Sounding the Stories of Isla Vista Archives, Microhistory, and Multimedia Storytelling

Introduction

Three young men rise before dawn to catch the best swell we've seen on the Pacific Ocean in weeks. A woman wearing a thick sweater and short shorts is just getting home after studying in the library all night. On the streets, littered in every curb, you'll find beer cans and broken glass bottles that once held the cheapest liquor money can buy. As the sun comes up over the ocean, students wait in an outrageously long line at the popular local café, Bagel Café, for a crucial shot of caffeine before their 8 o'clock classes. Everyone is on a bike or skateboard, even the police officers—the sounds of wheels on concrete is everywhere. On the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) campus, the student-run bike repair shop comes to life with the sounds of worn-out bike tires being replaced and bike chains getting adjusted and oiled.

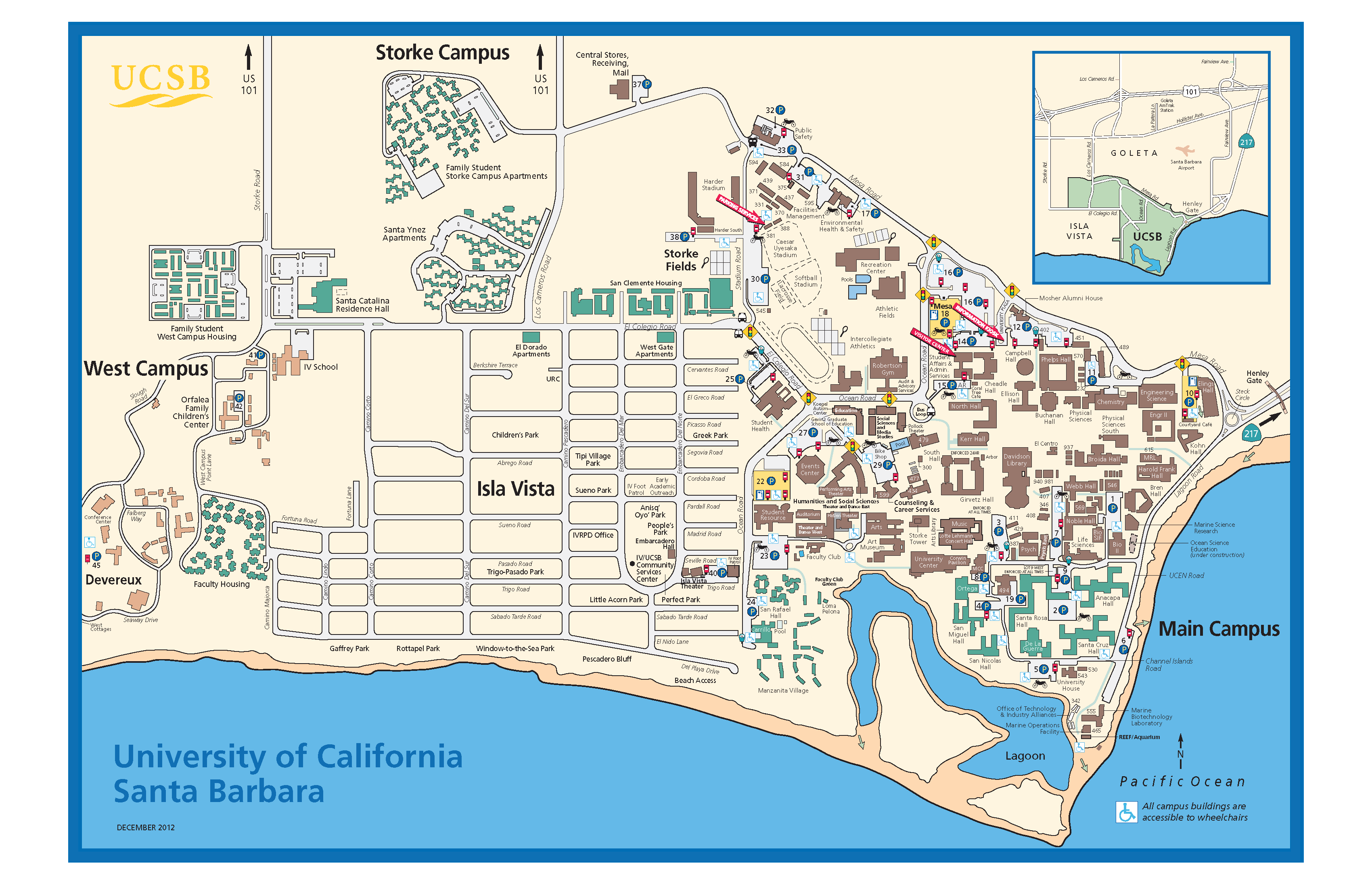

These are a few glimpses into the stories of life in Isla Vista, California—better known as "IV"—the town neighbouring UCSB. This is a place with two identities: For some, it is a beach-side paradise for college students; for others, it is an overcrowded neighborhood often associated with destructive partying, violence, and substance abuse. In sum, Isla Vista is a place upon which labels are regularly applied. For example, this town isn't even really a town—it is officially designated by Santa Barbara County as an "unincorporated place." It is also designated as a "census-designated" place by the U.S. Census Bureau because of its concentrated population: 23,000 people live in this area that is just under 2 square miles.

Yet, despite the sizable population and the potential tax revenue, neither of the adjacent towns (Santa Barbara and Goleta) has wanted to incorporate this haven for college students. And so Isla Vista remains largely outside of the regulations and long-term city planning that you would expect for such a crowded area. UCSB students make Isla Vista their homes for a few short but formative years. And in that time, they develop a strong sense of community. However, most students come and go with relatively limited opportunities to address some of Isla Vista's long-term problems. No one quite knows how to solve a problem like Isla Vista.

In a Multimedia Writing course at UCSB, a course dedicated to composing with new media, we use soundwriting to empower students to discover, create, and share original, complex histories about this community. Towards this goal, we have created the digital Oral History of Isla Vista Archive (OHIVA) as a digital platform for Multimedia Writing students to archive and curate interviews and stories of Isla Vista community members. Students utilize a variety of skills to complete their work with the Oral History Archive: They learn about and employ oral history and archival research methods, they record and edit audio about Isla Vista, and they strategize multimedia writing in a lot of forms. As a result of these projects, we have found that students are able to use soundwriting to engage with the complex, often contradictory, work of telling the hidden stories of Isla Vista in ways that writing alone cannot capture. And in the end, they not only learn more about Isla Vista, they also learn how composition can be an opportunity for deeper engagement with the spaces and people in their communities.

In our chapter, we will begin by outlining our initial pedagogical goals for creating the archive; specifically, we will relate how soundwriting enables both microhistories (see Levi, 2001; Ginzburg, 1993; McComiskey, 2016) and storytelling (see Cavarero, 2000; Lambert, 2013; Farman, 2015) as a basis for teaching multimedia literacies to undergraduates. Next, we'll describe and evaluate the choices made in designing the assignments, pointing to the affordances and limitations of these choices. Turning next to the student work itself, we will feature samples of student work and our students themselves will narrate their engagement with soundwriting and their processes for creating content. We'll conclude by discussing and reflecting on how this soundwriting represents an intersection of our thinking about microhistory and digital storytelling, and, acknowledging the future-orientation of the assignments, how we see these assignments continuing to be used in future multimedia writing classes. Throughout our webtext, students' voices will serve as counterpoints that narrate and apply many of the ideas that we introduce in our text.

