Tracking Nope:

A Critical Genre Studies Approach for New Media Rhetorics of Resistance

Case Study

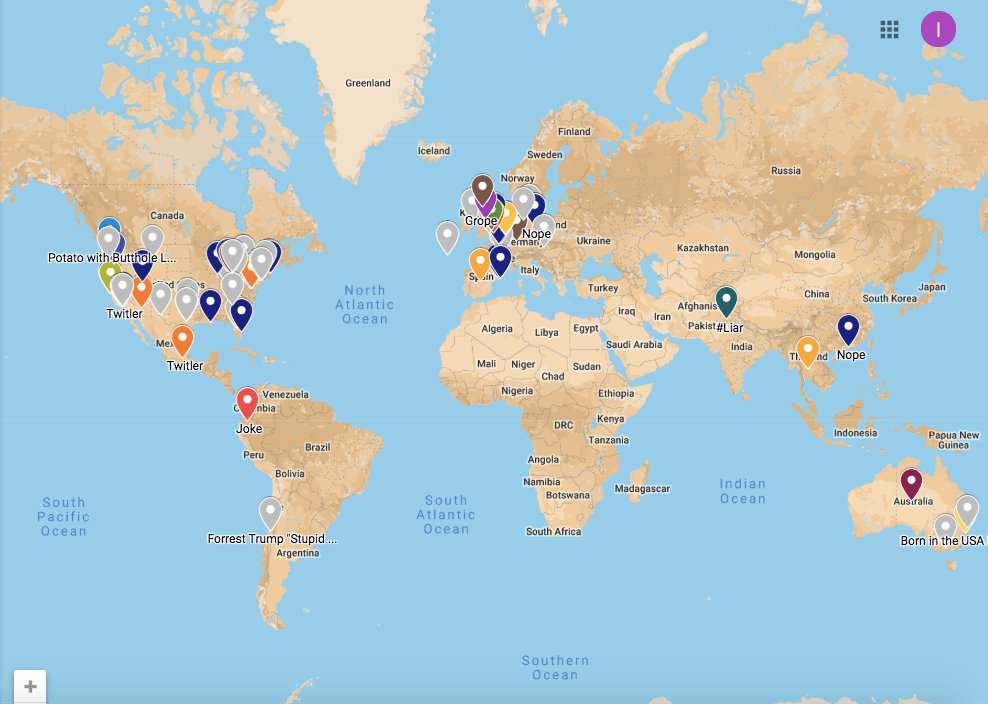

Figure 2. Still Image of Map with markers documenting 115 geographical locations in which Trumpicons have surfaced since 2011. Clicking on the map takes you to a Google Map with two interactive layers. If you click on location layer, you can access all mapped Trumpicons. Clicking on Protest layer, you can see all the different locations in which Trumpicon participated in on-the-ground protests. Clicking on all markers will put up meta-data.

