Barbie Goes Abroad: Critiquing Feminism, Technology, and Stereotypes in the Narratives and Social Media Strategies of Barbie

Much has been said about Barbie: Her style is timeless, and her look is iconic. However, this technological innovation is slow to represent the many multicultural consumers invested in her product today. Because this product propagates certain features arguably denoting beauty and promotes stereotypes in some of the other Barbie lines, consumers can no longer afford to passively see Barbie as a progressive image; rather, we must begin to challenge the images and strategies behind the markets producing consumer goods.

This work aims to contextualize current manifestations of this classic model for feminist propaganda. Although Mattel has amazingly been able to maintain Barbie as a successful international product loved by millions, I argue that Mattel’s coalescing of contemporary technology and marketing actually demonstrates ways in which Barbie does not fit the commonly accepted notion of the everyday or every girl narrative built into her product. Thus, focusing on ways in which Barbie—the image and the narrative—produces forms of racial shorthand will allow us to understand this rhetoric across multiple spaces regardless of medium.

To effectively integrate both digital and print contributions to the deconstruction of Barbie as the every day/girl, I weave my personal testimony as well as my mother’s into this work. Documenting these counternarratives acts as resistance to passive consumer spending. This chapter is primarily broken into three sections. First, I contextualize Barbie within contemporary American consumerism. This section, “Introducing Barbie… Again: Race and Gender Assumptions in Barbie Collections,” traces the history of Barbie. The second section, “Change of Address: Critical Analysis of Barbie and Moving Qualifications,” uses critical discourse analysis to deconstruct current narratives of Barbie portrayed within technology and effectively support the counternarrative. Here I focus on social media literacy and the campaign Mattel used to initiate interest in Barbie. This campaign hints at the re-launch of the Dolls of the World collection, which is explored in the last section of analysis. The last portion, “Barbie and the Construction of Non-White Ethnicities,” critiques two Barbies from this relaunched line, establishing more evidence for the racial shorthand of Barbie.

I am fully aware of the irony of the fact that I am discussing Barbies when I myself owned and played with Barbies. I understand that Barbie culture is still very much a part of mainstream society—with body augmentation and in hip-hop discourses with rap personas such as Nicki Minaj—in which I still remain entrenched and delving into the implications of images and performances for consumers and do not foresee that research coming to an end any time soon. However, with technology, Barbie culture continues to grow and splinter into many variations of discourses. The rapid dissemination of information by way of media makes the way we as consumers digest and internalize that information, those images, and those performances crucial.

The recent American recession caused largely in part by the 2008 housing crisis has left fiscal responsibility as one of many central consumer concerns. Questions as to which products are the best, or most effective, for their price remain prominent as we move into the realities of debt ceilings, budget cuts, and tax reforms. But some products continue to be in more demand than others regardless of economic conditions. Other products, such as shipping containers repurposed as storefronts and mini ecological niches for ecology studies, challenge consumers to rethink methods of manufacturing and sustainability. This reevaluation of products should affect not only transnational, macro-impacting goods such as fueling resources, but also the ways in which commodities are marketed as a reflection of cultural ideology. Basic necessities are a matter of priority, but other material goods such as accessories, books, and toys are pushed aside as afterthoughts, thus lending themselves to being marketed through uncritical reception and subversive, passive forms of oppression such as ethnic, sex, gender, and ableist bias. When such niceties are consumed, it is important to understand the values and ideologies the products communicate.

Accompanying the country’s monetary ebb and flow is a rise in critical body consciousness. Policies, legislative rulings, and regulations on issues such as family planning/welfare reform, same-sex marriage, and grand jury indictments affecting personal choices, lifestyles, and essential being are beginning to be challenged, questioned, and persecuted because of cultural representation and socially constructed ideologies in America. But how are representations and ideologies of marginalized people being sculpted into negative images such that resistance is leading to push-back on national and international levels? One short answer is through toys. Of course, toys are not the only component of this equation; they are, however, a factor. Toys have been found to mimic and reflect cultural attitudes imposing positive or negative ideas of the self; a classic case of such negative psychological disidentification was chronicled via Kenneth and Mamie Clark’s doll test, which aided in the desegregation of schools (“Kenneth and Mamie Clark”) and whose psychological impact still holds today. The American Psychological Association has recently created a task force to investigate and campaign against the harmful effects of certain kinds of female representation, particularly on young girls (Report of the APA). The ubiquity with which dolls are distributed should influence a reevaluation of the products’ representation. As of now, dolls such as Barbie are marketed as a fantastical yet relatable character for everyone, but where are the working-mom Barbies, the charged-with-a-crime-because-of-ethnicity-or-socioeconomic status Barbies, the activist/community-service Barbies?

Recently, Americans have been forced to reassess cultural representation in more ways than one. In the past decade America elected its first person of color to be president, witnessed apparent effects of climate change, changed the engineering of technology, and suffered one of its most drastic economic crises since the Great Depression. Summer 2015 brought major political issues in terms of sociocultural-geopolitical self-representation, but one company might have capitalized on America’s progressive movement while still retaining subtle, passive forms of racial shorthand.

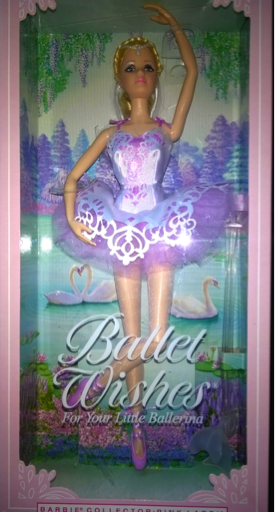

On June 30, 2015, it was announced to the general public—by way of social media like Twitter, Instagram, and e-magazine articles from the Washington Post and the New York Times—that Misty Copeland was now the American Ballet’s first African American female principal dancer. In the very whitewashed and elitist field of American ballet, Copeland broke barriers. It was during this time that Mattel produced Ballet Barbie (Figure 1). This pink-labeled collector’s item takes advantage of the recent excitement surrounding ballerinas and Broadway; however, this entry-level collector’s edition does not reflect the advancement Copeland made, offering just the traditional image of a classical dancer that so many children, myself included, grew up idolizing.

Copeland even starred as the lead dancer in a production of Swan Lake. Seemingly coincidently, Barbie here is marketed as being in the same production. It could be that Swan Lake is a typical summertime production, but I think this is more than accidental. There are other versions of this specific Barbie, but there are few differences between them, wardrobe and hair color being the most prominent.

The lack of self-reflection seen within the recent production of Barbie reminds me that Mattel’s premier toy development is neither new nor just a toy; the doll grows, changes, reacts, pushes the cultural atmosphere from which it is produced and by which it is imposed upon. Barbie not only adapts to the society at large by way of marketing, but also leaves enough space for the consumer to create superficial lives for the dolls and imagined lives for the consumer. The problem is that Barbie and her friends will always have a prescribed initial narrative, whether that is one of ethnicity, gender, able-bodiedness, class, or something else. The prepackaged story line shapes the doll's interactions with the buyer, thus informing the created consumer narrative of a remixed reflection of reality.

