Digging Up Obama Hope:

Recovering Digital Infrastructure with Media Archeology

By Blake Hallinan

“The domain obamicon.me is for sale. To purchase, call Afternic.com at +1 781-373-6847 or 855-201-2286. Click here for more details.”

Registering a domain name is a mundane affair. If you click for more details on the Obamicon.me site, you will be re-directed to form where you can enter your personal information, prove you are not a robot, and get a price quote for the domain within 24 hours. You will not find anything about the history of what used to be available at Obamicon.me, a once-active website that Laurie Gries argues was largely responsible for the mass production Obama Hope remixes that began to widely circulate in 2009 (Still Life). It is unsurprising that Obamicon.me is now defunct—with the average lifespan of a website estimated around 100 days, a lot of content goes offline (Lepore). Web users encounter this phenomena in the form of broken links (often marked with error messages or solicitations to purchase such as the offer above), automatic redirects to a different website (which is what would have happened if you had attempted to access the Obamicon.me URL back in 2016), or new content written over the old (what would happen if you purchased the domain and created your own website). In the face of such instability, often termed reference rot or link rot, you must look elsewhere to understand what Obamicon.me was and what happened to it.

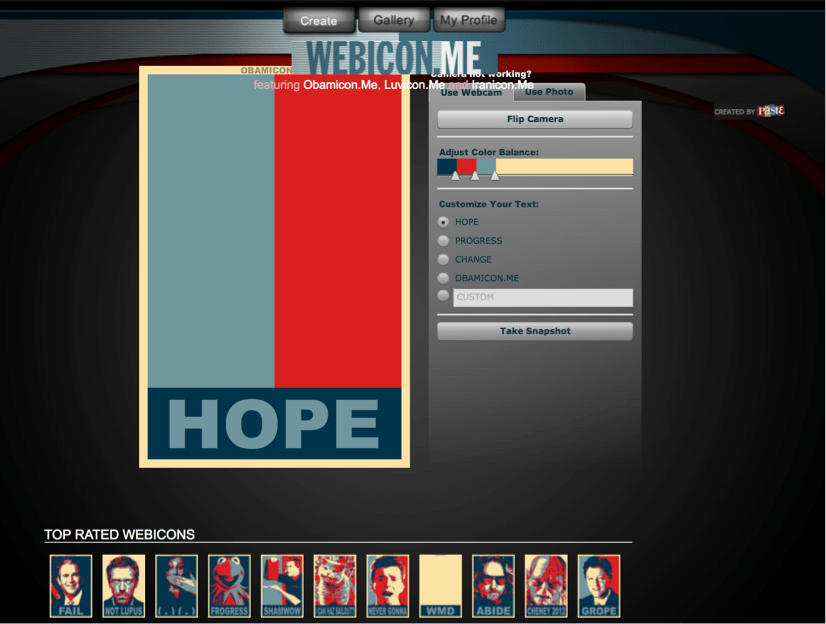

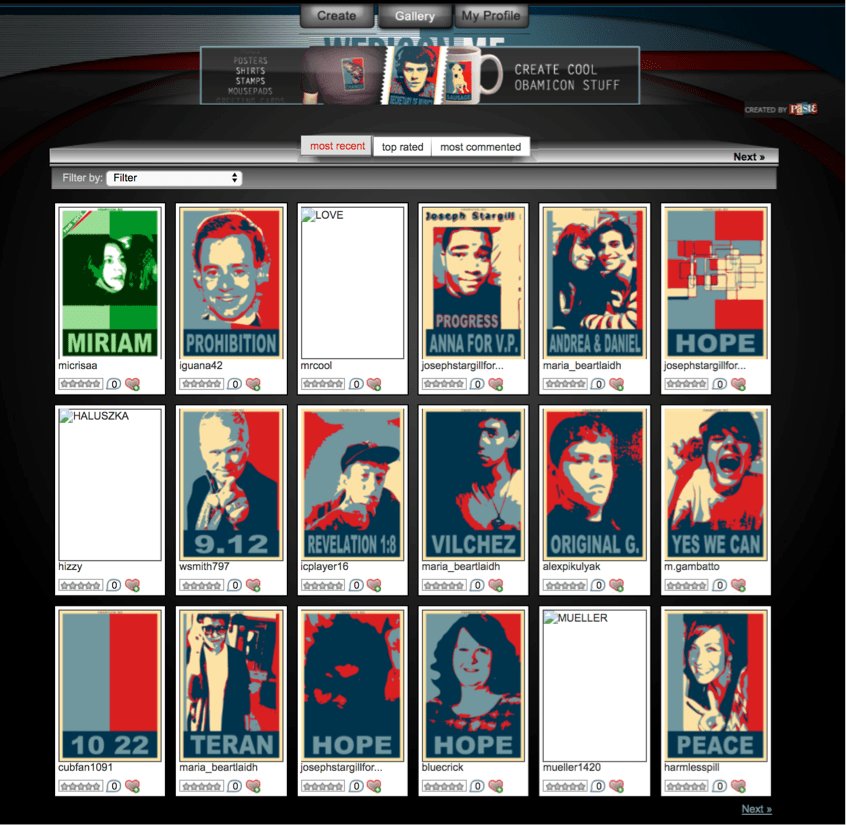

Paste Magazine conceived of Obamicon.me in late 2008, a few months before the United States presidential election (Paste Staff, “The Return”), and launched the site on January 7, 2009 with the message “Regardless of your candidate of choice in the 2008 election, here's your chance to sound-off" (Paste Staff, “Paste Launches”). The site allowed visitors to create and share customized Obamicons, images designed in the vectorized style of Shepard Fairey’s Obama Hope poster. To create an Obamicon, visitors would upload a photo or use their webcam to take one, adjust the color levels, and insert a custom caption at the bottom of their digital design (see Fig. 1). Once complete, visitors would have the option to save their Obamicon to their computer, share it directly through social network sites such as Facebook or Twitter, or upload it to the gallery on the site where other visitors could interact with the image by rating it on a scale of one to five or leaving a comment (see Fig. 2). Paste also partnered with online vendor Zazzle to offer visitors the ability to print their custom Obamicons on items ranging from T-shirts to coffee mugs (Duffy; Paste Staff, “The Return”).

Figure 1. The Obamicon generator where visitors can transform any image into the Obamicon style, replete with the limited color scheme and brief caption.

Figure 2. The Webicon.Me gallery, featuring the webicons created by visitors to the site. Visitors can also view, like, rate, and comment on webicons of others.