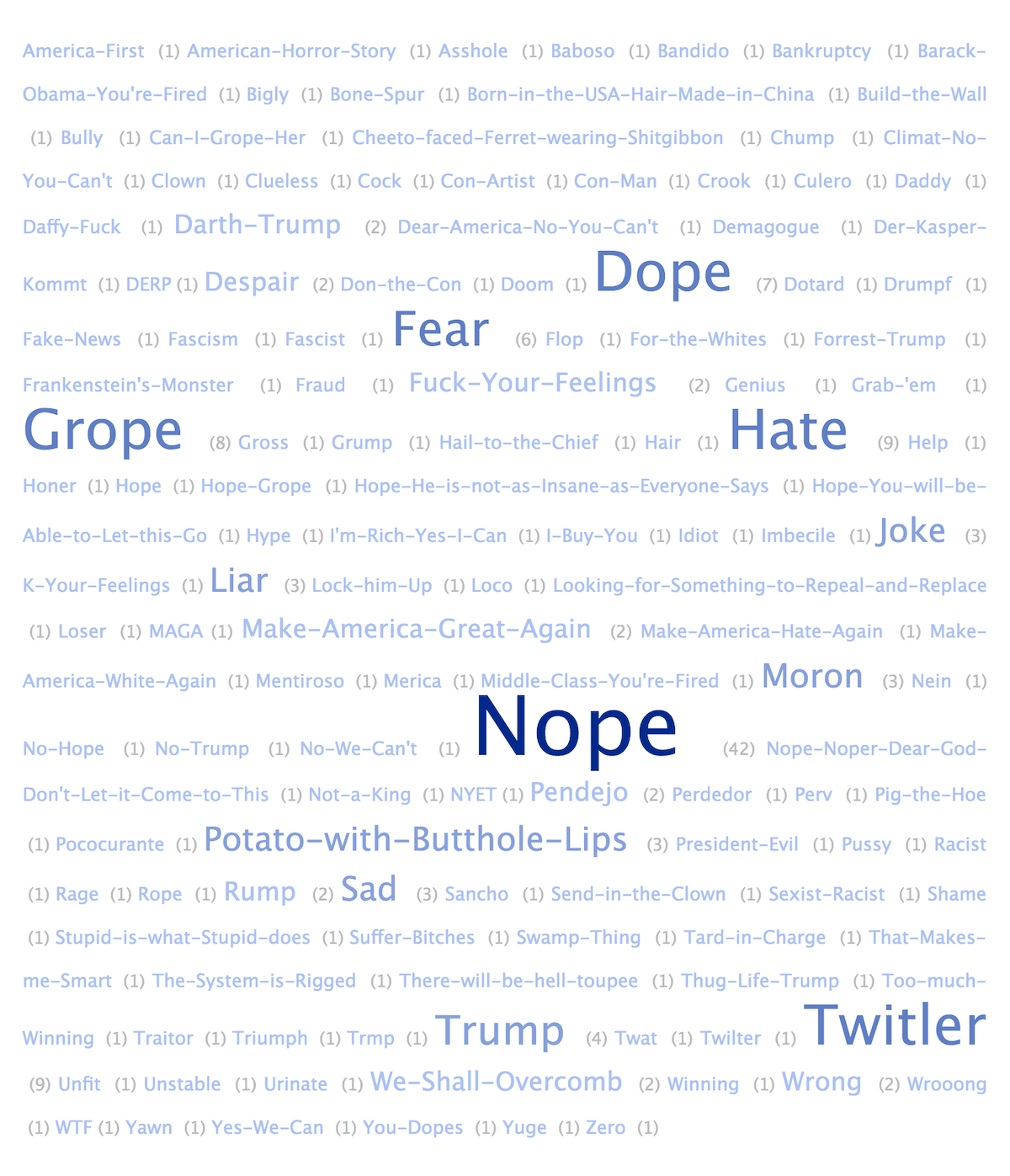

As of date, iconographic tracking enabled us to discover over 200 Trumpicons that, as Figure 2 shows, showed up across the world in digital and physical form and participated in a wide range of collective activities. Based on our content analysis of 230 Trumpicon designs, while some Trumpicons include phrases such as “Make America White Again”, most Trumpicons include a one word caption, an affective enthymeme which demonstrates that Trumpicons are reliant on speed, glance, and emotion more than deliberative argument. In terms of resistance, from “Chump” to “Clown” to “Perv,” everyday citizens have taken to Trumpicons to express their suspicions and skepticisms about his character, his behaviors, and his rhetoric and politics. Yet, according to the word cloud in Figure 3, the most prominent captions include “Nope” (42), “Twitler” (9), “Hate” (9), “Grope” (8), and “Dope” (7). In this section, we build our analysis from this and other data visualizations to focus on three of these Trumpicons: the “Hate” Trumpicon, the “Nope” Trumpicon, and the “Twitler” Trumpicon. In order to further elucidate Trumpicons’ role in the racial politics of circulation, we show how each of these Trumpicons—in design and/or social action—function to resist the white nationalist postracial logics of Trump’s rhetoric and policies, which, as Makoskvy helps us understand, contribute to white nationalism while simultaneously rejecting any kind of investment in racism, xenophobia, or white supremacy.

Figure 3. Word Cloud depicting Captions of Trumpicons from our Data Set. In this word cloud, the intensity of the blue hue and size of font communicate the frequency of captions. Darker blue and larger font represents more frequency. Additionally, this word cloud provides quantitative data, identifying the specific times a caption shows up in our data set.