Moreover, the dangers created by these prepackaged personas can last beyond childhood. Challenges faced by the “every-day” girl may not be fully realized when creating parallel narratives engaging Barbie and her friends (and accessories), but the lasting effects of personal connection and representation do not necessarily diminish. In 2010, my grandfather passed away; I never really met him. My mom wanted to reclaim only one thing from his possessions after he passed: her Barbies. It was a long shot; my mom and grandfather had not been in contact since maybe the 1970s. It was clear, however, that her connection to Mattel’s products was strong. I asked why she wanted them so much, and she told me that playing with her Barbies was one of the only happy memories of her childhood and that some of them were collector’s items. Of course my mom had other happy memories, but the fact that she still holds on to the fantastical, nostalgic feelings associated with this iconic item demonstrates what many consumers find in it: an escape from reality by means of recreating existence.

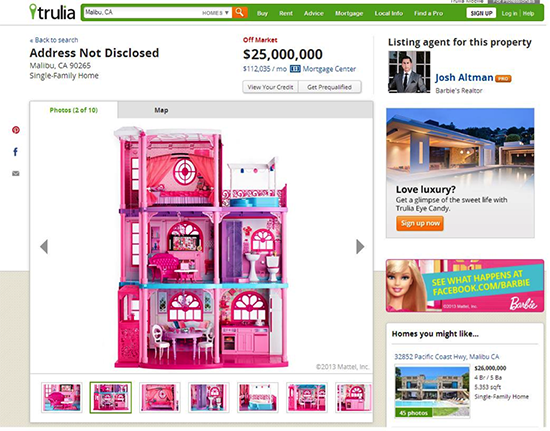

Barbie is simply not an “every girl” even though Mattel markets her as one. Barbie is a doll that comes with various occupations, accessories, and backgrounds, most notably her Malibu Dreamhouse. Sold separately from the doll, the Malibu Dreamhouse is the play mansion, the vacation home, but it comes at a hefty price not every girl can afford. I remember coming home from the toy store as a little girl with Barbie’s Magical Motor Home instead of the Malibu Dreamhouse because I could not afford that piece of prime real estate. Even a generation before, when Malibu Barbie came out during 1970-1976 (D’Amato 50), my mother couldn’t afford her Dreamhouse for my older sister; she herself had never had one, and nor did my sister or I. She bought a cheaper off-brand tin dollhouse to supplement my sister's playtime with Barbie (Figure 2). As for Barbie’s living accommodations, let us call my motor home what it was, an RV: a vehicle promoted to a camper. It was my low socioeconomic status that limited Barbie’s home to an RV when other Barbies lived more lavishly. What the motor home really represented, from a capitalist perspective, was that Barbie had options for vehicles. She had a motor home, and let us not forget about her convertible, in addition to her owning and maintaining her dream home that is, two cars and a permanent luxury residence. The average income for people in the United States in 1989, when I was a young girl, the $30,939 was not nearly enough to allow someone to afford the lavish hyperreality portrayed by Barbie’s accoutrements. Even Barbie’s real-life counterparts, the 18-to-25-year-olds, averaged $31,616 of income in 1989 in the United States. Someone with the average disposable income could not sustain multiple cars and a mansion, and that is still true in today’s economy. It is important to note that inflation has made costs very different today than they were in 1989, and the prices of houses, cars, and material goods were not the same as they are now. However, today’s narrative of Barbie still hints at a materialistic emphasis on money, mansion(s), and vehicle(s), thus reinforcing consumer-driven ideologies constructed by outside collective forces.

In 2010 the average income for the United States was $34,183. For an individual in the 18-to-25-year-old category, the same age group as Barbie, the average income was $31,610. The average income actually decreased by six dollars for 18-to-25-year-olds and increased $3,244 over twenty-one years. This disparate view of average income exposes the distorted expectations the Barbie narrative imposes. Leslie Mann of the Chicago Tribune notes the exorbitant cost of the Malibu mansion (Figure 3) in actual currency: “[The] 2013 Dreamhouse…hit stores Aug. 27 with a suggested price of $184.99.” However, Mann goes on to mention, “In keeping with the lighthearted spirit of Mattel’s marketing campaign, real estate website Trulia listed the beachfront property for $25 million.” This is certainly not the “every day” consumer’s house, let alone budget; rather the “every day” consumer has to choose between paying bills and buying the 2013 Dreamhouse.

Introducing Barbie…Again: Racial and Gender Assumptions of the World Collection

Since 1959 Barbie has created, molded, and influenced perceptions of fashion and gender identities. Mattel developed a toy that evolved with the trends of adolescent girls to maintain its popularity over a prolonged period. One of the early versions of Barbie is best known as having blonde hair and light eyes, appearing in the timeless “black-and-white strapless bathing suit” (D’Amato 12). However, there is another version of Barbie, an early production with brunette hair and light eyes (see Figure 4). On the one hand, this breakthrough plastic doll does promote diversity (paper to plastic, colors, and types of hair), but on the other hand, the diversification of representation of characteristics such as ethnicity took a couple of decades and fell short from the beginning.

This chapter explores how Mattel expands Barbie product demographics to include broader markets, including a multitude of ethnicities and diversification of the targeted age group. This conscious manipulation of its market demographic is represented by the types of dolls introduced by the company as Barbie’s friends or family, such as Ken, Skipper, and now the remodeled Teen Skipper. Due to Barbie’s strong hold on consumers, especially female consumers, and the product’s innovative adaptability to trends in popular culture, Barbie is often seen as a valuable icon to girls, women, men, children, and collectors. Barbie’s narrative is that of an idealized female figure crossing cultural boundaries. Because of this attempt at diversification, Barbie maintains her popularity across generations and locations.

The relaunch of Mattel’s Dolls of the World collection is being marketed through social media as part of Barbie’s modern narrative. However, the fantastical world Barbie embodies also encourages unrealistic mimicry that consumers struggle to achieve. The market targets vulnerable consumers, often young women who sometimes uncritically internalize the unattainable idealized image of perfection, seldom considering ethnicity, class, or gender skewing in the product. Focusing on the physical characteristics and narratives prescribed for the Brazil and Chile Barbie of the 2012 Dolls of the World collection, this section describes the subtle underlying stereotypes propagated by consumerism and technology implemented by Mattel.

The iconic Mattel doll presents young consumers with classic idealized female representation. However, if versions of Barbie (specifically in the Dolls of the World collection) continue to be marketed as an unrealistic ideal, what messages can consumers take away when Mattel produces prototypes embracing and reproducing harmful stereotypes through the doll and social media venues? Essentializing identity constructions proves deleterious to the populations being depicted. Stereotypes become explicitly expressed; gender and ethnic physical features become hyper-accentuated. Phenotypical characteristics dominant within American cultures are used to describe non-European American cultures, and hypersexualized feminine images become the norm for beauty.

