Dislocation (Jackie)

Midsummer 2014. My wife is on a research trip to France, and so I am a temporary bachelor. This time of year the light comes in my window by 5 a.m., and so I am up, checking my phone for push notifications, playing slots on my iPad, brewing coffee in an old-school Mr. Coffee machine. I turn off the TV, whose noise sings me to sleep every night with Frasier and wakes me up with I Love Lucy. The remotes are poised next to the cell phone, three black rectangles against the white nightstand on my side of the bed because it takes too much effort to reach across. Next to them, dusty books I mean to finish but haven’t opened since halfway through.

A quick game of fetch with Tegan while the coffee finishes, then back to my laptop: I Skype with my wife over a nine-hour time difference, check email, see who's on Facebook, update my status, upload pictures, read my feedly.com RSS, cruise the Web, work on a Web article. I do this for a couple of hours while I drink my coffee and eat my toast, and time doesn’t pass quickly. There is boredom and the ongoing desire for something new to ping me—email, Facebook and Google+ messages, texts, phone calls. That desire pulls me further into the tech, beckoning me, orienting me toward ongoing lack and temporary fulfillment, a pas de deux with the digital that finds me lying in bed with my iPad propped on my chest, sitting at the dining room table with my laptop, standing and stuffing my phone in my pocket when I go outside with my dog. I don’t lie in bed alone, I don’t sit alone, I don’t go outside alone. I feel naked and dislocated without the digital presence next to me—what if someone calls what if someone texts what if someone comments on my post. In a discussion of Margaret Morris's Verbalucce and Mood Map technologies, the people at Intel remind me that people everywhere send 144.8 billion emails, 23.6 billion text messages, and 2.5 billion social media posts each day ("Your Computer"). I feel myself a part of this whirl. I am one (or two, or more) with the techno-universe, focusing and being focused in particular ways.

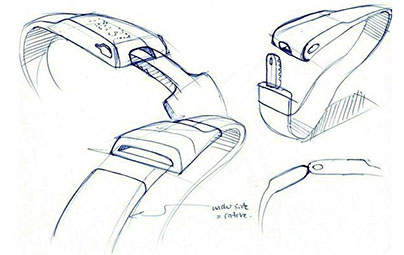

Morris and her colleagues specialize in "affective computing," creating technologies that mine body language, response times, facial expressions (in short, your body's affective moves) in order to streamline those moves, making them more efficient and socially intelligible—that is, the technologies refract and enable particular cultural values (like emotional efficiency), attuning us to the ways we "should" behave and even feel. In the course of mapping and rewarding particular movements, such technologies subtly shape us, orienting emotion and body in particular ways. Some of the technologies are overtly Pavlovian: Lumo Lift, for example, which has been stalking me on the ad feed on Facebook for the last month, will stop me from slouching by vibrating whenever my body is in the "wrong" position, i.e., probably slouched over my computer. It will make sure I "stand tall" and "feel great." And as Jonathan noted elsewhere in this piece, Maneesh Sethi's Pavlok uses electrical shocks to discipline users into good (desired) behavior.

In my embodied "coupling" with my technologies, to use Dourish's term, mean-ing, be-ing,

and other Big Concepts are constantly mediated and remediated, a dynamic process in which my technologies and I reach for (and beyond) each other. These acts of (re)mediation are embedded, or grounded quite specifically in the material, social, cultural, and historical settings in which they arise; a key part of that embedding is "a concern with the mundane aspects of social life, the taken-for-granted background of everyday action" (Dourish 96). The idea of "everyday experience" is key here. Dourish's phenomenological framework takes as its center the purposeful, active subject, mediating his or her experience through technologies. At their simplest level, technologies such as Mood Map, Verbalucce, Lumo Lift, and Pavlok offer us a reductionist stimulus–response view of behavior and cognition. Pushing against that simple view, we can see such technologies (and, importantly, our purposeful use of them) as ecologies of orientation, or complex systems that push us to act in culturally "appropriate" ways. Stand tall. Be positive. Don't waste time on Facebook. Get up earlier. Be efficient.

And so as I Skype one more time, text one more time, update status one more time, I also contemplate my everyday uses of technology. Perhaps the key is owning my own pleasure in the ongoing game of desire and fulfillment that my technologies offer me, in being more purposefully dislocated in and by them while my wife reads at the Bibliothèque Nationale nine hours away from me. For what could be more deliciously queer than the idea of desire as resistance?