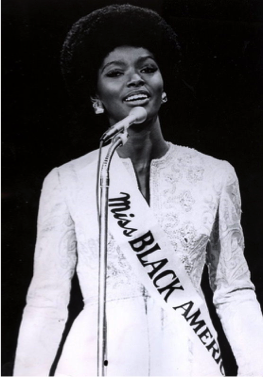

The racist and xenophobic social media that centered on Nina Davuluri winning the crown for Miss America should not be surprising. The truth is, the U.S. is far from being antiracist. In fact, the more vehemently people deny that racism does exist or claim they do not “see” race (professing a color-blind perspective), the more race and racism remain accepted norms that society fails to denormalize on a massive scale (Bonilla-Silva 73).

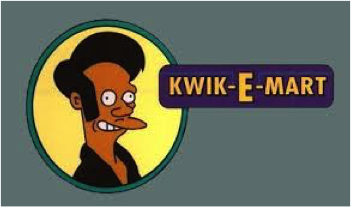

In an effort to understand how racism is produced in today’s society, I suggest that we examine the sociopolitical context in which we live. Such an examination shows that the racial status quo is maintained not only through acts of individual racism, but also through institutional and discursive forms of racism (Pimentel 52). Indeed, the racial stereotyping and profiling that emerged when Nina Davuluri won the Miss America title is rooted in the same racialized concepts that are circulated in schools and the media. Despite Indian Americans’ incredible achievements and contributions to U.S. society, they are largely absent from the school curricula and mass media, including textbooks, literature, advertisement, movies, and television shows. In mass media where Indian Americans do appear, they are usually grossly misrepresented, such as in the case of Indian American character Apu Nahasapeemapetilon on The Simpsons. This character's speech is based on an exaggerated second-language (L2) accent (Lippi-Greene 46), and he is voiced by a white, monolingual, English-speaking male, Hank Azaria. Apu’s character also works in a stereotyped convenience store: Kwik-E-Mart. As a result of limited Indian American representation through characters like Apu, we see comments in social media that replicate this narrow depiction, such as comments on Twitter in response to Nina Davuluri’s win like “Miss America? You mean Miss 7-11” or “Miss America is brought to by their sponsors PF Changs and 7-11.”

From the above reference to PF Chang’s (a Chinese restaurant) as well as the many comments that variously referred to Nina Davuluri as Arab, Muslim, a terrorist, and a member of Al Qaeda, and made references to the incidents from 9/11, it is clear that there is no distinction made by the commenters among Asian countries such as China, Saudi Arabia, and India or understanding of the fact that the Middle East includes parts of the continents of Europe and Africa. The tweets that misconstrue Nina Davuluri’s nationality, the blurring of various countries, and the failure to recognize the ethnic, racial, religious, and linguistic diversity within specific countries indicates the lack of awareness of and education that focuses on these issues. India alone contains twenty-eight states in seven different union territories and contains speakers of over two hundred languages and dialects and people whose religions include Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism, Jainism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism. Indian Americans in the U.S. also have very diverse experiences.

Yet the dominant singular ideas of who Asian or Middle Eastern people are, as well as the lack of distinction between the countries and people in these massive geographic areas, is not surprising given the limited exposure U.S. Americans have to such diversity. Film expert Jack Shaheen examines more than one thousand Hollywood movies and found that Arabs were rarely portrayed as anything more than heartless terrorists. Included in his analysis was the animated movie Aladdin, wherein Arab characters signify all that is villainous. Moreover, the Aladdin narrative carelessly substitutes Indian characters and references for Arab people (see the YouTube analysis of Aladdin for more details). The depiction of Arab people (Indian people are often included) as villains has profound effects in reinforcing the racialization of the society in which we live. Nigerian fiction writer Chimamanda Adichie eloquently addresses “The Danger of a Single Story” in representing the diverse lived experiences of national groups. In her provocative speech, she gives vivid examples of how people often rely on “single stories” to understand both local and distant others. She discusses how she has naively relied on these “single stories” to understand the experiences of others and how others often rely on these “single stories” as they imagine what it is like to be African.

