Literacy Narratives

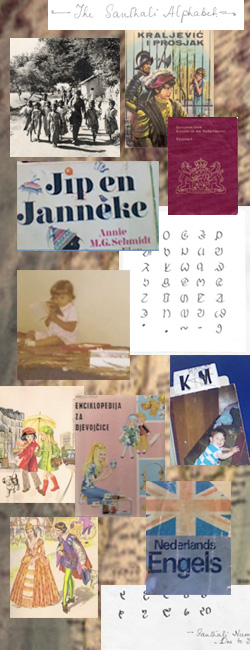

We begin with three narratives representing three different transnational experiences with literacy and language. Debleena Biswas, of Calcutta, India and now San Diego, California, centers her narrative on the Calcutta Book Fair and her experiences there as a young adult, shaped by her multilingual childhood. Cornelia Pokrzywa, of suburban Detroit, Michigan, highlights the space of the home as central to her language experiences as a child, a space filled with Croatian children’s books. Lisa Chason, now of Santa Barbara, California, stresses the importance of her children’s education to her own experiences in learning Dutch as an American living in the Netherlands. Each narrative focuses on the centrality of language and place in each woman’s literacy experiences. In these narratives, the women position themselves in what Edward Soja has named a “thirdspace,” part of a theoretical stance he sets forth to encourage readers to think differently about “space and those related concepts that compose and comprise the inherent spatiality of human life: place, location, locality, landscape, environment, home, city, region, territory, and geography” (p. 1). To his theorizing, we add the related concept of translingualism (Horner, 2010), which like Soja’s thirdspace recognizes not only that space and its functions are always changing but also that languages and their varieties are similarly fluid. At the same time, however, Horner and his colleagues argue that a translingual approach “insists on viewing language differences and fluidities as resources to be preserved, developed, and utilized” (p. 3). We understand these expanded notions of space and language as integral to the production of lived literate spaces as experienced in these women’s transnational lives.

As noted by one of the authors and her colleagues (Hawisher and Selfe, et al., 2010), transnational literacy experiences are increasingly providing a rich field for research in the study of writing and literacy. Yet Hesford and Schell (2008) argue that rhetoric and composition, in the turn to the transnational, still “institutionalizes certain forms of resistance . . . tokenizing individual writers over and above a contextual and geopolitical analysis of alternative rhetorical practices” (p. 462). We agree and hasten to add that the three selected DALN narratives do not in and of themselves represent the “transnational experience,” but they do represent three women’s transnational experiences. As the DALN collective emphasizes in its exhibit, the stories included here also challenge singular interpretations of identity and “grand- or meta-narratives that seek to tell the story of a particular people, event or situation" (Daya and Lau, 2007, p. 5). The strength of collections like the DALN lies in the ways in which they allow a multiplicity of perspectives while working to combat the tokenism Hesford and Schell (2008) describe by encouraging people to tell their own transnational narratives.