and sexuality. She explains that the designs of the World collection rely on phenotypical characteristics of dominant Western hegemony to (mis)represent non-Western cultures, and hypersexualized images of hypereffeminate women. This chapter raises important issues about cultural representations shared across geographical borders, where inherently false depictions of women move from the West to non-Western cultures, reaffirming colonial influence. The critical analysis of these influential misrepresentations of feminine ideals reveals how womanhood is falsely constructed; however, women of color have also taken advantage of online space to underscore the accomplishments of individual women.

Moving on from the misrepresentation of nonwhite women online, the contributors focus on the self-representation of people of color and how communities of color use social and online media in line with how these rhetorical traditions have carried out activism, storytelling, and other literacy practices. In “‘Essence of Mom 2.0’: Media, Memory, and Community across an Extended African American Family,” Lillie Jenkins and Julia Voss use a case study to focus on the production processes and purposes behind a literacy artifact Jenkins created to memorialize her mother within her large extended family. Jenkins’s multimodal booklet uses her mother’s letters, folk tales, dreams, stories, poems, photographs, and hand-crafted folk art objects (quilts, home decor, and embroidery) to document her mother’s role and influence on the family’s history. The chapter draws on Jenkins’s long-standing interest in photography; her postsecondary and graduate work in communications; her participation in a university/community collaborative video project documenting the black church’s role as a sponsor of literacy; and her strategic (nonmatriculated) enrollment in a subsequent university course in advanced digital media production. Jenkins’s booklet, as an artifact that remediates and recirculates her mother’s texts, 1) illustrates the complex network of literacy resources distributed across home, school, and work spheres that underpin such self-sponsored media production in minoritized communities, and 2) points to how this kind of grassroots media production has the potential to record and extend community-based literacy practices and the beliefs/stories contained within them using both textual and face-to-face interaction.

One of the most explicit ways in which communities of color have been able to communicate stories about police brutality and facilitate collective action against the over-policing of people of color has been through the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Examining how Twitter provides a digital writing environment for social change, Miriam Williams conducts a quantitative rhetorical analysis of conversations about African-American online activism in “#BlackLivesMatter: Tweeting a Movement in Chronos and Kairos.” Williams examines how African-American activists on Twitter use this social media platform as a virtual headquarters for a movement against excessive police force and over-policing within African-American communities. She does “argue[s] not about whether these people of color are innocent or guilty, but [that they are] unarmed and dead” (Williams). Williams reflects on her role as a participant-observer with Twitter and the transformative effect of #BlackLivesMatter in informing followers of developments that may not be covered by cable news or other media. While Twitter has provided a digital headquarters for social activism, it has also served as an archive of racist discourse circulated in response to publically discussed events. Looking at tweets coded with the hashtag, Williams offers quantitative data related to Twitter users’ support of or disagreement with the #BlackLivesMatter movement.

The use of hashtags for social activism demonstrates how communities of color employ technologies that support culturally relevant literacy practices. For Latinxs in the U.S., translanguaging is a literacy practice with implications in digital spaces. In “Multilingualism as Technology: From Linguistic ‘Deficit’ to Rhetorical Strength,” Laura Gonzales makes the argument for translation as a technology–a technology used by multilinguals in both physical and digital spaces. Drawing on discussions about linguistic diversity (Composition Forum and the Blog Carnival on language and multimodality that Gonzales edited for the Sweetland DRC), Gonzales argues that individuals who move between languages to communicate have an inherent rhetorical dexterity that can teach us about language, technology, writing, and culture. Gonzales’s site of analysis is the Language Services Department at the Hispanic Center of Western Michigan, and she articulates how multilinguals strategically move between English and Spanish in pursuit of specific goals. In this chapter, Gonzales highlights what she terms “translation moments” to demonstrate how translation functions as a technological and rhetorical activity that is often overlooked in the deficit models used to describe multilinguals in academic and professional settings.

