#BlackLivesMatter: Tweeting a Movement in Chronos and Kairos

Introduction

The night George Zimmerman was acquitted for the murder of Trayvon Martin, the news was announced on most major networks. Soon after the announcement, Sybrina Fulton, the mother of Trayvon Martin, changed her Twitter account’s avatar to a solid black. Within minutes of her visual articulation of grief, sadness, and anger, thousands of her Twitter followers and supporters followed suit. Since the Zimmerman trial, African American activists on Twitter have used this form of social media as a virtual headquarters for a movement against police use of excessive force. While George Zimmerman was not a policeman, the perception of a disregard for black bodies by the overzealous, the fearful, and the “out of control1” is supported by “Stand Your Ground” laws and police policies codified within this country’s centuries-old institution of racism. Yes, we have had an African American President who often reminded us that “we are a nation of laws,” but he also acknowledged the legacy of institutionalized racism-racism that has persisted despite his having been elected twice.

Some of us did not know what these “vestiges” of racism looked like in the 21st century until we digested months’ worth of videos that appeared to be obvious evidence of use of excessive force. Over the past year, I have used Twitter as more than simply a space to receive updates on new restaurants, films, and music incognito and with little interaction. My experience on Twitter changed when I decided to follow African American activists in the #BlackLivesMatter movement, which was founded by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi. I began to follow the Ferguson, MO activists who spent much time informing their followers and those who read their tweets or retweets of police shootings of unarmed black women and men. Even in my infrequent use of Twitter, I am often inundated with news or videos that look like police abuse or killing of a person of color. I argue not about whether these people of color are innocent or guilty, but that they are unarmed and dead.

My Twitter timeline also includes much debate from a racially diverse constituency of Twitter users who spend much of the day defending all police practices even after the police are indicted, turn themselves in, or apologize for their actions. Teachers, social workers, members of the armed forces, religious leaders, politicians, the police, and other public servants abuse power and demonstrate incompetence. This is not an indictment of all members of these organizations, most of whom perform their jobs with professionalism and integrity, but it is an indictment of those who do not. When videos of perceived instances of excessive use of force by police are recorded for all to see and shared on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, they go viral. I submit that these shared videos are not examples of black people “playing the race card” or “race baiting,” phrases that are often used defensively when there is mention of race or racism. Black people in this country have a strong group political identity based not on a history of telling untruths or “race baiting,” but instead on a history of documented legal discrimination. The findings of a June 18, 2015 Amnesty International report, Deadly Force: Police Use of Lethal Force in the United States, state;

As a passive user of Twitter, I read more tweets than I write. Over the past few months, I have witnessed the emergence of African American activists who use Twitter to share news of the cases highlighted in the Amnesty International report. In this chapter, I discuss the use of Twitter as a space for a unique movement against the excessive use of force by police within the United States. I attempt to illustrate how social media activists have effectively formed a movement that is quite different from the U.S. Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, part of which was beautifully interpreted by film director Ava DuVernay in the 2014 Oscar-nominated historical drama Selma. Selma is an artistic interpretation of the three protest marches from Selma, AL, to Montgomery, AL, that preceded President Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In a video interview regarding her participation in Selma, billionaire philanthropist and media mogul Oprah Winfrey discussed the strategic nature of the Selma marches in relation to the Ferguson protests, stating, “I think it’s wonderful to march and to protest, and it’s wonderful to see all across the country, people doing it, but what I’m looking for is some kind of leadership to come out of this to say, ‘This is what we want. This is what we want. This is what has to change, and these are the steps that we need to take to make these changes, and this is what we’re willing to do to get it.’” (People.com, “Oprah Winfrey’s Comments…).