Josh's Pedagogical Goals

Josh's Pedagogical Goals:

- Fuse microhistorical and everyday practices to promote more situationally aware writing

- Apply soundwriting to microhistory to help understand community in more complex ways

- Use soundwriting practices to encourage rhetorical thinking about portraying stories

- Promote civic engagement

In my multimedia classroom, my approach to teaching is grounded in my commitments to seeing composing as a practice inflected by place (Dobrin, 2001; Reynolds, 2004) and as a fundamental act vital for community literacy and engagement (Flower, 2008; Long, 2008). Based on these commitments, I wanted to see how I could employ multimedia through the twin lenses of "microhistory" and "everyday" practices to encourage students to engage with their local community in more intentional and situationally aware ways and to help them participate in creating narratives grounded in a specific place and history.

Like Trish, I want students to use multimedia to create stories—specifically, stories of experiences, such as reflections, teaching stories, and histories. As I designed this assignment, I envisioned Isla Vista as a rich site for the gathering of complex histories, and I believed that the collection, digitization, and circulation of audio oral histories of Isla Vista might represent a potent counterpoint to the almost exclusively negative media portrayal the community receives. In particular, I believed that we could approach this project by using the strategies of microhistory fused with the power of soundwriting to help us understand a complex community in deeper and more focused ways.

Trish: How did the use of audio change or affect the way that you engage with the Isla Vista community? Or, the use of audio but also this particular research project—how might it have changed the way you view or engage with the Isla Vista community?

Arie: Well, it definitely forced us to be more cognizant of everything that was going on because, when you're recording and you're trying to get useful stuff, you have to be, I mean, more alert and more on top of things, but, using audio in a place like Isla Vista, it's… it was really interesting because, for one, the first assignment we had to do—just to practice—was just recording ambient sounds in IV. And just doing that was kind of… it was really strange because we played it back and just the things you hear… they were just so… surprising. We just sat at a corner at Pardall [Road], just recording for like half an hour, and listened to it and then it's just… it really captures everything that's going on, and I'd never realized how much audio can add to anything—and especially, I think, in IV, a community where most people travel around by foot or by bike, you pick up a lot more stuff than you would, say, in downtown Santa Barbara where there’s just cars everywhere.

So adding audio to IV, where a) you have people on their feet, and b) there's, most of the time you have, you can hear music playing from somewhere in any point in time. Having audio really just added to the [liveliness] of our project. And, again, I think it really embodied what IV is and what everyone here is all about.

Microhistory represents a shift in focus in historiography: Whereas general history may tend to the more abstract narratives of history, microhistory focuses on the "particular." This "particular," as István Szijártó (2002) described, is highly specific and individual—placing "lived experience at the centre" (p. 212). By taking a microhistorical approach, I hoped that we could cut through the more abstract (and almost exclusively negative) narratives of Isla Vista and emphasize the lived experiences of a very complex, creative, and wonderful community.

Trish: Can you tell me about the experience editing the audio—so this is kind of a follow-up—the experience editing that audio and incorporating or using it in order to tell your history at that moment in time?

Arie: So, I mean, the audio kind of provided a really cool component to it because, I mean, obviously we could have just gone out and asked a bunch of questions and just written up little articles or summaries of each band—which we did—but having an audio component when you are actually hearing the people speak is much more immersive. So if you put on headphones and you're listening to their music playing and listening to them speak and you're reading alongside, it's just a much more multifaceted experience, I guess.

So, that's what we really… that was the main aspect of using the audio in just that it created that much more of an immersive experience—and especially so with our topic or our people, like the bands. Having audio in it… it really wouldn't have been the same without the audio.

As Sigurður Gylfi Magnússon and István M. Szijártó (2013) emphasized, microhistory is also grounded in the premise that reality is only accessible via language; it is not an attempt to "recreat[e] the reality of past times" but, instead, seeks to acknowledge and examine the "fragments of reality" we do have (p. 150). Similarly, Giovanni Levi (2001) argued that the microhistorian is interested in the "fragmentation, contradictions and plurality of viewpoints which make all systems fluid and open" (pp. 110–111). These fragments are ambiguous and require the interpretation of the microhistorican researcher to make conclusions about it. I saw the use of sound as a powerful way to collect these fragmented viewpoints from the Isla Vista community; I also knew that, by asking students to edit these audio interviews for the purpose of their digital exhibits, they would have to reflect on and strategize how they would interpret and present these particular slices of IV's reality.

Trish: How do you use the audio to change or affect the way that you engage with the Isla Vista community that you focused on?

Shay: I talked to them more personally and directly, I think, than I would of—the specific people I interviewed. But you kind of just view—someone did, one group did, I think, all bands, which, me working at a radio station thought was great, and I instantly was like, "We should air this on our station!" and stuff. So, it puts it in a—it almost puts you in a power position because you get to decide what's important enough to document and who's important enough and who's story do you want to know? Everyone has a great, interesting story, but you start thinking of people as, like, maybe more of what they're involved in, like you think of them as the organizations they're involved in and what do you want to highlight… or groups that they're categorized as—like the houseless community isn't really like a group like an organization is, but you think of people more in that way and like what stories do you want to share. The sound kind of gives you that—that project gives you that power, I guess.

Isla Vista is also a community with a long, often contentious, history of political activism, and I saw microhistorical principles as a productive vehicle for pointing out the issues Isla Vista citizens face while also highlighting figures that were actively engaging with this issues to improve the community. Magnússon and Szijártó (2013) saw microhistory as a means of demonstrating the idea of "normal exception" in which individuals are the principal focus of investigation (p. 35). I find microhistory to be especially compelling because it represents a way to write history that places emphasis on individuals as empowered actors that can have an impact on larger social structures; it's also a field where students can participate actively in their local communities by seeking out and talking with local figures involved in important contemporary events. And so, as a whole, I hoped that by learning about these activities, students might be more willing to be more civically engaged during their time in Isla Vista.

I also envision the Oral History Archive of Isla Vista as grounded in my commitment to everyday communities, both as a part of life worth exploring, and as creative foci for a wide array of composing practices and experiences. In fact, as Levi (2001) himself pointed out, there are certainly connections between histories of everyday life and microhistory. Specifically, both reflect a commitment to "go beyond impersonal social structures and processes to the concrete life experiences of human beings" (p. 114). I wanted my students to use soundwriting to engage with communities and present and circulate their stories and experiences through digital means, and I hoped that this would ignite conversations and questions about how multimedia plays a role in community formation. In addition, I wanted students to use multimedia reflectively as a means to reflect both collectively and individually about how we use multimedia and how we can use it more effectively, ethically, and equitably.

