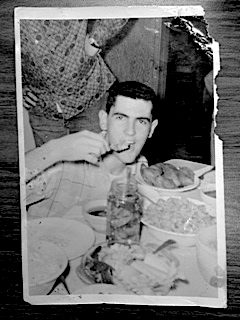

At the same time, however, Eribon is clear that such leaving is never a complete rejection of our origins, the fixed genealogies that we might want to leave behind. We might try to suppress them, but they can never be fully forgotten. As he puts it, “Our past is still there in our present. So we make ourselves, we recreate ourselves (a task that is never finished, always needing to be taken up again), but we do not make ourselves, we do not create ourselves” (223). And he’s right. As I looked at the snapshots of my uncle, much like Eribon perused photos of his father, I recognized that my uncle’s life didn’t just point in a different direction, a queer orientation; it was itself embedded in the Louisiana Cajun working class, as mine was, and that I would always live in tension with the contradictions of this inheritance:

my queerness taking me out of my family, but my periodic return to blood relations to enjoy their company; my delight in classical music and literature and my appreciation of rough-trade tough boys; my choice to live and work in urban

areas and my love of down-home, deep-fried, slow-cooked country food. I’ve called these contradictions. But they are only so in this timeline, not out of historical necessity. If anything, I’m living these contradictions. And my return “home,” while also carrying my “home” with me, is the delicious, vexed,

incommensurable meeting of contradictions: the handing to me of photographs that might want to disavow a queer genealogy but nonetheless cannot help but acknowledge it.