Relational Positioning in Multilingual Thirdspaces: An Emerging Methodology

In attempting to analyze the transnational literacy narratives presented here, we have relied, in part, on Soja’s (1996) important work with thirdspaces to help us understand how Debleena, Cornelia, and Lisa position themselves in their telling as occupying in-between spaces in which they sometimes stand culturally apart from the language and place in which they abide. Reynolds (2004) has also helped us understand the significance of place in these women’s lives while Bruner (2001) has provided a foundation for understanding how memories of the past also shape the present for all three women in our study. But it has been Michael Bamberg (1997) who has given us specific questions that have also shaped our analysis. He would have researchers examine the ways in which narrators situate themselves in relation to others in their narratives as well as to their audiences. And he also suggests that researchers should look at how the narrators see themselves in relation to their own selves.

Bamberg asks, for example—“how are the characters positioned in relation to one another within the reported events?” (p. 337); “how does the speaker position him- or herself to the audience?” (p. 337); “how do narrators position themselves to themselves?” (p. 337). These are all questions we have put to use in attempting to analyze transnational literacy narratives.

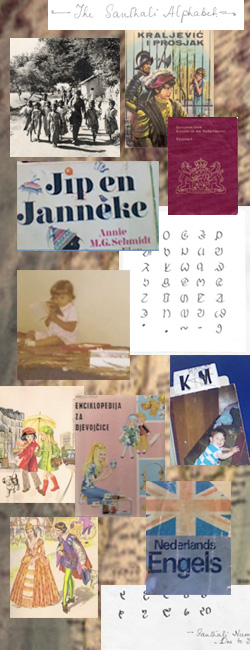

Each woman in our transnational exhibit understands herself as part of a family whose members play a significant role in her narrative. Debleena, for example, writes of her mother describing how Debleena, like Cornelia, would “as a baby” look at picture books before she could read, books Debleena and Cornelia continue to treasure. Debleena also writes of her father’s not wanting to buy a television for fear it would interfere with her literacy learning, but books, she notes, her father never denied. She also mentions her family’s speaking three languages at home with specific reference to her father’s teaching her how to count in Dutch and her learning of French in connection with her father’s French geologist colleagues as Indian languages “flowed around [her] all day.” Debleena aligns herself strongly with her father and her mother, whom she remembers “bursting into song” at the first sign of monsoons. But she also understands herself and her literacy narrative as unique: language and her own encounters with the literate world are magical. And these magical encounters lead her to set goals for herself apart from her family but which eventually aim to bring her back to India. She writes: “How shall I say that I feel I shall not be an educated Indian unless I go back and reside among my roots, after a long sojourn in foreign lands? (our emphasis) She will not consider herself educated without prolonged education in places abroad.