Trish's Pedagogical Goals

Trish's Pedagogical Goals:

- Fuse storytelling and writing with sound to shake us out of compositional ruts

- Compose with community voices to build empathy and relationships

- Use soundwriting practices as a mode of attending to the embodied experience of composing

- Promote civic engagement

In my multimedia classroom, students learn to compose multisensorial experiences that engage our entire bodies. A major challenge to this task is that we all—both students and professors—are often stuck in what Kenneth Burke (1984) called "ruts," an entrenched sense of what is the correct way to act (pp. 78–79). These are "ruts which experience itself has worn" (p. 79); they are entrenched practices—including practices of writing—that we learn and cultivate throughout our educations. When students enter a multimedia writing classroom, they continue to draw upon their prior knowledge of text-driven, academic writing contexts. The experience of traditional academic writing, as our students frequently tell us, is excessively cerebral, unaffected, impersonal, and detached. To counter these experiences, I use soundwriting and storytelling to help students move towards writing that creates more personal, holistic, embodied experiences.

My understanding of soundwriting and storytelling are both informed by the feminist philosophy of Adriana Cavarero. For Cavarero (2005), the power of voice exceeds the meaning of words. In addition to words, "the act of speaking is relational: what it communicates, first and foremost, beyond the specific content that the words communicate, is the acoustic, empirical, material relationality of singular voices" (p. 13). Voices have political and personal power because they speak not just words but also the uniqueness of the embodied speaker and relation between that speaker and her contexts or conversant. This is especially important for our students: They are the majority in Isla Vista, so the minority populations often go unseen and unheard. Students use the assignment as an opportunity to connect with members of their community that they may otherwise never meet.

Betsy: Because when you hear a human's voice, you're just like… oh that's… you connect with it more? It sounds more real instead of just reading an article [where] you just skim through it and you're like: "Whatever. We're done." With sound you have to take the time to listen to everything and just hear that person's voice and you could just… the tones, too, also play a part in telling a story. And, for the police, we have a certain perception about them, but if you hear their voice then, they're just laughing and just like… you can hear that genuine… within what they are saying and how passionate they are, which you wouldn't… if you read a quote online or on paper, you can't hear the same thing, or like feel or hear the same thing.

Sam: When I think back to that assignment, and when I was going around collecting audio and visual and just newspapers, going around from just place to place, it was almost like a holistic, like, fun day to go around and get really connected in the community. In the same sort of sense you can read statistics and brush past them because they're statistics and you see them all the time—if you go out and you talk to people, which I had to do, if you go out and interview people and take photos, it's not like a social contract, but you're making a connection that really made me feel more part and more proud to be a part of a community. There's a lot of things—I live on DP [Del Playa Drive, a major street in IV, infamous for student parties], so there's a lot of things that I have to complain about—when it comes to noise, garbage, obnoxious neighbors—I'm using "obnoxious" as a euphemism—but a lot of that sort of would melt away a little bit as I would collect information or hear how people felt about the community and how attached they felt. So, it definitely was personally really healthy for me.

Building on these philosophical commitments, soundwriting requires that we use our entire bodies when composing and that we compose for a fully embodied experience for our audiences. As Steph Ceraso (2014) asserted, soundwriting, when used to its potential, should defamiliarize or surprise. And part of this surprise of writing with others' voices is that students feel both the uniqueness of the human speaking as well as a tight sense of connection with the speaker. When listening to someone’s voice, we learn not just their ideas but also we learn of their embodied particularity though the breath, tenor, warmth, and affect that come through in voices.

Sam: I wasn't the one writing the text, so when I actually got the text, I read through it, and it was like, "OK, this is fine—we're telling somewhat of a story here." But when I put that in together with the audio as they told me which ones matched to which, it did, in fact, bring it to life and made it sound more human and more relevant, to be honest. I think it adds a lot of character and almost warmth to the entire project. I definitely liked putting in audio—it was fun.

I further help students to compose embodied experiences by framing their soundwriting as a form of storytelling. Through stories, we know who we are, where we came from, and how our world came to be built gradually through the work of men, women, words, technologies, serendipity, tragedies, and great successes. From the insides of caves to the feeds of social media, we tell stories to construct and share comprehensible narratives of our lives, our communities, the places we live, and the things we’ve seen. Narrative is also important for Cavarero (2000) since, like the power of voice, narratives also communicate the uniqueness of an individual or community. Cavarero unfolded a theory of "narrative self" in order to demonstrate the political and personal importance of storytelling: Rather than broad histories, narratives focus on who a person is in a specific context. Paralleling Josh's interest in microhistories, my courses apply theories of storytelling to locate and engage with the particular and situated histories of Isla Vista.

Sam: It really makes it feel so much more real because we're flooded with advertisements all the time, just figures, numbers, whatever, and it becomes meaningless until you put audio into it and then it's like: "Oh, these are real people, and this is really happening, and I actually—I can't just not care." It's weird—hearing someone's voice makes it harder to not care.

Josh: Yeah, isn't that interesting—there's some sort of connection that happens.

Betsy: I did not know the history of IV before this. So, this class forced me… or encouraged us…

Josh: That's the word we use… encouraged!

Betsy: … encouraged us to read up about Isla Vista, what we thought was important for other people to know. And just like… because we live in this town, and we usually just connect with other students and faculty on campus, but I think it just made us more aware of our surroundings and… it's not just a student town—it's also all these other people play a part in the community.

By including voices and stories, students begin composing from a different starting place: They start with the uniqueness of individuals in specific contexts. In the composition process, they work to share the unique experiences and voices of individuals and to build a sense of connection with audiences.

In the end, the students may use more or less audio than text. The purpose of this flexibility is not necessarily to tell exclusively oral histories. Rather, the purpose is to use the unique affordances of soundwriting—both voices and stories—in order to get students out of their compositional ruts. With soundwriting, we can compose with the embodied richness of voices in contexts and the embodied experience of listening for the audience. With an embodied experience as our primary goal, students may then make rhetorical choices with any number of modes and media, as long as they compose to create purposeful, compelling embodied experiences.

Assignment Description: Trish and Josh

At UCSB, we only have ten weeks for each quarter. This creates a fast pace, and at the same time this ten weeks allows us to focus on one single project that students plan, draft, revise, and present. For Trish, the single project is a multimedia story that students write for public audiences and may create with a range of different media, including audio, image, text, and video. For Josh, students work collaboratively to gather multimedia artifacts (sounds, images, documents) for the Oral History Archive, and then students curate digital exhibits based on the materials they collect.

The process for designing these projects begins by looking at other examples of texts that demonstrate the intersections among multimedia, archiving, and history, such StoryCorps. We also explore and discuss other examples such as UCSB's Cylinder Audio Archive or The Library of Congress's archive, "Voices from the Days of Slavery." In each case, we talk about how history is presented in these archives—from how the material is organized, to how it is presented, to how multimedia plays a role in our engagement with the archival materials.

In the next stage, we explore the histories of Isla Vista as students immerse themselves in archival research. The UCSB archives are rich resources for oral histories, photographs, and material artifacts collected from the past 75 years. In particular, we focus on the Santa Barbara History Collection, which includes the Community Development and Conservation Collection, the Local History Files, and the Isla Vista Archives. Students are given a tutorial by a Special Research Collections Librarian and are encouraged to explore a variety of different boxes in these archives. After this introduction, students return to Special Collections several times as they gather different artifacts that they digitize for their own exhibits.

