7. Audible Voice as Synecdochic Identity

Documentary scholar Bill Nichols (2010) maintained that "Documentary commonly makes use of indexical images as evidence or to create the impression of evidence for the proposals or perspectives it offers" (p. 125). Throughout the video footage that we have provided, we must recognize the powerfully indexical and synecdochic quality of video footage. Seeing and sensing Liberty and ourselves on screen seems to invoke not only our situated selves, but our selves themselves! That is, what we seem to access via the footage is not simply a characterization of us, but… us. The indexical quality points to the actual people—the part invokes the whole. However, we want to emphasize, too, the indexical quality of the human voice to be as compelling, if not more so, than the documentary image. In short, it is not the image alone, but the audiovisual evidence that makes video footage so compellingly indexical. In this regard, "having" a voice on video certainly does create the impression of evidence for the proposals or perspectives that the editors of the video offer. But, again, this direct, indexical, synecdochic representation is only misleading if we somehow suspend disbelief in it—if we choose, against our better judgment, to believe that what we see and hear is somehow an unmediated window on what actually happened and that the people we meet are actually the people we meet. They are not. But acknowledging that does nothing to diminish what can be learned by way of the resulting sleight of ear, as what is actually indexed is a fictitious, empathetic, rhetorical person that is invoked by way of the resulting combined voice. That is the power, the responsibility, and the goal of of speaking through the audible voices of others and of allowing others to speak through our own audible voices: empathy.

As we listen to the voices of the two young women in the scene above, we can't help but hear those voices as irrevocably belonging to those two young women. When Liberty narrates from behind the camera, we have no reason to believe that the voice of the narrator belongs to anyone other than Liberty. Her voice is identifiable. We don't need the the suggestion of seeing her mouth move in synchrony with the words to believe that the voice had its origin in Liberty's body. Visual evidence or no, that voice is clearly her voice. And by suggestion we mean just that: Collocations of mouths and voices in film merely suggest origin. As any editor knows, audio and video are edited both separately and together. Consequently, we are able to have computer animated characters (e.g., Gollum in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings series) who have real human voices. Gollum seems to speak, but Gollum does not speak: Actor Andy Serkis speaks for Gollum. Film and video also enable George Clooney to sing so convincingly in O Brother, Where Art Thou? In the film, Clooney lip syncs convincingly to the excellent singing of Dan Tyminski. So, video footage offers no "proof" of sonic origin. Video footage can only ever suggest origin. That said, its suggestions can be powerful; after all, seeing is believing.

But we really don't need to see Liberty speak to believe that she is speaking. Nor do we feel the need to question whether the voice of Jovanna is indeed what we hear associated with her on-screen presence. The scene gives us every reason to believe that it was shot with direct sound: a term associated with film sound that means that the sound that we hear was captured at the same time as the video. Not only do we hear voices in this scene, we also hear the sounds of the camera being held, jostled about, and turned off and on. That suggests that what we hear is not only direct sound, but that the sound was recorded by a microphone attached to the camera. The video footage supports the believability of this suggestion. There is no evidence of anyone apart from Liberty and Jovanna in the room. Liberty even turns the camera to face herself to further suggest that she is not only the narrator but also the camera operator. Consequently, a camera-mounted microphone makes perfect sense. And, speaking as the people who both provided Liberty with the camera equipment and as the people who pulled the video from the tape that Liberty provided to us and who edited the version provided here, we can further support these suggestions as highly plausible.

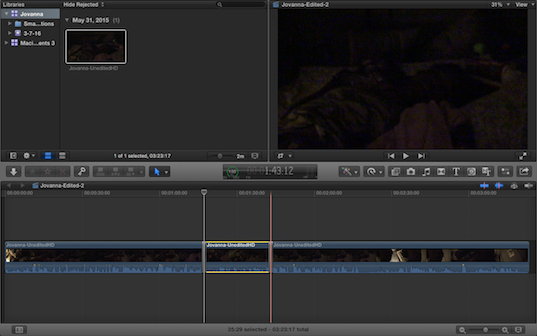

In fact, we made only one edit to this video: As detailed above, we inserted approximately 26 seconds of black screen to occlude the visual action that Liberty narrates (1:17 to 1:43 of the scene—highlighted in yellow in Fig. 3 below). But that insertion is far from inconsequential. As we state above, this visual elimination is arguably one of the loudest vocal appropriations of the entire 35-minute edit. We show up in the middle of the scene that remains otherwise unedited. In this way, we have to recognize that the voice of the editors is characterized not by way of sound as much as by way of choice. In this way, the audiovisual editor seems to retain a substantial purchase on the established discussions of voice that we have characterized above. The audiovisual editor speaks with a metaphoric voice characterized by agency, entitlement, empowerment, and authorship. This metaphoric voice does not share the same sort of indexical or synecdochic quality that audible voices enjoy. We may sense the presence of the editor, but we don't invoke the presence of her whole person.

However, the work of the editor, in general, is characterized not so much by identity but by stealth. Whether we are editing our own works or the works of others, whether we are editing words or images, whether we are editing audio or video, whether we are editing to make amendments or deletions, whether we are editing to take chances or to make corrections, "editing" names an act that involves identifying choices and acting upon those choices in some way. And while Lon Bender (2007), in the epigraph to this chapter, described success in sound editing as making it all seem like it happened, it is clear that someone has done something. Someone has made some choices. Being able to recognize those choices even in the most successful compositions provides writers / researchers / producers / directors / authors / editors opportunities to see and hear new possibilities for their own voices and voicings.

Fig 3: Screen capture of the full clip of the Jovanna scene as uploaded from the video tape. The clip features two edits; however, only one, highlighted in yellow, is visible above. The other visible edit (a jump cut) occurs at 2:53:19 after Liberty says, "I love my sister to death!" It does not show up as an edit in Fig 3 because it occurred in the camera, not in the editing software. That is, Liberty obviously turned off the camera and then turned it back on to finish the scene.