The Classroom: Early Findings

- Many students did not alter or only minimally altered the messages sent using different technological applications and tools.

- A number of students produced text messages that were more successful than their corresponding emails.

- Most students took my directions literally and sent very simple messages, rather than crafting messages likely to generate useful feedback, particularly given the constraints of each technological tool in use.

- Student writing displayed little evidence of audience awareness, regardless of communication technology used.

Finding One:

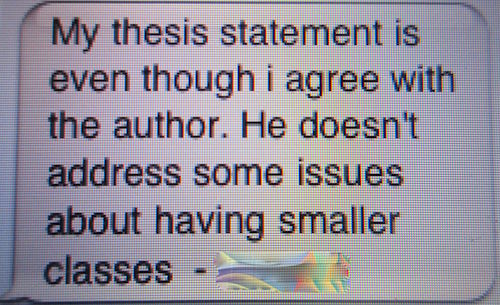

Most students sent text messages that contained their thesis statement and (possibly) a simple, general request for help. One student sent this message:

A number of student emails varied little from their original messages sent via SMS. For example, the author of the text above wrote this (and nothing else) via email: “my main idea is even though i agree with the author about having smaller classes, he doesn't address the issues about having them.” Like this email, others did not use complete sentences or standard punctuation, composing emails that followed the conventions of texting rather than electronic mail. The emails rarely provided sufficient context for the reader; further, they rarely included more specific information or requests, despite the greater capacity for elaboration (in contrast to SMS) offered by email. Most students did not identify themselves in the text or include a salutation or signature.

Finding Two:

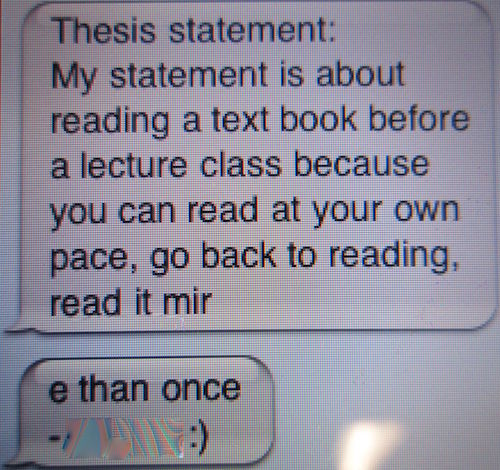

However, when there was variation between text messages and emails, students sent more successful text messages. For example, one student wrote via text:

This is what he/she sent vie email: “My main idea is how reading before your lecture class can help you with the marterials [sic] in your lecture class.” This was the entirety of his/her email. Like this email, most emails did not include a salutation or signature, mirroring the conventions of texting. Interestingly, while his/her first message, the text message, does lack some needed context it includes more specificity and provides more information to the reader. Further, the text message, ironically, actually displays greater command of the conventions of Standard English, using capitalization and punctuation more effectively (though still not perfectly). This student was not alone: In more than one example (and counter to what we might expect), observance of the standards of written English decreased as students moved from text to email, as can be seen in the example from the previous paragraph. Indeed, the quality of the content of the text messages was generally better than that observed in the emails, particularly in terms of the questions asked by students. Another student sent this message (and nothing else) via email: “The mail idea is immigration and the Dream Act”.

From the student perspective, it isn't surprising that the text messages were either the same or perhaps even better than the emails they sent. If the work they did in order to send the text message was sufficient, it isn't necessarily clear why they would need to do any more for the email they send directly afterwards. If it worked for a text message, why not an email?

Finding Three:

Students took literally the directions provided, producing messages without making rhetorical decisions based on purpose, audience, or technological tool used. As noted above, students were asked to send a message (using SMS via mobile device and email via desktop computer) that contained 1) a draft thesis statement and 2) a request for help. Responses fell into three categories: messages that didn’t follow the directions given, messages that included a thesis statement and a simple request for help, and messages that followed directions and included a request for help specific enough to produce a useful response. Many students didn’t follow the directions completely: In fact, the majority of students actually only sent a thesis statement, without a request for help. Almost all students who followed the directions did so in a very literal manner. Only two students produced messages that followed the directions with a clear attempt to fulfill a particular purpose; these students included a request for help with questions specific enough that the writer could reasonably expect to receive a specific and possibly helpful answer. For example, one student wrote, “The main idea of my paper is why college athletes set themselves up for failure Would you be able to recommend a couple sources for me?” While the email lacks any further contextualization or elaboration, and fails to include decorum-related email conventions (such as a salutation or signature), it does include a question that could be answered in a manner that might be helpful to the student.

It should be noted that from the students' point of view, these directions were likely somewhat vague. They were required to make a number of assumptions and rhetorical choices based on very simple directions. These directions were purposefully simple because of the nature of the experiment; with more instruction, students would have likely been much more successful.

Finding Four:

Generally speaking, student writing displayed little attention to audience, regardless of the specific technological tool used. In many cases, both emails and texts:

- lacked pertinent basic information (such as the identity of sender);

- did not include an appropriate level of contextualization; and

- failed to include a consideration of decorum, given the audience and situation.

Most of the text messages sent lacked enough identifying information; only a phone number served to identify many of the messages—not enough information given for the specific situation (texting a professor that may or may not know the name of the text messager, but certainly does not know the phone number of said sender). The emails also lacked much in the way of identification—only one student out of the entire group signed an email.