Hate

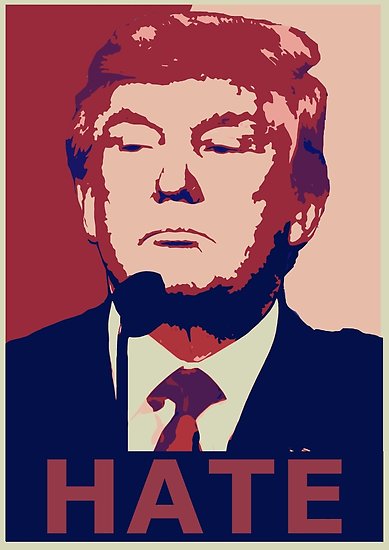

The “Hate” Trumpicon (see Figure 4) exemplifies how this new media genre often functions as a cybertype to simultaneously expose Trump’s white supremacist rhetoric and resist his racialized logics and policies. Cybertypes, we learn from Nakamura, are digital manifestations of stereotypes that circulate on the Internet to promulgate racist representations that are cemented with essentialized identities. In her work, Nakamura discloses how cybertypes are often shaped by already circulating racial and ethnic stereotypes that map onto racialized Others in the digital sphere. Cybertypes, we argue, are also shaped by self-stereotypes that people generate of themselves. As Stacey Sinclair and Jeffrey R. Huntsinger explain, “self-stereotyping occurs when individuals’ beliefs about their own characteristics correspond to common beliefs about the characteristics of a group they belong” (848). Self-stereotyping, we believe, can also occur through identification with a group that one may not have official affiliation with but does share ideological ties. As many have argued, Trump’s position, rhetoric, and policies—whether intentionally, or even consciously, or not—align with far-right ideologues, even white supremacists such as David Duke who have publicly praised Trump’s work and taken his rhetoric as clear messages to bolster their own white supremacist efforts. As Nicol Turner Lee reported for the Brookings Institution in 2017, “Under Trump, white supremacists have . . . become even more insidious as they find a comfortable ally within an administration whose last nine months has included a steady roll back of civil rights policies and promises” (n.p.). In line with how white nationalist postracial logics work, Trump, of course, has insisted that he or his administration does not condone racism or align with white supremacy. But in light of claims by Duke and others such as Andrew Anglin who calls Trump’s discourse “encouraging and refreshing,” it is hard to deny that Trump’s rhetoric has become a major part of “the engine that fuels white supremacy” in contemporary America (qtd. in Hayden).

Figure 4. "Hate" Trumpicon. Attribution: Daryl Blasi, 2016. Courtesy of Blasi.

While the “Build the Wall” and “Fuck your Feelings” Trumpicons we previously mentioned are two examples of how Trump has self-stereotyped as a white supremacist and how Trumpicons help fuel white supremacy, the “Hate” Trumpicon simultaneously calls out and resists Trump’s self-stereotyping, going so far as to mock Trump for his obvious and commonplace white supremacist, hateful beliefs. As evident in the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hate Watch and Hate Map, hate has become a common descriptor to identify far-right radical groups, many of which espouse white supremacist ideologies. According to Ahmed, such deployment of hate is not unwarranted as hate (in conjunction with love) is fundamental to white supremacy. According to their own shared narrative, as Ahmed explains, white aryans share a “love for the nation that makes the white Aryans feel hate towards others who, in ‘taking away’ the nation, are taking away their history, as well as their future” (43). In this sense, hate “works to stick or to bind the imagined subjects and the white nation together” (43). Such hate, of course, can get acted out in various ways, but at its heart, hate is both an intense emotion (49) and an affective economy that functions as a (re)organizing machine that fuels the engines of white supremacist logics, identities, and formations. Hate, like other emotions, sticks to circulating artifacts and organizes bodies with certain relations to and identifications with white supremacy.

As an act of resistance, the “Hate” Trumpicon, admittedly, could be operating in two ways: (1) expressing hate of Trump because of his stereotypical white supremacist discourse, ideologies, and political policies; (2) signifying the hate that Trump shares with other white supremacists that circulates among them and organizes their bodies, even if covertly, in shared, distributed social action. In both “Hate” Trumpicons above, the latter seems more likely, as Trump is depicted as an aggressive figure, mouth agape in the middle of a vehement scream or a fiery bellow, sending not only hate but also a warning, perhaps, to those perceived to be threats to whiteness and white ways of life. By exposing the white national postracial foundation from which Trump operates, these Trumpicons amplify Trump’s vileness—his divisive politics that leak into the public sphere and contribute to an affective economy of hate. In painting Trump as a hateful creature, these Trumpicons also warn and catalyze viewers to be on guard in the face of a president that is so malintent.