Looking at how technology has shaped depictions and narratives of Barbie is important for both consumers and educators. If uncritical examination of Barbie goes unchecked by the general consumer, we miss opportunities for engaging communication interrupting hegemonic ideals and spaces, including online spaces. Stephanie Vie comments that even the classroom benefits from such investigation: “Reframing literacy in the light of participatory spaces like social networking sites will be the key to harnessing the potential of these sites for composition pedagogies appropriate for the 21st century” (“Digital Divide” 21). In other words, the way interactive media is collaboratively generated can be beneficial or harmful depending on how information is critiqued, formed, and shared by communities.

However, it is necessary to critically examine stereotypes and gender ideologies among proliferating Barbie images and narratives. These images are often created by media continuously profiting from uncritical awareness and responses accepted by consumers who are inadvertently shaped by and shaping digital social contexts that create spaces for passive acceptance of embedded assumptions about gender and ethnicity. Although current definitions of literacy, particularly technological literacy—a method that “connect[s] social practices, people, technology, values, and literate activity, which, in turn, are embedded in a larger cultural ecology” (qtd. in Vie 14) and categorized as one of two types: acts of literacy or metacognitive understanding of literacy (Vie 14)—continuously undergo changes, the assumption of access to technological literacy is still leading to false portrayals, meaning that although it may seem as if consumers have equal opportunities to learn about products and ways to navigate technology that better connects consumers to products, the availability of access to technology is far from equal.

Perception of equality of access, like perception of equality in representation, is based on presumed constructs of identity imposed by dominant narratives. Annette Harris Powell states:

This display of usability and access instead depicts a dynamic image of relationships coalesced with technology, both positively and negatively, and gender and/or ethnic influence opposing the either/or binary traditionally thought of in terms of the digital discourse. Representation of access to participatory sites such as Facebook used as marketing strategies or learning spaces now requires not only active reading and critical understanding of underlying motivations in the development of the image and narrative being distributed, but also a critical awareness of who has the ability to speak for communities within these participatory sites.

The strides women and minorities have made almost sixty years after the release of Barbie have resulted in an updated, technological, passive form of racism and sexism hidden by the rhetoric of “embracing multiculturalism,” thus pushing the digital divide discourse to the supposed edge of extinction and allowing Barbie to represent “every girl.” Rather than progressive images of realistic female identities (like the newly produced Lammily doll), occupations, and environments (although the evolution of gendered advertising is another discussion altogether), Mattel has used technology to evolve Barbie’s form from that of a simple paper toy to that of a global digital icon and symbol of femininity and perfection. Maureen Trudelle Schwarz, author of “Native American Barbie: The Marketing of Euro-American Desires,” notes: “As they are marketed by Mattel, Barbie dolls hold a special importance among toys that invite children to imagine themselves in the dolls’ image, ‘to transport themselves into a realm of beauty, glamour, fun, success, and conspicuous consumption’”1 (296). The imagined realm of this icon surpasses to a point the ideal fantasy world and comes to signify realistic and attainable opportunity for those owning or sharing experiences with this simulacrum of femininity. Consumers willingly engage with this hyperreality to escape into a fantastic world of exaggerated and unrealistic paradigms that is made all too real with the addition of interactive, participatory online spaces.

Although Barbie exemplifies the lifestyle of the young adult, young female adolescents remain a primary market. In “Does Barbie Make Girls Want to Be Thin? The Effect of Experimental Exposure to Images of Dolls on the Body Image of 5- to 8-Year Old Girls,” Dittmar, Ive, and Halliwell say: “99% of 3- to 10-year-olds in the United States own at least one Barbie doll” (283). They highlight how the doll’s iconography translates into profitability, explaining, “Barbie is the best-selling fashion doll in every major global market, with worldwide annual sales of about 1.5 billion dollars” (283). The popularity of this Mattel icon can affect one’s body image in positive or negative ways, they contend:

The exposure to and interaction with Barbie many consumers have affects their psychological representation of themselves. For the young (5 ½-to-6-½-year-old) consumer, exposure to the image of Barbie “significantly depresses overall body esteem2 and increases discrepancies between girls’ actual and ideal body size3 such that girls desire more extreme thinness” (Dittmar et al. 289). As age increased, overall body esteem and desire of thinness lessened. However, 5 ½-to-6-½-year-olds were more impressionable, thus coinciding with the Dittmar et al. notion of body dissatisfaction beginning at the age of 5 and making the effects of body image a pre-existing factor for older groups (284-289). The representation of the female image becomes engrained in consumers’ psyches. The expectation that one should be thin and flawless in order to represent oneself as an ideal woman is enforced by society: men, women, and children. Sadly, the physical appearance of Barbie is not the only unrealistic factor propagated by the technological innovations of Mattel.

Change of Address: Critical Analysis of Barbie and Moving Qualifications

Critical discourse analysis methodology provides an approach for looking at the assumptions coded into the images and symbols that—like Barbie—are presented as ideologically neutral. According to Thomas Huckin, critical discourse analysis is a “context-sensitive, demographic approach which takes an ethical stance on social issues with an aim on improving society [… an] approach or attitude toward [a] textual analysis” (95). In this case, Barbie, both her image and narrative, is a text; the set of social ideologies and practices being composed is based on this Mattel icon.

Even though Mattel produces Barbie with a multitude of accessories, vehicles, and occupations, the corporation also produces Barbie and relative figures with background stories that ensnare consumers with the product’s semi-realistic personal narrative. The tailor-made story provides Barbie with a façade, making her relatable yet simultaneously fantastic. Barbie is just like “every girl”, the “every” day consumer; she epitomizes the Eurocentric American idea of beauty and success. In this consumer-driven world, individuals connect to the product on a deeper psychological and emotional level because of various characteristics of the product. With the aid in social media, this personal connection becomes deeper and more subversive uncritical analysis can take place. If digital places like Facebook for Barbie are taken into account, it is safe to say that Barbie's followers have created a community. Due to reflective bonds of personal aspiration, characteristics, and memory, collaborative communication occurs and information or knowledge is shared.

Pertaining to Vie’s concerns noted earlier, this participatory site can reflect positive or negative representations of access, ethnicity, and/or gender. These participatory sites are rife with information. As David Dadurka and Stacy Pigg suggest, new developments in scholarship call for research regarding community literacy in online space. Scholars including Dadurka and Pigg are starting to acknowledge the importance of digital intersections in that such manifestations create “innovative ways of knowing, thinking, and acting that frame individuals with distributed networks of activity, rather than isolated readers, and writers” (11). This implies that contexts of learning are changing. There are now more dynamic ways of looking at sociocultural identity as who has access to create digital communities that share various knowledge(s) for different purposes continues to change in an attempt to adjust unfair representation. “Language abilities, technological abilities, and dynamics of gender, race, and class,“ say Dadurka and Pigg, ”do not disappear when community is built online” (9).