Those of us who read the tweets of DeRay Mckesson and Johnetta Elzie had some idea of the movement’s demands, but these demands were articulated for a much broader audience in a New York Times article, “Our Demand Is Simple: Stop Killing Us,” which prominently displayed images of Mckesson and Elzie sitting and reading from their MacBooks. In this article, Jay Caspian Kang writes, “Mckesson’s tweets were usually sober and detailed, whereas Elzie’s were cheerfully sarcastic, mock-heroic and forthright: a running account of events that felt intimate.” Kang’s description of the activists’ tweets was accompanied by Mckesson’s tweeting process. Kang wrote, “As we drove from Montgomery to Selma, Mckesson wrote drafts of tweets on his phone. ‘I do this to make sure what I say can be tweetable,’ he explained. ‘And it helps me be precise in what I say.’ He muttered lines to himself. ‘We must always confront,’ he said, but something about the phrase displeased him. He deleted the words and started from the top.” This study does not purport to analyze the writing processes of activists in the construction of tweets, but aims to highlight the importance of this space and genre of writing to an evolving social justice movement. I conduct discourse and descriptive analyses of the tweets associated with the hashtag most closely aligned with this movement, #BlackLivesMatter, described by its founders as follows:

Methodology

While most of us have viewed the video recordings that many argue are evidence of use of excessive force by police, few scholars in English Studies have examined the tweets associated with this hashtag as a form of empirical data. In Melody Bowdon’s article “Tweeting an Ethos: Emergency Messaging, Social Media, and Teaching Technical Communication,” she collaborated with students to code tweets during Hurricane Irene. Bowdon states: “…[T]here are many models of coding tweets, ranging from strictly quantitative approaches that count instances of various types of posts to epidemiological/infodemiological that can offer public health officials opportunities to intervene and address public health concerns and misinformation (Bowdon 43.) Like Bowdon, I am interested in the types of rhetorical moves in the tweets, but this study will couple textual analysis with some quantitative analysis in an effort to identify rhetorical moves as well as their frequency. Since the majority of those tweeting with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter are not public figures or institutions, I chose not to focus on the writers of the tweets or individual tweets. Instead, I conduct a quantitative analysis of a day’s worth of Top Tweets under #BlackLivesMatter to provide a rich description of how this hashtag is employed across hundreds of users. Top Tweets are identified by a Twitter algorithm and consist of tweets that have been favorited, retweeted, or responded to in some manner by other users. Therefore, a discourse analysis of #BlackLivesMatter Top Tweets involves tweets that others were reading and engaging with on some level on the date I accessed them. As more users reply to, favorite, or retweet tweets made on any particular day, the makeup of Top Tweets for that day may change or expand. Therefore, I selected Top Tweets with the intention of carving out a manageable chunk of data for the purposes of this analysis.

By focusing on the content of the tweet instead of the user, the anonymity of those tweeting under this hashtag is protected. This is important because I realize that my role as participant observer does not give me membership in Twitter communities shaped by hours of daily interaction and virtual conversations, which I avoid as researcher and an infrequent user of social media. I argue that Twitter is an effective space through which to better understand the rhetorical contexts of conversations qualitatively at any particular time and quantitatively over time. In other words, Twitter is effective in capturing this current movement in chronos and kairos.

Discourse Analysis

I am interested in identifying recurring themes of tweets associated with #BlackLivesMatter on a given day. To limit the scope of the study, I examined Top Tweets under #BlackLivesMatter as provided by the Twitter algorithm on July 6, 2015, the date I accessed the tweets. Initially, my rationale for selecting June 27, 2015 was based on the fact that this date falls on a Saturday between two significant holidays celebrated throughout the U.S., June 19 (Juneteenth) and July 4, both of which celebrate events related to liberty and independence. As a researcher, I was unaware that the day before my selected date of analysis, June 26, would present significant events related to race relations and issues of equality: 1) the funeral of Rev. Clementa Pinckney, the pastor of Emanuel AME Church and South Carolina state senator who was gunned down a week earlier with eight of his parishioners in a racially motivated massacre during Bible study, 2) the passion-filled eulogy for Senator Pinckney given by President Barack Obama, and 3) the announcement of the Supreme Court decision in support of gay marriage in the U.S. A cursory analysis of #BlackLivesMatter on June 26 showed that the conversation under this hashtag was heavily influenced by #LoveWins, a hashtag that voiced solidarity with the Supreme Court’s decision on marriage equality, as well as many comments regarding Senator Pinckney’s funeral and President Obama’s eulogy, which concluded with a rendition of Amazing Grace. I anticipated that continuation of these spirited discussions on June 27 would also include the broad range of recurring themes that I observed in prior readings of #BlackLivesMatter tweets.

