Essence of Mom 2.0: Media, Memory,

and Community across an Extended

African American Family

Introduction

In their article on technology-rich community literacy work, David Dadurka and Stacey Pigg indicate that although impressive research has been done in this area, gaps remain. Describing how much of the research has focused on snapshots of early-adopting youth working in formal educational settings, they call for research that includes multiple age groups, takes place outside of school settings, and captures longitudinal development (Dadurka and Pigg 16-17). Other work on digital literacy development outside of school contexts has focused on youth popular culture—fan communities (Thomas; Black), social networking sites (Williams; boyd), and online games (Chen; Duncan)—and has tended to showcase aspects of community digital production shaped by these interests. As Lisa Nakamura argues, these studies of digital culture tend to focus on the practices of “average” technology users, overwhelmingly seen as white and male (although there are notable exceptions, such as Banks’s Race Rhetoric and Technology and Digital Griots). As a result, there is a need for research investigating the varied digital practices of diverse racial, ethnic, linguistic, cultural, and age groups.

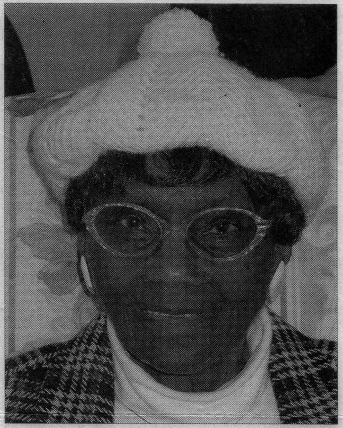

Along with the other pieces in this collection, this project addresses these gaps, focusing on the six-year process Lillie Jenkins, one of the co-authors, undertook with her extended family to create a digital text documenting the life and legacy of her mother, Martha M. “MJ” Jenkins. An African American woman born in 1929, MJ led an extraordinary life as a nurse, cook, and church leader who raised seven children and served God and her rural Georgia community through her care and company, especially in the form of lively stories and expressions, cooking, and African American textile arts. Following Jenkins family tradition, MJ served as the woman of her generation who remembered and passed on family practices, genealogies, and stories, infusing these traditions into her everyday interactions with her children and especially into special occasions like holidays and the family’s annual gathering. After MJ’s passing in 2008, Lillie realized that she had become the designated family “historian” of her generation, the child who’d taken the most interest in MJ’s family lore and traditions. In part to document and pass on this inheritance and in part to work through her grief over MJ’s passing, Lillie began work on a family history project whose intended audience was her extended family: MJ’s surviving siblings, children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews. This project, which became known as the MJ Project, grew in size and complexity in terms of both its content and its format between 2009 and 2014, involving members of the extended Jenkins family, with Lillie serving as compiler and primary author.

[click image to enlarge]

[click image to enlarge]

The creation of the MJ Project highlights important questions about both the production and the uptake of digital texts, foregrounded by the differences between its cultural context and that of existing work on digital production in community contexts. This work is often discussed in terms of participatory culture, defined by Henry Jenkins et al. as a cultural context in which production of texts is facilitated, supported, and valued by an affinity community constituted around a shared interest (7). Research in this tradition has focused on youth popular cultures involved in fan fiction, television fandom, gaming, and meme-remixing. This scholarship focuses especially on the circulation of cultural tropes and narratives, with a strong emphasis on the read/write remix culture theorized by Lawrence Lessig. As such, broad dissemination and appropriation of existing content are central features of this widespread understanding of participatory culture. However, focusing on an example of community digital production like the MJ Project created in a multi-generational, racially marginalized community context expands our understanding of how digital literacy develops over time (especially the connections between print and digital literacies and between literacy resources gleaned from various areas of life) and how such a project should be circulated.

Expanding our sites of research to communities like the Jenkins family has important implications for both our theories and our methods. As Tabetha Adkins describes in her reflection on studying Amish literacy practices, questions about relevance, access, and privacy arise when working with a community that neither research ethics (embodied by IRB [Institutional Review Board] protocols) nor existing scholarly frameworks adequately account for. While Adkins discusses how the research protocols her institution’s IRB called for didn’t address the practicalities of gaining access to community members’ literacy stories, the Office of Research Compliance and Integrity at Julia’s institution stated that it saw the MJ Project as a family history project, outside the purview of IRB. The Jenkins family, however, had serious concerns about how the MJ Project—which also includes MJ’s children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews—would circulate to outside audiences, including through this publication. They also voiced concerns about appropriation and ownership that participatory culture scholarship often paints much more positively. Based on a previous experience in which video filmed at a family gathering was posted on Facebook, exposing family members to potential criticism in the local community when the footage was viewed out of context, the Jenkins family was highly conscious of the risks associated with digital circulation, which informed their concerns about privacy when developing the MJ Project.

We then move on to consider the Jenkins family’s process of deciding whether and how to publish the MJ Project content digitally, putting writing studies scholarship on access and infrastructure in dialogue with work on digital community projects/digital heritage and critiques of the embrace of unrestricted circulation of digital content. This analysis highlights the continuity between the distinctive oral, print, and digital literacy practices of the Jenkinses as an African American family and their sophisticated assessment of the affordances and limitations of digital publication for sharing/preserving this heritage within the family circle. The result is a call for greater attention to the pitfalls, as well as the potentials, of engaging in participatory culture with family heritage material, where the experiences and concerns of a community of color raise awareness of issues that impact all users of participatory digital technologies.

A Note on the Title and Banner

A lifelong photographer, Lillie took a picture as a teenager of the familiar scene of everyday objects on MJ’s bedside table as a study in still life composition. She titled the picture “Essence of Mom” and proudly showed the print to her mother. MJ didn’t appreciate having her private business showcased through this record of her personal objects and asked Lillie not to share the photograph. By referencing that decades-old photo in the title of this piece, we frame our project in terms of the push and pull between technologies’ ability to document and share personally and culturally meaningful texts and the concerns communities of color in particular have about the way those representations may be received and interpreted as they circulate to outside audiences.