The narrative of Barbie is one reason the product has maintained popularity throughout the years. Continual investment in and recreation of her story allow individuals to escape into nostalgic or paradoxical fantasies (seen in sites discussing how to be like Barbie, fan sites, Facebook pages, and headlines in tabloids about medically altering body parts) that more or less leave the consumer to insert her into any timeline deemed necessary; Barbie is both classic and current in the scope of pop culture. The relaunch of Mattel’s Dolls of the World collection is partially entwined with the marketing of Barbie’s postmodern social media campaign narrative. Under the “Videos” tab on Barbie’s website, which is like an interactive playground for preteens, on a virtual blog for Barbie, consumers receive notice of a major change coming to Barbie’s lifestyle and the Mattel collection. Anyone keeping up with Barbie would have seen the moving boxes on her website in February 2013. This symbolic “move” aligned with Mattel’s relaunch of the Dolls of the World collection in a 2012 and 2013 campaign.

The first image on Barbie’s homepage is a picture of her in front of her Dreamhouse posing with a pink moving box labeled “Shoes.” There is a stack of pink boxes to her right. Some of the boxes are labeled “lip gloss,” “mascara,” “letters from Ken,” and “glitter” (this box is on the far right bottom corner). To her left, on the right of the screen, there is a blue quote bubble with yellow text that says, “I’m moving!” (see Figure 5).

This text bubble is depicted in blue, contrasting with the pink boxes. Blue is at the opposite end of the color spectrum, making this information the focal point of the home page. Another reason this text draws the observer’s eyes to the message is its location. This portion of the image is in the upper corner through the mid-center of the screen. The center of the screen emphasizes a link allowing viewers to watch an interview with Barbie that describes her big move (see Figure 6).

Although the entire page shows what may look like pinpoint reflections of glimmering light, this effect actually replicates the look of glitter. This “glitter” spreads throughout the entirety of the page and is illuminated at different speeds, widths, and intensities; the quote bubble and the video link have a denser cluster of illumination that sparkles at an increased rate when compared to the rest of the dispersed “glitter.”

Along with the twinkling depiction this “glitter” invokes for the observer, there is another underlying connection this technological representation of “glitter” can symbolize. The objectification of a woman, in this case a doll, by associating and highlighting her with images of “glitter” materialize Barbie, a depiction of a woman, as a shiny object or as a reflection of status. Once the observer or consumer views the image of a woman as an object, that image can be acquired, gained, and/or conquered in the mind of the objectifier (Shrage, “Feminist Perspectives on Sex Markets”). The “glitter” signifies the shiny reward at the end of a task, the trophy for Best in Show. The digital enhancement to make the doll more attractive by means of “glitter” is a way to reinforce a power hierarchy exploited by gender roles, not just to catch the consumer’s attention.

However, by emphasizing the quote and the video link, the web designers emphasize the concept of change, giving the written text prominence, depicting movement, and offering visual distinction in the foreground as opposed to the still images of Barbie and her packages. This promotes the producers' intent to sell the mansion, impose Barbie onto other cultures, and shake up the narrative of Barbie in hopes of increasing the probability that consumers will buy into this change of scenery, the embracing of a global market which will lead consumers to want to mimic Barbie’s globe-trotting lifestyle. These seemingly harmless choices for consumers are the result of technological choices acknowledged and used by Mattel to push Eurocentric-conforming idealizations of the female image.

The image and narrative portrayed by Barbie’s social media outlets are more similar to those reflecting the dominant American narrative: an upper-middle-class or wealthy (most likely white) American with at least a high school education. This image is reinforced by the interactions developing with Barbie’s participatory sites. Jeffery Grabill describes the unequal representation within online spaces, saying, “[T]he wealthy own more computers and have greater access to computer networks than the poor. Income and education[…]are significant contributors to access. Taken together, income and education form the foundation for a profile of those who fall into subordinate class position” (459). This disjointedness fuels the digital divide and can be translated into who uses, communicates between or within communities, or is represented in online spaces based on the understanding of interfaces (Grabill 463-466). The interface for Grabill is the “rhetoric of the everyday,” the analysis in which class permeates the accessibility of technology at various locales and times and with various purposes, thus making the interface a process in which one navigates from moment to moment while connected and creating an identity. Applying Grabill’s interface to Barbie’s use of social media, we see the market responding to its primary consumers, those with access by which they can connect digitally to the doll’s image and narrative. By that measure, the Dolls of the World collection is an attempt to entice in missing consumers, those that are noticed by the Divide.

However, limited representation does not inhibit marketing strategies that make online spaces aesthetically pleasing and complementary to Barbie. Foregrounding information with “glitter” also draws consumers’ attention away from what is being omitted in the background. The saturated, overabundant pink tones leave little room for other colors. This could symbolize the lack of diversity Barbie actually represents even though she is marketed as a one-size-fits-all, “every girl” type of character. This background also presupposes Barbie to be an independent female who is self-sufficient and able to live on her own. But this visual language constructs an idea about Barbie’s identity that is somewhat misleading. Discursive differences in this image lead observers to believe in the possibility of her independence, yetin further analyzing this image, one begins to wonder how successful Barbie is at being independent if she is trying to move herself while dressed in a short dress and packing boxes of “glitter,” makeup, and postage rather than clothes or furniture. The creators of this text depend on the website participants’ acceptance of the image and narrative of Barbie. Huckin notes, “Writers can exploit these discursive differences to manipulate readers in various ways” (100). By exploiting this naïvety, the creators propagate sexist stereotypes insinuating that females are not capable of carrying out work traditionally viewed as masculine such as heavy lifting or, by extension, the sustainability of independence. This stereotypical image of the “dumb blonde” is reinforced further by having the “mascara” box lying on the wrong side, implying that women such as Barbie can barely maintain the physical attributes necessary for male-dominated tasks like physical labor and should confine themselves to organization and domestic, skills.

On the other hand, critical analysis of the visual and textual discourse on this website is only part of the Barbie narrative. Once the observer gets past the home page and clicks on “Barbie Is Moving: Exclusive Randy Bravo Interview,” he or she is able to gain another level of interaction with Barbie based on the aural modality of the animated video. In the interview, Barbie discusses her attitude toward moving and the many available options. The number of choices of location she has correlates with her suggestion of knowing multiple languages, an uncommon skill, especially for those who do not travel often. Bilingual status can even be negatively associated with racial stereotypes in America, so why is Barbie’s linguistic fluency not questioned or seen as a hindrance? The simple answer is privilege. “I speak over thirty-seven languages, and I’m dying to try a few of them out,” says Barbie in her interview. This is undoubtedly connected to the countries where Mattel markets Barbie. Although transligualism is possible, speaking thirty-seven languages is neither a skill reflective of the “every day” consumer, nor one highlighted in the Dolls of the World collection. The interlocutor asks Barbie the seemingly innocent question of how she will pick the country in which she will live next. The impact of Barbie’s selecting a country in which to live in symbolizes one person’s representing an entire nation and/or culture, as if all the countries of the world plead for Barbie to be their new citizen/colonizer. She will honor them with her ideological presence. Barbie’s colonial role parallels patriarchal Anglo cultures’ and ideologies’ interrupting and appropriating indigenous cultures as if somehow endowing honors to the now marginalized people. There are multiple versions of Barbie representing America, but other countries get one and are further marginalized by being marketed in special collections or editions like the Dolls of the World collection relaunch.

