Intersecting Data

Connecting the data in the DALN to other publicly available data can provide users with new ways to view the collective contents of the database and with additional information related to individual narratives in the DALN.

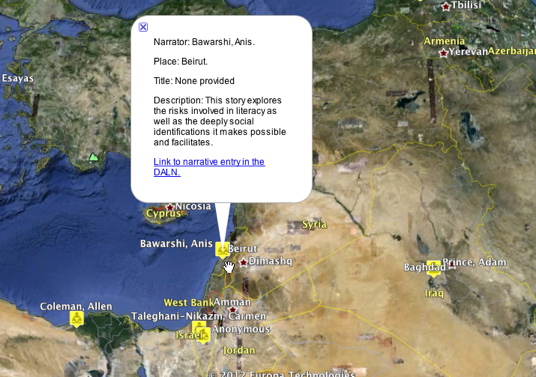

For instance, viewing a representation of the DALN metadata in Google Earth that shows placemarks associated with each narrative for which the contributor supplied geographical information, a student in my class who grew up bilingual and spent part of her youth in the Middle East immediately panned the display to that region and found a narrative by Anis Bawarshi that intersected with her own experience of bilingualism but led her to new realizations about the politics of language during Lebanon's civil war, which took place a generation earlier (see Figure 4).2

Figure 4. Anis Bawarshi's literacy narrative highlighted in a Google Earth view of DALN metadata.

In one sense, the student's experience highlights a major affordance of well-designed search engines: they help you find what you are looking for and/or discover something of interest to you. Yet leading us to what we seek is also a limitation of search engines, insofar as efficient searches insulate us from serendipity effected by "peripheral" returns. Not long ago, academics often expressed nostalgia for "browsing the stacks" in terms of such peripheral discoveries, an effect lost when we search for a title in a library database and are directed promptly to its record (of course, a "shelf position" listing of search results can provide a version of browsing the shelves).

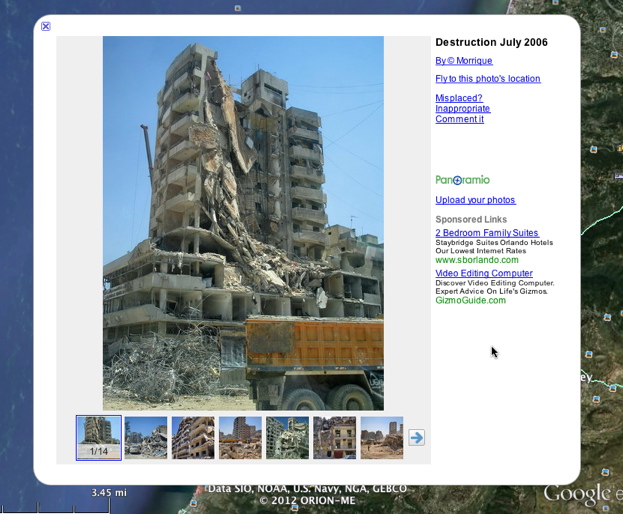

The Google Earth display of the DALN presented the student who scrolled to the Middle East with different sorts of peripheral information. Looking for literacy narratives from Lebanon archived in the DALN, she would also have seen (though I do not know whether she explored) other information mapped in the same space: cities, political boundaries, geographical features, monuments, parks, businesses, user-supplied photographs, and so on. If she browsed that information, she might have found a user-contributed photograph showing destruction resulting from the "July War" of 2006 and connect her generation's experiences more directly with those of Anis Bawarshi (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Images of destruction in Beirut, July 2006, posted in Google Earth via Panoramio by Morrique.

Of course, connections among data sources have always been available to knowledge seekers. But going to the library to conduct research on a topic that arises in a literacy narrative one downloads from the DALN is qualitatively different (not superior or inferior) to connecting the DALN's metadata directly to the data represented in Google Earth, in which case the DALN metadata is embedded in the same search interface as all of the other data represented in Google Earth. Of course that data reflects the interests and motives of the designers and users of Google Earth, but external sources of information and information are still available to readers appropriately skeptical of any single source.

But this example raises other issues more germane to our inquiry and unique to the DALN than the quality or limitations of the data contained in Google Earth. Confronted with DALN data plotted against an interactive cartographic representation of the Earth, a representation scalable from the entire globe to street view, users might assume that they are viewing an equally comprehensive and geographically accurate representation of the DALN. However, in at least five ways, the view of the DALN currently available for display in Google Earth does not fully or unambiguously represent the contents of the archive.