After this introduction to the materials in UCSB's Special Collections, we talk about what students discovered, what they found interesting or surprising, and what forms of media they thought had the greatest impact. In particular, students pointed out several things: that many of the issues that were pressing in the 1960s and 1970s remain with us today; that a strong tradition of student-driven advocacy (which involves a wide array of composing practices) continues to this day; that, ultimately, while Isla Vista has remained a site of many contestations, it has always been a site of vigorous creative activity by all residents, including students. From these archives, students learn to see their own lives as intimately linked to, and not that different from, the many generations of students who lived in Isla Vista before them.

In Trish's course, the students then collaboratively create multimedia stories. They must go out into their communities to collect images, artifacts, audio, interviews, and video. Then, after they assess the range of materials they've collected, students decide what content will best bring the story to life and what modes best appeal to their audiences. This means that some groups choose not to use soundwriting as a key element of their projects. Instead, as a class, we discuss the relative affordances and constraints of the different modes of storytelling. Then, the student groups decide what mode best fits their rhetorical needs.

Sam: It really… so the Oral History project was super vague—which is nice. It gives people a lot of freedom to experiment and, with that freedom, you saw a lot of different, really good articles. People… so the really salient one is the geography one that talked about how the bluffs were falling, but like some of the more, I want to say… what's the term "heartjerking" or "tearjerking"?

Josh: Tearjerkers?

Sam: … the tearjerkers were the people who talked to the homeless people. So, I really like this assignment as a whole because it let people go and explore their community because we're constantly in classes and maybe, like me, we get involved with stuff that doesn't let us connect with our community as much. So, I really liked it for that.

Finally, they compose their story drafts and have two weeks for review, revision, and rethinking their stories with feedback from the class. In the end, the students share their projects with their communities. The class hosts a showcase in which we invite the story participants as well as interested community members. In addition, several of these projects have been selected for publication on UCSB's Interdisciplinary Humanities Center community portal.

In Josh's course, students collaboratively create digital exhibits in the Oral History Archive. Students select a specific group to focus on in Isla Vista and arrange and record interviews with members of these groups; these interviews become the core part of each group's exhibit. In addition, students write text to frame these interviews in their digital exhibit, describing the context of these groups in Isla Vista and incorporating media they have gathered from Special Collections into their exhibit. When they complete their exhibits, students then present them to the class, describing their choices in designing their exhibit and any challenges they encountered along the way, while allowing other students to navigate their exhibit and provide additional feedback.

See Trish's full assignment description (PDF).

See Josh's full assignment description and the permission form he used (PDF).

Student Projects

Three student projects from our classes are particularly interesting examples of the work that went into the Oral History of Isla Vista Archive: "Housing the Houseless: Pescadero Lofts" and "The Music of Isla Vista" from Josh's class, and "Isla Vista Law Enforcement" from Trish's class.

"Housing the Houseless: Pescadero Lofts"

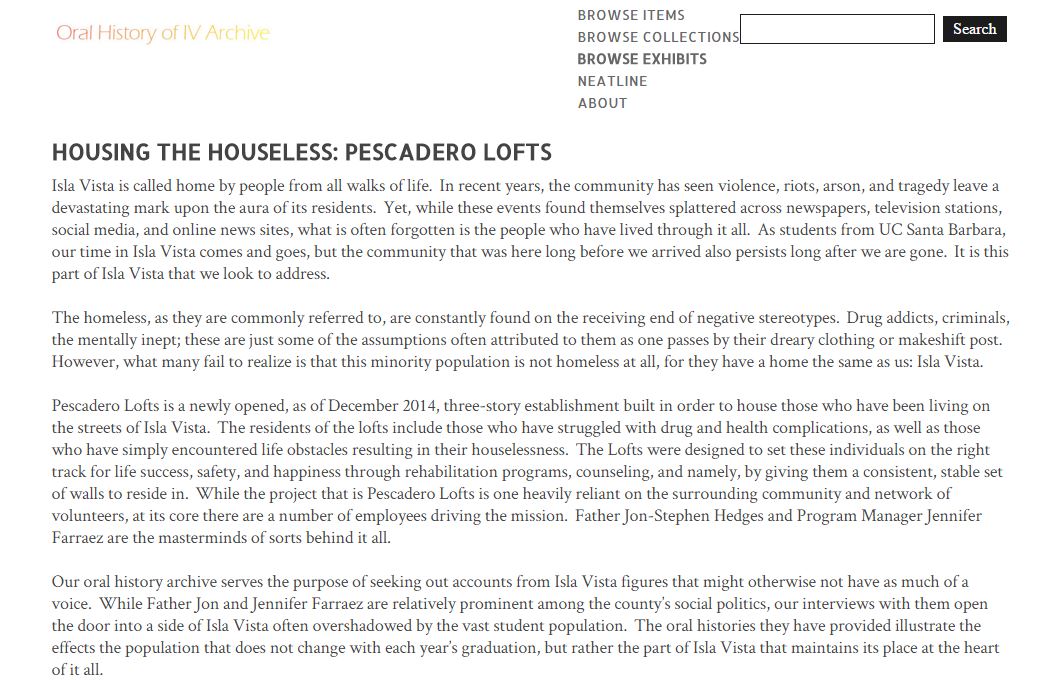

The first exhibit, titled "Housing the Houseless: Pescadero Lofts," focused on the houseless in Isla Vista and, in particular, the Pescadero Lofts, a three-story rental housing project recently built to house those who have been living on the streets of Isla Vista.

These students pointed out that they had very specific purposes in creating their exhibit: "to [seek] out accounts from Isla Vista figures that might otherwise not have as much of a voice" and to challenge misconceptions of the houseless who are "constantly found on the receiving end of negative stereotypes."

Trish: What were some of your goals of what you wanted to kind of… like, you did the project that you care about, so what were some of your goals for the end product?

Shay: I guess super-initially was to break any stereotypes that most people, honestly, have about that population—partly because one of the first things that was said was that was a group to not choose, and that's kind of my style. I don't know, I usually do the assignment differently, and so I asked Josh and I explained to him that I do work in it, so it's not going to be just a stranger going up and getting whatever reaction happens. And… so I wanted to break any stereotypes, and then I wanted to kind of share their stories through… we didn't have time to interview as many people as I'd like, but through people who are in the service of those people, so who serve the under-served basically, 'cause both of them are not actually houseless people but they've spent forever working in that…and working specifically in that in Isla Vista and Santa Barbara. So they're hyper-knowledgeable about that.

HOUSING THE HOUSELESS: PESCADERO LOFTS

Isla Vista is called home by people from all walks of life. In recent years, the community has seen violence, riots, arson, and tragedy leave a devastating mark upon the aura of its residents. Yet, while these events found themselves splattered across newspapers, television stations, social media, and online news sites, what is often forgotten is the people who have lived through it all. As students from UC Santa Barbara, our time in Isla Vista comes and goes, but the community that was here long before we arrived also persists long after we are gone. It is this part of Isla Vista that we look to address.