The image and narrative projected by Barbie is such that she has enough money to secure the essentials for her family. She, like “every girl”, has to have “you know, the basics, a never-ending closet, transforming furniture, a glitterizer. The little touches that make a house a home” (Barbie interview). These are the basics every family thinks about when they move into a new home so as to feel safe, happy, and protected, which is after all what “every girl” in every country has, right? Who is Barbie trying to fool with her values? With a dog reading a book and a horse with an attitude in the background intentionally meaning to “de-emphasize certain contexts” (Huckin 99), consumers misunderstand the underlying assumptions needed to construct Barbie’s narrative and the marketing strategy of Mattel.

The interview places Barbie in the foreground and calls on the observer to engage with the dialogue and digest and invest in the narrative. This focuses the viewer’s attention on the center of the screen. This in turn causes the audience to listen to and be critical of the message even though the medium in which this social media marketing strategy is deployed is limited to observers and consumers whom have access to computer and the Internet and do not need the aid of closed captions for individuals with auditory or visual impairment. Amy Kimme Hea backs up this claims of the digital divide by positing, “Social media definitions often privilege the technological platform of Web 2.0 technologies [digital divide] while subordinating the users of those platforms” (1). The life Barbie broadcasts relies upon ideologically driven materialistic goods and distorted images of femininity with limited restriction, thus propagating unrealistic goals for consumers to attain in technological and hypercritical environments.

The connection between faux-human, feminine life and realistic feminine life drives the consumer’s spending and urges individuals to mimic the image and narrative of Barbie. By copying what Mattel produces for Barbie rather than having the toy accurately reflect human qualities, consumers begin mimicking unrealistic attributes. Julie Napoli and Marie Murgolo-Poore suggest, “[F]emale images portrayed in advertisements are simply a mirror of Western society’s preoccupation with the feminine ideal” (62). With Barbie’s ability to be both icon andmodel/advertisement figure, the idea of female images is being recycled with the same prototype of the leggy, skinny, blonde-haired, fair-skinned female, since the West is one powerhouse of capitalist economies. Industries are so preoccupied with recreating this façade of a perfect woman that there is limited incentive to invent or recreate cultural representations. Challengers such as the Bratz dolls have successfully carved a following of consumers with models that do not adhere to the Barbie image; the Bratz product won the People’s Choice Toy of the Year Award in 2004. Yet even with the popularity of this product, caricature and exaggeration of some physical features like eyes and lips and the intentional marketing of the hypersexual young girl (as evidenced by clothing choice) still pose problems for feminine representation (American Psychology Association). (See Figure 7).

Recent additions to the competitive market include the Bratz dolls that challenge Barbie’s strong hold on the market and the Lammily doll that allows for more accurate depictions of the “every girl” with “lammily marks” that include stickers for customizing the doll with stretch marks, tattoos, freckles, scars, bandages, bug bites, and glasses and provides some relief from the unattainable pressure Barbie imposes to achieve perfection. However, there are still some problems with female representation as explified by these dolls.

The dominating force behind Mattel exists within sexist stereotypes embedded within consumer culture leading to choices that cause the production of the dolls to remain gendered. People buy into notions of an attainable perfect female image. Embracing the far-from-plausible image of Barbie is deleterious. Nina Golgowski says:

Not only are the odds of shaping one’s image similarly to that of Mattel’s icon incredibly slim, but also if Barbie were real, the construction of her body would not be able to support her or allow it to function correctly (Golgowski). The true translation of Barbie would be a grotesque manifestation of her unrealistic narrative. Galia Slayan crafted a mock version of such an image correlating human proportions to Barbie’s features. (See Figure 8).

The image and narrative promoted to consumers, including many impressionable young women, are idealistic, Americanized images of beauty. Yet major industries, businesses, and corporations are run by men, and this creates the same binary of a masculine-dominated producing environment controlling the female-powered consumer market. Julia Dudek comments on issues of hypersexuality females face in social structures due to the pressures created by male-driven products of women in “Playing with Barbie®: The Role of Female Stereotypes in the Male-to-Female Transition” by saying, “[T]he production of ‘woman’ has been undeniably ‘fortified and sanctioned be male-centered institutions,’ which is significant in understanding the inspiration of such notions as hyperfemininity” (37). Capitalist societies emphasize creating the fictitious images of Barbie women and men continuously try to achieve or obtain instead of embracing the diversity of shapes, colors, narratives, and occupations of individuals.

This focus on gender and sexuality further drives revenue to depend on the perception of image; we are a self-conscious society that is influenced by vanity. However, that reality is not the same for “every girl”, only girls in modernized and technologically advanced societies. Karen Ross characterizes Modern Feminist in Gendered Media: Women, Men and Identity Politics as “Women’s apparent power and authority…manifest[ed] through a self-conscious celebration of their innate femininity, most obviously demonstrated through concentration on those bodily attributes which are self-evidently not male” (28). Not only are images of women created by men for women to accept and appropriate the propagated ideals of beauty, but also society as a whole is reflected in the culture of Barbie through her digital upgrade, fashion, and accessories.

Barbie and the Construction of Non-white Ethnicities

Current societal norms and ideologies are being advertised on or through Barbie. The accessories and vehicles and some of the clothes Barbie is marketed with are name-brand products. Brian Ott and Robert Mack discuss the basics about product placement: “Instead of characters in television using or wearing generic products, networks began to charge companies to promote their product by highlighting labels and name brands, or simply having characters mention a brand” (35). By framing Barbie as merely a product through which to gain profits by implementing other product placement for Mattel, the connection between females fawning over an unattainable image and the selling of image as a priority may lead to devaluation of self and viewing oneself as a product rather than an individual with one’s own narrative to construct.

Consumers may mimic the high-end fashion and designer labels that Barbie can be seen modeling, such as Bob Mackie, Stephen Burrows, and Tim Gunn; however, the limited amount of income the “everyday person” receives does not always allow for the spending of money on designer clothes. Tim Gunn might have endorsed Old Navy in early 2007 through 2010 for having trendy clothes, but I don’t think you can find him at Walmart and K-Mart. Napoli and Murgolo-Poore assert: “In more recent times researchers have shown women are increasingly portrayed as objects of sexual desire that are also attractive, thin, and young” (60). This view of women devalues their humanity and values appearance over character, leading females to be seen as items rather than people. Both men and women also uncritically accept stereotypes implicitly constructed within the narratives being marketed, specifically because the stereotypes are masked and reproduced in iconic figures held up as iconic shorthand for the ideal female.

Furthermore, the Dolls of the World collection shows stereotypes in a more pronounced manner because Mattel taxonomizes and markets these dolls by country. Each doll is produced as and meant to represent a form of female empowerment from a different country, but underneath the pricy clothes and accessories not “every” consumer can afford, Mattel is producing replicas of stereotypes communicating an ideology that privileges consumption and American ideals. Schwarz claims “[Barbies] do not convey the experience of oppression and identity structures of domination that cause it. Instead, these written accounts [product descriptions, narratives, and background stories] normalize diversity as a marketing strategy, marking differences as nothing more than fashion and consumerism” (298). The company creates portrayals of the ideal woman based on a composite of female traits or by using dominant white American characteristics to create a number of dolls of other ethnicities.