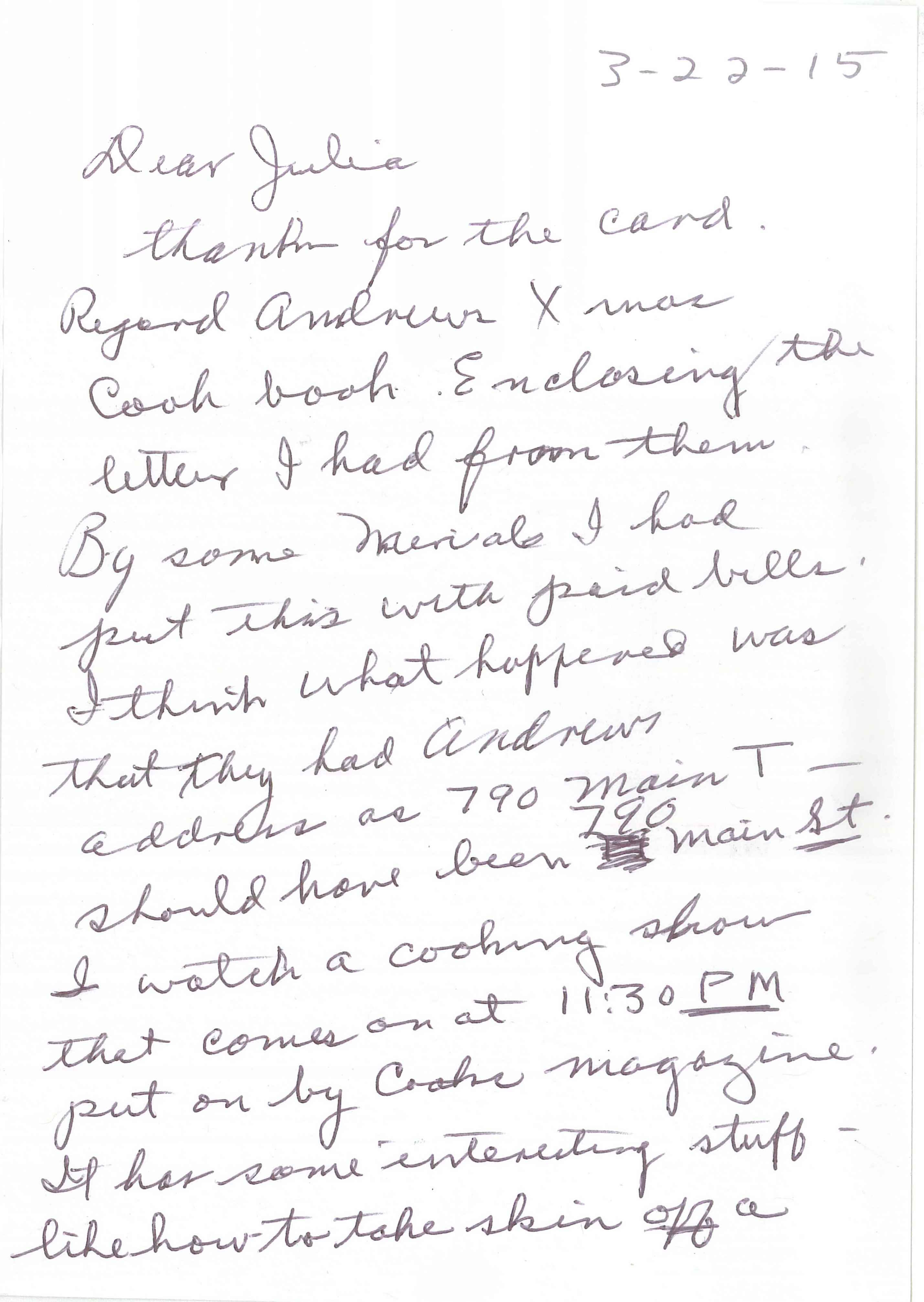

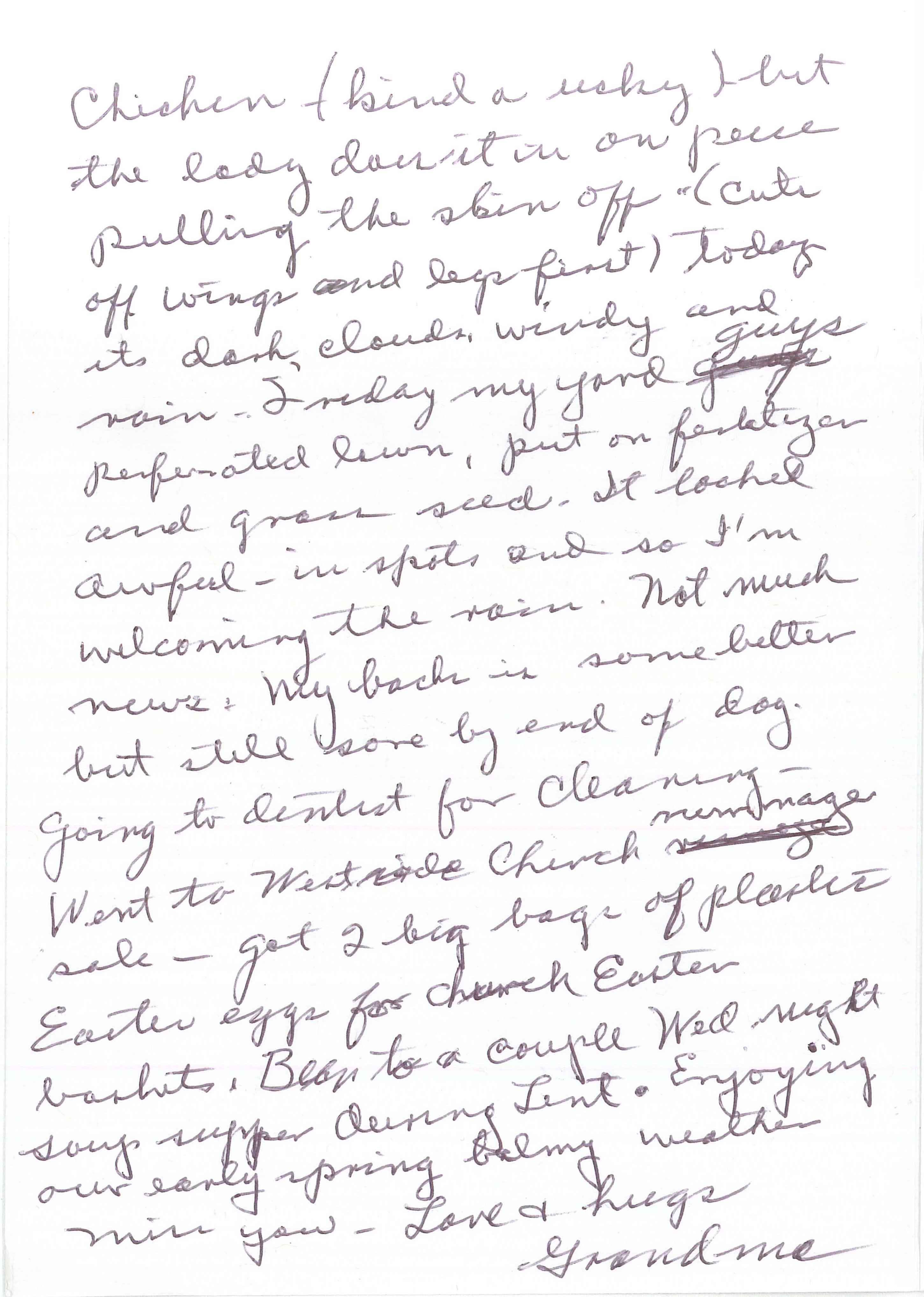

The design of the banner also reflects the heritage traditions with which the piece deals, and serves to link those of Lillie’s family—the focus of this essay—and those of Julia’s family, by way of explaining (one of) her investments in this project. As explained below, MJ’s letters formed the initial core of the MJ Project. When Lillie shared copies of MJ’s letters with Julia as they began work on this piece, Julia was struck by how similar those letters were to the ones she exchanged with her grandmother, from the use of religiously themed greeting cards and lined notebook paper as stationery to the Palmerston-esque handwriting to letters’ mixture of advice, family stories, local news, and sayings.

[click image to enlarge]

[click image to enlarge]

[click image to enlarge]

Julia, like Lillie, began exchanging letters with her grandmother after she moved away from home to attend school. These letters have become one of the main threads of their relationship. As a nod to their families’ parallel literacy traditions, Julia commissioned her grandmother to write out the title of this piece, to create an opening visual that would evoke the look of MJ’s letters, present the essay’s central ideas, and signal the personal as well as critical investment of both authors.

Development of the MJ Project as Family Literacy Practice

Although the scale and focus of the MJ Project make it unique to the Jenkins family, material contained in it and its production as a facilitated community text reflect long-standing literacy family literacy practices. In addition to the project’s origin with MJ’s letters, the process of soliciting content for the project and Lillie’s lead role in producing the project drew on the ways in which the Jenkins family has traditionally produced documents for its annual family celebrations. As Deborah Brandt (“Accumulating Literacy,” Literacy in American Lives), Annette Harris Powell, and Cynthia L. Selfe and Gail E. Hawisher have argued, literacy accumulates, meaning that individuals use literacy practices they’re familiar with to approach new tasks. While Powell and Selfe and Hawisher focus on connections between home/family literacy practices and educational ones, the emphasis here is primarily on literacy practices within a family context, although there is some influence of formal education through Lillie’s participation in two university courses that focused on documenting and representing literacy using digital media. Similar to what David Barton and Mary Hamilton observed among working-class Lancastrians, the Jenkins family has long-established literacy practices developed around certain kinds of texts that shaped the form and structure of the MJ Project as a new literacy task. Furthermore, as Sara Webb-Sunderhaus argues in her work on the relationship between the family and school literacy experiences of Appalachian college students, the contributions family members make to literacy development aren’t always direct. Like Webb-Sunderhaus, Lillie found that contrary to her original expectation that family members would contribute directly to the MJ Project by sharing family documents they’d saved or by writing original content, she needed to expand her understanding of “participation” in the production of the text to include other mechanisms of communication and interaction familiar to her family, especially phone conversations, group discussions at family gatherings, and the sending of notes and photos via mail and email.

When Lillie left home to attend college, and throughout her adult life—moving from Georgia to California, back to Georgia, and then on to Texas and Ohio—she and her mother regularly exchanged letters. Lillie wrote to update her mother about her life, and MJ wrote to pass on stories and advice and to update Lillie on events in their hometown in rural Georgia. In addition to regular phone calls, their correspondence became a major part of Lillie’s adult relationship with her mother, allowing them to revisit and add to the store of family lore, sayings, advice, and home knowledge that MJ had cultivated in Lillie and her siblings throughout their childhood.

Although Lillie was especially invested in this correspondence because of her close relationship with MJ and the distance between them, MJ wrote regularly to all her children as well as to other friends and relatives. Where MJ’s children were concerned, these letters extended the kind of informal cultural education that had gone on throughout their childhood, in which MJ had taught her children about love, family, education, and other “home truths” through stories and sayings. (For discussion of MJ as a teller of traditional African American stories, jokes, and proverbs, see Jenkins, forthcoming.)

Although not directly related, the MJ Project and the dynamics of its production also grew out of two other ongoing Jenkins family literacy practices in which Lillie plays a central role. The Jenkins family has an annual weekend-long gathering in the rural Georgia community where Lillie and her siblings grew up. Every year Lillie prepares a “memento book” for the reunion that records important events in family members’ lives (graduations, weddings, births, passings, business news, et cetera), along with a brief account of the family’s history. Leading up to the gathering, family members send Lillie news via letter, email, and phone conversation, to which Lillie adds a welcome note (unique to each year) and reminds attendees about agreed-upon “ground rules” for behavior at the gathering. The memento book is distributed in print format at the beginning of the gathering, ensuring that relatives from near and far are equally informed about family news and the expectations for conduct. From 1991 to 2010, Lillie also kept another set of family records in a family Christmas book. Her initial purpose was to record information about the annual Christmas program the family had been putting on since Lillie’s childhood. To complement a tradition that MJ began of audio-recording or videorecording the program, Lillie used a commercially produced memory book to record stories and gather photographs to record family Christmas gatherings as well as the program itself. During that period, at extended family gatherings during holidays, reading the entries from the previous year—written by Lillie—became another Jenkins family Christmas tradition.

[click image to enlarge]

[click image to enlarge]

Lillie’s interest in family Christmas traditions is representative of her role as MJ’s successor as family historian. In the Jenkins family, one person in each generation becomes the family historian, the one who remembers the family’s history and documents events and traditions. MJ served in this role in her generation, and of her children, Lillie was the one who showed an interest in the family tree, MJ’s collection of multigenerational family photographs, and the stories behind the family’s traditions. When Lillie recognized the significance of the store of family history and traditional knowledge MJ was passing on to her, she began writing down MJ’s stories to preserve them. And because of Lillie’s own interest in family history and the African American cultural traditions MJ passed on to her children—a topic Lillie pursued further in graduate coursework—she also began, over the years, to write down her reflections on her experiences with MJ and her reactions to these stories in the form of short stories and poems.