Figure 5. “Hate” Trumpicon Produced by Responsible History Education Action. Attribution: History Action, 2015. Courtesy of History Action Thailand.

Due to such rhetorical actions, “Hate” Trumpicons appear not only in protests against Trump but also efforts by activist organizations to promote human rights causes. Responsible History Education Action, based out of Thailand, as just one example, is an organization committed to not only promote holocaust education but also combat hate speech, teach tolerance, and advocate for the respect and rights for all (About). “Hate,” they pronounce in a homepage visual graphic, “is not a fashion statement.” In order to generate funds for their activist work, this organization sells their own version of a “Hate” Trumpicon (see Figure 5). In this version, Trump is not depicted as a ferocious fiend, but rather, with chin raised, a pompous, smug autocrat. While some have argued that Trump is not leading the U.S. toward autocracy or aligning with other autocrats around the world, others claim that we have not paid nearly enough attention “to the side of him that relishes autocracy and undercurrents of violence” (Dionne). While certainly different in affect from the “Hate” Trumpicon above, this “Hate” Trumpicon draws attention to such autocratic tendencies as it joins a plethora of other Trumpicons in taking action to resist the affective economy of hate that seems to be fueling and organizing figures such as Trump in white supremacist action.

Nope

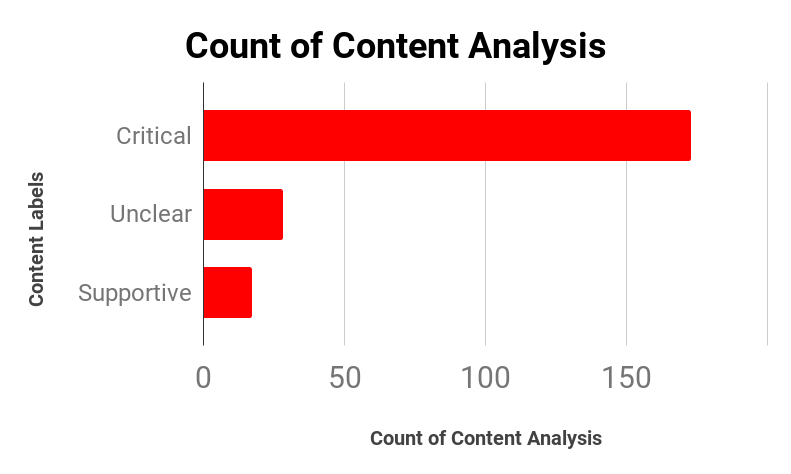

Figure 6. Interactive (tablet/desktop only) Bar Graph Depicting Results from Content Analysis of Trumpicons.

The “Hate” Trumpicon’s enactment of resistance proves to certainly not be an isolated event. The pie chart in Figure 6 indicates that according to our data set, Trumpicons are overwhelmingly critical of Trump, with only 7.8% of all Trumpicons clearly expressing support for him in design. Resistance to Trump, however, not only happens through critical designs. Our research indicates that resistance also occurs through explicit individual assertions of political opposition that accompany Trumpicons, organized protests in which Trumpicons are deployed, and commonly, according to the data, satirical parody, which often gets taken up for commodity activism. The “Nope” Trumpicon, as one example (see Figure 7), makes visible such variety of resistance, as it has surfaced in online commercial spaces, blogs, online news sources, and on-the-ground protests to enact and catalyze resistance against Trump.

Figure 7. “Nope” Trumpicon. Attribution: Unknown Designer. Posted to Imgur on February 2, 2016.