The hypothesis was that #BlackLivesMatter was used for a variety of purposes that defined a movement that now extended well beyond discussions of excessive force by police. Before the events of June 26, I constructed a research design. In my examination of press conferences, interviews, news articles, and social commentary following the deaths of Mike Brown in Ferguson, MO, Eric Garner in Staten Island, NY, and Walter Scott in South Carolina (all of whom were killed by police), I observed Twitter users engaging in critiques of police and institutions (e.g. government agencies, the judicial system, mass media) and in debates with opponents of the #BlackLivesMatter movement. From these sources I employed grounded theory, which at its best requires identification and rigorous coding of recurring themes as understood by the researcher, to develop a list of discourse markers to be used to conduct a discourse analysis of tweets under the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag. I anticipated that common rhetorical moves would fall into the following categories:

- Critique of news media

- Critique of prosecutors and district attorneys

- Critique of governors and state officials

- Critique of police

- Critique of city officials

- Critique of the FBI

- Critique of the Department of Justice

- Critique of the Obama Administration

- Debate with those following advocating the #AllLivesMatter perspective

- Debate with those who did not view these incidences as use of excessive force by police

- Debate with those attempting to deflect/troll the conversation

- Debate among Black Lives Matter activists

- Debate with journalists

- Sharing of news articles

- Sharing of government reports

- Sharing of statistical data from research institutes and non-profits

- Sharing of videos depicting examples of use of excessive force

- Sharing of interviews with families of victims of use of excessive force

- Legal commentary

- Emotional release and/or expressions of anger, frustration, sadness, and despair

Of course, there were many significant events following the initial analysis, including 1) the racially motivated massacre of nine members of Emmanuel AME church in Charleston, SC, and the subsequent debate regarding the removal of the Confederate flag and related statues; 2) President Obama’s eulogy, which included a powerful discussion of race; and 3) the Supreme Court’s decision on marriage equality. After I conducted a rhetorical analysis of all 174 consecutive #BlackLivesMatter Top Tweets that I accessed on July 6, the following categories emerged:

- Sharing of articles, data, or reports documenting excessive use of force by police

- Criticism or praise of the media

- #BlackLivesMatter solidarity with #MarriageEqualitiy

- Criticism or praise of government agencies or elected officials

- Solidarity with #BlackLivesMatter

- Updates on #BlackLivesMatter protests, events or related acts of civil disobedience

- Negative critiques of #BlackLivesMatter

- Sharing of quotes, music, film, and other historical information related to civil rights movements

- Derailment: black-on-black crime, #AllLivesMatter, and other “more important” problems

- Ad hominem attacks on blacks

- Ad hominem attacks on other racial or ethnic groups

- Sharing of examples (textual or visual) of racism, including racially motivated violence

- Sharing of examples (textual or visual) of excessive use of force by police

- Sharing of examples (textual or visual) of misogyny

- Commentary on mass incarceration in the U.S.

- “Legalize Black”: Commentary (textual or visual) on racism in the aftermath of SCOTUS decision on marriage equality

- Criticism or praise of corporations

- Sharing of resources or commentary on white privilege

While some categories from the early stages of this study were revised or collapsed to better describe the observed text, others were removed entirely because there were no obvious examples in the June 27, 2015 data. The observed tweets were each coded as falling into one category; tweets were coded as “1” for observed use of the categorized rhetorical move in each selected tweet and as “0” for lack of observed use of the categorized rhetorical move in each selected tweet. Some tweets were indecipherable or no longer available, and these were and coded into a separate “uncategorized/unavailable” category.