The homeless, as they are commonly referred to, are constantly found on the receiving end of negative stereotypes. Drug addicts, criminals, the mentally inept; these are just some of the assumptions often attributed to them as one passes by their dreary clothing or makeshift post. However, what many fail to realize is that this minority population is not homeless at all, for they have a home the same as us: Isla Vista.

Pescadero Lofts is a newly opened, as of December 2014, three-story establishment built in order to house those who have been living on the streets of Isla Vista. The residents of the lofts include those who have struggled with drug and health complications, as well as those who have simply encountered life obstacles resulting in their houselessness. The Lofts were designed to set these individuals on the right track for life success, safety, and happiness through rehabilitation programs, counseling, and namely, by giving them a consistent, stable set of walls to reside in. While the project that is Pescadero Lofts is one heavily reliant on the surrounding community and network of volunteers, at its core there are a number of employees driving the mission. Father Jon-Stephen Hedges and Program Manager Jennifer Farraez are the masterminds of sorts behind it all.

Our oral history archive serves the purpose of seeking out accounts from Isla Vista figures that might otherwise not have as much of a voice. While Father Jon and Jennifer Farraez are relatively prominent among the county's social politics, our interviews with them open the door into a side of Isla Vista often overshadowed by the vast student population. The oral histories they have provided illustrate the effects the population that does not change with each year's graduation, but rather the part of Isla Vista that maintains its place at the heart of it all.

As they write in their introduction, "The Lofts were designed to set these individuals on the right track for life success, safety, and happiness through rehabilitation programs, counseling, and namely, by giving them a consistent, stable set of walls to reside in." Students met with and interviewed two key figures that played critical roles in both the support of the houseless in Isla Vista and in the creation of the Lofts themselves, Father Jon-Stephen Hedges and Program Manager Jennifer Farraez.

Shay: Well, first we were deciding what group to do and bounced around some ideas, but pretty quickly we were satisfied with this one. And then it was scheduling people in the same place which is always, I think, the hardest task of any project ever. And we didn't actually manage to get anyone else to be able to meet me to interview them, which was unfortunate. But everyone else kind of helped with the back-end of things like transcribing and all the editing after and getting it onto the website. And then it was just set up a meeting with the two people I wanted to interview. And I interviewed them, actually, on the same day 'cause Father Jon works in the Lofts and Jennifer lives there, so it wasn't too difficult to get them at the same time, at the same place, for once. And they were pretty open to the idea; Father Jon's been… if you look him up, he's on YouTube, they've been interviewed for things, they're not too shy about doing that. So, we interviewed them, and I got all the files on—I used Audacity on my laptop—and then I brought it back to my group. And we spread them out, broke them up into… they had to be a certain size, which was one of the, probably, the larger limitations of this project is having the file size have to be so small—I think it was 50 megabytes or something? So, the interview would be broken up into almost just questions—it wasn't even a certain amount of… I mean it wouldn't make sense to do time—it was just one question. So we broke them up and then spread the pieces between the group members and transcribed it and put it up, and then someone did metadata for them. That was pretty much the gist of that.

Note: This transcription is unaltered in order to leave the original student work intact.

JENNIFER FARRAEZ: PART 1.1

Q: What first brought you to the Pescadero Lofts?

A: So, I feel like I need to answer the backstory on why the Pescadero Lofts is even in Isla Vista. It was created by the county housing authority to specifically house the chronic homeless of Isla Vista about four years ago. A representative from housing came to Father John at our Monday night dinner and asked him what he thought about creating a place for the chronic homeless of Isla Vista. And he said "it's a wonderful idea", pulled me into the next meeting and we all sat down and sort of brainstorming what this could look like, because you can't just plot down people that abandoned on street forever and housing and expect them to succeed, you need supportive services along with that housing so the people have the support thing they need to be able to figure out how to live within once again, on a practical level, on an emotional level, in everyway possible. It's a major, it requires a major cultural change to move back inside after you've been out there so long in survival mode, when all you energy out on the street goes into food, clothing, shelter, safety, to come back in within walls, and be alone with your own thoughts, and all your memories of the things you lost before you ended up on the streets. And that could be very scary for people, so without supportive services, people will often return to the streets. So, we knew, Father John and I knew that people would need a help support, would need recovery support for those who use drugs and alcohol, would need help with basic living things, like learning how to budget, learning how to cook inside again, maybe they've never learn that, learning how to get along with others in a community that they didn't chose for themselves but they are randomly placed here together with neighbors they didn't chose perhaps.

In particular, the experience of interviewing the key figures for this exhibit had a great impact on Shay, one the group members who was especially committed to the project.

Shay: I actually interviewed Jennifer in her home, so that was an ordeal, like different. And it was very… she was very welcoming and it was very laid-back 'cause it was just in her home on her couch. In the structure that was literally built to [alleviate] the problem that they were talking to me about. So it was very like… this is kind of surreal. It's just simple, it's in someone's house, but it actually… it's not just a house to any of the people living there. It is to me, but not to them. And just thinking about those little things and… you could hear like… she told me about—she's a social worker—so she told me about her journey to getting there, so you can kind of hear all these things in her voice, like the different painful events that they’ve gone through. Like Father Jon has… he talks about, he has a wall in his office that's all just people who have died on the street——and so, you can hear, sort of, the sadness in his voice over that or different things, and I find that pretty interesting. And I don't know that you’d focus on it if it was just a video.

Finally, Shay's experiences with sound inside and outside of the classroom are really an important part of her life. As she describes here, Shay devotes a lot of her time to both traditional writing and soundwriting simultaneously. So, the opportunity to soundwrite in class was a pleasant surprise.

Trish: And so, but you work at the radio station [UCSB's on-campus radio station KCSB FM], so could you tell me about your impression going into this project given your experience and your interests?

Shay: So, I think with that it's like, I initially already highly value sound. I think music is awesome and I think… I'm the promoter there, so I love live music, to be specific. I think that's something people should regularly be involved in, either making or doing or listening or writing about… So I already highly valued sound, and I already value the whole thing I'm saying, just paying to just noise because noise alone can tell a whole story and set an entire mood and tone just by itself without pictures or words or like a person in front of you even. You don't have to have the band in front of you to create the mood or anything—although that's great—that's my favorite thing to do. So I think I was like, "Oh, I get to do something that's not writing? That's cool but it's—at the same time—completely related." Which I see as well because the shows that I also have on the air are public affairs, so I write a script anyway. I do both for it—a lot of what I do is sound and writing. And I guess most people kind of didn't before this—this was maybe their first exposure to it.

Trish: Can you talk to me a little bit about that—what do you think is that relationship between sound and writing?

Shay: Ummm… writing…

Trish: That's like a super-hard question, but like: go!

Shay: Writing tends to precede a lot of sound, maybe? Like you'll write a speech before you give it, I write… usually write my shows before I have them or… like, I had a science show and that one was much more prepared; and then I had a music news show and that one—was still prepared though I'd write points I wanted to make, though maybe not as explicitly. Because in the science show, I wanted to be very clear, and the point of that was education and the music one was more about culture. So, I guess writing tends to precede a lot of sound—and then even musicians, not all of them—they used to write music before they performed it. So it precedes a lot of sounds—that's the first thing I thought of when you asked that.