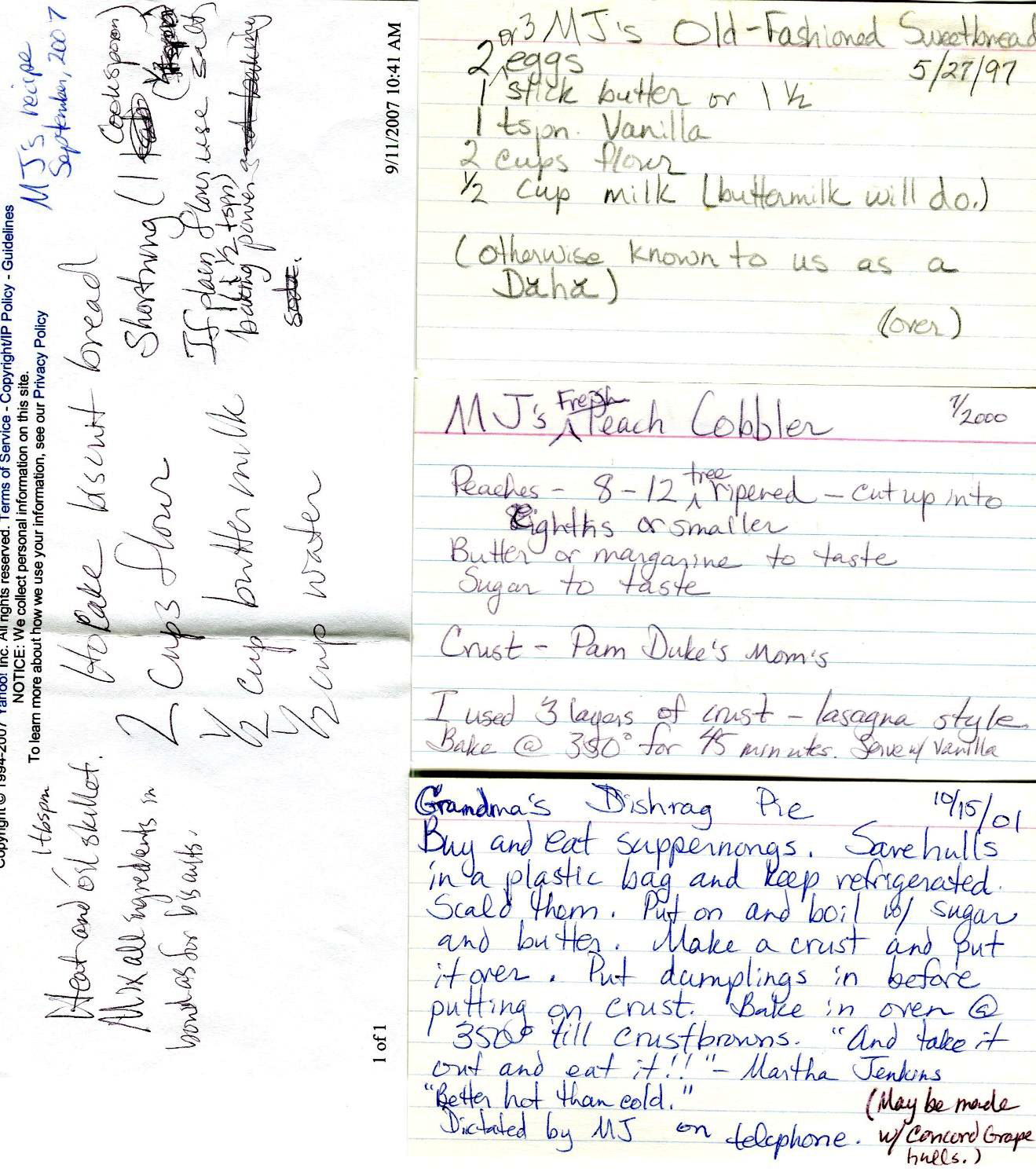

Lillie starts the process of transcribing and digitizing all the letters, cards, and notes she received from MJ over the course of her adult life, about 120 pieces in all. Although relatively little work has been done on contemporary personal letter writing practices (see Besnier and Guerra for a review of the literature on letter writing), the small body of existing research provides interesting parallels and valuable context for the Jenkins family’s letter writing practices. MJ’s letters are what Konstantin Dierks calls familiar letters, “a mode of letter writing devoted to the expression of affection and duty among kin, family, and friends” (31) that is characterized by expressions of emotion and discussions of everyday life. What made MJ’s familiar letters so valuable for Lillie’s purpose of preserving MJ’s legacy was their inclusion of MJ’s familiar sayings, witty tone, and allusions to family events and stories, all hallmarks of her speech and reflected in the “spontaneous,” “natural” (35) tone of her familiar letters. As Frances Austin has argued, this kind of ongoing, meaningful correspondence among family members is facilitated when they disperse and begin using letters as means of maintaining their relationships with one another. As was the case in Lillie’s family, MJ’s familiar letters typically serve to preserve connections among close relatives who become separated by distance, and whose content—among other things—presents current events and new information in light of existing shared values and experience. In his research on letter-writing practices within close family and friend networks of South Pacific Islanders, Niko Besnier situates letters as similar to and deeply influenced by oral communication, sharing many of the conventions of oral genres like advice-giving and gossip (79, 91). These parallels reflect the typical parent/child relationship of correspondents: like Lillie and her mother, Besnier’s letter writers were often parents (living on a remote Pacific atoll) and their adult children (who left the island to work). Both Besnier’s parent-writers and MJ filled their letters with news from home, as well as with the stories, sayings, and guidance they hoped would remind their children of the traditions and values of their home communities.

If documenting the family tradition of letter writing was one important purpose of the MJ Project, looking forward to the family’s future was the other. Lillie wanted her younger relatives to see themselves as participating in a rich history of letter writing, both as a form of creative expression and as a way to connect to their family and its traditions. By including younger relatives’ letters in the MJ Project, Lillie invited her relatives to invest them with the kind of meaning she read into MJ’s letters, stories, recipes, and textiles, seeing these not just as some stacks of old letters, but also as representations of the Jenkins family’s unity and values.

Lillie’s difficulties collecting letters from her siblings parallel Juan C. Guerra’s findings about the role letters play in the transnational community he studied, whose members migrate between Chicago and a cluster of villages in central Mexico. Participants told Guerra that while still living in Mexico, they’d saved years’ worth of letters from relatives living in Chicago. However, they discarded the letters once they joined these family members in the United States. Guerra interpreted this as reflecting the role the letters played in different life circumstances: “Now that they had finally and permanently joined members of their families from whom they had received letters, the letters no longer filled the emotional needs they once had” (98). Similarly, for Lillie’s siblings, especially those living near MJ in Georgia, the letters might have served a more instrumental purpose (helping them stay informed about local news in their hometown) than they did for Lillie, living hundreds of miles away, for whom MJ’s letters constituted a major point of connection with the community in which she’d been raised. The different attitudes Lillie and her siblings had toward MJ’s letters were an early signal of the variety of relationships and memories family members had of MJ, prompting Lillie to (re)shape the MJ Project in light of the community’s contributions.

These conversations didn’t begin as discussions of MJ. Instead, as Lillie and her siblings talked about what was going on in their lives, they found themselves continually referring to MJ’s sayings and stories while they served as one another’s advisors and sounding boards. Since these conversations occurred within the family circle, their store of common experiences, sayings, and stories derived from MJ’s home truths, which naturally infused Lillie and her siblings’ conversations. Stephen J. Zeitlin, Amy J. Kotkin, and Holly Cutting Baker argue that this kind of purposeful retelling is one of the main functions of family folklore, bringing the family’s collective experience to bear on current events, eliciting “what we need from them now” (8). In these conversations, Lillie and her siblings interwove advice, family lore, and current events just as MJ had done in her letters, using signal phrases and abbreviated references—another community-building use of family folklore identified by Zeitlin, Kotkin, and Baker—to refer to their shared memories to make sense of their current lives and times in light of their memories of MJ. Lillie used these conversations to reconstruct memories about times spent with MJ, her advice and stories, and the rules about housekeeping, cooking, community, thriftiness, and other everyday practices that MJ imparted. She added these community-composed stories about MJ to the accounts written by her brother and nieces to construct the multidimensional, community-authored portrait of MJ found in the project.

Reflecting on the relationship between what she learned in these courses and the MJ Project, Lillie comments:

[The] technology information that I was able to gather from this class is definitely going to be useful to me in the present [with the MJ Project]. And I’m even thinking now how will this be useful to me in the future, by saying “OK, I can read my mom’s letters. OK, buy a Flip camera [the kind used in the class].” I don’t know how much they cost, but get a camera like that or use my own digital camera which has a moviemaking feature. And just read those letters and then download the letters, my reading of them, to my computer. […] I can see myself using that.

