Conclusions (continued)

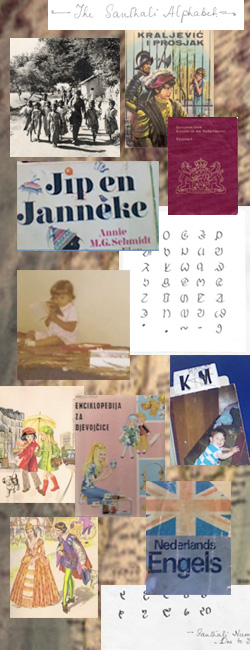

Focusing on literacy narratives can be one of the ways in which we call attention to these material aspects of literacy by studying narratives for their focus on language and place. As Selfe and colleagues note, literacy narratives represent a means through which individuals compose or construct their literate lives, but are also texts through which we can understand the cultural and historical influences on literacy practices of individuals, including place and language. Relying on Mark Zuss’s (1997) notion of métissage, Selfe et al. (2013) suggest that literacy narratives can be sites for métissage, personal transformations that encourage multiple relationships with those from diverse backgrounds and situated within a number of different home, school, social and institutional environments. The women and their literacy narratives interact with these environments in creating places for themselves in their adopted societies.

Reynolds (2004) and the three women in our study also remind us that even in the mobility that characterizes the twenty-first century, most people “live intensely local lives” (p. 89), despite Debleena’s and Lisa’s penchant for travel abroad. This notion demonstrates how the women we feature see themselves differently, as they traverse national boundaries and other spaces, from home to school, or from a home life to child care institutions. Each narrator focuses on the kind of thirdspace Soja offers, describing the prominent places of their literacy narratives as social spaces that in all three cases exist at language boundaries between different cultures. These women view their experiences as different from those of their audiences and their peers, focusing on this boundary crossing as an important aspect of their literacy development.

As these women construct their narratives, they see themselves as outside of and among sometimes many different cultures, influenced by all perhaps but belonging to none. In their transnational experiences, then, building a translingual thirdspace where different cultural experiences and languages circulate becomes an important part of each of their identities. These women position themselves among different languages and different worlds, demonstrating the importance of language, of culture and of place in their literacy experiences. While these narratives represent just three women’s transnational experiences, they demonstrate—through spoken and written words and images—the potential importance that the DALN might assume in representing transnational literacy experiences from a multiplicity of perspectives.