Quantitative Analysis

For the quantitative analysis portion, descriptive data via frequency distributions allowed systematic analysis of all #BlackLivesMatter Top Tweets over the course of a day. The selected tweets surrounding selected events represent categorical-level data, and use of frequency distributions provide a numerical description of the recurring themes tweeted under #BlackLivesMatter. While a chi-square test or crosstab analysis of these tweets with special attention to users’ identity (race, ethnicity, gender, age, location and profession) might also have been useful, this information would have had to be retrieved from users via some data-collection tool. An analysis of Twitter users’ avatars, photographs, and tweets is not reliable in identifying how a person self-identifies or other demographic data.

At its foundational level, Twitter can be described as conversations conversations that span various times and places. The #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, public participation in a conversation surrounding a movement that sparked a number of comparisons to the U.S. Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, is an immediate means by which interested individuals can connect, share, and organize information related to current events. The resulting conversations that help increase the use and visibility of #BlackLivesMatter and the subsequent civil rights movement lie on a continuum.

A cursory review of the tweets including the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag shows that they vary day by day, moment by moment, and tweet by tweet. When reviewing the Top Tweets tagged by any particular hashtag, the accompanying tweets and resultant findings are necessarily affected by the sequence of moments (chronos) that precede and follow the event(s) that sparked the creation of the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag. With the use of categorical level data contained within the “Top Tweets,” frequency distributions surrounding the categorized rhetorical moves provided a systematic method of organizing the data as well as a visual and numerical description of the identified rhetorical strategies used on this day involving the selected hashtag.

Results and Implications

Today, we have access to many cultural artifacts that help us better understand the U.S. Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. I argue that tweets provide future researchers, teachers, students, and activists with the historical context that defines today’s social media-mediated civil rights movement. We are not naive enough to believe that activists share all of their opinions or strategies in this public arena, but we are privy to their conversations with the public and clarifications and discussions of short- and long-term objectives and goals. The following tables summarize the findings of a discourse analysis of tweets from Twitter users, most of whom I believe do not identity activists. As far as I could surmise without conducting interviews or surveys, the majority of the tweets I analyzed were created by Twitter users who either supported or disagreed with the #BlackLivesMatter movement and simply made comments or shared information with their followers. (See Table 1: Frequency Distribution of #BlackLivesMatter Top Tweets on June 27, 2015.)

| Discourse Markers/Categories | Total Number (N=174) | Frequency Percent |

| Sharing articles, data, or reports documenting excessive use of force by police | 8 | 4.6% |

| Criticism or praise of the media | 2 | 1.1% |

| #BlackLivesMatter solidarity with #MarriageEquality | 5 | 22.9% |

| Criticism or praise of government agencies or elected officials | 14 | 8% |

| Solidarity with #BlackLivesMatter | 19 | 10.9% |

| Updates on Black Lives Matter protests, events or related acts of civil disobedience

|

31 | 17.8% |

| Negative critiques of #BlackLivesMatter | 13 | 7.5% |

| Sharing of quotes, music, film, and other historical information related to civil rights movements | 12 | 6.9% |

| Derailment: black-on-black crime, #AllLivesMatter, and other “more important” problems | 20 | 11.5% |

| Ad hominem attacks on blacks | 3 | 1.7% |

| Ad hominem attacks on other racial or ethnic groups | 0 | 0 |

| Sharing of examples (textual or visual) of racism, including racially-motivated violence | 10 | 5.6% |

| Sharing of examples (textual or visual) of excessive use of force by police | 9 | 5.3% |

| Sharing of examples (textual or visual) of misogyny | 4 | 2.3% |

| Commentary on mass incarceration in the U.S. | 2 | 1.1% |

| “Legalize Black”: Commentary ((textual or visual) on racism in the aftermath of SCOTUS decision on marriage equality | 5 | 2.9% |

| Criticism or praise of corporations | 4 | 2.3% |

| Sharing of resources or commentary on white privilege | 2 | 1.1% |

| Uncategorized (i.e., meaning indecipherable or no longer available) | 11 | 6.3% |

Table 1: Frequency Distribution of #BlackLivesMatter Top Tweets on June 27, 2015.