And people did. Within a week, the site had generated over 1.5 million views and 40,000 Obamicons, drawing in higher traffic than the monthly average for Paste’s primary website. Paste editor Josh Jackson explained that Obamicon.me “was officially bigger than our magazine site” and the image generator was part of the magazine’s successful business strategy of “generating buzz and traffic for a small, 180,000-cicrc1 [sic] magazine in a tough independent music market” (FOLIO). As part of this business strategy, the bottom of the Obamicon.me site featured a banner advertisement with an invitation to learn more about Paste Magazine, along with a trial subscription offer. Paste also partnered with online vendor Zazzle to offer visitors the ability to print their custom Obamicons on items ranging from T-shirts to coffee mugs (Duffy; Paste Staff, “The Return of Obaicon: Create Your Own Image”). To promote the Obamicon.me service, Paste launched a designated Facebook Page on 18 January 2009. Judging from the engagement levels on the oldest public posts, along with the low number of Likes and Follows on the page, few initially listened (@ObamiconMe). Similarly, a company Twitter account shared news coverage of the service and relevant announcements, such as upgrades to the site’s server in response to heavy traffic leading up to the presidential inauguration (@ObamiconMe). Such traffic resulted in the eventual creation of millions of Obamicons.

With site traffic peaking around the time of the inauguration, it is clear that part of Obamicon.me’s appeal was tied up with politics and current events. However, even that appeal is not so straightforward. Despite the name of Obamicons, Paste framed the purpose of the site around self-expression and creativity rather than political messaging—a frame that echoed in the media coverage of the viral phenomenon of remixed Obama Hope images. For example, online news sites and blogs that featured galleries of Obamicons typically selected images for humor or aesthetic qualities rather than political commentary (e.g., Marino; The Telegraph; Yoo). These featured Obamicons tended to draw upon figures from popular culture, such as Yoda from Star Wars and David Bowie, or Internet staples, such as Rick Astley and cats.2 Amidst the dominance of popular culture and internet references, political themes did appear, including variations of Obama’s image and the message of hope, such as the zombie Obama (Gries, "Obama Zombies"), and the satirization of popular U.S. political figures, such as John McCain, Sarah Palin, and Bill Clinton. People also used the Obamicon generator to modify photos of themselves, their friends, family, and pets (Mackey; Gries, "Obama Zombies"). Whether used as a venue for creativity or a good way to waste time, as a tool for political expression or provoking a small chuckle, Obamicon.me offered an ambivalent outlet. To the question posted on the official Facebook page—“Can I like Obamicons and dislike Obama?”—the answer seems to have been a resounding yes.