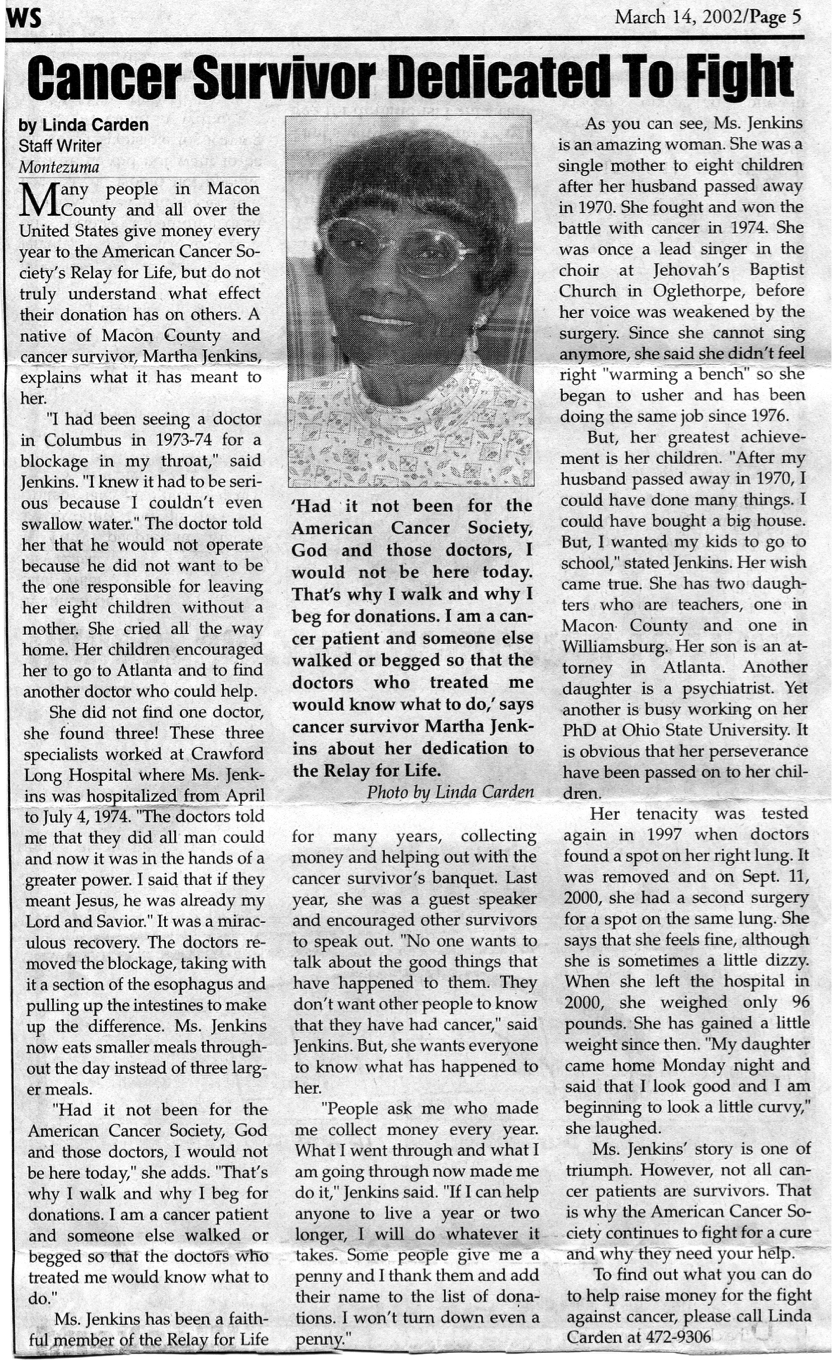

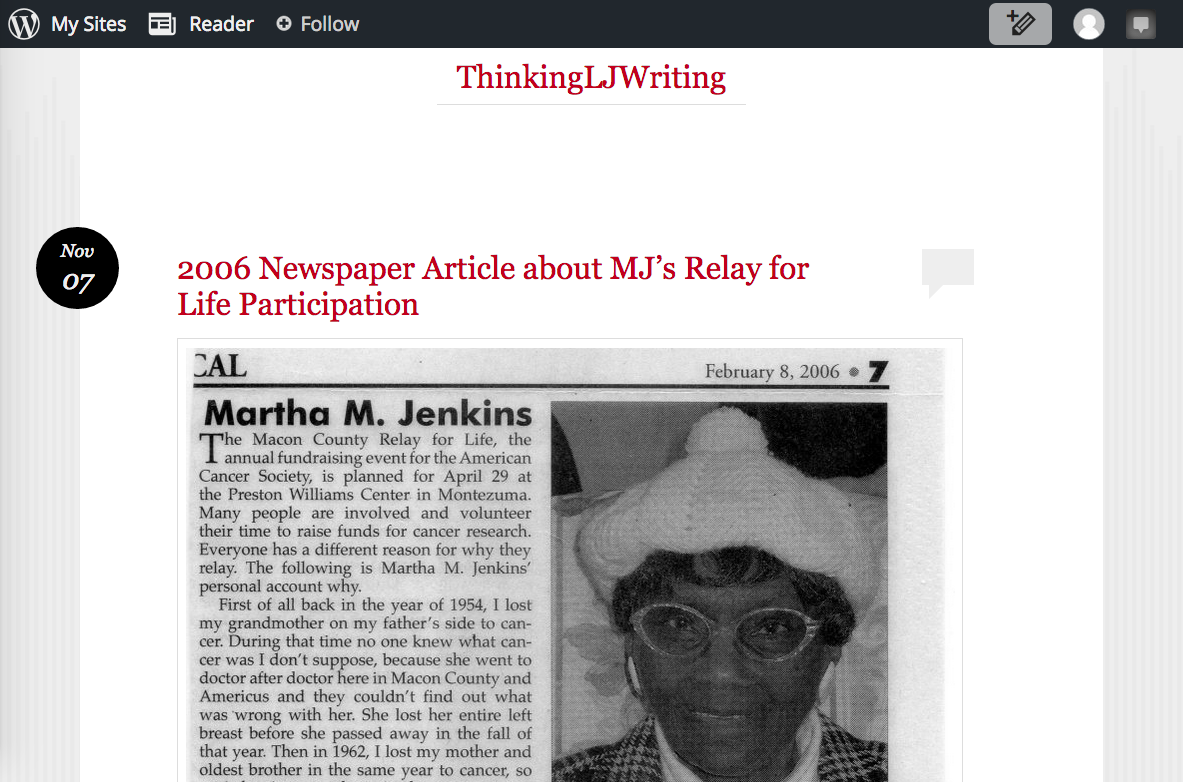

Her plans for including video and audio, as well as written text and images of MJ’s letters illustrate the increasingly multimodal plans Lillie is developing for the MJ Project. In preparation for parts of the project that demonstrated MJ’s resilience in the face of her ongoing battle with cancer and her commitment to serving her community, Lillie gathers media that communicates growth, trauma, stasis, mobility, service, and patriotism, a selection of which is represented here:

[click image to enlarge]

The digital composing expertise with which Lillie left the class did affect the MJ project. Although Lillie shelved the course projects after the term ended and did not incorporate them into the MJ Project, the course’s focus on multimodal storytelling prompted her to begin going back through decades’ worth of photographs, short stories, poems, and jotted notes she’d compiled over the years.

[click image to enlarge]

[click image to enlarge]

Although some of these dishes were Jenkins family variants of familiar Southern classics (like sweet potato custard), others were family specialties (like Grandma’s Dishrag Pie and Peach Slosh) that called to mind dinners and special occasions past and present at the old farmhouse in rural Georgia where MJ raised her children and where the annual family gathering is held.

After MJ’s death, recipes also became a way of preserving her memory among Lillie and her siblings. One November evening on the phone with her older sister, Lillie reconstructed MJ’s recipe for prune puffs, the name the family coined for MJ’s variation on prune turnovers. To share this piece of family history more widely, Lillie used the reconstructed recipe to make a batch of prune puffs in honor of her brother’s birthday later that month, texting him a picture of the finished product so he could vicariously enjoy/envy the fruits of Lillie and her sister’s reminiscence.

[click image to enlarge]

For Lillie, the most valuable outcome of sharing the MJ Project draft was the opportunity it provided for other family members to construct their own memories and legacies of MJ. This occasion provided an opportunity for what Roger I. Simon calls “remembering together, a publicly-shared invitation to reflect on a shared object of focus” (89). In this case, Lillie’s draft of the MJ Project provided the impetus for communal recollection, and Lillie attended to the discussions the project sparked in order to incorporate these responses into the final version.

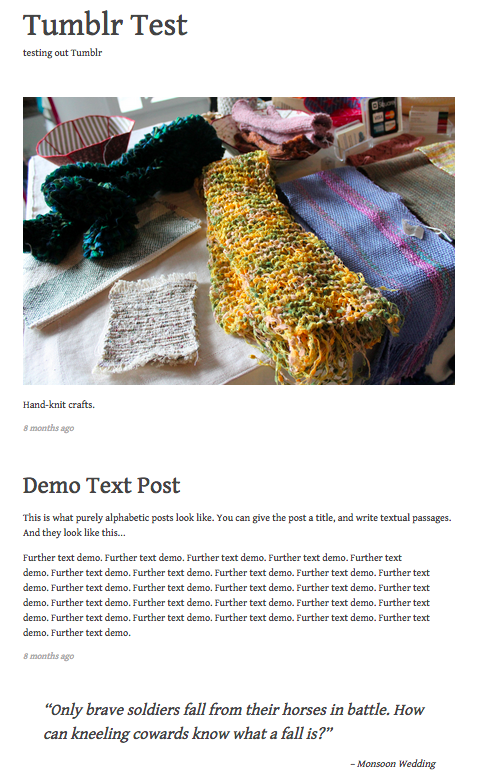

The results of this “remembering together” shaped the MJ Project considerably. While Lillie had always been invested in family history, stories, sayings, and recipes, and in the written texts and photographs that documented them, other family members were deeply invested in other legacies MJ had left behind. Several family members’ memories of MJ focused on the textiles and home decor crafts—especially quilts—MJ had made to commemorate family members’ life milestones, such as going off to college, retiring, or having a child. Lillie discussed MJ’s textile arts to some extent and had included some photos of the quilts and embroidery MJ had given her over the years, but the family’s response to this aspect of the project prompted Lillie to expand this section into a full-fledged chapter. Jenkins family members affirmed African American quilter Mensie Lee Pettway’s argument for the significance of quilts and their role in family legacies: “A lot of people make quilts just for your bed for to keep you warm. But a quilt is more. It represents safekeeping, it represents beauty, and you could say it represents family history” (294, qtd. in Sohan). Family members’ input expanded the scope of the project and positioned this material dimension of African American folk tradition more centrally. To accompany this expansion, Lillie visited nearby relatives’ homes during the gathering to photograph their quilts.

[click image to enlarge]

[click image to enlarge]

According to Zeitlin, Kotkin, and Baker, physical memorabilia objects like MJ’s quilts serve as touchstones for memory, occasioning the kind of group reminiscence Lillie observed at the family gathering: “[B]y gathering around ourselves treasured objects from different times of our lives and our histories, we experience different eras at the same moment and in some way bring the totality of the past to bear upon the present” (201). A simultaneous limitation and strength of physical memorabilia, Zeitlin, Kotkin, and Baker explain, is its singularity (203):each of MJ’s quilts can only be in one place at a time, which can create tension over who “controls” that aspect of family heritage. However, the incorporation of photographs of MJ’s quilts underscores one of Lillie’s main goals in creating the MJ Project: she wanted to preserve and share MJ’s legacy throughout the extended family, engaging older family members in creating a community portrait of their mother and passing on to younger members a sense of the rich history and traditions presented by the grandmother they might not have had a chance to know well. The MJ Project’s digital format made this possible, allowing for the replication and wider distribution of family memorabilia—as well as stories and memories—even if this ease of circulating and reproducing created other dilemmas, discussed below.

Furthermore, the fact that the members of the Jenkins family didn’t alter the draft of the MJ Project that Lillie presented to add their feedback or impressions directly echoes Mark B. Gaved and Paul Mulholland’s finding that groups tend to be less likely to embrace new technologies if they already have existing communication systems that meet their needs. However, family members did contribute to and shape the MJ Project in ways that were familiar to them, through conversation and information sharing. Just as Lillie had worked on MJ’s stories, sayings, and recipes for the project in the context of typical phone conversations with her siblings, group reminiscing--a typical activity at family gatherings--clued Lillie in to aspects of MJ’s legacy that were particularly important to other family members. Finally, the practice of sending photos and recollections of MJ’s quilts and other home decor objects via mail and email mirrors the long-standing Jenkins family tradition of sending Lillie family news updates for the annual gathering’s memento book. In both cases, Lillie serves as the collector and synthesizer for these projects, a clearinghouse of family information who created a narrative for MJ’s legacy from the raw material contributed by other relatives.

Although Lillie managed the document, selecting its contents and writing the text, family members were closely involved in the development of the MJ Project, illustrating oral collaborative methods of creating a participatory text. From Lillie’s original vision of a compendium of MJ’s letters to a wide-ranging portrait of MJ’s life and legacy across genres and modalities, the evolution of the project reflects the interweaving of long-standing family literacy traditions with new technologies and formats through the use of new digital presentation media. The following section discusses the considerations, conflicts, and decisions Lillie and the Jenkins family went through while considering how the MJ Project should be presented and shared, bringing up questions about design, participation, privacy, and circulation.