No doubt a single story has been circulated about Indian Americans, and this resulted in the racist discourses that targeted Nina Davuluri. Even though Davuluri was able to maintain a positive attitude and thrive in her role as Miss America despite the racially hostile environment in which she won, other Indian Americans face relentless discrimination in school and at work. As Gibson’s ethnographic research on Indian American high school students revealed, the Indian American students she spoke with all experienced verbal and physical assaults regularly:

Clearly, the racial profiling and abuse Indian Americans face needs to be addressed. In the following section, I highlight how racism can be addressed in the college classroom through digital media.

Using Digital Media to Address Race in the College Classroom

Racism no doubt impacts students’ college classroom experiences (Kynard 2; Martinez 34; Pimentel, Pimentel, and Dean, in press) as well as university professors’ experiences (Kynard 6). While university professors, including writing professors, have been called upon to diversify their curricular and pedagogical approaches, race scholars have noted that these changes often are superficial and do little to impact social justice. Pimentel (97), for example, states that composition instructors tend to play it safe in their moves to make their classes multicultural, perhaps by adopting multicultural readers as part of their reading lists. Such “safe” attempts to implement diversity in the writing classroom do very little to bring about “the pedagogical changes that are necessary to identify the ways in which students’ cultural knowledge and language practices can be expressed in their writing” (Pimentel 97). Similarly, Kynard (2) points out that while many white students and professors researched people of color, racism persists in college and university settings. Further, Kynard states, “While much of our work that has chronicled the multiple literate lives of students of color has been embraced, it is not clear that the work has actually been mobilized to change classrooms for students of color in schools and colleges” (2).

This chapter suggests that digital media can be used as a means of taking up and addressing racial issues in the writing classroom. Students can do work similar to the racial analysis in this chapter to examine racist incidents as well as the racial commentary that emerges in social media and Internet news sites. Nakagawa and Arzubiaga (108) identify social media as a “laboratory” of racial discourse students can analyze in an effort to develop racial literacy. Focusing on YouTube, Nakagawa and Arzubiaga demonstrate how students can perform a critical discourse analysis (CDA) on the abundance of racial data that appears in original content, responses, and comments on YouTube pages. While Nakagawa and Arzubiaga‘s article highlights the “Asians in the Library” video, wherein a white college student complains about the number of Asian students on the UCLA campus, there is a continuous stream of racist YouTube videos, responses, and comments students can analyze. Just some of the racialized topics students can investigate in YouTube videos as well as other social media sites are racial profiling, police brutality, immigration and the U.S./Mexico border, bilingual education, ethnic studies bans, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) students, segregation, and the educational achievement gap.

As students examine the racial narratives they encounter on social media sites, they can apply critical media literacy (Share) as a framework for critically analyzing other texts. Critical medial literacy (CML) is an approach to literacy that transforms students from passive consumers of texts to active negotiators who deconstruct and challenge the ideological messages communicated through all sorts of media. In a broad sense, CML “brings an understanding of ideology, power, and domination that challenges relativist and apolitical notions of media education in order to guide teachers and students in their explorations of how power and information are always linked” (Share 14). By applying a CML approach in the classroom, students can interrogate media by asking critical questions of the narratives they scrutinize, some of which include: Whose perspective is represented? Who is featured as the most prominent person in the narrative? Who and what details are omitted? Who is the hero of the story? Who has agency? How are problems solved? and Who is the antagonist? Answers to these questions often shed light on the underlying white supremacist discourses that populate dominant forms of media. Once students recognize these discourses, they can work on writing counternarratives. Antiracist work is a twofold process in which we not only bring attention to the racist discourses at work in our society, but also create spaces to document the perspectives and lived experiences of those who are often silenced, ignored, dismissed, ridiculed, demoralized, and dehumanized in mainstream media.

Works Cited

Abad-Santos, Alexander. “The First Indian-American Miss America Has Racists Very, Very Confused.” The Wire 16 Sept. 2013. <http://www.thewire.com/entertainment/2013/09/first-indian-american-miss-America-has-racists-very-very-confused/69439/>. Web.

Adummg. “Racism in Aladdin.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u8q11sAg2zg. YouTube, March 2, 2010. Web. February 21, 2017.

Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and Racial Inequality in Contemporary America (4th ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2014. Print.

