Plagiarism, Peer Response, and PeerMark

PeerMark emphasizes the positives in its marketing messages, but a closer look shows the limitations of this technology as well. Like the touted advantages of GradeMark, PeerMark centers on six advantages of its service, including improved critical thinking and easy distribution of papers for review.

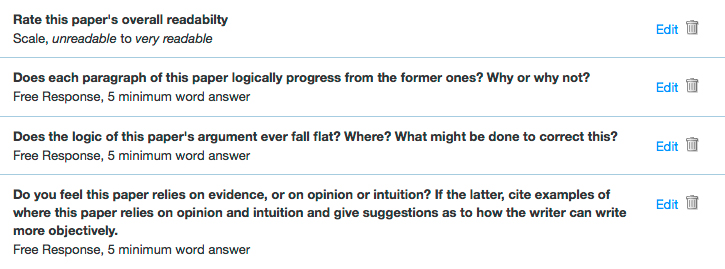

The screenshot below shows how the PeerMark service by default focuses on questions that pertain to a particular genre of writing: thesis-driven, argumentative researched essays. These default embedded questions also illustrate how PeerMark and GradeMark are far from neutral technologies but instead showcase the values and assumptions of their creators. Questions like ”Does the logic of this paper's argument ever fall flat?” invoke an understanding of writing as argument-driven, often where the thesis is immediately discernible to the reader (frequently in the last lines of the first paragraph). These questions imply that the kind of writing that will be uploaded to the system is research-based, argumentative, thesis-driven writing, exactly the kind of writing that lends itself easily to patchwriting and plagiarism.

Perhaps anticipating instructors' concerns about generic research papers, Turnitin.com's FAQs state that

Some educators attempt to solve the copying problem by designing assignments that are ”plagiarism-proof.” For example, rather than asking students to write a research report about icebergs (which is easy to cut and paste from web sources), a teacher might ask them to write an autobiography as if they were an iceberg. ... But eliminating all opportunities for plagiarized material is difficult. Traditional research papers, for example, are an essential part of many curricula and are inherently vulnerable to plagiarism (”Turnitin FAQs,” 2012).

The assumption here seems to be that plagiarism only happens through misappropriation of sources—that having students write autobiographies from the point of view of icebergs should be enough to sidestep possible plagiarism. Turnitin's answer misses the point: so-called "plagiarism-proof" assignments work best when they are local and contextual, when they speak to the interests and concerns of the students, and when they have the potential to make an impact in some way for the student, the classroom, the community, etc. Writing about icebergs isn't the issue; the way writing itself is framed (as a task, a chore, or an opportunity) is crucial. Turnitin's response is one informed by the dominant narrative of plagiarism rather than the complexities offered by current composition research.

Returning to the PeerMark screenshot above, the default responses also assume that students will be able to discern the logical progression of paragraphs, for example, without additional assistance from their instructor or the PeerMark system. Much like GradeMark's service offers commentary that is oddly distanced from the robust, one-to-one nature of the composition classroom, PeerMark seems similarly distanced from the complex, often messy kind of peer response most of us hope to evoke in our classrooms and writing centers. Again, an instructor can certainly tweak the system to better match her pedagogy, but that kind of adjustment takes time; the level of commitment necessary also raises an important question: Aren't there better ways of doing this, ways that are not embedded in a system that focuses on plagiarism detection? (PeerMark and GradeMark are part of the OriginalityCheck system and cannot be used separately.)

Despite the fact that current plagiarism crisis discourses do not necessarily correlate with measurable increases in incidents of plagiarism, and despite the fact that no one technology is magically equipped to address all of our pedagogical needs (if we simply elide our worries about the ethical handling of the intellectual property contained within its archives or the money required to stay out of the database), companies like Turnitin are reaping the monetary rewards of cultural anxieties. This widespread reliance on plagiarism detection technologies has elicited recent work critiquing their use, particularly their impact on the classroom (Marsh, 2004; Castner, Donnelly, Ingalls, Morse, & Stockdell-Giesler, 2006; Gillis, Lang, Norris, & Palmer, 2009; Purdy, 2009). In one of the earliest pieces to concentrate specifically on Turnitin.com, Bill Marsh (2004) interrogated how the system, as a “corporate solution to a nagging pedagogical problem,” socializes students to become docile subjects in the writing classroom (p. 428). They become complicit in the technology’s demands to submit their intellectual property. Following Marsh’s discussion of docile submission, Rebecca Ingalls (2006) noted that power differentials in the classroom may make students hesitant to speak up against the use of plagiarism detection services even if they have valid concerns (n.p.). Students uninformed about Turnitin’s practice of gathering and maintaining a database of original papers might submit to pedagogical practices regarding plagiarism that they might not if they were informed more fully.

Moving beyond the widespread concern over Turnitin’s use of the intellectual property uploaded to its database, others have expressed fears about the site’s usefulness as a plagiarism detection service (Denhart, 1999; Royce, 2003; Bishop, 2006; Gillis, Lang, Norris, & Palmer, 2009; Purdy, 2009). In short, can Turnitin.com deliver what it promises: an easy-to-use site that will provide an “originality report” for each paper uploaded? Can it truly improve the student writing cycle by preventing plagiarism and providing rich feedback to students (“Turnitin for Educators,” 2012)? Can it actually assist instructors in preventing academic dishonesty in their classes (without relying on coercion, a mutual atmosphere of distrust, and/or threats)? Thus far, research has surmised that the site is limited in its effectiveness in pointing out suspected plagiarism and its ability to teach students about plagiarism without embedding those messages in a framework of guilt until proven innocence. And of even greater concern, Turnitin reifies individual authorship through services like iThenticate, which “provides scholarly researchers, publishers, and Masters and PhD candidates peace of mind they are publishing original content,” and Turnitin For Admissions, which ”helps schools admit the right candidates while saving them time and resources verifying the originality of admissions materials” (”iThenticate for Researchers and Publishers,” 2012; ”Turnitin for Admissions,” 2012). In each instance, originality is aligned with peace of mind: that one's work, or even one's self, is laudable and correct.

index ![]()

![]() the specter of internet plagiarism

the specter of internet plagiarism ![]()

![]() the turn to turnitin.com page 1

the turn to turnitin.com page 1 ![]() page 2

page 2 ![]() page 3

page 3 ![]() page 4

page 4 ![]() page 5

page 5 ![]() page 6

page 6 ![]()

![]() authorship and anxiety page 1

authorship and anxiety page 1 ![]() page 2

page 2 ![]() page 3

page 3 ![]() page 4

page 4 ![]() page 5

page 5 ![]() page 6

page 6 ![]()

![]() critical assessment

critical assessment ![]()

![]() references

references