A Transnational Exhibit (continued)

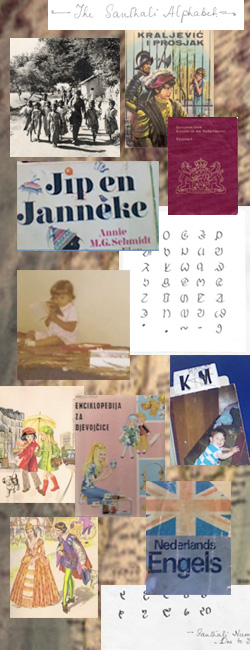

In designing our exhibit, we also thought carefully as to the best way to feature the stories of these three women. To draw connections to the prominence of place emphasized in the narratives, we first plotted their stories on a global map with links to the women's oral and written stories. This design—difficult to navigate and ultimately static—failed to emphasize the transnational movement between places that was intrinsic to the women's narratives. We then decided to select images that each writer presented and create a collage for each narrative with the hope of evoking the strong emotions each woman attached to the specific places and scenes she described. Evocative written descriptions, for example, called forth Debleena's book fair in Calcutta, India; home scenes in Cornelia's children's books from Croatia; and Lisa's everyday communication in the Netherland's Amsterdam, and they all figured prominently in the participants' memories of their transnational experiences from afar.

We also wanted these women's own words to shape the exhibit and to make their voices—whether represented in alphabetic text, audio, or video—the centerpiece of our chapter. For Debleena, we quoted extensively from her beautifully written narrative, while for Cornelia and Lisa we were able to include both their audio and video. We embedded the videos in the archive of exhibit's pages and also used audio for the quotations we featured in order to highlight their voices more prominently. Although we wanted to include more of Debleena's narrative, we were only able to link to her PDF file and her archive entry since there were no audio or video files of her descriptions for the DALN entry. Featuring the still images that she included, though, along with her lovely prose helped give a sense of her experiences with place and the people who populated the spaces she described. Seeing the photo of her walking among the children of a Santhal village juxtaposed with her written storytelling highlighted the poignancy of her narrative even without the audience being able to hear her voice.

In creating this digital exhibit, we also considered how our own interpretations could draw possible connections between these stories, and we wanted to analyze in a way that did not overpower the writers' narratives. While we featured work from these women writers in a variety of modes—text, image, audio, and video—we found that written text for us functioned most effectively as the mode through which we could try out different arguments and bring different elements of the various narratives together. Like David Bloome in writing of the whole of the collection in his foreword, however, we found a certain "unruliness" in our presentation of the narratives. As we mention above, we tried to tame a bit of the "unruliness" through revising the design into a compact and, we hope, more readable set of texts, images, and videos. But, at the same time, we confess that like Bloome we appreciate the ease with which readers and viewers can jump around through our exhibit, digitally juxtaposing videos, images, and alphabetic strings of texts in ways not easily possible through print. This ability to juxtapose, we would argue, enables a variety of interpretations for viewers as they consider the transnational literate lives of Debleena, Cornelia, and Lisa, whose narrative lives sometimes take on a touch of unruliness themselves. Through our framing sections, we hope to draw the readers' and viewers' attention to the themes of this work without restricting diverse readings and all the while encouraging new ways of considering the literacy practices of writers and composers who claim transnational connections.