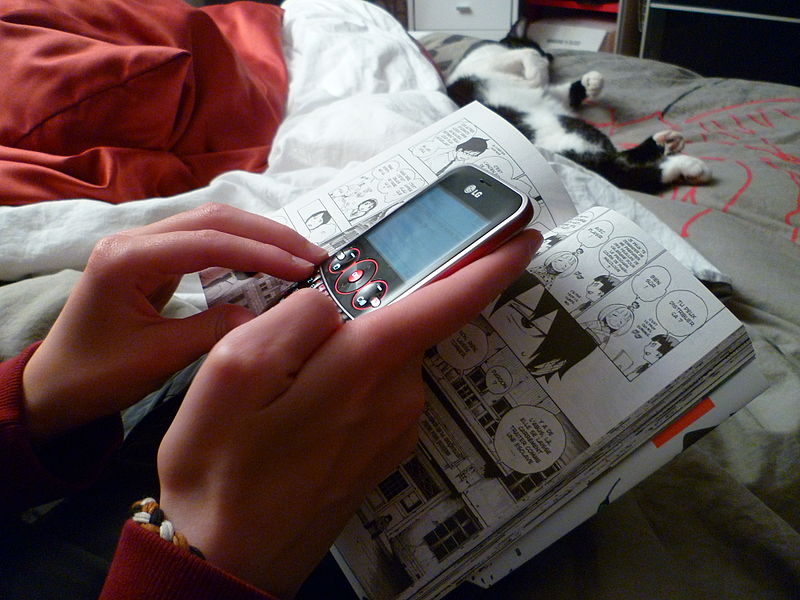

French teenage girl texting while reading Blue Exorcist by Olybrius.Used under CC BY 3.0 license

The Question: What is the Real Literacy Crisis, and How Should We Respond?

It is essential that we develop an understanding of the connection between the political rhetoric of the network culture (which is produced and disseminated by individuals who, because of their privileged positions, are some of the highly educated and literate members of society) and the text messages and emails our students send, which supposedly indicate we have a literacy crisis on our hands. Following Tizianna Terranova (2004), who structured an argument about politics in the network culture around several propositions about recent shifts in communication theory, I would like to offer several propositions. These propositions respond to literacy practices in the current mediated and mobile communicative environment.

Propositions:

1. Many developing writers are egocentric; mediated and mobile communication technologies reinforce that egocentrism.

As Sondra Perl (1979) noted as composition was just emerging as a field, developing writers are, in her words ”egocentric" (p. 332); that is, they assume that the audience is on the same side as they are. Moreover, developing writers assume they are speaking or writing to someone with the same world view and therefore with similar expectations about communication. In our network culture, this egoism may be encouraged or even exacerbated by the hyper writing and reading that happens on social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter. These sites are based on individuals constructing digital subjects and then maintaining those identities by pushing information outward regardless of whoever might be a “friend” or “follower”; the assumption being that whoever is in one’s network is “on the same side” as the sender. This disregard for audience is paralleled and reinforced by public political discourse that rarely connects to those of an opposing political persuasion; instead, such discourse is created by and for those who are ideologically predisposed to whatever message being sent. This is further reinforced by the use of media outlets (both television, online and print) that exist only to communicate to particular segments of the population (like Fox, Talking Points Memo, etc.). What results is a digital echo chamber. I detail these consequences below in relation to my third proposition.

2. Mobile, hyperliterate, communication practices, like noise, reinforce the return to the minimum conditions of communication.

Tweets, texts—like PowerPoint bullets—are brief pieces of information/messages designed to cut through noise and reach the receiver directly. Students are comfortable communicating in this hyperliterate, “on-the-go” way; they have more difficulty recognizing when the rhetorical situation demands something more than just making contact.

3. Public political discourses and private mobile discourses are affective; both are shaped by bodily perceptions and interactions within and between the mediascape and physical space.