As expected, there was a broad range of discussions on this day, which I describe in more detail in Table 2 (Summary of #BlackLivesMatter Top Tweets on June 27, 2015). Although the tweets varied in purpose and content, whether they were written directly or indirectly, the majority of Twitter users tweeting using this hashtag at that particular moment were addressing issues that fell under the mission of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, part of which I quoted earlier. (See http://blacklivesmatter.com/about/).

| Discourse Markers/Categories | Summary of Tweets |

| Sharing articles, data, or reports documenting excessive use of force by police | These tweets included references to articles that supported arguments that excessive use of force by police is a problem, especially as it relates to African Americans. |

| Criticism or praise of the media | There were two tweets, one positive and one negative, regarding media coverage of these issues. |

| #BlackLivesMatter solidarity with #MarriageEquality | These tweets expressed solidarity with and support of the Supreme Court’s decision on marriage equality. |

| Criticism or praise of government agencies or elected officials | While there were a couple of negative tweets about city and state government officials, the overwhelming majority of these tweets praised President Obama for his eulogy speech, which many viewed as his most comprehensive discussion of race and racism since taking office. |

| Solidarity with #BlackLivesMatter | These tweets varied in content, but their aim was to express support and solidarity with #BlackLivesMatter. |

| Updates on Black Lives Matter protests, events, or related acts of civil disobedience

|

While this section included some remarks about local #BlackLivesMatter events, the majority of these tweets discussed the details of Bree Newsome, an African American woman, artist, and activist who ascended the South Carolina State House flag pole and removed the Confederate flag in an act of civil disobedience. This was most prominently discussed on the same day under the hashtag #FreeBree, which trended that day on Twitter. |

| Negative critiques of #BlackLivesMatter | TThere were many negative critiques of the #BlackLivesMatter movement from those who, for various reasons, did not support civil rights protests or calls for an end to the use of excessive force by police. |

| Sharing of quotes, music, film, and other historical information related to civil rights movements | Users made comments regarding Martin Luther King Jr. and Nina Simone and shared quotes, music, and historical documents regarding previous civil rights movements. |

| Derailment: black-on-black crime, #AllLivesMatter, and other “more important” problems | The “All Lives Matter” sentiment, which many view as a form of derailment, was voiced. Other tweets that fall in this category raised questions about “black-on-black crime,” which is an entirely different problem, that will require different solutions. |

| Ad hominem attacks on blacks | There were examples of name-calling and one racial slur. |

| Ad hominem attacks on other racial or ethnic groups | There was no evidence of name-calling or racial slurs.

|

| Sharing of examples (textual or visual) of racism, including racially-motivated violence | There were a range of discussions of racism and some mention of the racially-motivated murders of nine members of Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, SC. |

| Sharing of examples (textual or visual) of excessive use of force by police | These comments were about specific cases and experiences that users presented as examples of excessive use of force by police. |

| Sharing of examples (textual or visual) of misogyny | There were instances in which users referred to misogyny in the black community and in general. |

| Commentary on mass incarceration in the U.S. | These comments were about the “prison industrial complex” and issues of mass incarceration of blacks in the U.S. |

| “Legalize black”: commentary (textual or visual) on racism in the aftermath of SCOTUS decision on marriage equality | These comments, which were a reaction to the Supreme Court’s decision on marriage equality, continued from the previous day. The comments used the language “legalize black” or similar arguments for some contemporary triumphs in the courts and legal system for black people. |

| Criticism or praise of corporations | While one tweet praised a corporation for support of #BlackLivesMatter another tweet criticized a corporation for a perceived lack of support. |

| Sharing of resources or commentary on white privilege | There were instances in which users share resources on white privilege. |

