Geolocating Obama Hope:

Virtual Geosemiotics and Context Dependent Meaning

Larose Case Study

Figure 1. Photograph of Obama Hope/BP Spill mural in Larose. Julie Dermansky, 2010. Courtesy of Dermanksy.

For nearly three months after the Deep Horizon oil rig exploded, oil rushed onto the shores of the Gulf (Eliott). In the wake of this disaster, two tattoo artists in the coastal town of Larose, Louisiana began to paint murals to voice their frustration (Pitre). Bobby Pitre and Eric Guidry turned the front outside wall of their tattoo shop into their own political art gallery. A few months after the initial explosion, as the economic, social, and political repercussions continued to plague coastal communities, Pitre and Guidy painted three side-by-side murals (See Figure 1). The mural on the left features a white tower on a black backdrop. The text on the tower reads “Louisiana Water Tower.” The word water has been crossed out and replaced with the word oil in red dripping paint. On the right, a mural with a green outline of the Southeastern United States is in the background. In the foreground, a skeletal figure draped in a black robe leans their hands over the Gulf Coast and looks back at the audience. “BP” is written on the figure’s robe and the sentence “You Killed Our Gulf/Our Way of Life” is written at the top of the mural.

The middle mural is an explicit play on Shepard Fairy’s Obama Hope image. Upon first glance, it shares many similar features. The mural features the same three quarters profiled bust of President Obama as Fairey’s image. The color scheme is very similar with a wash of reds, whites and blues over Obama’s face and the background. In addition, Obama is adorned in the same blazer, shirt and tie as Fairey’s original image. There are, however, a few notable differences. First, Obama is not wearing a lapel pin with his signature campaign logo. Second, because the mural was painted by hand instead of traced, some of the face proportions are a little skewed. In this mural representation of Obama, his nose and eyes are a little bit bigger, his face is a bit leaner and longer, and his eyes darker. Third, and perhaps most striking, the word hope has been replaced with the words “what now” and 13 question marks have been painted on and around Obama’s face.

Rhetorical analysis of this design indicates how such changes helped to generate, in Guidry’s own words, “[his] own creation” (Pitre). By moving text from the bottom of the image to the top, the muralists change the textual message from the real position to the ideal position, according to Kress and van Leeuwen’s (Reading Images; Multimodality) typology. In his initial Obama Hope design, Fairey positioned the word “hope” in the real position in order to persuade voters that hope was indeed realistic for a country that he felt was experiencing a lot of negative policies under the Bush administration (“Shepard”). In Guidry’s design, hope is no longer real for the gulf coast residents that have been devastated by the BP oil spill. Instead, ideally, they want action from the federal government to help restore their way of life, a desire reflected in both the new wording and placement. This textual play on what’s real perhaps also mirrors Guidry’s feelings about Obama. “I now see our president in a different light…” he says. ”…He is not the same person I rooted for in the presidential election” (Pitre). From Guidry’s perspective, due to Obama’s insufficient response to the Gulf Coast crisis, Obama can no longer be decorated with the message of real hope. Local residents, on their own, must now figure out “What now?”

While such explanation of this mural’s purpose can be generated by rhetorical analysis, geosemiotics reminds us that the meaning of murals does not just come from their design; meaning is co-constituted by the place in which murals surface and the aggregate of other signs in which they are situated. When emplaced, murals also are co-constitutive of that place, often opening up new sites of and for politics, especially, as our research shows, when such sites are located on the periphery of nation-states. How do we learn, then, not only about the precise site in which murals surface and the aggregate of signs in which it is associated but also how an emplaced mural is constitutive of political space? When deployed as a supplement to rhetorical analysis, virtual geosemiotics can help expand potential points of analysis to disclose how once produced and emplaced, both signs and the places in which they surface often come to take on even more rhetorical and political significance (See Figure 1).

Such insight is particularly important when it comes to murals such as Obama What Now? that are highly contextual and tied to a specific locale on the periphery of a nation state. As Scollon and Scollon explain, “decontextualized semiotics makes no reference to the place in the world where the signs appear within the picture, image, or textual frame” (p. 146). Fairey’s Obama Hope image, in its original version, makes no reference to the world around it, and thus its meaning is relatively consistent across contexts. However, as we show below, the place in which the mural is painted—Pitre’s Southern Sting Tattoo Parlor—has everything to do with what meaning this mural and the parlor itself comes to take on during the 2010 Gulf oil crisis.

The Politics of Emplacement

Figure 2. Screen grab of Google Street View of Southern Sting Tattoo Parlor, Larose, Louisiana.

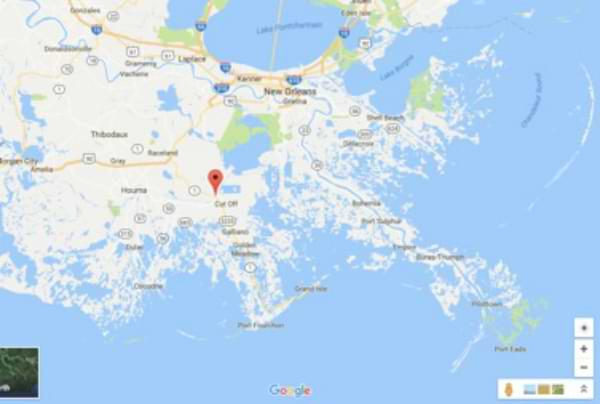

Figure 3. Screen grab of a Google Maps representation of the area surrounding Larose, LA.