I think that they can play off each other very well, though, because, like one thing… I like radio… so NPR is great because it is very multimedia. They have a transcript—but it's not exact and they have… they always have the audio file and always have a photo or artwork. So it's very multimedia, and it really enhances their storytelling ability. I feel like that is what sets them apart from other things, is that they are good at telling a story and you secretly learn a thing. And I think that's what I always set out to do on air too—I like secretly teaching people things. So, they can't really do one without the other—they can’t not have the written thing and they can't not have the audio or even the artwork or whatever; I think they all work very well together. But having anything separate has you focus on it alone. So I think that what was interesting about our specific project, too.

"The Music of Isla Vista"

Taking a less serious approach, another student group created an exhibit titled "The Music of Isla Vista." This group explored the vibrant music scene in Isla Vista and focused on three bands actively playing at venues in Isla Vista. These bands were entirely comprised of students from UCSB and neighboring Santa Barbara Community College, and all resided in Isla Vista. In particular, this group aimed to focus on the bands' experiences performing in Isla Vista "with crazy tales ranging from stolen mics in the middle of shows to crazy landlords shutting down practices."

THE MUSIC OF ISLA VISA

Fun. Loud. Happy. Ask anyone to describe Isla Vista and it is nearly guaranteed that you will hear all three of those words. A major aspect of the fun, loud beach community is music, a resource that is plentiful. Music is an integral part of Isla Vista, and this exhibit takes a closer look at three of the local bands that are contributing to the vibrant Isla Vista music scene. The bands are almost entirely composed of UCSB and the neighboring city college, SBCC, students, and many of them have ardent followers. Most of their incredible stories are akin to Animal House-esque antics, with crazy tales ranging from stolen mics in the middle of shows to crazy landlords shutting down practices. The musical scene in Isla Vista is entirely its own, but with this exhibit we hope to share some of its unique charm and transport you to a typical day in the life of an Isla Vista band.

This group met with the members of The Oles, The Sun Daes, and OMG, a band of international students, and asked each band about how they formed, what their experiences were like performing in Isla Vista, and how their experiences in California and Isla Vista have inspired their music.

Trish: What were the steps or what was your main process for completing it?

Arie: So, well, first we had to settle on what group we were going to do, and once we had locked it down to local bands, we had to find which local bands were actually still in Santa Barbara—because it turned out a lot had graduated that past June, and since it was a summer quarter, we had to figure that out and once we figured out which bands were still around… well, before that we figured out what questions we wanted to ask them. We came up with a list of twenty questions that we would ask the band members and… then once we'd settled on our list of questions—we kept the same questions for each band—and then we reached out to each band through Facebook, and once we got replies, we set up meetings with them. And a couple were at their practices so we had to go and it was pretty cool. We got to listen in on their practices and then usually just talk to them and have a conversation while they were practicing, so that was really cool. But the transcription afterwards was just… horrible. There was music and just transcription in general was not fun. And then, after that, yeah, we recorded just… we either recorded or had them send us a file of their songs, or like one of their songs that we then spliced in with our interview with them, and then we put it all up on the website with the transcriptions and kind of just tried to create a cohesive portrait of the current scene circa summer 2015.

Trish: Can you just tell me about the project? What did you do?

Jake: So first he gave us the project, and, from there, we had to think of kind of a theme to go for, so our theme was "Music of IV" so it kind of had to capture some part of an IV custom or an IV experience, kind of. So what we did was we had to get an interview with a few bands—I knew a band named Sun Daes and then a couple other of my teammates knew bands.

I think I'm personally interested in music a lot, and so I think that kind of had to do with it and also, because my roommate was in a band, I thought that music's such a big part of IV—and we go… they have concerts on the weekend, they do stuff in the Hub [an event space on campus], they have IV band battles and stuff like that—so I thought that it was such a big part of the culture in IV that I wanted to capture that.

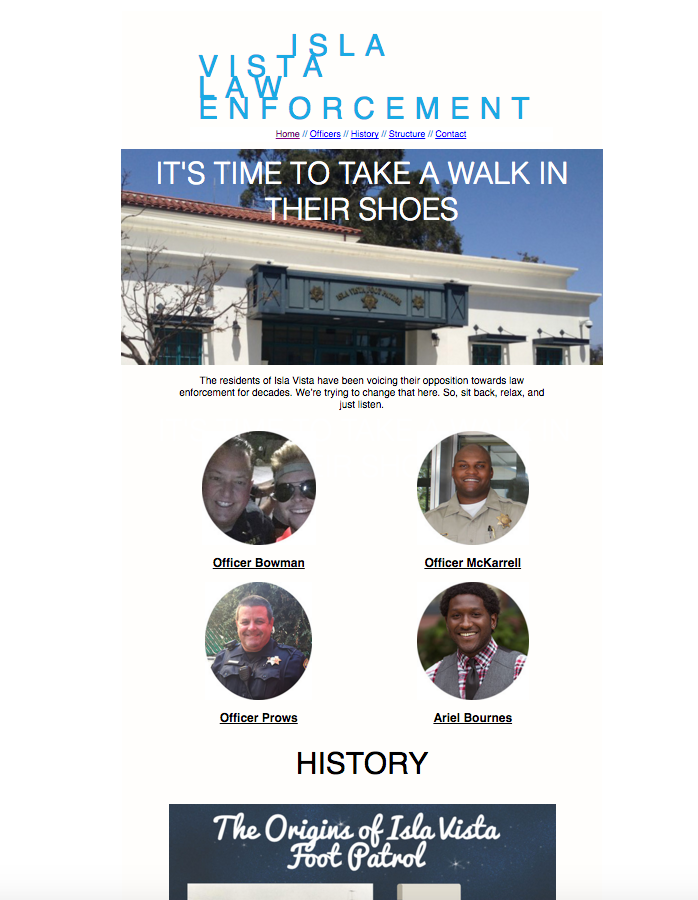

"Isla Vista Law Enforcement"

For Trish's class, the work of Betsy and her two group members highlights the effective use of audio. Their project, titled "Isla Vista Law Enforcement" researched the history of police in Isla Vista and the current policies regarding training and placement of police in Isla Vista. Most importantly, the students used audio from interviews in order to feature four members of the Isla Vista foot patrol, the community policing unit that works most closely with UCSB students.

Betsy: We thought we were going to do purely just clippings from the web, and content from the web, but then we went to office hours with Professor Fancher and she said it would be pretty cool if you interviewed the cops. So our project was about what the cops thought about Isla Vista and hearing their voices instead of just students. Because we see a lot on social media where students just complain or say bad things about the cop. So, we wanted to hear their side and then. So we thought interviewing them would give them more… hearing someone's voice you give them more of their character… more personal… it's more personal. And then our website was basically focused on audio, so we had different pictures of the police and then people could just click on them and see what they have to hear for each of the questions. It was a good experience—we all basically learned how to use all the software last quarter, so it took a lot of time to figure out Adobe Premiere and Adobe Muse. But in the end it all turned out ok—it was a functional website.