Traditional forms of technology, such as digital multimodal compositions by communities of color, also reveal important literacy traditions that offer potential for digital writing pedagogy. In “Digital Latinx Storytelling: Testimonio as Multimodal Resistance,” Cruz Medina draws on the culturally relevant Latinx storytelling practice of testimonio (testimony), which has a tradition of “speaking truth to power” in Latin America. Specifically, Medina applies the Latinx Critical Race (LatCrit) methodology for producing digital testimonio practices that intersect with digital storytelling and non-digital storytelling traditions in rhetoric and composition. Medina includes a digital testimonio that comes from his professional blog (AcademiadeCruz.com), to which Latinx scholars in rhetoric and composition have contributed posts that illuminate interconnections among storytelling practices. In addition, Medina includes his own example of digital testimonio as a site of analysis that was inspired by his vignette in College Composition and Communication’s 2013 special issue on the profession. Digital testimonio offers a culturally relevant new media framework that addresses issues of audience, genre, recursivity, and digital writing. At the same time, digital testimonio presents individual Latinx perspectives while contributing to a broader understanding of diverse Latinx experiences across the changing face and demographics of the U.S.

Works Cited

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lute, 1987.

Ahsante the Artist. “I, Too, Am Harvard.” YouTube. 3 March 2014. Web. 1 April 2014.

Banks, Adam J. Digital Griots: African American Rhetoric in a Multimedia Age. Carbondale: SIU-Press, 2010. Print.

---. Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: Searching for Higher Ground. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2006. Print.

Blackmon, Samantha. “(Cyber) Conspiracy Theories? African-American Students in the Computerized Writing Environment.” Labor, Writing Technologies, and the Shaping of Composition in the Academy. Eds. Pamela Takayoshi and Patricia Sullivan. Cresskill: Hampton Press, 2007: 153-66. Print.

Bolt, David B. and Ray Crawford. Digital Divide: Computers and Our Children's Future. New York: TV Books, 2000. Print.

Bomberger, Ann M. “Ranting about Race: Crushed Eggshells in Computer-Mediated Communication.” Computers and Composition 21.2 (2004): 197-216. Print.

Bucholtz, Mary. “The Whiteness of Nerds: Superstandard English and Racial Markedness.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 11 (2001): 84-100. Print.

“Coca-Cola #AmericatheBeautiful 2014 Super Bowl Commercial.” YouTube. 1 Jan 20 2017. Web. 7 Aug 2017.

Compaine, Benjamin M. The Digital Divide: Facing a Crisis or Creating a Myth? Cambridge: MIT P, 2001. Web.

Cushman, Ellen. “Wampum, Sequoyan, and Story: Decolonizing the Digital Archive.” College English 76.2 (2013): 115-135.

De la Cruz, Sebastien. “National Anthem by Sebastien El Charro de Oro.” YouTube. 10 Jan 2013. Web. 1 Feb 2014.

Feagin, Joe. Systemic Racism: A Theory of Oppression. New York: Routledge, 2013. Print.

Gómez-Peña, Guillermo. “The Virtual Barrio @The Other Frontier (or the Chicano Interneta).” Clicking In: Hot Links to a Digital Culture, ed. Lynn Hershman Leeson. Seattle: Bay Press, 1996: 173-85. Print.

Haas, Angela M. “Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: A Case Study of Decolonial Technical Communication Theory, Methodology, and Pedagogy.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication 26.3 (2012): 277-310. Print.

---. “Wampum as Hypertext: An American Indian Intellectual Tradition of Multimedia Theory and Practice.” Studies in American Indian Literatures 19.4 (2008): 77-100. Print.

Jaeger, Paul T. Disability and the Internet: Confronting a Digital Divide. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2012. Print.

Jones, Natasha N. “The Importance of Ethnographic Research in Activist Networks.” Communicating Race, Ethnicity, and Identity in Technical Communication. Eds. Miriam Williams and Octavio Pimentel. Amityville: Baywood Publishing, 2014: 46-59. Print.

Ito, Mizuko, Sonja Baumer, Matteo Bittanti, Danah Boyd, Rachel Cody, Becky Herr Stephenson, Heather A. Horst, Patricia G. Lange, Dilan Mahendran, Katynka Z. Martinez, C. J. Pascoe, Dan Perkel, Laura Robinson, Christo Sims, and Lisa Tripp. Hanging Out, Messing Around, and Geeking Out: Kids Living and Learning with New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010. Print.

