[heavily processed ambience, echoes of interactions with the environment, especially striking different objects; fog horn in the distance]

(Thumbnail Source: Photo by Milena Droumeva)

Start by listening to the sounds of your body while moving. They are closest to you and establish the first dialogue between you and the environment. If you can hear even the quietest of these sounds you are moving through an environment which is scaled on human proportions. In other words, with your voice or your footsteps for instance, you are "talking" to your environment which then in turn responds by giving your sounds a specific acoustic quality. (Westerkamp, 1974, n.p.)

The mandate of our courses is to introduce students to the practice of listening, to help them build a vocabulary about sound, and to attune their reflective thinking about subjective experience with sound in relation to wider cultural and sociopolitical structures. Students learn both theory and terminology related to acoustics, auditory perception, orality, communication, sound in the built environment, noise measurements, and urban soundscape design. Some notable methods developed by R. Murray Schafer (1977/1994) for "resetting" the ear involve removing and then adding a sensory modality back in order to generate contrast in everyday experience (e.g., using earplugs or a blindfold). In the same vein, a soundwalk provides contrast to habitual experience by inviting an active rather than passive attending to the soundscape whilst moving through typical and sometimes familiar surroundings. In pedagogies inspired by Eastern philosophy, this kind of practice would strive to cultivate a beginner's mind (Hua, 2012), a kind of wonder and curiosity about the familiar that can help de-normalize established conventions. This reflexivity and growing toolbox of sonic sensibilities is encouraged by weekly journaling.

One of the foundational practices in the tradition of acoustic ecology is the soundwalk. A soundwalk is an organized silent group walk with the purpose of paying specific attention to sonic experience while moving through space (Westerkamp, 1974). The soundwalk has a leader who creates (usually ahead of time) an itinerary and leads the group. No one is allowed to speak until the soundwalk is over. Sometimes, the leader stops in a particularly aurally rich location and lets the group absorb the soundscape and reflect on it. For those experiencing a soundwalk for the first time, this exercise quite often results in a kind of "opening" up to the sounded environment and a reflexivity of one's sonic positionality. While soundwalks can have many variations—for example, they may incorporate performance or interactivity, hidden music or spoken word—some trusty principles stand out as universally important:

All photos by Milena Droumeva.

Below is a 2011 Vancouver New Music series soundwalk generated via the app RJDJ, which creates live filtering and mixing of acoustic sound:

[heavily processed ambience, echoes of interactions with the environment, especially striking different objects; fog horn in the distance]

(Thumbnail Source: Photo by Milena Droumeva)