In terms of commodity activism, Trumpicons often circulate via online stores such as RedBubble and Zazzle, where people can upload designs—created by themselves or found on their Internet—and sell them as posters, t-shirts, coffee cups, magnets, cell phone covers, and so on. While surely such action can be interpreted as pure commercialism, many designers’ tags for their products, as well as explanations of design or purpose, provide evidence that their Trumpicons’ intended rhetorical action is highly political, often making direct calls to resist Trump and/or raise funds for further political action. Such participation in commodity activism is evident in the Thai activist organization example above, but as another example, two RedBubble members, who go by the name “Weneedbrain” and identify as “two queer/trans artists outraged and horrified by the Trump administration,” uploaded a “Nope” Trumpicon and posted the following in their artist notes: “Tell the world that Trump is absolutely, unequivocally #notyourpresident. *All money raised will be donated to the ACLU* to power their fight for immigrants, people of color, LGBTQ people and everyone else whose civil rights are in jeopardy.” Such enactment of commodity activism is not rare; while surely Redbubble and Zazzle are used to also express and garner political support for Trump, these commercial sites have become hotbeds for activism, as people turn to their Trumpicons to send clear, direct messages such as “Wake up…America is staring into the Abyss!”

Many of the Trumpicons involved in commodity activism, as well as individual acts of resistance on social media and in protests across the world, rely heavily on satirical parody. Satirical parody is a mode of resistance that borrows aesthetic elements from previous work and typically enacts ridicule and mockery to provoke sharp, and often humorous, critiques about contemporary figures and events in public life. As satirical parody, many might argue that Trumpicons go too far, especially in that many generate vernacular, irreverent compositions that “ignore or mock the authority or character of a person, event, or text, with the effect of offering commentary on those entities” (Dietel-McLaughlin, n.p.). The famous “Cheeto-faced, Ferret Wearing Shitgibbon” Trumpicon that surfaced on Twitter in an individual act of resistance, for instance, launches a brutal, irreverent critique of Trump’s endless attempts to create a physical and intellectual façade through his appearance and rhetoric.3 But as one Flickr artist suggests, ridicule can be a strategic form of dissent: “Ridicule forces Trump to invent reality to protect his ego. And the more times that happens, the more unhinged and unreal his fantasies will become. So keep marching, keep making funny signs, keep satirizing and joking and posting. It’s not just to make us feel better. It’s a tool, it’s protest, it’s dissent” (The Searcher). Also, we argue that irreverent Trumpicons often go to such extreme satirical measures to simultaneously reject Trump’s egregious rhetorical offenses to global citizens’ morals, ethics, and intellects and call out his facade of posing as a non-racist even as he self-stereotypes as a white supremacist—a move that is indicative of white national postracial logics.

In the perhaps less heated, yet also irreverent “Nope” Trumpicon, for instance, we see Trump depicted with wild, windblown hair (see Figure 7)—an allusion to an incident in February 2018 that created a spectacle when a gust of wind exposed the facade that Trump has a full head of hair. The “Nope” caption rejects this physical facade, which we argue also operates as a metonymy for the multiple ways in which Trump attempts to deny his stereotypical white supremacist tendencies to curb the rights of minorities, criminalize people of color, and contribute to the affective economy of hate mentioned above. This non-racist facade is also one that generates much resistance via the "Nope" Trumpicon. At a protest against Trump’s immigration ban (which we detail below), for instance, a woman holds a sign depicting the statue of liberty with a caption beneath that reads “I’m with her.” On the other side of this sign is the “Nope” Trumpicon. In its enactment alongside the U.S.’s most potent symbol of freedom and other signs at this protest stating “Build a wall against bigotry and racism,” the “Nope” Trumpicon rejects Trump’s discriminatory immigration policy while also calling out his racist and prejudicial tendencies. Such dual approach to confronting Trump’s white nationalist postracial logics and rhetorics is perhaps one reason this Trumpicon has become so broadly relied upon to not only enact but also catalyze protest both in the U.S. and across the world.

Another reason, we suspect, is this Trumpicon’s ambiguity, which takes advantage of the “Nope” Trumpicon’s ability to respond to and galvanize action against so many different rhetorical situations worthy of protest. Trump wants to ban Muslims from coming into this country. Nope! Trump wants to treat women inappropriately in public. Nope! Trump wants to perpetuate white supremacist capitalism as president. Nope! Before Trump’s inauguration, for instance, the “Nope” Trumpicon circulated in fliers generated by different organizations to catalyze resistance to Trump’s inauguration that would take place in over a dozen organized protests in San Diego alone. Take, for instance, the “San Diego United Against Hate” announcement that pairs the “Nope” Trumpicon with the following call to action:

Join Union del Barrio and the greater San Diego community as we unite on Trump’s 1st day in office!! All communities must come together to send a clear message on DAY 1! Only through organized struggle can we win – and win, we will! Actions throughout the nation will send a clear message that we will resist! We will respond! WE ARE WATCHING! People Unite! We have nothing to lose but our chains!