Moreover, the American description of beauty is transposed onto other cultures, thus forcing consumers to question their appearance, causing lower self-esteem and possibly a diminished sense of national pride or cultural heritage. Schwarz states: “No effort seems to have been made to develop an appropriate[…]facial type; instead, facial molds from a variety of previous ethnic and non-ethnic dolls were used[…] In actual fact, only a collector could distinguish the minute differences among the various dolls when they appear without their accoutrements” (300). To create this ideal image of a woman, Mattel produces Barbie by combining socially constructed ideals of beauty and dominant cultural assumptions about the appearance of nonwhites. How is this composite meant to accurately reflect a diverse array of notions regarding beauty? As Schwarz noted, the foundational facial construction for other countries would be barely distinguishable to the untrained eye. The look of the iconic doll ultimately symbolizes a white European-American beauty regardless of the country the plastic model is meant to represent.

The 2012 collection produced dolls representing various countries: Spain, the Philippines, France, Chile, Holland, India, Mexico, the United States (Hawaii), Japan, and Brazil. In descriptions of the Dolls of the World collection, the background narratives, body and face sculpt, and skin tone are included, revealing how ethnicity is literally constructed and erased through technological mediation. These details seem less than important in terms of how the website is designed and deployed through social media, but in actuality this information—offered in a top-down approach—illustrates a sliding scale of ethnic critique that moves from subtle racism to less subtle racism.

The Chilean Barbie, for example, is displayed as a large, close-up image that takes up approximately three-fourths of the page from left to right (see Figure 9).

This draws the consumer’s attention to the doll and focuses the eye primarily on her garb, facial features, and body structure. The other quarter of the page is dedicated to descriptions of the doll. The first set of details mentions the name (with close-up pictures of accessories) and price; the next section lists the artist and product information such as release dates and product codes. This information is given at eye level about midway through the page. After the general information has been provided, the cultural introduction follows; the Chilean Barbie begins with a greeting in Spanish (“¡Hola!”) followed by an English-language description. This arrangement of text (and limited bilingual representation) ranks physical features as the more important aspect of marketing and representation by emphasizing these characteristics first. Recognition of the designer is next, and last is the replication of the narrative, which signifies cultural diversity. The descriptive narrative, is least important; within the narrative described here, the cultural context of a character from a specific country, like Chile, is given. Portions of an identity are second, or rather tertiary, to the superficial: physical features, accessories, collectability, and the name of the designer. Although the arrangement of the text leaves something to be desired, the doll's attire also indicates whitewashed perceptions of a one-size-fits-all approach to image, markets, and representation.

The Chilean Barbie is dressed in huaso attire. However, in Chile huaso is a masculine term typically used to describe ranchers or sheepherders. The female, or huasa is not always associated with working the land. The term can also have a double meaning that can either imply that someone has wealth acquired from working land or imply that a person has less than a traditional education, carrying a suggestion of being unclean and uneducated. Furthermore, this description or use of huaso is dated and more realistically used as a symbolic allusion to the country’s past rather than as a symbol of growth and evolution. This is not seen as the typical dress of “every” citizen. This description underlies the representation of Chile according to Mattel, but this pejorative assumption is not necessarily picked up on by consumers who are paying more attention to the image that is topicalized, or placed in the forefront, (Huckin 100), than to the cultural representation from which the subject is constructed. According to “Conoce las Profesiones Más Demandadas y Mejor Pagadas del Mercado,” the leading jobs in Chile in 2010-2011 were in civil engineering and industrial engineering rather than agriculture, thus disproving the stereotypical and negative images of past Chilean contexts Mattel was presenting (PSU: El Futuro A Prueba).

Underneath the Chilean Barbie’s narrative, her body type listed as “Shani,” her skin tone is described as the “LA tan,” and her facial sculpt is mentioned as “Teen Skipper.” Consumers expect the product to reproduce features that are pleasing to them. However, reproducing images that reflect false contexts or unhealthy outlooks such as the sexualization of young girls can prove to be psychologically harmful (American Psychological Association). Similarly, the narrative here is built upon these details, constructed with American ideals in mind, representing the majority of the female Chilean population. I find it fascinating that Mattel would see Chilean females as having facial features similar those of a teenage girl and a skin tone like a tan from Los Angeles. By describing this ethnically diverse Barbie as having a tan rather than a naturally occurring darker complexion due to melanin production and as having a face like a teenager’, Mattel, Inc. imposes Western, and specifically American, ideals of beauty on other cultures and leads buyers to a faux notion of what traditional Chilean women should or do resemble. This further encourages unattainable gender- and sex-biased images and subtle derogatory stereotypes.

These stereotypes continue through South America as the Dolls of the World collection replicates a Brazilian woman. The Brazil Barbie’s narrative highlights the culture of Brazil and reinforces the festive atmosphere of Carnival through bold pops of color coupled with a homemade- and hand-sewn looking type of plain dress. This doll has accessories specific to her country that include a “cocadas plate” and a hairbrush. These accessories both symbolize and aid in shifting between Black female stereotypical images that are simultaneously attractive, good-tempered, fat, and “pass”-able.

The Brazil Barbie’s image seems to combine what Donald Bogle has identified as “the tragic Mulatto” and “the mammy” figures (9). Complicating this issue, the “mammy” figure also diverges into “militant maids” and homely “aunt Jemimas.” Brazil Barbie’s light-skinned complexion—which resonates with the tragic mulatto—is also working in tandem with the “Aunt Jemima” wardrobe combing to support Bogle’s “Bronze Barbie Doll” phenomenon. This experience occurs when Black entertainers are posed and created as an image of perfection, particularly under the white gaze. Although Bogle uses this wording in relation to the film industry, the “Bronze Barbie Doll” phenomenon can certainly be applied to actual Barbies. Bogle describes it as “not [having] one hair was out of place. Not one word was mispronounced. There was not one false blink of the eyes” (210). The quest to be accepted by mainstream America connects these images to being seen as flawless, likeable, and/or “pass”-able as a means of being accepted. The combination of light-skinned Barbie and dark-skinned stereotypical characteristics belonging to the mammy and her offspring, further emphasizes the outdated 1920s American caricatures, with grooming accessories for her perfectly placed tresses and her specialty dish that provides for the household both being imposed beauty ideologies.

The doll’s accessories and facial features reinforce ethnic stereotypes found worldwide and commonly seen in American society. The Brazil Barbie is portrayed as specifically emphasizing the “Aunt Jemima” female figure who embodies the “black cook” type of role. Stephanie Larson, author of Media & Minorities: The Politics of Race in News and Entertainment, comments on the stereotypical image of Black females in entertainment spaces falling into one of three roles, such as the “mammy,” by describing the character: “The traditional mammy was a slave or servant who worked for a white family. She was an unattractive, large, desexualized woman who lived to serve” (26). On one hand, this Brazilian Barbie attempts to embrace the Afro-Caribbean culture entwined with Brazilian heritage with “natural” hair (presumably) and a colorful sash. On the other hand, this doll reflects the caricature depictions often found throughout American pop culture as an oddly proportioned cook and female of color.