Figure 4. Screen grab of Google Maps representation of the intersection of the Bayou Lafourche and Gulf Intracoastal Waterway that is located near the Southern Sting Tattoo Parlor in Larose, Louisiana.

The Southern Sting tattoo parlor is located at the corner of 6th and Main in Larose, Louisiana. Google street view allows us to explore the area more thoroughly. The shop is located just off the Bayou Lafourche, which connects to the Gulf of Mexico. At Port Fourchon, where the Bayou meets the gulf, fishing for shrimp and oysters was a thriving industry. In the immediate aftermath of the Horizon explosion, fishing was shutdown completely. Five years later, those industries had still not completely recovered (Elliot), and the Southern Sting Tattoo shop was geographically, economically and socially implicated in this local crisis.

Guidry explains,

It might not seem like any regular day tattoo artist would be affected by this oil spill, but the truth is we are being affected the same as everyone else. We depend on our shrimpers, crabbers, oyster men, oil workers and anyone else who works in these fields to make the money that supplies us a living from this art form. (Pitre)

In the face of such crisis, the tattoo parlor’s outside walls were turned into a space for political art in order to fight back against the loss of hope Guidry describes above. The Obama What Now? mural especially generates an intense encounter between the urbane President Obama and the toxicity of the oil spill. Larose sits on the end of the road to the Gulf. Emplaced in this spot, the mural marks this particular site as the end of the road for hope, an unmissable wake up call for all who live near and pass by.

In doing so, the mural certainly decries that despite the catastrophic scope of the spill, very little is being done by the federal government—a message that is only amplified by an accompanying sign declaring “BP took our arms. The Government is taking our legs. How will we stand?” (see Figure 1). But the mural moves beyond delivering a message to also reconfiguring this particular locale as an alternative space for political resistance to the nation-state. Although tattoo shops are often on a periphery of social life, they are not always explicitly alternative in relation to national and/or local politics. However, in the case of Pitre’s shop, an alternative, hypervisible political space explicitly emerged in the act of placing murals and other signs on the shop’s outside wall.

Where alternative culture was once understood as the provenance of the left, in 2010, with Barack Obama in office, alternatives started brewing from other political hues. The Tea Party, and later the alt-right, would lay claim to being counter culture movements. Although Obama What Now? cannot be directly associated with these movements, the semiotic aggregate of the mural with other Southern Sting signs skews the tattoo parlor to the political right. In the Larose video below (see Figure 5), for instance, we can see values of the far right embodied in the iconography of the Confederacy and twentieth century German militarism that surfaces in photographs of tattoos and other signs posted by the Southern Sting tattoo on Instagram. We can also see support for such values in another sign supporting Bobby Jindal, the former far right governor of Louisiana, for president—a sign that, at least for a while, stood next to the Obama What Now? mural on the tattoo parlor’s wall (see Figure 1). Made possible with public facing rhetorics such as the Obama What Now? mural and sites such as the Southern Sting parlor, the crisis of Deepwater Horizon became an opportunity to redraw a relationship with the metropolitan center, which happened to be occupied by a centrist liberal. The dialogic effect of these local signs and places amounts to a politics of the periphery that embraces and enacts anti-liberalism with the question Obama What Now? posed to arguably the United States’ greatest liberal figure by a tattoo artist who just happens to wear a German World War One battle helmet from time to time (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Video revealing the virtual geosemiotic method for the Obama What Now? mural in Larose, Louisiana. This video showcases how using virtual geosemiotics can open up potential points of analysis and deepen understanding of how place and design are co-constitutive.

Henri Lefebvre, when speaking of spatial architectonics, talks of “an intelligence of the body” (p. 174) that co-constructs geometry with the available material elements of the space that the body occupies. One might think of a spider constructing a web using different anchorage points and its own body to realize the possibilities of its own occupation. Using the spider example, spatial architectonics appears to be a concept of physics and biology, but one can extend the notion to consider social relations and politics. Indeed, to think of space in any terms other than social relations is to consider space as merely surface, a cardinal mistake for the geographer Doreen Massey. The mural, positioned as it is, not only expresses a mood or feeling, it also territorializes a relationship and leaves a gesture, trace, and mark of the political. In other words, the tattoo shop is politics on the periphery; it is a testament to bodies co-constructing their own local geometries, literally using their skin as canvas, and extending those sensibilities onto the physical material walls of Larose, Louisiana. Especially with the Obama What Now? mural, Pitre’s shop offers an answer to the question “where am I?” in which the answer exceeds the coordinates of a surface and provides an image and a site that orients the individual to the kairotic and intense politics of the Gulf.

Next SectionBack to Top