Matsuda, Paul Kei. “The Myth of Linguistic Homogeneity in US College Composition.” College English (2006): 637-51. Print.

McConaghy, Cathryn, and Ilana Snyder. “Working the Web in Australia.” Global Literacies and the World Wide Web. Eds. Gail Hawisher and Cynthia Selfe. New York: Routledge, 2000: 74-92. Print.

McKee, Heidi. “‘YOUR VIEWS SHOWED TRUE IGNORANCE!!!’: (Mis)Communication in an Online Interracial Discussion Forum.” Computers and Composition 19.4 (2002): 411-434. Print.

Medina, Cruz. “The Family Profession.” College Communication and Composition 65.1 (2013): 34-36. Print.

---.“Tweeting Collaborative Identity: Race, ICTs and Performing Latinidad.” Communicating Race, Ethnicity, and Identity in Technical Communication. Eds. Miriam Williams and Octavio Pimentel. Amityville: Baywood Publishing, 2014: 63-86. Print.

Mignolo, Walter D. “Delinking: The Rhetoric of Modernity, the Logic of Coloniality and the Grammar of De-Coloniality.” Cultural Studies 21.2-3 (2007): 449-514. Print.

---. “Epistemic Disobedience, Independent Thought and De-colonial Freedom.” Theory, Culture & Society 26.7 (2009): 1-23. Print.

Monroe, Barbara J. Crossing the Digital Divide: Race, Writing, and Technology in the Classroom. New York: Teachers College Press, 2004. Print.

Nakamura, Lisa, and Peter Chow-White. Race after the Internet. New York: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Norris, Pippa. Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001. Print.

Pimentel, Octavio, and Katie Gutierrez. “Taquerors, Luchadores, y los Brits: U.S. Racial Rhetoric, and Its Global Influence.” Communicating Race, Ethnicity, and Identity in Technical Communication. Eds. Miriam Williams and Octavio Pimentel. Amityville: Baywood Publishing, 2014: 87-99. Print.

Poniewozik, James. “Coca-Cola’s ‘It’s Beautiful’ Super Bowl Ad Brings Out Some Ugly Americans.” Time.com. Time Inc. 2 Feb 2014. Web. 1 Jun 2016.

Ragnedda, Massimo, and Glenn W. Muschert. The Digital Divide: The Internet and Social Inequality in International Perspective. Abingdon: Routledge, 2013. Web.

Selfe, Cynthia L. “The Movement of Air, the Breath of Meaning: Aurality and Multimodal Composing.” College Composition and Communication 60.4 (2009): 616-663. Print.

Servon, Lisa J. Bridging the Digital Divide: Technology, Community, and Public Policy. Malden: Blackwell Pub, 2002. Print.

Stokes, Sy. “The Black Bruins (Spoken Word).” YouTube. 4 Nov. 2013. Web. 3 March 2017.

Van Sertima, Ivan. “Trickster: The Revolutionary Hero.” Talk That Talk: An Anthology of African American Storytelling. Ed. Linda Goss. Clearwater: Touchstone, 1989: 103-112. Print.

Villanueva, Victor. “‘Memoria’ Is a Friend of Ours: On the Discourse of Color.” College English 67.1 (2004): 9-19. Print.

Warschauer, Mark. Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003. Web.

Wayne, Michael. “Post-Fordism, Monopoly Capitalism, and Hollywood's Media Industrial Complex.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 6.1 (2003): 82-103. Print.

Young, Morris. Minor Re/Visions: Asian American Literacy Narratives as a Rhetoric of Citizenship. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2004. Print.

Zickuhr, Kathryn, and Aaron Smith. “Digital Differences.” Pew Research Internet Project. Pew Research Center. 13 Apr. 2012. Web. 23 Apr. 2014.

![Youtube video: The Black Bruins [Spoken Word] - Sy Stokes](img/introduction/fig1.png)