Sharing a Community-Based Text

As Lillie worked on the MJ Project over the years, she thought about how to involve other family members in contributing content and distributing it. the project grew in scope and family members continued to share photos and other media with Lillie. Distributing it in print form--especially in color, to do justice to the embedded photos, as the family does with the memento book for the the annual gathering--became prohibitively expensive as the project grew. Based on the collaborative process Lillie used to compile the project, she wanted to invite family members to continue contributing to MJ’s legacy, rather than produce a static, solo-authored text. This wish was prompted in part by Lillie’s desire to pass on the role of family historian to the next generation the way MJ had passed it on to her. Lillie thought a digital platform might encourage one of her nieces or nephews to become interested in working on the family’s history. Considering concerns, Lillie and Julia began discussing digital platforms to house the MJ Project during the fall of 2014. Especially in light of younger relatives’ use of social networking sites, Lillie and Julia began testing different Web 2.0 platforms as options for housing MJ Project content. The idea was to post material from the MJ Project there and invite family members to contribute their own material directly in the forms of photos, videos, and written content. The other major consideration affecting their evaluation of digital platforms concerned circulation: making MJ content accessible to family, but not to the general public or to corporations. These considerations took Lillie and Julia into discussions of online privacy and information design, eventually drawing on the fields of digital heritage, community media work, and digital advocacy.

As mentioned above, Lillie built the MJ Project in Microsoft Word, a program installed on her personal computer with which she was thoroughly familiar. This may seem like a strange choice for a born-digital project incorporating multiple media in which Lillie planned to engage her family as collaborators. However, Word had several features to recommend it for Lillie’s purposes. For Lillie, Word functioned as what Jessica Helfand calls an “original open-source technology” (xvii) in her discussion of scrapbooking as a homespun multimodal practice of personal narrative and local history documentation. Word’s image and written-text layout options allowed Lillie to mix written text with images, and she used its document design features to create chapters, sections, and a table of contents readers could use to navigate the document. While other platforms like Adobe InDesign and Microsoft Publisher might suggest themselves for this kind of task, as Otto Leopold Tremetzberger argues, the purpose of digital community projects like the MJ Project is not the use of cutting-edge technologies but rather “challeng[ing] people to participate, interact, and change” (54), especially using technologies that are readily available, echoing Daniel Anderson’s case for using “entry-level multimedia” (40). In Lillie’s case, once she returned to the MJ Project after taking digital media production classes at the local university, without access to campus media labs and instructional staff, she returned to what Anderson calls “familiar literacies” (40) to develop the project. Word had the affordances Lillie needed and was a match with her existing technological resources and skills, making it an accessible platform for the MJ Project. As a document stored on Lillie’s personal computer, it also met the family’s requirements for privacy and control over content (discussed below).

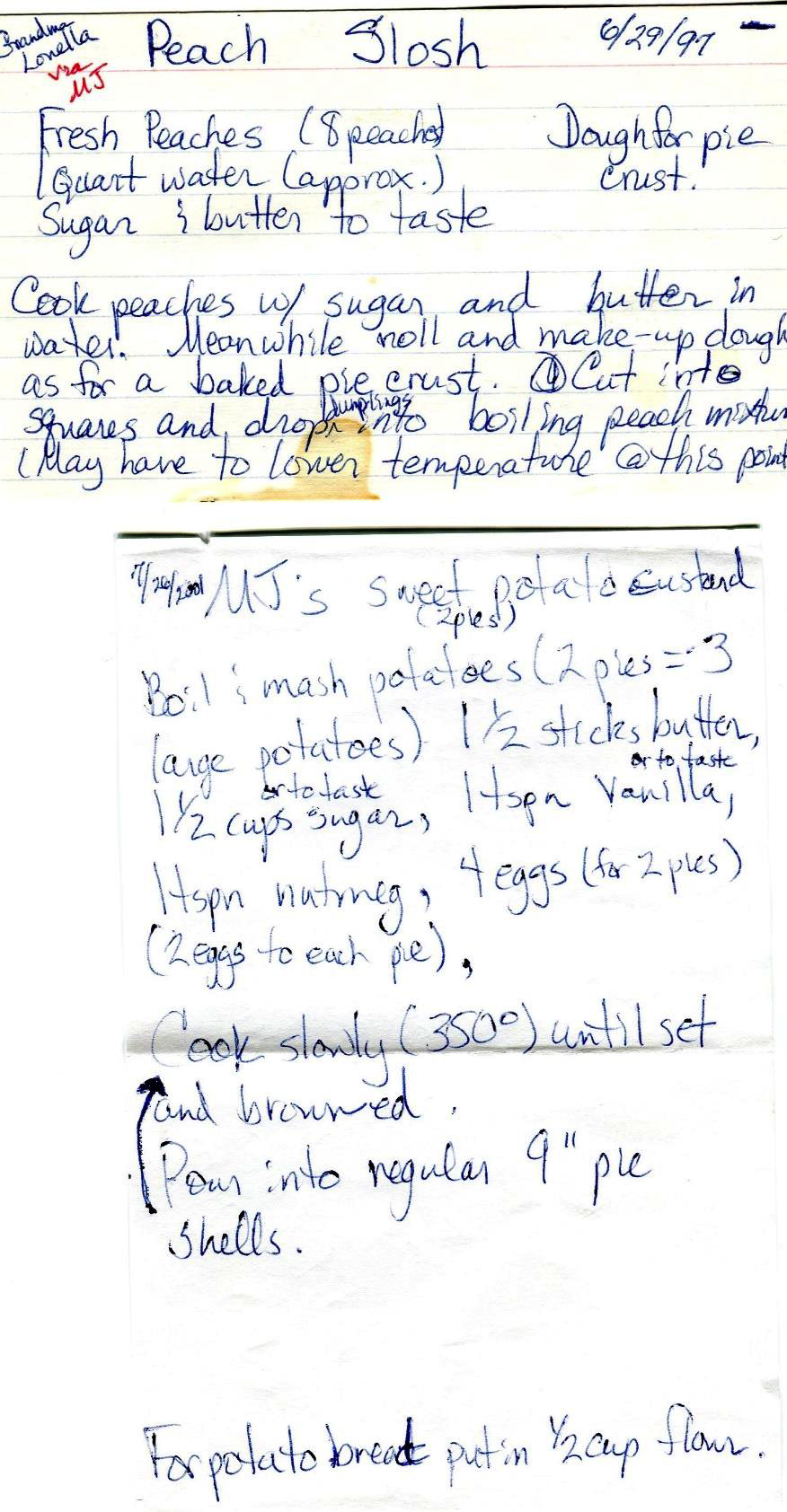

Given the central role photos played in the content family members shared with Lillie, Julia looked into media-intensive social media platforms that allowed for written text, like Instagram and Tumblr; text-centric sites like WordPress; and general-purpose social media sites like Facebook. Based on the ways in which Lillie had observed younger relatives using smart phones at family gatherings to document events and communicate with one another, Julia focused on applications with easy-to-use smart phone apps and minimal steps for posting to encourage family members to contribute content. Julia and Lillie created several test pages/groups in various platforms to consider the affordances of different ones.

[click image to enlarge]

[click image to enlarge]

Based on her experience gathering content and working with family members between 2009 and 2014, Lillie planned to serve as the creator and moderator of the MJ Project’s online presence, inviting family members to post content in multiple media and to comment on one another’s contributions. This process would virtually reenact the kind of collaborative reminiscence that had occurred in person as family members perused the draft of the MJ Project on Lillie’s laptop at the 2014 gathering. As a result, one of Lillie’s major concerns was that the platform be easily accessible, and Julia performed some simple usability tests to determine how easy it was to post and comment on these platforms, especially using mobile devices. This accessibility would be instrumental in contributing photos like the quilt pictures Lillie had begun receiving after previewing the MJ Project at the 2014 gathering.

Like Jeffrey T. Grabill, whose work on community technology partnerships focuses on using participatory design to develop Web projects that meet the needs of their users—not only their designers—Lillie and Julia carefully examined the features different Web 2.0 platforms offered for sharing and building on the MJ Project. Tumblr’s “quote” feature was particularly suited to presenting MJ’s sayings. Lillie appreciated the writing-intensive blog format common to many WordPress templates, which mirrored the look of the MJ Project’s current layout in Word. She also noted that younger members of the family already used Facebook to communicate among themselves, coordinate events, and share photos, making it an appealing choice in terms of familiarity. These digital publishing options offered a variety of appealing affordances.

However, from the beginning, these technological possibilities also brought with them limitations relating to access, resonance with community norms, and content privacy/control. Although Lillie is a proficient user of technology in her personal and professional life, she had never before used Tumblr or WordPress and didn’t have (or particularly want) a Facebook account. This is fairly typical of the older generation of the Jenkins family, with whom Lillie communicates via letter and phone and in some cases email. Although Lillie could contribute content on their behalf, anything housed on a social media site would not be accessible to older, less technologically proficient family members, conflicting with Lillie’s commitment to creating a meaningful record for the family as a whole. She also questioned whether family members would appreciate or engage with a Web 2.0 version of the MJ Project: Would people post at all? Would they engage in the kind of back-and-forth storytelling and reminiscence that characterized the phone calls and face-to-face discussions that had generated so much of the rich material about MJ’s legacy that made up the project so far? Just because family members could converse with one another online via posting, commenting, and tagging, would they? Finally, while Tumblr, Facebook, and WordPress all offer options for making blogs, pages, or groups visible only to specific users through “private” or “secret” settings, users’ content is stored on corporate servers, as with most Web 2.0 applications.1 This raised questions for Lillie about ownership and control of MJ-related material that resonate with ongoing discussions of access, design, and power found in literature on community media projects, digital heritage, and Web 2.0/participatory culture.

Access and infrastructure

Various access barriers complicated Lillie and Julia’s consideration of Web 2.0 platforms for housing MJ Project content, corresponding to James E. Porter’s three dimensions of access that shape the extent to which people use and benefit from technology:

- physical access to technology;

- expertise supporting the use of technology;

- community uptake of and attitudes toward technology.