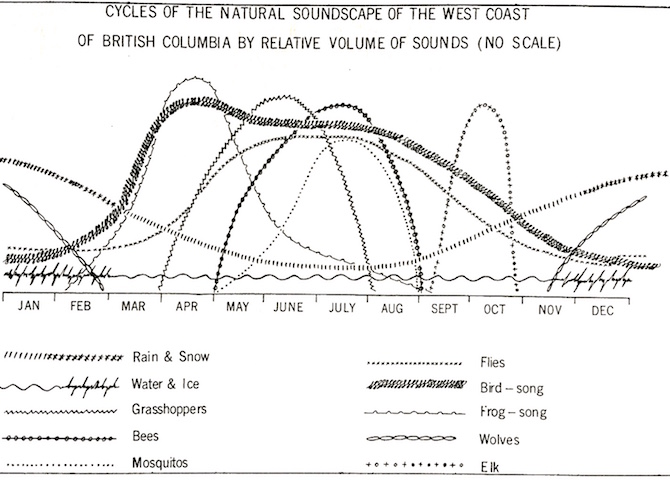

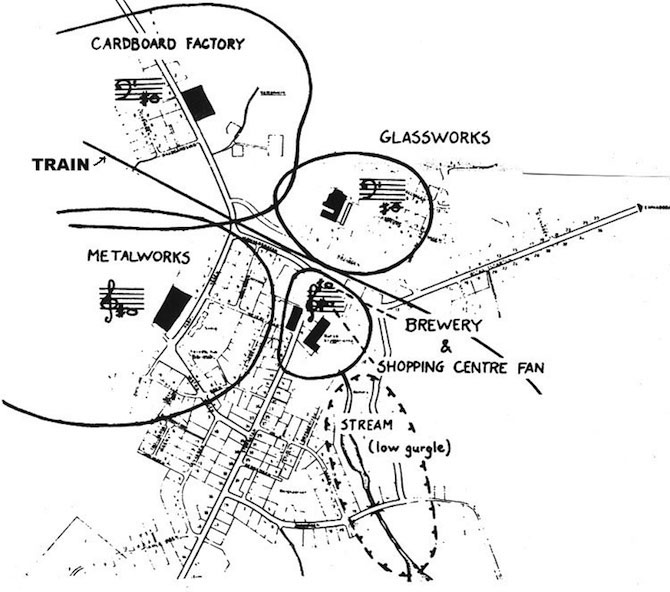

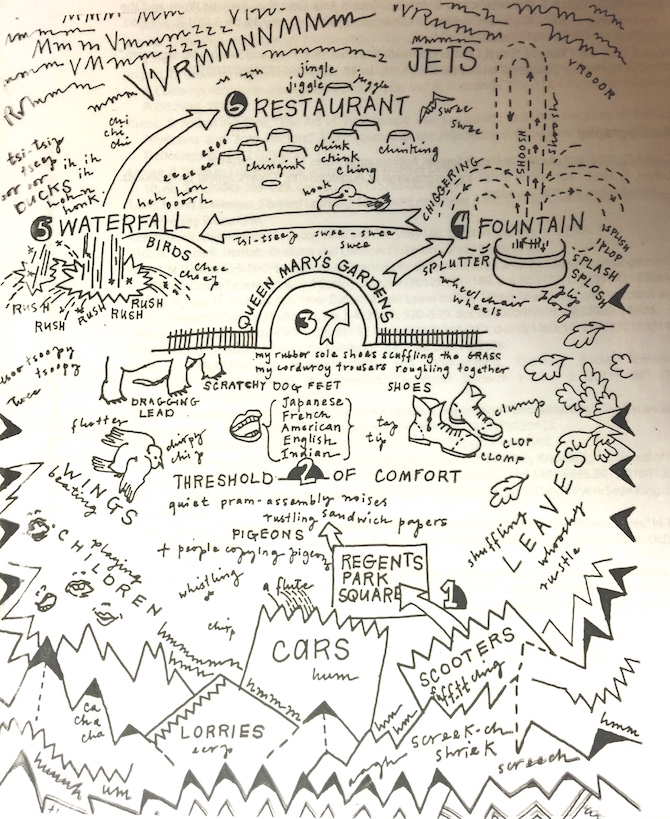

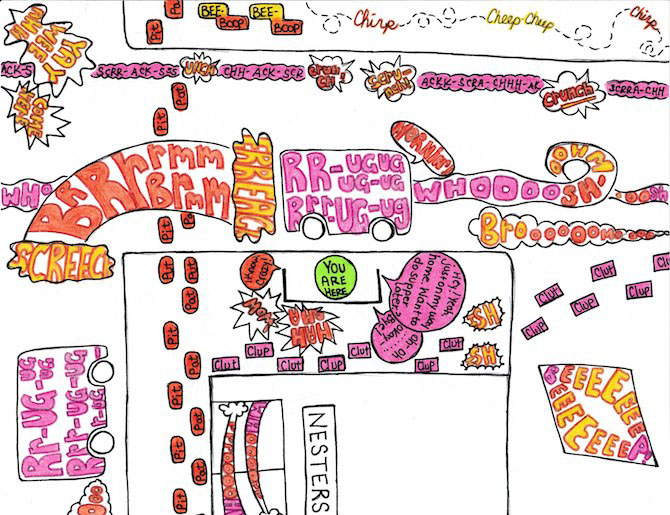

There are a multitude of ways to go about engaging with sound in "real" or non-real time that lend themselves to different forms of sensory attention in the moment. One method that was developed as part of the World Soundscape Project is the use of a "sonic graph," which entails logging sonic events, textures, and ambiences through an often ad-hoc notation system similar to graphic musical notation.

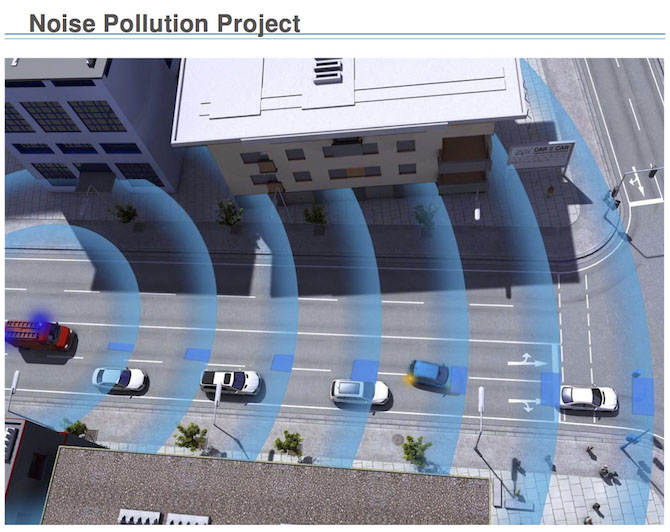

Sonic graphs are created from a stationary position either at intervals of time or for a particular duration, such as the one from the Vancouver Soundscape Project (Davis, 1975) that represents the rhythms of non-human life in a local natural habitat. A sound map, on the other hand, is a spatial "bird's-eye view" of a given area with the intention of capturing something more general about the soundscape, including the prominence of different sounds and where they originate in the soundscape (acoustic profiles); the timbral and textural qualities of different sound sources (often represented through evocative customized graphic notation); the ratio of different categories of sounds (using a "soundcount" sheet); and the relationships of different sounds relative to the listening subject. Soundscape monitoring projects can be themed—for example, around issues of noise pollution, a specific urban neighborhood, or a unique community event.

Time and time again, students gain a realization through the soundscape monitoring exercise that environments are a lot busier than we realize and the relationships between the amplitude (loudness), timbral qualities (spectrum), and the spatial position of sounds are more complex than we assume. Quite simply, students discover a lot more sounds than they expected and their perception works in stages—it takes time for their ears to fully grasp a soundscape, as well as to develop a toolbox for representing sonic events, acoustic profiles, and discrete sonic properties. Time spent listening intently produces not only reflections but also an emerging relationship to the soundscape—a kind of aural literacy of the sounded environment.