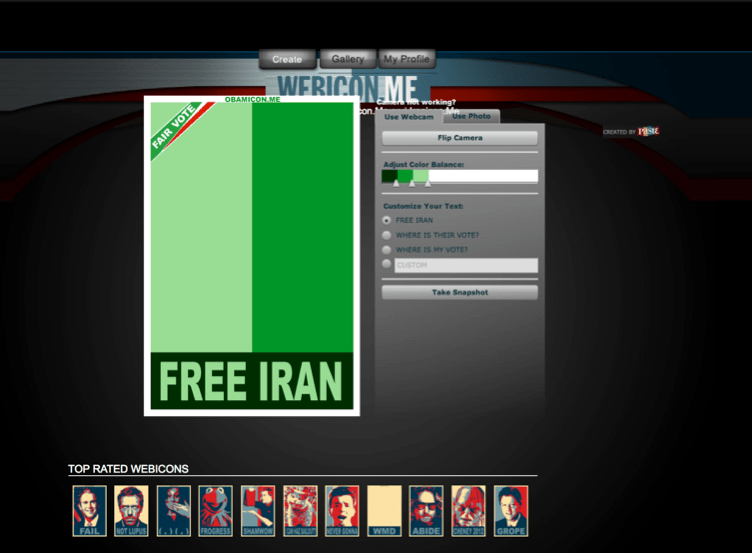

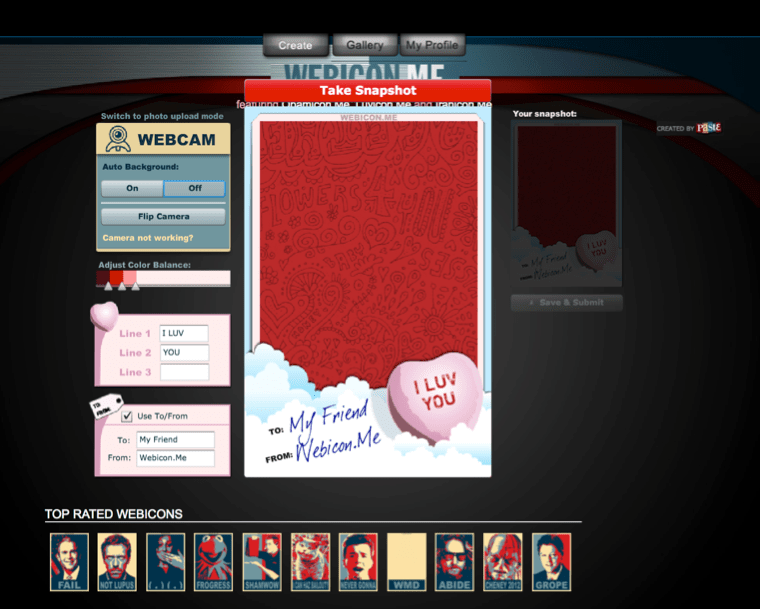

After the inauguration, the site continued to evolve both in form and offerings. Some of the changes involved making the image generators, in Obamicon.Me creator and Paste co-founder Tim Regan-Porter’s words, “white-labeled for clients” (Regan-Porter). To white-label a product or service is to rebrand it so as to seem like a creation of the client company. Such white-labeling included the Green for All image generator, designed for the non-profit of the same name, and a sports image generator for the Atlanta Hawks NBA team. Others changes to the image generator attempted to make Obamicon.me relevant to emerging events, such as the Iranicon (see Fig. 3) launched “to show support for democracy in Iran” and the Luvicon (see Fig. 4) designed to tap into Valentines Day celebrations (@obamiconme). From the end of January 2009 through September of the same year, Paste’s Twitter account featured a webicon of the day to promote the site. Shortly thereafter, Paste’s Facebook Page and primary website stopped offering updates until the announcement of the site’s return in August 2012, just in time for the next election cycle (@ObamiconMe; Paste Staff, “The Return”). Despite the initial popularity of the site, as alternative image generators and filters became available on mobile applications like Instagram, Snapchat, and Meitu, or directly integrated into social networks sites such as Facebook, interest in Obamicon.me waned. The declining interest lead Paste to take the site offline in 2013—the same year technology journalist Lauren Orsini declared “the year of the image,” in reference to the growing popularity of image-oriented social media sites such as Pinterest, Instagram and Tumblr (Orsini). From 2013 through 2016, the URL continued to redirect visitors to Paste Magazine’s main website, and by 2017, the domain was listed as available for purchase. As one Facebook user commented, “Sadly its [sic] not working anymore .”