“A Lot of People Are Very Upset That an Indian-American Woman Won the Miss America Pageant.” BuzzFeedNews 15 Sept. 2013. <http://www.buzzfeed.com/ryanhatesthis/a-lot-of-people-are-very-upset-that-an-indian-american-woman#.bh7BrnmX6>. Web.

Gibson, Margaret. Accommodation Without Assimilation: Sikh Immigrants in an American High School. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988. Print.

Hamlin, Kimberly. “Bathing Suits and Backlash: The First Miss America Pageants, 1921-1927.” There She Is, Miss America: The Politics of Sex, Beauty, and Race in America,s Most Famous Pageant.” Eds. Elwood Watson and Darcy Martin. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. 27-51. Print.

Kinloch, Valerie. “The Rhetoric of Black Bodies: Race, Beauty, and Representation.” There She Is, Miss America: The Politics of Sex, Beauty, and Race in America’s Most Famous Pageant.” Eds. Elwood Watson and Darcy Martin. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. 93-109. Print.

Kynard, Carmen. “Teaching While Black: Witnessing and Countering Disciplinary Whiteness, Racial Violence, and University Race-Management.” LiCS, 3.2 (2015): 1-20. Print.

“Miss America History.” Miss America 14 Aug. 2015. <http://www.missamerica.org/our-miss-americas/miss-america-history.aspx>. Web.

“9 Racist Tweets Against Miss America Nina Davuluri.” IBN.Live 17 Sept. 2013. <http://www.ibnlive.com/news/buzz/9-racist-tweets-against-miss-america-nina-davuluri-639456.html>. Web.

Lippi-Green, Rosina. English With an Accent: Language, Ideology, and Discrimination in the United States (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Martinez, Aja. “Critical Race Theory: Its Origins, History, and Importance to Discourses and Rhetorics of Race.” Frame, 27.2 (2014): 9-27. Print.

Martinez, Aja. “A Plea For Critical Race Theory Counterstory: Stock Story versus Counterstory Dialogues Concerning Alejandra’s ‘Fit’ in the Academy.” Composition Studies, 42.2 (2014): 33-55. Print.

Nakagawa, Kathy and Arzubiaga, Angela. “The Use of Social Media in Teaching Race.” Adult Learning, 25.3 (2014): 103-110. Print.

Pimentel, Charise. “Critical Race Talk in Teacher Education Through Movie Analysis: From Stand and Deliver to Freedom Writers.” Multicultural Education, 6.1 (2010): 49-60. Print.

Pimentel, Octavio. “An Invitation to a Too-Long Postponed Conversation: Race and Composition.” Reflections: Public Rhetoric, Civic Writing, and Service Learning, 12.2 (2013): 90-103. Print.

Pimentel, Octavio, Charise Pimentel, and John Dean. “The Myth of the Colorblind Writing Classroom: White Instructors Confront White Privilege in Their Classrooms.” Performing Anti-Racist Pedagogy in Rhetoric, Writing, and Communication. Eds. Condon, Frankie and Young, Vershawn. South Carolina: Parlor Press, In Press.

Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People. Dir. Jack Shaheen. Media Education Foundation, 2006. Film.

Shaheen, Jack. Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People. Northampton: Olive Branch Press, 2014. Print.

Share, Jeff. Media Literacy is Elementary: Teaching Youth to Critically Read and Create Media. New York: Peter Lang, 2015. Print.

Tatum, Beverly. “Defining Racism: ‘Can We Talk?’.” The Race Reader. Ed. Gilbert Rodman. New York: Routledge, 2014. 25-32. Print.

Author Bio

Charise Pimentel, Ph.D., is an associate professor at Texas State University in the Department of Curriculum & Instruction within the College of Education, where her areas of specialty are race and education, bilingual education, multicultural education, and critical media literacy. The courses she teaches include Multicultural Teaching and Learning, The Politics of Language, Bilingual Education Principles and Practices, and Literacy Education for Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Children. She has published widely in top peer-reviewed journals and has contributed several book chapters to edited books. Her most recent works include an edited book, From Uncle Tom’s Cabin to The Help: Critical Perspectives on White Authored Narratives of Black Life, and a book, The (Im)possible Multicultural Teacher: A Qualitative Study on White Teachers’ Multicultural Work, that is currently available.