Isla Vista Law Enforcement. It's time to take a walk in their shoes. The residents of Isla Vista have been voicing their opposition towards law enforcement for decades. We're trying to change that here. So, sit back, relax, and just listen.

In her reflection on the project, Betsy explains more about what she got out of the project:

Betsy: Before this project, I did not know anything about the law enforcement in Isla Vista. Also, I rarely interacted with any of them in the past three years that I've been here. By conducting interviews with the police and researching how they are integrated in Isla Vista, I was able to learn a lot about their view and how they operate in an unincorporated area. Through this project, I learned to integrated research, creative writing, and different mediums to share a story.

And regarding the group's use of audio, Betsy reflected upon the importance of sound. Sound shows the unique voice that speaks the humanity, sincerity and character of these police officers:

Betsy: My group wanted audio to be the main focus for our multimedia project. We wanted to give a voice to the Isla Vista police officers because we always hear the voices of the residents who complain or praise the law enforcement. With this, we are able to hear the officer's own unique voice. It reminds our audience that the police are humans too. We can hear the sincerity and get an impression of their character in their voice. This is something we cannot fully understand or sense by reading words. These are the affordances audio can provide to multimedia storytelling.

Isla Vista Law Enforcement.

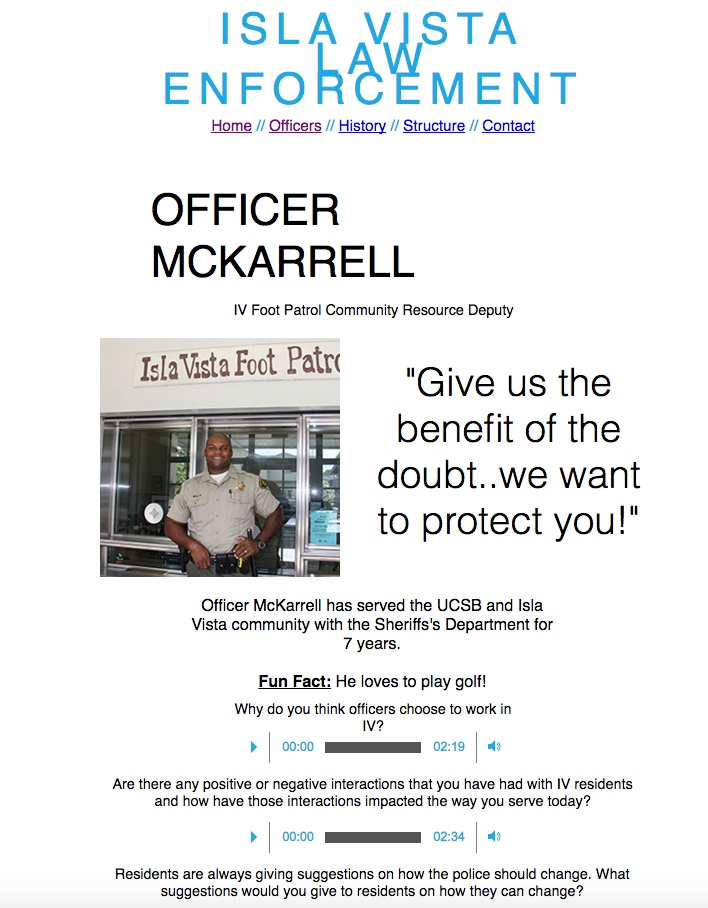

Officer McKarrell, IV foot patrol community resource deputy.

"Give us the benefit of the doubt… we want to protect you!"

Officer McKarrell has served the UCSB and IV community with the Sheriff's department for 7 years.

Fun Fact: He loves to play golf!

Why do you think officers choose to work in IV? [image of embeded audio file]

Are there any positive or negative interactions that you have had with IV residents and how have those interactions impacted the way you serve today? [image of embeded audio file]

Residents are always giving suggestions on how the police should change. What suggestions would you give to residents on how they can change?

You can hear what she is writing about in Betsy's edited clips of Officer McKarrell's interview below. First, one that focuses on what McKarrell finds unique or special about Isla Vista:

Betsy: What makes officers choose to work in IV? What makes IV unique?

McKarrell: Well, it's super, super diverse. There's a lot going on here. And a lot of our deputies, some of them are younger so they can kind of communicate with people their age. Working out in the community outside of IV, it's a totally different beast. It's completely different.

It's a very unique place here. And I think it's fun for a lot of them, quite honestly. They get exposed to so many different things. It's fast paced. IV has its own frequency on the weekends, pretty much. We get such a high volume of calls here that, uh, we can't have it tied into other parts of the county. So on any given day, you can do any different thing here. And I think for our up-and-coming deputies, it's something that they should all do. Because you are exposed to a lot.

You get to see a lot of different perspectives, like, again, it's so unique working with the minds of the university/students of the university than what we normally deal with, which is just community members. Jumbling all of those things into one pot: You're going to be better for it. You're definitely not going to be bored. I don't ever remember being bored out here. And I think that’s part of the excitement and why they want to come out here.

Because, we're a county agency and in some parts of the county you're kind of stuck with what you get. Over here, you might have a lot of money; you might not have a lot of money. You might get one race or nationality. But here, you get everything under the sun. One day I may be sitting here talking to you as an officer and the next I may be giving a presentation and next I may be chasing a bad guy through the streets doing lord knows what. Or a streaker, or you know. So, I think they volunteer to come to this substation because it's fun, it's a lot of activity, and they'll grow.

And another in which McKarrell expresses his care and concern for UCSB students:

McKarrell: I've had pretty… nothing but positive dealings with the community at this point. I've had an opportunity to meet with the actual residents and business owners and different people of IV and speak about their concerns.

I know that the community is ready for a change. That was apparent from Deltopia and Halloween [major parties within IV]. I know that they're ready to jump on the bandwagon, so to speak, and support law enforcement and our efforts. However, there are concerns about some things that law enforcement does. So, knowing that, we've been able to work out meeting times where we can discuss some of the community issues, whether that pertains to the Latino community, Black community, or any other community, any portion of the community here in IV. We've been able to sit down and talk about these things. I can't say anything negative at this point. I have a newly appointed position at my job, where I hear people's concerns and relay that to see how me and the upper brass can figure out some of these problems, these community issues.

I wasn't here for the shootings. I worked in Carpinteria. I was here the night of the shootings and I had to stay behind in Carpinteria to take care of that place. But there was a change. There was this overwhelming presence of support. And it seems recently that that just dropped off the face of the earth.

So I don't know, I think that media has played a big role in changing the way people are perceiving cops and the work that we do nowadays. But again, I can speak for Sheriff's department and all of UCPD and all law enforcement, and at the end of the day, we're just trying to protect people. Even if we have to protect them from themselves, that's what we're going to do. And, sometimes, people can perceive that as us being the big brother or daddy telling people they can't have fun. But I assure you that, if there's a law or a rule, there's a reason for it.

So I say to the community members that may not understand what we do, at least give us the benefit of the doubt and the confidence to know that we're out here trying to do the best we can by them. But, as far as negative interactions at this point, I haven't had too many.