This Barbie is dramatically different to the typical American Barbie in terms of physical features because the Brazilian doll has thick, curly brown hair, a light brown skin tone, and a larger, wider nose than those dolls sculpted with the “Teen Skipper” mold. The doll’s image has the same slim body type as her white prototype, thus reinforcing the Euro-American standard of beauty. However, the dress Mattel clothes her in emphasizes her small waist while flaring out to give the doll a hoop-skirt form. This illusion simultaneously desexualizes her body to focus attention on the “cook” archetype and sexualizes her body, with attention to the waist explicitly creating the hourglass shape. The over-development of the hips and legs by way of the bell-shaped garment caricaturizes the thickness or size of the hips and thighs of Black females. The desexualizing of this doll through the disproportional and muted tone of the garb draws attention to what Larson mentions as the “mammy” or “black cook” figure. The all-white outfit reminiscent of a cook’s uniform or an apron worn by the cook only heightens this ethnically laden perception. The accessory, the “cocadas plate,” also increases the purpose of the doll to fulfill the role of the “Aunt Jemima” type of “mammy.” With a plate of food on her hip, the Brazil Barbie is seen signifying ethnic undertones of the house slave who serves the master or, in this case, the large corporation.

In a situation reminiscent of slavery in America, the house cooks and house slaves were allowed in “Massa’s” house because of their lighter skin tones, another characteristic from which the “tragic mulatto” is derived. Slaves with lighter skin had physical features, like “good hair,” that tended to give them privileges such as working in the house rather than in the fields. Geneva Smitherman highlights an important connection to Black culture in regard to hair and the kitchen.

As Smitherman posits, the term “kitchen” in Black culture is more than a location; it is a symbol of physical beauty coinciding with privilege. The Brazil Barbie is packaged with a food plate and a hairbrush symbolizing the “tragic mulatto” and the “Aunt Jemima”–type “mammy” figure that “loves to serve” commonly seen in American images. Not only does the Brazil Barbie demonstrate the quality of “good hair,” but this model also connects, perhaps inadvertently, American Black culture and Afro-Caribbean culture by imposing tensions developed from American Black cultural aesthetics to gauge standards of beauty. Put another way, the collective stereotype, which historically described lighter-skinned Black individuals, maintains appearances for the “employer” and for the self; this level of privilege manifests tensions of colorism and beauty. Having this doll reflect the light-skinned cook highlights similarities to American ethnic cultural constructs rather than the dynamic Afro-Caribbean social structures or, more broadly, international populations.

The enlarged nose and thick, curly hair are dominant characteristics that are often made caricatured and emphasized. These traits are visibly distinguishable from European-American traits. The sculpting of the Brazil Barbie is an example of this exaggeration. Only Barbie dolls of African descent are shown with this drastically different facial sculpt derived from the Mbili doll, an over-the-top, exotic African doll dressed in ostrich feathers and scantily clad in beading. However, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, individuals from Brazil are mostly categorized either as white Brazilian (Portuguese) or brown (multiracial). This difference in classification is very important because this country is primarily composed of Portuguese, French, Spanish, and/or indigenous South American people (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). Although there is a Caribbean atmosphere and Afro-Caribbean influences are seen in Brazil, Caribbean is not the primary ethnicity (2010 Population Census). The 2012 doll created to represent Brazil displays stereotypical African American4 traits rather than the variety of ethnicities in Brazil.

Though the intent may be to promote diversity by creating images of women from various cultures, the degrading standards of gender roles and pressure to attain the ideal feminine form is still prevalent in Barbie in her copious costumes. Schwarz comments on this trend:

The Dolls of the World collection not only sets and maintains trends of hyperfeminine ideologies based on masculine urges, but also promotes racialized stereotypes and imposes hite European-American views of beauty on nationalities that are not American.

The narrative of Barbie as well as the image, or rather images of Barbie in the Dolls of the World collection and the various Barbie designs are some of the reasons this product has maintained its popularity since its inception in the late 1950s. The relaunch of Mattel’s Dolls of the World collection is part of the modern extension of the Barbie narrative. However, the fictional and fantastical world of Barbie marketed by Mattel embraces and encourages an unrealistic depiction of reality, influencing what consumers imagine or perceive in terms of perfection, ethnicity, class, and gender. The physical characteristics and narratives of Barbie as well as the Brazil and Chile Barbie of the 2012 Dolls of the World collection, critically analyzed, describe the subtle underlying stereotypes propagated by consumerism and technology driven by Mattel.

Let's Get Real: Exposing My Time with Barbie

In the early 1990s, I remember playing dolls with my mom and inviting my mom’s doll to come to my “house” for dinner. My “house” was the Magical Motor Home. I did not think anything was wrong with my dolls living in a motor home. My mom had lived in a double-wide on a plot of land with a few other trailers when she was growing up, and I had friends who lived in trailer parks. What was awry was that I did not see my motor home as a trailer. I imagined it as a house, and I imagined the “everyday” occurrences happening in my motor home. Although I could not see the reality of my life transposed onto this created world, I found myself immersed in the narrative of Barbie, and that was reflected in my reality. I asked my mom to name her doll. My mom responded, “Trailer Park Tammy.” I replied, “No! That’s not right—there’s no such Barbie,” although we had clearly begun to create the narrative of the Barbie from the trailer park right there; I was just refusing to see my own narrative surpass the one Barbie had created for me. My mother, had been raised partially in a trailer home and had barely finished high school, did not use this moment to teach me about assumed negative images and connotations with regard to labeled groups and stereotypes. She did not instruct me on how to combat them; however, she suggested there were gaps, holes, when it came to identifying people like us, the “everyday” people like my family. People were underrepresented in the news, in magazines, and in my toys. Mattel did not market “Trailer Park Tammy” or “everyday” images of individuals; it used American ideologies such as a fantastical image of beauty and notions of capitalism as indicators of success to market escapes from reality.

In actuality, the “everyday” consumer may have one house and one car, or neither, rather than two cars and a mansion. My mom bought me the mobile home for my dolls to live in because the Malibu Dreamhouse was too expensive; our family could neither afford the mansion nor even pretend to give my dolls the expensive lifestyle celebrated by the doll’s marketing campaign, and I lashed out when my experience did not conform to the norm. However, I was naive. Mattel’s marketing campaign advertised this camper for Barbie to take camping trips with Ken and her sister, Skipper, whose image, like that of Barbie, has also undergone a makeover since the 1980s. It is telling that my earliest memories include developing an understanding of how the media and corporations omitted representation of or created or propagated false or stereotypical representations of individuals. Barbie did not live in a trailer. According to her narrative, Barbie only camped in one vacation vehicle away from her Dreamhouse. The standards of her fiscal type and phenotype imply that society should somehow reward her, and those like her who are born into wealth and beauty, with mansions, cars, and world travel while the “every girl” Barbie supposedly reflects manages a staycation (a vacation one takes either to explore the city one lives in or to relax while staying home), budgets to pay bills, and juggles her professional life and her personal one. Let’s get real: Where are the working-mom Barbies, the charged-with-a-crime-because-of-ethnicity-or-socioeconomic-status Barbies, the activist/community service Barbies?