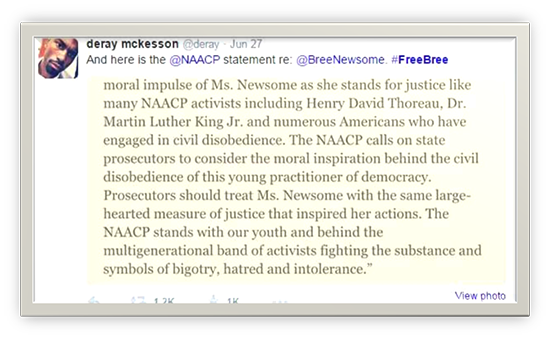

Although the Twitter users were not analyzed, I observed that few, if any recognizable leaders in the current movement used #BlackLivesMatter on June 27, 2015. A quick Twitter search of a few of the activists’ accounts reveals that they were actively spreading news regarding Bree Newsome, another activist, who removed the Confederate flag from the South Carolina State House. See two examples of tweets by DeRay Mckesson on June 27, 2015.

Notice that the first example tweet from DeRay Mckesson uses the hashtag #FreeBree, which trended on this particular day; this tweet spoke to the urgency of events of the moment. Other tweets by Mckesson on June 27 were, of course, related to the movement, but did not include hashtags since hashtags, are not always useful or necessary.

The analysis of June 27, 2015 tweets yielded interesting discussions surrounding race, racism, and efforts to dismantle discriminatory policies and symbols of white supremacy. Still, this study obviously missed an opportune moment to capture discussions of police brutality or excessive use of force by police when interacting with unarmed people of color. Substantive tweets that address these issues in detail are commonly discussed using the hashtag and the first and last name of the person killed or harmed. For example, following the July 15, 2015 death of Sandra Bland, a black woman found hanged in a Waller County, TX jail cell after being stopped for failing to signal when changing lanes and then aggressively arrested by a Waller County law enforcement officer, Twitter ignited with tweets that included the hashtag #SandraBland. Many Twitter users accompanied their tweets with #SayHerName, a hashtag often used to acknowledge police brutality and profiling of black women, a group often forgotten in discussions of use of excessive force by police. Many of these cases are documented in the African American Policy Forum’s “Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women” report (http://www.aapf.org/sayhernamereport/).

It was, by chance, the right moment to conduct a close reading of reactions to Bree Newsome’s activism as well as lingering conversations regarding the Supreme Court’s decision on marriage equality and reactions to President Obama’s eulogy of South Carolina Senator Clementa Pinckney. It was also interesting to see Twitter users attempt to derail or repurpose the use of a hashtag due to disagreement with the cause it represented. More fruitful discourse analyses of discussions in Twitter and similar spaces might be coupled with surveys or interviews with users with or without emphasis on a particular hashtag. Hashtags evolve in purpose and application and do not limit the reach or scope of the social movements they initially name. While hashtag #BlackLivesMatter is the name associated with the initial conversation, the movement against excessive use of force by police is now supported by many organizations and politicians with the power to implement the movement’s call to action. For example, 2016 Presidential Democratic Party candidates Senator Bernie Sanders and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton both publicly proclaimed “Black lives matter” in campaign speeches and ensured that the Democratic platform proposed de-escalation strategies, body cameras, and “appropriate use of force” in interactions between police and members of the public. (Democratic Platform)