Reflection

As we reflect on these projects, most significantly, we feel that the quality of our students' work as well as the level of their thinking demonstrated in their reflections and interviews suggest that soundwriting has been successful in our classes. First, we see that soundwriting is a mode of guiding students to engage with their communities; we also have found that students more actively assume a form of agency by virtue of their abilities to record and share the complex narratives of their home, Isla Vista.

In every interview, students agree that the best part of their experiences with these projects all had to do with audio: Students loved interviewing people in the community and learning more about these people by talking to them face-to-face. In particular, students across the board pointed to the power of sound as a part of a powerful learning experience. Students participated in digital making that traversed the digital and required encounters with the material and the embodied. Specifically, students not only had to negotiate unfamiliar digital platforms (Omeka and Adobe Muse) that were both demanding and limiting at times, but they also had to perform digital work that required meeting with individuals in person and on-site. Students frequently reported back on the challenges of recording on-site interviews and the limitations of the digital platforms. And so, we see that the making of these digital exhibits and stories required students to think not only about how their recorded interviews may translate (or not) into the digital realm, but also about how using digital tools in different places inflects that translation.

We also find that these projects have been successful in countering negative and unrealistic narratives circulating around Isla Vista. This seems to have been a goal that students, in particular, were deeply committed to—many students pointed to this in their exhibits, stories, course reflections, and interviews after the assignment was completed. That being said, as "The Music of Isla Vista" exhibit group demonstrated, the "dialogue" between microhistorical narratives that Josh hoped for and the negative narratives of Isla Vista that almost exclusively emphasize the community as a "fun, loud beach community" and place of excessive drinking, partying, and altercations with the local police was much more complex than we had been giving it credit for. While both Trish and Josh were dedicated to helping students see the complexity of stories around this community and how challenging it is to tell a narrative even about a town as small as this, we underestimated how nuanced and complex it really was: not nearly as neatly black-and-white as we thought, even while we understood the complexity of these oral histories.

Upon reflecting further, we do plan to make changes to improve the project. We teach our students the best practices for recording and sharing oral histories, which include recording in a quiet space and using the highest quality equipment available. From our experiences, we have to question how situationally appropriate these practices are for the goals of our students' projects. Regarding the quiet spaces, these projects are histories and stories of a place. The student recordings include the ambiance of the environment and energy in Isla Vista; they recorded at coffee shops and on the streets, capturing the hustle and bustle of Isla Vista life. In Jake and Arie’s project, they interviewed the bands during their practice sessions, which included the noise one would expect from a college band. While this, at times, made it difficult to understand the content of the interview, the recordings gained the rich ambiance of the place in their histories. To supplement the audio, students transcribed the text so that readers could follow along visually as well as sonically.

Regarding the equipment, for most of the students, the highest quality equipment simply means downloading an application on their iPhones. Although we investigated options for higher quality equipment, the ease of access and use made students' smart phones the easiest option. Additionally, students found that the phones were more natural to use and less intimidating for the participants: They could speak more naturally without the presence of a large, intrusive microphone. Hence, for our students, the minimalist technology available was actually the best for this particular rhetorical situation.

In addition, we haven't made enough time in class to critically reflect with students about the broader principles of recording oral histories. As we move forward, we want to allow time to read the instructional texts more intentionally so that students know how to apply these principles. Then we would want to reflect upon their experiences in order to critique or adjust the general best-practices established for oral history. We both see this project as an opportunity for students to resist and adjust instructions in order to convey rich histories and stories particular to Isla Vista.

For us, the most significant limitation of this project is that the students' stories, especially in their conclusions, continue to filter the complex narratives of Isla Vista through a lens that is highly student-centric and also highly privileged. The goal of the project is to urge students to engage with the diverse and complex aspects of their communities. Students do research complex issues like homelessness and community–police relations, and in these stories, tensions and problems are easy to identify. The interviews themselves reveal these many tensions, problems, and unresolved issues. However, in the end, the students frequently compose the stories within an overtly optimistic, sunny, and even simplistic frame. While we ask students to engage with their communities, many times, the students themselves remain at the center of the projects.

Right now, we do not yet feel like we've guided the students to explore the stories that are outside of their particular privileged experience of Isla Vista. Students are going out and building connections in the community. In that way, they are moving towards civic engagement but still resistant to seriously addressing entrenched problems surrounding race, class, gender, and sexuality. Thus, we have also not been totally successful in helping the students to feel comfortable with conclusions that are open and allow tensions to remain ongoing.

In sum, we are currently considering how this assignment might be improved with these subsequent revisions. Whatever form this project takes, however, several things are clear to us: First, using soundwriting as a means to tell historical stories helps build connections between students and communities since it promotes personal, embodied engagement with unique voices; second, soundwriting is a feminist practice since it valorizes the uniqueness of all voices situated in embodied, historical contexts; finally, soundwriting represents a way to change entrenched student practices in a substantive way, asking them to write in ways that are engaging, surprising, and truly exploratory.

References

Burke, Kenneth. (1984). Permanence and change: An anatomy of purpose (3rd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cavarero, Adriana. (2000). Relating narratives: Storytelling and selfhood (Paul A. Kottman, Trans.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Cavarero, Adriana. (2005). For more than one voice: Toward a philosophy of vocal expression (Paul A. Kottman, Trans.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Ceraso, Steph. (2014). (Re)educating the senses: Multimodal listening, bodily learning, and the composition of sonic experiences. College English, 77(2), 102–123.

Dobrin, Sidney I. (2001). Writing takes place. In Christian R. Weisser & Sidney I. Dobrin (Eds.), Ecocomposition: Theoretical and pedagogical approaches (pp. 11–25). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Farman, Jason. (2015). Stories, spaces, and bodies: The production of embodied space through mobile media storytelling. Communication Research and Practice, 1(2), 101–116. http://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2015.1047941

Flower, Linda. (2008). Community literacy and the rhetoric of public engagement. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Ginzburg, Carlo. (1993). Microhistory: Two or three things that I know about it (John Tedeschi & Anne C. Tedeschi, Trans.). Critical Inquiry, 20(1), 10–35. https://doi.org/10.1086/448699

Lambert, Joe. (2013). Digital storytelling: Capturing lives, creating community (4th ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

Levi, Giovanni. (2001). On microhistory. In Peter Burke (Ed.), New perspectives on historical writing (2nd ed., pp. 97–119). University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Long, Elenore. (2008). Community literacy and the rhetoric of local publics. West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press.

Magnússon, Sigurður Gylfi, & Szijártó, István M. (2013). What is microhistory? Theory and practice. London, UK: Routledge.

McComiskey, Bruce. (2016). Microhistories of composition. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Reynolds, Nedra. (2004). Geographies of writing: Inhabiting places and encountering difference. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Szijártó, István. (2002). Four arguments for microhistory. Rethinking History, 6(2), 209–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642520210145644

University of California, Santa Barbara. (2012, December). University of California, Santa Barbara [Map]. UCSB Campus Maps and Resources. Retrieved March 1, 2015, from http://www.aw.id.ucsb.edu/maps/