In this announcement, the name of the protest acknowledges the affective economy of hate discussed above, placing Trump square in the middle of it. The “Nope” Trumpicon functions to reject such hate while also protesting the inauguration suggested in the call to action. In this act of resistance, the “Nope” Trumpicon delivers an informal/vernacular rejection of not just an event, however. It also rejects our current social context at large—arguably, capitalism and white supremacy—and through such delivery, “Nope” amplifies the exigency to organize in revolutionary resistance. The call to action concludes with the famous line from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ The Communist Manifesto, which was also the closing remark in Assata Shakur’s letter To My People: “We have nothing to lose but our chains.” In deploying such allusion alongside “Nope,” the activists are able to take advantage of the ambiguity of “Nope” to identify white supremacist capitalism and evoke organized resistance against systems of domination and oppression.

Twitler

Figure 8. “Twitler” Trumpicon. Attribution: Christopher Allen Cox, 2016. Courtesy of Cox.

Like the “Nope” Trumpicon, the “Twitler” Trumpicon has become a hypervisible force of resistance in protests both in the U.S. and across the world. In this design (see Figure 8), the caption “Twitler” sits beneath a portrayal of Trump depicted as Hitler in hues of Twitter blue. As a portmanteau, “Twitler” encompasses a combination of terms: Twitter, twit, and Hitler. Undoubtedly, Twitter is Trump’s favorite communication channel—a means through which Trump can circulate his thoughts, beliefs, and theories, oftentimes with no oversight by his advisors, and provide unprecedented public access to him. Twit means a foolish, silly, and/or annoying person. Twit calls our attention to the content of Trump’s tweets which circulate innumerable outlandish and unfounded remarks that oftentimes exasperate anxieties and fears to reinforce white supremacy. Finally, in conjunction with the toothbrush mustache on Trump’s upper lip, “Twitler” connects Trump to Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, the embodiment of fascism, racism, and xenophobia.

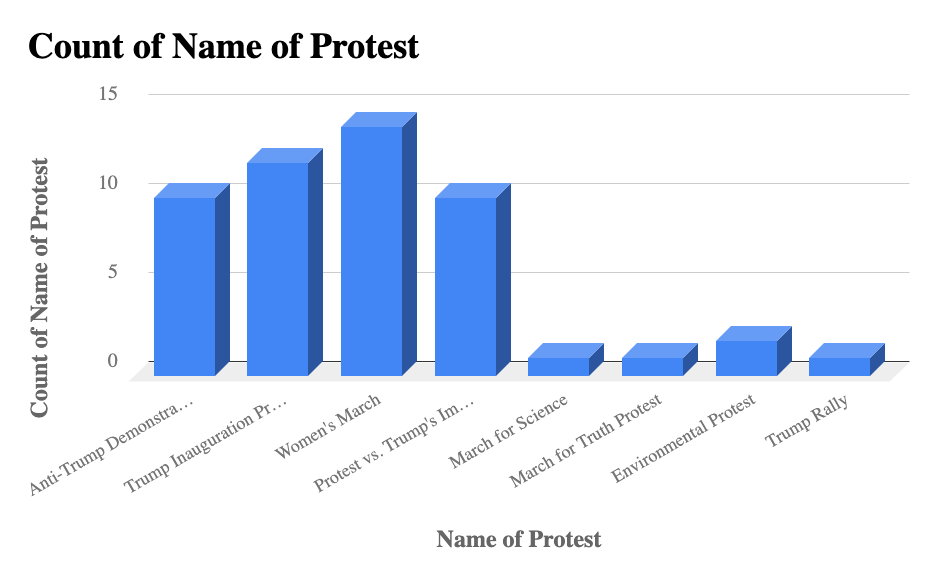

Figure 9. Interactive (tablet/desktop only) Bar Graph Identifying Types and Counts of Protests in which Trumpicons Participated in across the Globe.