The ways our students communicate are connected to the physical tools they use. As Terranova (2004) notes, our physical interaction with communicative tools (via keyboards, touch screens, hands-free devices) helps create a constant state of distracted perception. It may be that the affective, embodied impact of our ongoing use of technological tools (mobile and otherwise) is connected to the increased tendency to communicate in hyper writing, through chunks of writing in bullets, tweets, texts and posts. The tendency to communicate in these ways may also be connected to affect through the public platforms through which we interact and receive information.

All of this leads to a situation wherein the writing that many of our students are most comfortable producing can be considered an act of hyperlitercy: it is brief, to the point and often lacking in the niceties of “civil” discourse. In many cases, information is communicated clearly but without tact, and without an appropriate amount of rhetorical awareness. I would argue, however that cries of alarm regarding the decline in the literacy of our youth are less concerned with rhetorical savvy and more interested in the (lack of) cultural literacy and the “civilized” manners of those who are supposedly texting and Googling themselves into stupidity.

Niall Ferguson (2011) provides some direct evidence of concerns about cultural literacy in a 2011 issue of Newsweek. He writes that half of today’s teenagers don’t read books and that this matters for two reasons:

First, we are falling behind more-literate societies… But the more important reason is that children who don’t read are cut off from the civilization of their ancestors… So take a look at your bookshelves. Do you have all—better make that any—of the books on the Columbia University undergraduate core curriculum... Let’s take the 11 books on the syllabus for the spring 2012 semester: (1) Virgil’s Aeneid; (2) Ovid’s Metamorphoses; (3) Saint Augustine’s Confessions; (4) Dante’s The Divine Comedy; (5) Montaigne’s Essays; (6) Shakespeare’s King Lear; (7) Cervantes’s Don Quixote; (8) Goethe’s Faust; (9) Austen’s Pride and Prejudice; (10) Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment; (11) Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (p. 11).

And so, as Trimbur (1991) argues, new literacy crises appear in cycles, and we have another literacy crisis on our hands. While it is different from the one he was writing about in 1991, at its root, at least partly, it is the same. When we decry the new generation’s lack of literacy, we are more concerned with how “civilized” they are, as the evidence above suggests.

The results of the experiment described in the “The Classroom” bear this out. The students were all, by Gee’s (2008) definition, literate. That is, they could compose and send written messages based on a set of directions. They were, as Gee suggests, less successful when it came to what he calls “school literacies;" they often failed to apply critical thinking and decision making to composing the messages they sent. But what I would suggest ends up being the biggest cause of concern to those who raise the alarm over the current crisis in literacy is the fact that basically none of the messages that the students sent were grammatically correct or polite. That is, they contained none of the niceties that civilized, culturally literate correspondence is supposed to contain. The messages, both texts and emails, did not address the receiver at all, much less with a “Dear Dr. So and So.” The messages lacked basic information that would have demonstrated a consideration of the difficulties the audience might encounter in responding. They did not include identifying signatures, much less a modicum of gratitude or gesture of thanks. It is this lack of civilization, of politeness, of decorum, that I believe most truly upsets those who express alarm over declining literacy brought about by the use of current technology. It isn’t that our students don’t know how to communicate effectively anymore because of the technology, it is because they don’t know how to communicate properly (that is, in a decorous way). In fact, given the conventions of the current social and mobile communication platforms now in use, the generation in question communicates pretty effectively—they just do so according to the standards of “hyperliteracy,” following norms established by the technology and their own social cohort. And their lack of tact, politeness, or civility is reinforced by a media that rarely rewards complex messages, much less compassionate ones.

And so, while it is fashionable to suggest that Google/PowerPoint/Twitter is making our children stupid and causing a crisis in literacy, when one investigates further it becomes clear that such claims are rooted in fears similar to those that drove previous outcries over a decline in literacy. As Trimbur (1991) argues, the literacy crisis was driven by concerns that middle class students would devolve to the supposedly deficient communicative ability of those in a lower class or different race. A decade later, and again more recently, Gee (2008) discusses the role of xenophobia in popular alarm over literacy crises, pointing to rising immigration being at the root of such concerns, rather than any actual loss of communicative ability. And now, in 2013, the outcry is over technology and the ways it is creating new generations of illiterate children and students. But at its core, we see a similar set of fears: A concern that our youth is less civilized, less respectful of the values and cultural manifestations of proper society, and that this lack of “Culture” is demonstrated in everything from text messages to Facebook posts, points to the erosion of Western Civilization itself.

