To add to our sense of delivery as embodied, constitutive practice, Brooke writes convincingly of delivery as performance in his Lingua Fracta. That is, he notes that our modern, commonsense understanding of “delivery” sees it as a transitive process, something that always happens with a delivered, discrete object (“delivering a pizza,” for example); he argues that “we need to think in terms of an intransitive, constitutive performance, rather than transitive or transactional delivery, when it comes to new media” (170–71). He writes:

In the case of new media, the distinction between instrument and interface . . . is even more crucial. It is debatable whether new media exist outside of performance, whether we can even speak of such media as objects in the same way that we refer to books or videotapes. A discussion list is simply a list of email addresses, for example; it is only in the performance, the consensual invocation of a discussion space, that the list exists as a medium for conversation. (181)

Brooke’s argument about delivery is a key part of his larger project—to reframe the rhetorical canons as “ecologies of practice,” part of a larger ecology of a new-media rhetoric. Ecological frameworks, he writes, offer us a way to talk about the “elaborate dance of competition, cooperation, juxtaposition, and remediation that characterizes our contemporary information and communication technologies [that] has rendered obsolete some of our most venerable models for understanding today’s rhetorical practices” (28). Ecologies, according to Brooke, “are in constant flux. Ecologies are vast, hybrid systems of intertwined elements, systems where small changes can have unforeseen consequences that ripple far beyond their immediate implications” (28). The sense of rhetoric as a “vast, hybrid” ecology helps us rethink our more static notions of the canons as discrete entities.

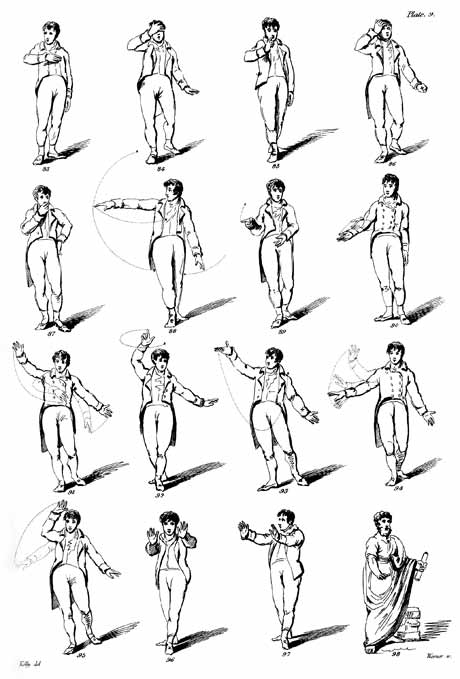

Gilbert Austin, Chironomia (1806), plate 9.