As described above, some relatives lacked physical access to technology not because they lacked the means to buy computers, smartphones, or Internet service, but because, as older long-term residents of a rural area, they didn’t need digital technologies to communicate. As the MJ Project development process illustrated, existing technologies such as postal mail and the telephone served their needs. While younger family members had considerable technological expertise (evident in their use of social media), because this was a community constituted by kinship bonds rather than explicit or hierarchical structure, there was no framework in place for family members to teach one another how to use new technologies. Furthermore, Lillie’s relative novice status with these Web 2.0 technologies and the fact that she lived in another state would make it difficult for her to serve as a strong advocate or teacher. These concerns parallel the findings of Heather A. Horst, Becky Herr-Stephenson, and Laura Robinson and Megan Finn’s research on peer-based technological literacy support, which emphasize physical proximity and building on existing practices of online communication. Without physical proximity or a shared base of online communication methods to draw on, Lillie saw multiple access barriers to a Web 2.0-based version of the MJ Project.

Still more questionable was whether/how even technology users in the family would take up a Web 2.0 version of the MJ Project. Lillie hoped the Web 2.0 version would capture the kind of lively discussion of shared family history characteristic of Jenkins family gatherings and phone conversations. However, researchers studying digital efforts to record cultural heritage in these naturalistic ways point out how difficult this can be. In their work with Namibian villagers to document traditional herbal lore, Nicola J. Bidwell and Heike Winschiers-Theophilus found their video interviews and observations failed to fully capture important information about the cultural context of participants’ knowledge and practices, such as references to plant samples and preparation methods found in the surrounding area, the spatial organization of practices throughout villages according to gender and status, and the nature of the relationships that underpinned these knowledge systems (207-208). Similarly, Dagny Stuedahl and Christina Mörtberg’s research on preserving and sharing knowledge of traditional Norwegian boat-building practices found that using video and photos to document artisans’ use of traditional woodworking and joining techniques didn’t capture the innate sense of the craft that developed from the frequent feedback novices received when working alongside masters in a physical workshop (113-121). The process of composing the MJ Project had been highly oral and characterized by face-to-face interaction, making Lillie skeptical that a virtual platform would spark the same enthusiasm and participation that had so enriched the MJ Project.

These concerns about digital media’s ability to capture cultural heritage point to the cultural and political implications of infrastructure that Grabill identifies when he argues that “infrastructures shape how we experience information systems and thus shape what is considered information: what is available, what is possible, and what we can do” (91). The features of Web 2.0 platforms like Facebook, WordPress, and Tumblr that Lillie and Julia identified as beneficial—such as low or no cost, the ability to integrate media, mobile accessibility, and privacy settings—reflect areas in which the priorities of the Jenkins family overlap with the hyperconnected priorities of these social media companies. However, these platforms were not designed to capture the kind of give-and-take of face-to-face communication among members of a tight-knit community (especially during lengthy exchanges where each participant holds the floor for an extended contribution) or to include offline members. This, Kristin L. Arola argues, is the kind of sacrifice users make when working with Web 2.0 platforms. While her focus is primarily on the restrictions templates place on the visual design of blog, MySpace, and Facebook pages, Arola also observes that Web 2.0’s conceptualization of content as “posts” encourages contributors to create pithy, self-presenting content, contrasted with the looser generic restrictions imposed by older forms of Web authoring like homepage creation (5-6). As a more traditional blogging platform, WordPress might not restrict the contribution format so much. However, the conventions of blogging—in which an author writes longer, essayistic posts that readers comment on and discuss—also fail to capture the kind of multivoiced conversation that characterized Jenkins family discussions of MJ’s legacy.

All these issues point to the limitations of template-based Web 2.0 applications for an endeavor like the MJ Project. They suggest the need for the kind of project-specific design that Jim Ridolfo, William Hart-Davidson, and Michael McLeod (“Imagining”) describe as resulting from the process of iterative design and user testing they went through with members of the Samaritan community (an Israeli religious minority) to create a digital archive for Samaritan Torah artifacts that would cater to the practices of both scholars studying these texts and Samaritans using them for religious purposes. While Lillie and the scholars cited here all agree on the importance of user control over design and circulation, access rears its head again here. As Ridolfo, Hart-Davidson, and McLeod explain, their Samaritan Torah project drew on the expertise of McLeod, lead software developer at Michigan State University’s Writing in Digital Environments Research Center, and was supported by a $30,000+ Digital Humanities Startup Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Without such technical and financial resources, community digital heritage projects like the MJ Project turn to Web 2.0 platforms that require less technical expertise and funding. Unlike the situation John R. Gallagher describes—in which a Web 2.0 text is designed in tandem by a composer and a platform’s templates and conventions—community-based work like Lillie’s MJ Project; Ridolfo, Hart-Davidson, and McLeod’s Samaritan Torah project; and the heritage projects described by Stuedahl and Mörtberg and Bidwell and Winschiers-Theophilus call for purpose-built platforms that reflect their users’ communicative conventions and values. One of the important contributions these projects make is to create, or alter, existing forms and delivery systems to preserve and communicate diverse cultural content, developing new platforms that reflect genres defined by different audiences and purposes. In addition to the interface limitations described here, which pose problems for usability and viability, social media tools also raise serious ethical questions for communities of users whose values don’t reflect the underlying logics that shape their infrastructure, discussed below.

Privacy, Circulation, and Content Control

Aside from questions about how well various Web 2.0 platforms would resonate with the MJ Project’s composing methods, another major issue Lillie and Julia needed to address when considering publishing MJ content digitally had to do with the logics of circulation built into different Web 2.0 platforms. As scholars like Henry Jenkins argue, one of the major shifts of the Web 2.0 era has been the ability of “amateurs” to share content online and create texts remixing existing content. David Beer, following work on digital labor, goes on to show how this kind of user contribution and remixing is built into the design of Web 2.0 platforms, especially in terms of how they are monetized. Beer’s discussion of the cultural capital that users create for Web 2.0 companies through the metadata they generate views these platforms as archives that “both hold and create cultural data, allowing things to be found” (61). This findability is the source of the Jenkins’ family’s resistance to placing MJ content into Web 2.0 platforms. Such findability is mandatory due what Beer calls the “infrastructures of participation [...] the structures in which such participation occurs; these are the spaces, the walls, the formats within which such unbound archives are located” (53). Such infrastructures of participation produce the kind of “manufacturing of consent” that Heidi McKee discusses in her critique of the use of Web 2.0 applications in the classroom:

when presented with the immediate use of a site—[for instance] wanting to join Facebook to communicate with friends and family—versus the threats to privacy, people will choose the immediate gratification. [...] In exchange for goods and services—to be able to play a particular game or use a particular file sharing site—people will simply hand over—and already are handing over—all sorts of private information to corporations. (283)

The Jenkins family was very sensitive to both of these privacy concerns, especially questions about ownership of material posted on Web 2.0 platforms. The family was less concerned (unlike McKee and Beer) about advertisers and other corporations mining metadata associated with content posted on Web 2.0 platforms than it was about visibility and control of the material posted there. The infrastructure of sites like Tumblr, Facebook, and WordPress is participatory, with tools and default settings designed to encourage sharing with the click of a button:

[click image to enlarge]

And while Web 2.0 platforms have privacy settings with which users can restrict the visibility and sharing of their content, there’s no way to limit corporate access to user content, since it’s all stored on corporate servers. While both Facebook and Tumblr, for example, leave ownership of posted content with the user in terms of copyright, they both claim the right to recirculate that content (see “Terms of Service” for Facebook, Tumblr, and WordPress). This lack of control raised serious concerns for the family, who wanted to maintain greater control over meaningful family history material. However, Lillie’s desire to open the project to the family and encourage them to contribute their own writing, photos, and other MJ-related content encouraged her to float the idea of a social media site to relatives during the 2014 holidays. Citing the concerns discussed here, the family declined, preferring to house the MJ project and other family history texts in a locally-stored files like Lillie’s Word-document version of the MJ Project.

They also expressed concern over the circulation of the MJ Project (and other family texts), stating their desire to carefully manage the circulation of this material. These considerations are consistent with existing family attention to the digital circulation of family texts. For example, for the past several years, the memento book Lillie produces for each family gathering has included a social media statement attendees agree to by signing the register used to record attendance at each year’s gathering. The gathering’s consent form (which focuses on photo and video media and was drafted by Lillie’s brother, a lawyer) states that attendees will not post content from the gathering on their personal social media accounts without the explicit permission of every person represented in it. Although this policy arose in response to family members’ concerns about the visibility of nonconsensual posts, it reflects the Jenkins family’s consistent concern with uncontrolled circulation of family content in digital networks.

Human rights activist and digital advocacy scholar Sam Gregory (“Cameras Everywhere,” “Human Rights” [with Elizabeth Losh]) has written extensively on the ethical complexities that arise when posting and circulating culturally sensitive material online. Gregory is particularly concerned with the circulation of videos documenting human rights abuses, but his critiques of typical arguments for participatory culture and his recommendations for more just design of accessible Web 2.0 platforms connect the Jenkins family’s concerns about circulation to broader discussions of infrastructure, risk, and rights. Discussing the implications of Web 2.0 platforms’ infrastructure, Gregory questions whether the kind of spreadability Henry Jenkins identifies as the basis of participatory culture is just and appropriate in all cases (“Human Rights” 557). In contrast to cases where human rights advocacy video is recirculated in support of the creators’ original purpose, Gregory and Losh point to cases in which media used to document, for example, government repression of citizens, is remixed to undermine the authenticity of the original video, such as the Iranian government’s point-by-point deconstruction of the violent death of Neda Agha-Soltan during the 2011 Arab Spring protests in Tehran. Gregory and Losh focus on the absence of rules to arbitrate in cases where different parties’ rights to digital free expression conflict.

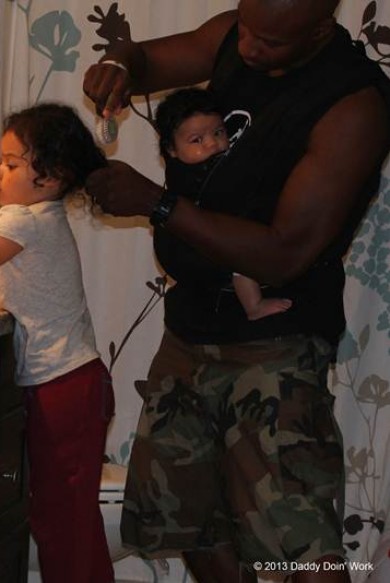

Similarly, the Jenkins family’s concerns centered around the risk of MJ content being inscribed with racist stereotypes about African Americans and recirculated outside of their control. As with human rights video, this kind of counter-remix of media featuring African Americans is unfortunately familiar, underscoring the legitimacy of family members’ concerns. Two recent examples serve to illustrate how such racist counter-remix appropriates media representing Black families by recontextualizing and reinterpreting it: Doyin Richards’ blog post showing himself fixing his older daughter’s hair while wearing his younger daughter in a baby carrier and Adam Harris’s Tumblr posts of a picture of himself tearing up at his wedding.