First, because it requires significant manual "massaging" of DALN metadata to import it into Google Earth, the Google Earth view of the DALN is not up to date. Rather, it represents a snapshot of the database at a particular time. Secondly, because contributors provide geographical information of different specificity, from a country to city or neighborhood, but Google Earth translates all such information to a single latitude-longitude pair for display, most of the placemarks in Google Earth for DALN narratives are approximations. For instance, a visitor thinking to explore narratives by Israeli citizens might click on a DALN place mark in Israel, only to discover, as is the case with at least one narrative, that the contributor had tagged her narrative with the term "Middle East," and Google Earth represents the region at that level with a place mark located in Israel. Thirdly, many narratives associated with a given place are not depicted in the Google Earth view of the archive because the narrator did not provide geographical information or did not provide it in the fields used for this representation. Fourthly, a search for "Middle East" in the full text search on the DALN site turns up (at this writing) at least one narrative that doesn't appear in the Middle East in Google Earth because the contributor entered that phrase in the subject field rather than one of fields for geographical information. (Similarly, some narratives may contain a particular term or phrase in the narrative itself but not in any of the metadata, and other narratives might turn up in a full text search for "Middle East" because the phrase appears in a transcript of a video narrative—remember, however, that not all video or audio narratives are transcribed). In short, reading the DALN database through the geographical, data-rich lens of Google Earth offers the possibility of extending the information in a given narrative, but it also poses unique interpretive challenges that arise when we map one database onto another.

Finally, the latitude/longitude data acquired in the process of georeferencing the geographical information supplied by narrators also allows us to quantify some geopolitical characteristics of the DALN.  In the DALN_SeparateLatLong_111120.xls file included in the DALN Database Toolkit, a simple sort by latitude and longitude shows that, of the 915 narratives for which we have georeferenced data, 4 (0.44%) refer to the Southern Hemisphere, 911 (99.56%) refer to the Northern Hemisphere, 57 (6.23%) refer to the Eastern Hemisphere (defined here as -20° W through 160° E and encompassing all of Africa and Eurasia), and 853 (93.22%) refer to the Western Hemisphere. Clearly, reading the DALN database in this way reminds us that we can pursue relational reading across narratives in certain areas of the globe more extensively than in others.

In the DALN_SeparateLatLong_111120.xls file included in the DALN Database Toolkit, a simple sort by latitude and longitude shows that, of the 915 narratives for which we have georeferenced data, 4 (0.44%) refer to the Southern Hemisphere, 911 (99.56%) refer to the Northern Hemisphere, 57 (6.23%) refer to the Eastern Hemisphere (defined here as -20° W through 160° E and encompassing all of Africa and Eurasia), and 853 (93.22%) refer to the Western Hemisphere. Clearly, reading the DALN database in this way reminds us that we can pursue relational reading across narratives in certain areas of the globe more extensively than in others.

Explore the Data: Google Maps

Explore the Data: Google Maps

Using the map below, users can explore literacy narratives in connection with publicly available Google Map data. The DALN_SeparateLatLong_111120.xls file contains this spatial data in a form that can be used in an application such as Google Earth. [Note: If the live Google Maps view is no longer available, you can view a screenshot of DALN data displayed in Google Maps here.]

View A Geographical View of the DALN in a larger map

2. Using Google's Refine, a software tool designed primarily for cleaning up messy data, we can reconcile a location field in the metadata for each DALN narrative with the corresponding place in Google's database and then retrieve the associated latitude and longitude for each narrative from Google—a process called georeferencing. With that cartographical data in our file, we can then translate selected fields from the DALN database into a KLM file, the application programming interface (API) that allows users to prepare georeferenced data for viewing in Google Earth and Google Maps.

Given the inherent messiness of the self-reported data in the DALN, articulation with external data doesn't come easily. First, place names must be spellchecked in order to ensure that corresponding values can be found in Google's database. Second, the various fields in the DALN database that refer to location (see the list below) have to be normalized to chose the most specific location from several "nested" values. For instance, if a contributor filled out the "state or province" field with the value "Texas" and provided additional spatial information such as "Houston, TX" in another field, we would copy the more specific information to a "location" field that we intend to look up in Google Earth.

Spatial fields in the DALN database:

- dc.coverage.region[]

- dc.coverage.region[en]

- dc.coverage.region[en_US]

- dc.coverage.spatial[en]

- dc.coverage.spatial[en_US]

- dc.coverage.stateprovince[]

- dc.coverage.stateprovince[en]

- dc.coverage.stateprovince[en_US]