Figure 3. The Iranicon creator, promoted as a way to show support for democracy in Iran, featuring a green stylization and short caption, along with the text fair vote written in the upper left corner.

Figure 4. The Luvicon creator offered an easy way to creator electronic valentines and featured a pink and red color scheme.

I share this story because Obamicon.me raises significant research dilemmas for scholars working at the intersection of visual studies and Internet studies, and for scholars interested in the history and preservation of visual culture. If sites that are responsible for producing, storing, and circulating digitally-born artifacts that make a lasting impact on culture(s) disappear, scholars lose important primary sources that document an image’s historicity. In the case of Obama Hope, although Obamicon.me has been taken down, traces of the site remain scattered—from files saved on computer hard drives to photos uploaded to other social media sites, from custom-printed Zazzle goods to blog and news coverage, from web forums to digital archives produced on Pinterest and personal websites. Despite these traces, the loss of access to Obamicon.me has resulted in the loss of what Laurie Gries estimates to be hundreds of Obamicons and related webicons that play an important role in Obama Hope’s rhetorical history (Gries, Still Life). For something with as much interest and uptake as Obama Hope, for something that has become so deeply embedded in the cultural psyche of our contemporary era, the immediate and complete takedown of the Obamicon.me domain marks a significant cultural void, especially for scholars of visual rhetoric. Since visual rhetoric aims to account “systematically for the ways in which images become inventional resources in the public sphere,” link rot poses a particularly pernicious problem (Finnegan).

Fortunately, digital research approaches and technologies exist that can help address this dilemma, which is the focus of this chapter. Underlying this dilemma is a concern with the infrastructure that makes possible not only Obamicon.me, but also the entire visual web. To attend to infrastructure is to examine a set of prior conditions or structuring relationships that influence an image’s unfolding and materialization. Media archeology is a particularly useful research approach for foregrounding infrastructure, especially the conditions that make the reproduction and circulation of images possible. Drawing from a German Media Studies tradition, media archeology is an interdisciplinary approach to the study of media that brackets content as epiphenomenonal in order to look backwards to the conditions that make the creation and circulation of content possible.3 Media archeology is especially useful for recovering sites such as Obamicon.me and associated cultural practices because it treats signs of decay, failure, or absence as generative and offers strategies for analyzing the social and technical structures that facilitate historical phenomena. The now-defunct Obamaicon.me site is a case perfectly consistent with media archeology’s general preference for failure, error, and stasis. Indeed, the removal of the site offers an instance of infrastructural inversion (Bowker and Star), an accident or breakdown that suddenly makes infrastructure a visible and pressing concern.

Due to its ability to draw out the infrastructure of the visual web and complicate our understanding of the materiality and temporality of visual culture generally, this chapter argues that media archeology can be a valuable methodology for digital visual studies. This chapter will begin by providing an overview of media archeology, identifying its benefits for digital visual studies, and zooming in on the method of infrastructural inversion. Next, the chapter analyzes the now-defunct image generator and social network site Obamicon.me as an instance of infrastructure inversion, drawing on records of the site available through the Wayback Machine, the public-facing portal of the Internet Archive. In addition to offering useful method for recovering visual history, this analysis also demonstrates the importance of older institutions and centralized forms of power for the circulation of images online, along with the emergence of new institutions such as the Internet Archive and their relevance for the study of digital visual culture. Finally, the chapter concludes by suggesting other ways of using media archeology to expand digital visual studies.

1. Industry abbreviation for circulation.↩

2. The turn to popular culture is also evident in other archives of Obama Hope images, such as the #obamicon collection on art community site DeviantArt, although there, the references tend towards video games and anime (“Explore #obamicon”).↩

3. In this, media archeology has similarities with Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network Theory and other new materialist approaches to thinking about the role of things. However, media archeology need not share the ontological commitments of those approaches in full. As John Durham Peters explains, "Bruno Latour, to whom I owe a lot, has polemically called for a “flat ontology,” but in the works of some of his acolytes that can sound like a refusal to make critical judgments about the great inequality of things. Anyone interested in infrastructure, lookouts, and turning points needs old-fashioned sociology about how recalcitrant, not just how cool, “things” are. Ontology is not flat; it is wrinkly, cloudy, and bunched" (30). ↩