[click image to enlarge]

[click image to enlarge]

Although many of the shares, comments, and discussions of Richards’ and Harris’ posts adhered to the composers’ original intent--documenting involved Black fatherhood, celebrating an African American couple’s wedding2--others did not. These counter-remixes applied racist stereotypes about African American men to these explicitly family-oriented posts, questioning Richards’ paternity and dedication (see Richards) and Harris’s character and fidelity (see Harris). The same sharing affordances that allowed Richards’ and Harris’ original posts to garner tens of thousands of views, likes, comments, and shares also allowed counter-remixers to appropriate their content and circulate their counter-remixes widely.3 Racist counter-remix changes the context, purpose, and audience of the media, precisely what Lillie and other family members were concerned might happen if the positive representations of Black family found in MJ content were detached from their original relationship to real people and events.

When using media to represent members of marginalized communities, context is especially important to ensure that audiences don’t project stereotypes onto them, as Claudia Magallanes-Blanco argues in her work on the production and circulation of a community-produced documentary of the Zapatista movement that sought to complicate and humanize mainstream Mexicans’ views of the indigenous peasant Zapatistas. When the documentary was shown, it was always prefaced with and concluded by commentary and discussion with the producers, journalists, or activists, who helped audiences understand how and why the film was created (Magallanes-Blanco 263). Web 2.0 posting differs considerably from Magallanes-Blanco’s curated screening example. Although posters like Harris and Richards provided context for their images using captions and directed their messages to their social media followers, counter-remixers ignored those meanings and imposed their own racist narratives on the images, recirculating the remixes to new audiences for new purposes. Like Richards and Harris, members of the Jenkins family claim authenticity for their family-based media. The remix culture theorized by Jenkins and Lessig, however, mitigates against this kind of authenticity, as Gregory and Losh point out: one of remix’s main premises is to change the context, purpose, and audience of the content it draws on. And in the cases of the fan fiction, sing-along, vidding, and reenactment texts Henry Jenkins and Lessig use to argue for the benefits of participatory cultures’ democratization of production, such creative license seems benign and even liberating. But cases of racist counter-remix bring up the kinds of human rights conflicts that Gregory (“Cameras Everywhere” 200-201) warns about: How can digital content producers navigate the contradictions between the right to freedom of expression, on the one hand, and the right to personal agency, dignity, and worth, on the other?

In addition to concerns about uncontrolled circulation, digital human rights advocacy also underscores Lillie’s concern over who owns content posted on Web 2.0 platforms. Beyond the visibility of publicly-posted Web 2.0 content (like Richards’s and Harris’s photos), even when content is made private or deleted, it persists on the servers of platform’s corporate owners. This kind of data storage enables government surveillance, seen in Gregory’s (“Human Rights” 555) example of a case in which Yahoo released content created by Chinese journalist Shi Tao when the company was subpoenaed during a government investigation and McKee’s (284-286) detailed discussion of the federal laws enabling government surveillance of online communication. Access to and control of cultural knowledge documented digitally also has other legal implications where intellectual property is concerned. In Bidwell and Winschiers-Theophilus’s work with Namibian folk healers, they encountered considerable difficulties negotiating between their own practices (informed by Namibian law) that sought to protect the knowledge of the herbal lore participants shared with them (potentially valuable as medical treatments) and participants’ investment in sharing this knowledge widely (informed by customs encouraging sharing knowledge freely with “all those who are interested”) (212).4

However, the idea that community-derived material constitutes an important source of knowledge that warrants careful management is a relatively novel one when it comes to studies of participatory culture. As Beer argues, digital labor theory posits that the content users contribute to Web 2.0 platforms like Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, and other sites (photos, video, and written posts) constitutes the material these tech companies monetize to secure their billion-dollar-plus dollar valuations. Although the Jenkins family--like most Web 2.0 users--wouldn’t expect sizable compensation from viewers, like Beer they recognize the relationship between content as unique and culturally valuable intellectual property and Web 2.0 business models. As the shared concerns of Gregory, Bidwell and Winschiers-Theophilus, Beer, and the Jenkins family highlight, placing content in the hands of Web 2.0 corporations gives them control of this material, meaning that they can use it for their own purposes or turn it over--either to investors or to the government--without users’ consent or even knowledge. And whether users’ data gets turned over or not, Web 2.0 corporations monetize such content, at least in aggregate. And as Oscar H. Gandy (131-132, 140) has noted, even when online data is released in this kind of aggregate form, simple scrutiny can often identify individual users based on triangulating factors, a risk that is heightened for underrepresented and racially marginalized users. For these reasons, turning family stories and media over to outside corporations was unacceptable to Lillie, due both to her commitment to controlling the circulation of her family’s heritage and her plans for future research. As a result, Lillie and her family were unwilling to surrender control of MJ content to Web 2.0 corporations.

Ethical Community Media Projects: Education and Design

Cases like the MJ Project highlight the risks that the practices and infrastructures of participatory culture entail. Gregory (“Cameras Everywhere”) argues that the visibility, spreadability, and permanence of material posted on Web 2.0 platforms necessitate both cultural and technological changes, focusing on informed consent as a central principle, echoing Adkins’s discussion of the contested nature of consent and consent protocols. First, Gregory recommends educating those who post and remix online digital content to consider whether those depicted agree to have their material posted online and whether they understand the risk of exposure they run when doing so (“Human Rights” 8). Based on her experience doing advocacy work through digital storytelling with marginalized women and AIDS-affected communities around the world, Amy Hill argues that consent should be revisited throughout the process of creating online texts, and that composers should be continually reminded of the exposure risks associated with the digital circulation of online material so that they can make thoroughly informed decisions about consent (25). This is especially important because, as both Gregory and Hill caution, the consequences of circulation extend beyond the content creator. They offer examples of cases where another person included in a digital story (Hill 34) or a bystander captured in the background of an activist’s video (Gregory “Human Rights” 552) without his or her knowledge or consent suffered consequences ranging from social ostracism to government persecution. “Bystander” risks aside, while it might be possible to educate specific audiences like Gregory’s human rights advocates or Hill’s digital storytellers about the ethics of creating and remixing online content, it’s hard to imagine how to promote these practices in participatory cultures at large, especially among problematic counter-remixers like the ones who appropriated Richards’s and Harris’s content. Although many media literacy initiatives include guidelines about this ethical dimension of digital content creation (see Coley for a writing studies-based example), digital composers like the racist counter-remixers who appropriated Richards’ and Harris’ content clearly don’t abide by them and the infrastructures of Web 2.0 platforms don’t require them to.

The communal process of the MJ Project’s composition highlights another issue that Gregory’s argument for media ethics training glosses over. Either educating individual content producers or prompting them to guide future remixers’ use of their material assumes that responsibility for culturally-sensitive material can be placed in the hands of individual contributors, and that existing concepts of ownership sufficiently address community-based understandings of what material should be distributed digitally and how and for what purposes it should be presented. Where Gregory and Hill position digital activists and storytellers as individuals empowered to make decisions about whether to make culturally- and personally-sensitive material public, Jason Edward Lewis and Skawennati Fragnito treat these decisions communally, describing the group discernment process they used to lead groups of indigenous artists, Native youth, and students and faculty from Concordia University’s design program collaborating on a video game called Skins, based on Mohawk myth, legend, and worldview. Whenever a new storyline was proposed, the entire group met to discuss “how the person knew the story, if other people knew it, and if anybody knew of the constraints--if any--normally imposed on the telling of it” (Lewis and Fragnito 128). This process of collective discernment mirrors the way the Jenkins family developed the content for the MJ Project and made decisions about its circulation. At face-to-face family gatherings, the family discussed the issues laid out here to make choices about their shared stories and media that reflected their sense of family identity and ownership. Their process foregrounds the social context that Gregory and Hill present as problematic, the fact that the events captured in activist media and the events recounted in family stories are full of people other than the content creator and the fact that these “supporting characters” also have the right to shape how their representation circulates. The Jenkins family and the Skins development group call for more capacious, interactive, and flexible ways of deciding what stories to tell and where and for what purposes to tell them.

In part, this tension surrounding ownership of media featuring other people is rooted in the design of Web 2.0 platforms. Applications like Facebook, WordPress, and Tumblr operate according to individual user accounts, locating control over posted content with a single user, a topic that has been discussed in technical communication in terms of managing ethos and information for organizational social media accounts (see Bowdon) rather than ethics. Fittingly, therefore, Gregory’s other recommendation for ethical digital content creation concerns working with the corporate owners of popular Web 2.0 platforms like YouTube and Twitter to change their infrastructure, adding steps to the upload process that ask posters to

- certify that they have the consent of the people depicted (“Cameras Everywhere” 205),

- obscure faces and backgrounds to anonymize people depicted (“Human Rights” 8), and

- provide information about the original context and purpose of the material to guide remixers’ use of it (“Human Rights” 7).

These proposed safeguards rely on users to self-regulate, however, and therefore can’t prevent the kind of racist appropriation about which the Jenkins family raised concerns. Infrastructural changes like this would, however, raise all users’ awareness of the ethical considerations and potential consequences of posting content online in a participatory culture, and--if framed, as Gregory advocates, in terms of universal human rights--would remind remixers potential tensions between others’ rights to personal agency, dignity, and worth, and their own right to freedom of expression. But the communal process of the MJ Project’s composition raises other issues which Gregory’s suggestions for media ethics training sidesteps, concerning the logics of sharing built into the infrastructure of Web 2.0 platforms.