Almost a year after my discourse analysis of #BlackLivesMatter tweets, I observed a televised, national conversation started by the #BlackLivesMatter and Ferguson, MO, movement during the Democratic National Convention of July 2016, which nominated the first woman, Hillary Clinton, to represent the party in the Presidential election. During this convention, President Barack Obama, former President Bill Clinton, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and “Mothers of the Movement,” a group of African American women who had lost their children in interactions with police and vigilantes, spoke about the fears African American men and women had in their interactions with the police as well as the dangers of police work. The final night of the convention included “Stronger Together: Tribute to Fallen Law Enforcement Officers,” in which parents and spouses of officers killed in the line of duty spoke about their loved ones’ commitment to those they served. High-level, national conversations about excessive use of force and the dangers faced by police were expected at this convention because in this same month, July 2016, lone African American snipers targeted and assassinated groups of police in Baton Rouge, LA, and Dallas, TX. Dallas and Baton Rouge police officers were killed in what appeared to be hate-motivated responses to recent videos showing police killings of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge and Philando Castile in Falcon Heights, MN. In the incident in Dallas, the five fallen officers were attacked from behind by an assailant while police were protecting protesters marching against excessive use of force. At this point, the movement against excessive use of force by police is accompanied by calls for respect for the dangerous nature of police work and reconciliation between police and the communities they serve. The hashtag #BlackLivesMatter may have started the conversation about de-escalation and standards for use of force, but measurable change will require police training initiatives and policy-making decisions to build trust between those who protect and serve and those whom they protect.

Works Cited

African American Policy Forum. Report. “Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women.” African American Policy Forum. Web. 4 November 2015. (http://www.aapf.org/sayhernamereport/)

Amnesty International. “Deadly Force: Police Use of Lethal Force in the United States.” Amnesty International USA, June 18, 2015. Web. 15 July 2015. (http://www.amnestyusa.org/research/reports/deadly-force-police-use-of-lethal-force-in-the-united-states)

BlackLivesMatter.com. “About Us.” Blacklivesmatter.com. Web. 15 July 2015. (http://blacklivesmatter.com/about/)

Bowdon, Melody A. “Tweeting an Ethos: Emergency Messaging, Social Media, and Teaching Technical Communication.” Technical Communication Quarterly 23.1 (2013): 35-54.

Democratic Platform. “2016 Democratic Party Platform DRAFT,” July 1, 2016. Web. 29 July 2016. ( https://www.demconvention.com/wp- content/uploads/2016/07/2016-DEMOCRATIC-PARTY-PLATFORM-DRAFT-7.1.16.pdf )

Kang, Jay Caspian. “‘Our Demand Is Simple: Stop Killing Us.’” The New York Times. The New York Times, 09 May 2015. Web. 15 July 2015. (http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/10/magazine/our-demand-is-simple-stop-killing-us.html?_r=0)

Lopez, Rebecca, and Marie Saavedra. “McKinney Police Chief: Eric Casebolt Was ‘Out of Control.’” KHOU. 10 June 2015. Web. 15 July 2015.

Mckesson, DeRay (DeRay). “And here is the @NAACP statement re: @BreeNewsome. #FreeBree” 27 June 27, 2015, Tweet.

---. “& here is the video of the Confederate Flag being removed in South Carolina today by @BreeNewsome and team.” 27 June 2015, Tweet.

PeopleStaff225. “Oprah Winfrey’s Comments about Recent Protests and Ferguson Spark Controversy.” People.com. People magazine. 01 Jan. 2015. Web. 15 July 2015. (http://www.people.com/article/oprah-winfrey-david-oyelowo-selma-protests-ferguson)

Author Bio

Miriam F. Williams, Ph.D., is a professor of English and the director of the M.A. in Technical Communication program at Texas State University. Her publications include the coauthored textbook Writing for the Government, part of the Allyn & Bacon Series in Technical Communication, and her monograph From Black Codes to Recodification: Removing the Veil from Regulatory Writing, part of Baywood’s Technical Communications series. In 2014, she coedited Communicating Race, Ethnicity, and Identity in Technical Communication for the Baywood Technical Communications series, and she coedited a special issue of the Journal of Business and Technical Communication on race, ethnicity, and technical communication in 2012.