As Figure 9 makes clear, Trumpicons have enacted protest in over ten different events—from Trump rallies to protests against Trump’s 2017 proposed immigration ban to protests advocating for environmentalism and people’s rights. Based on our research, the “Twitler” Trumpicon appears in nearly all of these protests: from local anti-Trump demonstrations to the 2017 March for Truth protest in the U.S. to the 2017 Women’s March that took place across the world. One protest in which “Twitler” regularly participated was the protest against Trump’s proposed immigration ban in early 2017. The ban—officially titled “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States” and often colloquially referred to as the Muslim ban—barred non-U.S. citizens from seven countries (Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen) from entering the U.S. Many have argued that such immigration policy and ban is justifiable, having little to do with xenophobia and Islamophobia. But this ban is the hallmark of white nationalist postracial discourse that attempts to reclaim white nationhood while also denying white supremacy. In their remarks about Trump’s discourse on immigration, Jayashri Srikantiah and Shirin Sinnar claim, “Even if certain remarks might be challenged as insufficiently proven or susceptible of non-racist meanings, the record as a whole cannot be read in race-neutral terms.” The “Twitler” Trumpicon goes further, suggesting in this rhetorical moment that, in fact, Trump’s rhetoric and immigration ban cannot only be read in racist terms but fascist ones. Many scholars have noted that likening Trump to Hitler is problematic. Sylvia Taschka, for example, claims that “False equivalencies . . . risk trivializing Hitler and the horrors he unleashed.” Taschka argues, “They also prevent people from engaging with the actual issues at hand – ones that urgently require our attention: immigration reform, rampant xenophobia, social and economic restructuring in a globalized world, and a loss of faith in government’s ability to solve pressing problems.” While we respect Taschka’s first concern, in its interaction with other signs and bodies at the Philadelphia airport (See Figure 10), the “Twitler” Trumpicon demonstrates that analogies between Trump and Hitler can help draw attention to contemporary exigent issues, as it explicitly calls out the xenophobic and racist ideologies undergirding Trump’s ban.

Figure 10. “Twitler” Trumpicon Participating in Philadelphia International Airport Protest against President Donald Trump's Executive Order Banning Muslim Immigration. Attribution: Getty Images News/ Jessica Kourkounis, January 29, 2017.

As Trumpicons enter into conversation with other signs at such protests, Trumpicons engage in a phenomenon that Ronald Scollon and Suzie Wong Scollon refer to as interdiscursive dialogicality in which “several discourses are co-existing simultaneously in a particular semiotic aggregate but none of the discourse’s internal meanings are altered by the presence of another” (193). In this situation, the signs are operating independently, but they are also entering into a dialogic relation so that each sign’s meaning is also building off the others (193).

Figure 11. Depiction of “Twitler” Trumpicon Interacting with other Signs at the Women’s March in January 2017. Attribution: Hillary Marren, 2017. Courtesy of Marren.

So, as in another instance, Figure 11 shows the “Twitler” sign at a Women’s March protest in January 2017 entering into a dialogic relation with a pink hat, a visual statement which became a global sign of solidarity in this widespread global protest. One pink hat knitter, who identifies with the Pussyhat Project, explains that the pink hat was “chosen in part as a protest against vulgar comments Donald Trump made about the freedom he felt to grab women’s genitals, to de-stigmatize the word ‘pussy’ and transform it into one of empowerment.” When the “Twitler” Trumpicon comes into dialogic conversation with the pink hat at a Women’s march, it works in overlapping ways to demonstrate how activists are not only protesting Trump’s misogyny but also his racism and xenophobia. Through such interdiscursive dialogicality, affects and doxa circulate among signs and bodies involved in protest, co-constituting an affective economy of resistance in which anger, frustration, and disappointment intertwine with anti-white supremacist and anti-sexist beliefs to resist Trump’s discourse and policies. Therefore, if Trumpicons like “Twitler” seem out of place to some at the Women’s March, it all of a sudden becomes crystal clear as to why activists who feel (and are) discriminated against and oppressed would turn to Trumpicons. They remind us something very important about Trump’s rhetoric and policies—that we cannot forget about Trump’s xenophobic and racist policies in a moment of protesting Trump’s misogyny—that we must, as many (queer) women of color have emphasized for decades, fight against multiple systems of oppression at once.

3. The “Cheeto-faced, Ferret Wearing Shitgibbon” caption, for instance, was first deployed in a tweet by a British man responding to a tweet Trump had made about Scotland’s vote to take their country back—an intellectual affront to anyone who keeps up with European politics.↩