Conclusion: Digital Design and Accessibility for an Inclusively Participatory Culture

In light of the problems Web 2.0 platforms pose for presenting and circulating culturally sensitive content, why use them at all for such projects? Grabill and Ridolfo, Hart-Davidson, and McLeod (“Balancing,” “Imagining”) make compelling arguments for designing independent infrastructures that allow specific communities to control everything from interface to functionality to data storage. On the other hand, in addition to the technical expertise required for this level of design, Lillie had serious concerns about whether or not such a system could capture the kind of collaborative recollection that proved most fruitful for drafting the MJ Project. Turning to Web 2.0 platforms because they were already interwoven into (at least some) family members’ communication practices, she considered Tumblr, WordPress, and Facebook as culturally and technically accessible ways for relatives to contribute to the archive of MJ’s legacy within the family. As Gregory (“Human Rights” 554) argues, this is why infrastructural changes to Web 2.0 platforms are necessary: Their accessibility has made them ubiquitous, so rather than concentrating on creating a marginal utopia governed by ethical principles of posting and circulation (as McKee calls for doing), changes need to be made to the infrastructure of the corporate platforms that dominate participatory culture to broaden the reach of ethical digital content creation.

The issue, in such cases, derives from the seeming incompatibility of a multi-optioned participatory context that allows for degrees of sharing specified not in design, but in use. This idea asks whether it’s possible to design digital community texts for sharing according to participants’ specific expectations for circulation and design. This would require more than just choosing levels of privacy or giving unknowing consent to privacy waivers buried deep in user agreements. Such a multi-optioned scenario does not exist in the current social media environment. As the Jenkins family’s decision process illustrates, current Web 2.0 options fail to provide the balance needed between protecting rich heritage resources from misappropriation and extending flexible and robust sharing features to community members.

As such, the experience of the Jenkins family shows how expanding digital composing’s audiences and number of participants raises questions that existing infrastructures of Web 2.0 platforms do not yet adequately address. As the MJ Project illustrates, communities of color are integrating robust and longstanding literacy practices and values into digital technologies, but their concerns--especially about content control and circulation--highlight access issues and design critiques that widely-used Web 2.0 platforms like Facebook, Tumblr, and WordPress fail to address. As Kimberly Christen has argued in asserting the need for digital archival platforms built according to indigenous worldviews that run counter to the conventional digital wisdom of unfettered circulation by instead limiting access according to cultural knowledge and artifact context:

[P]reservation and access are their first priority, while the social life of the objects is secondary, if considered at all. [They] begin with the premise that all information should be open and dissectible into bits and bytes for transmission. What we [Christen and her Australian Aboriginal colleagues] wanted instead was an archive and search engine whose primary goals were not preservation and universal access, but respect for the dynamic social and cultural systems, relationships and cultural protocols within which information is embedded. (5)

However, Christen (like Ridolfo, Hart-Davidson, and McLeod) is creating an archive, rather than an everyday tool that would also function as a means of regular communication and community building.5 This is where Gregory’s emphasis on the mundane ubiquity of familiar Web 2.0 platforms becomes important: These platforms are influential and widely used venues for communication and community building, but they aren’t inclusively designed in terms of the ideologies that define their uploading, sharing, and data control policies. As is often the case, marginalized communities’ specific concerns make visible and problematize the assumptions woven into these platforms’ designs.

As Melanie Yergeau (“Disabling Composition”, “Reason”) argues with regard to disability and digital design, accessibility can’t be an afterthought, a bandage applied to a design that was created while ignoring the needs of diverse users. Design--or in this case, the kind of structural design revision Susan H. Delagrange discusses--should reflect the cultural dimensions of accessibility Porter and Yergeau discuss, including the kinds of visibility and shareability protocols Christen and the Jenkins family call for, while retaining insofar as possible the kind of community-building and in-group sharing that have made Web 2.0 platforms so popular and powerful. This will diversify the design of digital participatory culture in meaningful ways and move beyond simplistic understandings of the digital divide and access. As seen in the Jenkins family’s process of composing and planning for the MJ Project as a digital text, African American communities are uniquely positioned to identify ideological dimensions of design, that, if addressed, would change the infrastructure of the Web 2.0 platforms millions of people worldwide use on a daily basis.

Coda: Lillie Reflects and Advises on Family History Research and Teaching

My reflections are two-fold: I speak as someone who is called a family historian, and I speak as a researcher sharing post-research findings. My comments may be taken as lessons learned and as best practices in both capacities.

“Family historian” is a title I never wanted, and had I known that MJ was in the process of conferring that office, I might have opposed the appointment. The process of becoming family historian, at least in my case, was not a choice I made but rather a role for which MJ chose me because I was inquisitive. Photography has been one of my hobbies since my teen years, so I always looked at our family in the way of making records of our lives at special occasions, family gatherings, and even during mundane daily activities. I asked about and wanted to record our family’s life from all angles. I wanted to know so much. I even asked an elderly great-aunt about the “old days” as when I was a teenager. She told me she would rather not speak about them. That didn’t stop me thinking or asking others. MJ always told us stories about our family, so anyone from my sibling group might have been her designee, I suppose.

I didn’t ask MJ about our family’s life in a systematic way until I became engaged to be married. At that point, the prospect of having my own children became more real, and I anticipated telling them about their forebears. I bought a book that had sections to complete on significant members and events. I asked MJ to complete as much as she could recall about our family’s history. When she finished her bit, I gave the book to my fiancé and asked him to do the same with his family. I think that was when MJ started to tell me about our family’s background in earnest.

In my zeal, I visited the National Archives in Washington DC to flesh out the recorded details of our family’s historical lives. I have a degree in librarianship, so I’m no stranger to organizing and storing information for retrieval and future use. I recall reporting to MJ one of my findings: Census records showed that many of our ancestors’ names were taken from the Bible. That was the first time I thought, after our conversation, about how much information MJ was sharing with me. I needed to write it down if I hoped to remember all of it.

Over the years, I took photos to document family history. After showing an interest in our history, and having MJ pour out information, I started recording family history in writing. All of MJ’s children and some of her grandchildren have a store of family folklore, no doubt. We’re that kind of storytelling family. To my knowledge, however, only I set out to capture those stories and then to seek out more historical documentation to verify the “tellings.” I sort of awakened to the fact that I was acting out the duties of our family’s historian.

So, what have I, the family historian, to share about the process of researching and writing the book about MJ? Here’s a brief list of my thoughts on best practices that instructors or anyone interested in recording their family’s history might use.

Family history best practices

- Select meaningful topic(s). Start by asking about what is important to you as a student/inquirer/interviewer/researcher. Although I’d always had an interest in our family’s folklore, my impending marriage found me projecting several years into the future. I wanted more information so that I might pass it along to my own offspring.

- Consider your personal interests. Why do you want more information about your family? Start with self-reflection. Write/ruminate/cogitate/speak about your own story as a member of your family and community.

- What interests you about the “characters” you know in your family? Is there a common hobby/skill/interest they share? Is there a particular color of hair or way of speaking/walking/thinking shared by several family members, even in different generations? Did your family relocate from a different city/state/nation/planet, and are you curious about that? Are there family tales that interest you about some trait that came to you from the paternal (or maternal) side of your family? Which languages do your family members speak other than English? Is there a current or deceased member of your family who is famous or lays claim to connections with the larger city/state/regional/national/international historical context?

- Keep a watchful eye on the scope of your project. Nothing is as frustrating as realizing you have become inundated with ”useful stuff,” but lack the resources of time, interest, or knowledge to corral the lot and make sense of it.

- Start with small bites. Maybe you want to start by looking only at one side of your family tree. Outline several mini projects or chapters rather than attempting to write an entire family history all at once. Is there a decade or event in the family’s life that is of particular interest to you?

- Be realistic about the amount of time you have to spend and the amount of information you can reasonably acquire and use for the project you lay out.

- Assess the amount of time, energy, and financial resources you have to dedicate to the project you choose.

- Plan a budget for your project and stay within it.

- Form realistic timelines given what you want to accomplish.

- Be generous with yourself and forgiving of yourself when/if you run out of resources for the grand project you’ve planned, allowing yourself to redefine it and maybe limit its scope.

- Involve other family members in your project.

- Let family members become as involved as they want to be, acknowledging their particular efforts and contributions. Some family members may immerse themselves in the project, while others may be content to receive intermittent updates on your progress. Be OK with that.

- Develop a loose outline or description of your project to share with your family when they ask, to pique their curiosity. This will also help you define your project’s scope and give you some handy talking points. The description might contain a set of questions you can share with your family, so they’ll be prepared when you interview them. Word your descriptions and questions in such a way that family members will feel free to volunteer information.

- Ask elderly relatives for permission to look at family pictures that are in their possession. It will be a lot more fun if you make the sifting process a mini project.

- A good time to do this may be when a grandparent or other relative is moving to a smaller dwelling. Do this soon after you hear about the relocation. That way, your relative will be relaxed and grateful for someone to help clear out old belongings in a meaningful and non-threatening way. This will help that person, and you may find that he or she is willing to part with certain items and share more stories because you show an interest and she or he has time. This is also a great bonding exercise.

- Ask your relatives if you can help them make scrapbooks. Buy a couple of albums and take them with you so you can produce mementos of your visits. That will make them more likely to open up personal archives (and tell you oral history). This may be a good idea if you know your relatives don’t have an organized system for family mementos—if you want to revisit the same venue, the process will be that much easier the second time around, since you’ve helped organize the information and you’ll be familiar with the system. So go ahead, volunteer to climb up to reach the photos stored on the top shelf of the closet; crawl under the bed or into that dusty attic or storeroom to retrieve the boxes the person points out. Wear old, comfortable clothes and shoes--things you don’t mind messing up. Don’t forget to carry your phone, camera, laptop, and recorder. Do remember to take along extra memory cards or batteries!

- Find out if anyone in your family kept a journal, a diary, or wrote a book or letters you may read to get a sense of the background or even details of the family’s life.

- Talk with people in your family’s hometown who are not related to you (neighbors, coworkers, civic and religious affiliates, childhood friends). They can be a rich source of information family members may not have. Also, this will often provide a different perspective on the family and its history.

- Conduct formal research. Cheer up! No one’s consigning you to the catacombs! It sounds as if I’m advocating spending hours sitting in a library or dusty archive. While it may very well come to that depending on your project, start with some things a bit less daunting and intimidating.

- Sift through your family’s photo albums. You can take this on alone or with siblings or parents if the albums belong to your immediate family — to your parents or grandparents.

- Consider planning a family function that includes time spent looking at family photos. Why not organize a fun activity and gather family stories at the same time by featuring a photo contest based on the oldest wedding photo, the most unusual baby photo pose, or the funniest facial expression in a baby picture? Every participant will get a charge from this type of structured multigenerational activity.

- The next steps may involve the kind of research most people would rather not do: leg work.

- If your family members are/were politically or socially active, newspaper articles may be a good source of information.