Bibliography

American Psychological Association. Report of the APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. APA, 2010. Web. 30 Jan. 2015.

Ballet Barbie. Personal picture. 20 July 2015.

“Barbie Malibu Dreamhouse.” ToysRUs. Geoffry, LLC. 2014. Web. 28 Apr 2014.

Barbie. “Barbie Is Moving: Exclusive Randy Bravo Interview.” Mattel, Inc. YouTube. 2013. Web. 30 Jan. 2014.

“Barbie Facebook.” Facebook. 24 May 2014. Web. 24 May 2014.

“Barbie Fan Club.” Fanpop, Inc. Townsquare Entertainment News. Web. 24 May 2014.

Bogle, Donald. Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films. 4th ed. New York: Continuum, 2001. Print.

Boren, Cindy. “Move Over, Barbie, The Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue Is Here.” The Washington Post. 18 February 2014. Web. 24 May 2014.

Brazil Barbie, The. “The Barbie Collection.” Barbie Collector. Mattel, Inc. 2014. Web. 30 Jan 2014.

Bratz. Personal picture. 30 June 2015.

Carter, Jane. “Malibu Dreamhouse Up for Sale! Barbie Is Moving.” Morninggossip.com. 8 Feb. 2013. Web. 24 May 2014.

Chao, Ning. “What Does a Real Life Barbie Look Like?” Beautylish. Beautylish, Inc. 19 Apr. 2011. Web. 24 May 2014.

Chilean Barbie, The. “The Barbie Collection.” Barbie Collector. Mattel, Inc. 2014.Web. 30 Jan 2014.

Dadurka, David, and Stacy Pigg. “Mapping Complex Terrains: Bridging Social Media and Community Literacies.” Community Literacy Journal. 6.1 (Fall 2011-2012): 7-22. Print.

D’Amato, Jennie. Barbie All Dolled Up: Celebrating 50 Years of Barbie. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2009. Print.

Dittmar, Helga, Suzanne Ive, and Emma Halliwell. “Does Barbie Make Girls Want to Be Thin? The Effect of Experimental Exposure to Images of Dolls on the Body Image of 5- to 8-Year Old Girls.” Developmental Psychology. 42.2 (2006): 283-292. Print.

Dudek, Julia. “Playing with Barbies: The Role of Female Stereotypes in the Male-to-Female Transition.” Transgender Tapestry. 104. (2003): 295-326. Print.

Early-Model Brunette Barbie. Personal picture. 20 July 2015.

Golgowski, Nina. “Bones So Frail It Would Be Impossible to Walk and Room for Only Half a Liver: Shocking Research Reveals What Life Would Be Like if a Real Woman Had Barbie’s Body.” Mail Online. Daily Mail. 13 Apr. 2013. Web. 28 Apr 2014.

Grabill, Jeffrey. “On Divides and Interfaces: Access, Class, and Computers.” Computers and Composition. 20 (2003): 455-472. Print.

Hea, Amy C. Kimme. “Social Media in Technical Communication.” Technical Communication Quarterly. 23.1 (2014): 1-5. Web.

“How to Be Like Barbie.” WikiHow. Mediawiki. Web. 24 May 2014.

Huckin, Thomas. “Critical Discourse Analysis.” Journal of TESOL-France. (1995): 95-111. Print.

Instituto Brasilerio de Georgrafia e Estatìstica. “2010 Population Census.” Instituto Brasilerio de Georgrafia e Estatìstica. Web. 30 Jan. 2014.

“Lammily.” Lammily, LLC. MOJO. 2015. Web. 29 June 2015.

Larson, Stephanie. Media & Minorities: The Politics of Race in News and Entertainment. Lanham: Rowman &Littlefield, 2006. Print.

“Life in the Dreamhouse.” Barbie.com. Mattel, Inc. 2014. Web. 28 Apr 2014.

Mann, Leslie. “Barbie Toys with Moving, but Remodels Instead.” Chicago Tribune News. 13 Sept 2013. Web. 28 Apr 2014.

Moody, Pamela. “Things Kim Had When She Was Little.” Pinterest. Web. 28 Apr 2014.

Napoli, Julie, and Marie Murgolo-Poore. “Female Gender Image in Adolescent Magazine Advertising.” Australian Marketing Journal. 11.1 (2003): n. page. Print.

National Park Service. “Kenneth and Mamie Clark Doll – Brown v. Board of Education.” National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior. Web. 1 July 2015.

OECD.StatExtracts. “Income Distribution and Poverty: by Country.” Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Stat Technology. 2014. Web. Apr 28 2014.

Ott, Brian. and Robert Mack. Critical Media Studies: An Introduction. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. Print.

“Ouch! Human Ken Disses Human Barbie.” Extra. TTT West Coast Inc. 08 Apr. 2014. Web. 24 May. 2014.

Powell, Annette Harris. “Access(ing), Habits, Attitudes, and Engagement: Re-thinking Access as Practice.” Computers and Composition. 24 (2007): 16-35. Print.

PSU: El Futuro A Prueba. “Conoce las Profesiones Más Demandadas y Mejor Pagadas del Mercado.” Terra. Derechos Reservados Terra Networks Chile S.A. 29 Aug. 2011. Web. 14 April 2014.

Ross, Karen. Gendered Media: Women, Men, and Identity Politics. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Company, 2010. Print.

Schwarz, Maureen. “Native American Barbie: The Marketing of Euro-American Desires.” American Studies. 46.3/4 (2005): 295-326. Print.

Shrage, Laurie. “Feminist Perspectives on Sex Markets,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2012/entries/feminist-sex-markets/

Smitherman, Geneva. Talkin and Testifyin: The Language of Black America. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 1977. Print.

Tin dollhouse. Personal picture. 20 July 2015.

Vie, Stephanie. “Digital Divide 2.0: ‘Generation M’ and Online Social Networking Sites in the Composition Classroom.” Computers and Composition. 25 (2009): 9-23. Web.

Wakeman, Jessica. “7 Real-Life Human Barbie Dolls.” Celebs: Hot Celebrity Gossip, News, and Photos. The Frisky. 24 Apr. 2012. Web. 24 May 2014.

Author Bio

Alexis McGee is a Ph.D. student at the University of Texas at San Antonio. She received her associate’s degree in biology at Blinn Junior College in 2006 and transferred to Texas State University, where she graduated with her BA in English in 2012 and her MA in Rhetoric and Composition with a self-emphasis in Ethnic Rhetoric in 2014. Her thesis, Hip Hop Pedagogies: An Alternative Praxis, was nominated as a Texas State University Outstanding Master’s Thesis in 2014. Alexis currently focuses on African American language and Rhetoric, Hip Hop Rhetoric and Pedagogy, and Black Feminisms at the University of Texas at San Antonio, where she also teaches technical writing, and first year composition. Alexis is the 2014-2015 recipient of the National Council of Teachers of English Early Career Educator of Color Award.