Beyond lacking basic identifying information, all of the messages failed to provide enough contextualizing information for the audience given the rhetorical situation. This outcome relates to Finding Three—students followed the given directions literally. Since they weren’t asked to provide context or background information that might be helpful to the receiver of the message, they didn’t provide it.

Finally, students did not follow standard conventions of correspondence; none of the messages used the language of decorum to connect with the audience. These conventions of correspondence are general, but they are certainly expectations common within an academic discourse community. Professors and staff at a university generally expect to receive messages with a “polite” salutation, a consideration of the reader (insofar that basic or contextualizing information is included), and some kind of identifying signature. An inclusion of some kind of thanks is also appreciated, though not necessary; at the very least, including a “thank you” may be a savvy rhetorical move on the part of the sender. Given that many of us have heard stories of professors who won’t answer student emails if they don’t follow standard decorum, this last issue is of particular importance—not as a moral issue but as a practical one. It is a problem if students aren’t able to get a response from instructors and staff because they have failed to produce decorous enough electronic epistles, whoever gets the blame.

Gee (2008) notes that concerns over a literacy crisis may, in part, be connected to a failure to distinguish between basic literacy (the ability to decode and encode written messages) and the literacies of school. As Gee points out, just about everyone has basic literacy (he puts the number at 95% in 1985) (p. 32); it is only when people are asked to complete more complicated school-like tasks that we see literacy rates drop. While Gee originally made these observations in the early nineties, his description of the split between basic literacy and academic literacy is relevant to understanding today’s supposed literacy crisis. What is different from when Gee first noted this issue a generation ago is the role that public and private electronic communication has on the split between basic literacy and academic literacy. It is important to note that this experiment does not conclusively prove that the students involved in this study, or college students in general, cannot adapt their rhetorical choices when they move between tasks in an electronic environment that requires basic literacy and tasks that require academic literacy. The experiment described above does blur the lines between academic literacy and the functional literacy needed to communicate personal messages in a digital environment. While Lunsford (2010) compares examples of students’ personal communication with examples of professional communication, this experiment asked students to complete an academic task using an electronic tool (a mobile phone) normally used for personal communication. This study, then, is not necessarily representative of the ability of students to navigate effectively between personal and academic rhetorical situations in an electronic environment. Further, it may not be surprising that students did not greatly alter their rhetoric as they moved from SMS to email, given that the context surrounding the two linked communicative tasks was artificially constructed, rather than an authentic personal or academic situation. However, when students were asked to complete an academic assignment, which required school literacy, they had difficulty addressing differing audience expectations when shifting from one electronic tool to another: a significant finding.

In other words, even though students were given a “school” assignment, this experiment suggests that they failed to demonstrate a strong grasp of “school literacy” when communicating in either SMS or email. While this study does not necessarily compare student ability when composing for personal and academic purposes, it does suggest, that, at least for this group of students, corresponding in accordance to academic expectations while using electronic tools normally reserved for personal communication is challenging. I would predict that Lunsford’s students at Stanford, however, would be less challenged by these tasks. Further study on this issue should include a comparison of student responses to this study from a differing range of institutions; it would be particularly fruitful to replicate the above experiment and compare data collected from institutions like mine, where over 50% of students are first-gen college students, with data from institutions like Stanford, where most students come from the upper echelons of society.

As we consider Trimbur’s (1991) and Gee’s (2008) accounts of literacy crisis narratives in relation to our current digital age, it is essential that we maintain the concern for class and difference that was central to both of their accounts. With this in mind, it may be necessary to add a third category of literacy to the discussion of “basic” and “school” literacies begun by Gee. The role of “cultural literacy” should be examined in relation to our discussion of the ways that differing populations of college students navigate electronic communication practices in an academic environment. The critique of students who use hyperliterate language in academic or professional settings can be likened to the critique of those students who wish to maintain the right to their own language (as supported by the NCTE and CCCC) in academic environments and beyond. Those who advocate for the importance of cultural literacy—familiarity with the “classics” and facility with dominant English—maintain that such a right does not exist, and that a defense of the right to, for example, use African American English (AAE) or Spanglish in an academic/professional setting will lead to the weakening of society brought on by an increased acceptance of the attitudes and practices of the lower classes.

Seen this way, the deployment of hyper writing in such settings may be usefully examined as related to the use of code switching (Auer, 2002) or code meshing (Young, 2009) strategies. This isn’t to suggest that students necessarily should have the right to use text message jargon in their academic essays. Instead, I would suggest that the deployment of hyper writing in an academic setting could be better understood as an example of students switching or meshing codes within a discursive context where the use of such codes is not conventionally seen as appropriate, rather than evidence of the rapid decline of literacy in the digital age. The critique of this kind of discursive activity, is, however, analogous to the attack on both code switching and meshing, and Students’ Right to Their Own Language, by proponents of cultural literacy. Attacks on the use of home dialects and the use of hyper discourse (e.g., SMS jargon) in the classroom are both based on the fear of the Other—the fear that widespread evidence of either kind of discursive activity suggests that the true, pure, culture of our society is being weakened from within by those, by dint of race or economic standing, simply don’t have the "class" to know better.