While those who drive the latest popular literacy crisis discourse may be lamenting the dilution of traditional Western culture and attempting to revive and reinforce, through literacy, demarcations between high culture and low and between the upper classes and lower, the current media environment plays a role in producing and reinforcing this hegemonic organization as well. Those who warn about the increasing stupidity of text-messaging youth are seeking to maintain the cultural, economic, and political hegemony of the elite; this hegemony is also manufactured through the representation and practice of political rhetoric in the network culture. Those who wish to challenge this status quo, then, should not worry over the propensity of students to use SMS jargon, but instead focus on their students’ ability to argue critically and compassionately, using whatever tools or genres are appropriate to the situation. Instead of concern over correctness and “civility” (as civilization is an inherently imperialist concept), we need to be focused on critical thinking and compassion. Communication in the network culture tends to reinforce division amongst classes and ethnicities through the reliance on affect and segmentation of audience, exacerbating our fear of the Other, and causing a crisis of understanding. This crisis parallels what Trimbur noted in 1991 was (and continues to be) the real crisis in literacy: the systemic division and exclusion of those of a certain race and class on the basis of literacy itself.

How then do we as writing teachers and rhetoricians respond to these actual crises? It is essential that we develop and implement pedagogical frameworks for composition programs that enable students to practice hyper writing and hyper reading in connection to other forms of communication, including academic discourse. Students need to be able to understand and experience the connections among their personal hyperliterate practices, such as text messaging and the kinds of discourse they are expected to produce in the college classroom and beyond. Mary Lea and Brian Street’s (1998) articulation of “academic literacies” as well as Johnson-Eilola and Selber’s (2009) conception of C3T are both useful frameworks for the effective incorporation of hyperliteracies into the composition classroom.

As noted by Lea and Street (1998), an AcLits or Academic Literacies approach to the teaching of writing in higher education differentiates between three models of writing pedagogy: study skills, socialization and academic literacies. These authors suggest that the academic literacies model draws from the other two models, but that it is best able to effectively address student writing. In a manner similar to James Berlin’s social epistemic rhetoric, AcLits suggests that writing must be researched and learned in a way that takes into account “institutional practices, power relations and identities” (Russell et al., 2009, p. 400). The academic literacies approach operates on the epistemological assumption that knowledge and discourse is a social process and that discourse is always ideological. According to Lea and Street, an AcLits approach, in contrast to the study skills or academic socialization model, suggests that writing cannot be reduced to a single, universal or transferable process. This model therefore insists that students learn about the connections amongst the discourse of the academy and the power relations that comprise the institution itself. Further, this model of writing pedagogy operates on the premise that students best learn to write for an academic audience, when they can connect their ownpersonal literacy practices to the discourse and institutional practices of the academy (Ivanic et al., 2008).

The experiment detailed in the The Classroom section of this chapter not only functions as a study of the hyperliterate practices of our students, it’s also an example of a classroom activity, which engages students in hyper writing in a manner that fits the AcLits model of writing instruction. Students are asked to communicate in a classroom setting with an instructor, first sending the instructor a text message, and then sending an email with the same information and/or question. Examples of both the student text messages, as well as the emails, are then analyzed, compared, and discussed by the class in relation to 1) expectations for appropriate communication in an academic/professional setting, 2) the importance of considering audience and purpose when choosing and using an electronic tool for communication, and 3) the role of power relations in personal and academic correspondence. This activity provides an opportunity, following the AcLits model, for students to use hyperliteracy practices, normally reserved for their personal daily lives in the composition classroom; it also promotes student engagement with these practices in relation to the systems of discourse and power that comprise the academy. Finally, by engaging students in personal and academic discourse, AcLits promotes a model of argumentation as inquiry, enabling students to move beyond the kinds of binary, “hot button,” political debates that tend to reinforce difference and foreclose on a complex and compassionate approach to communicating with those who have diverse perspectives and backgrounds.

The activity described above is also consistent with the C3T approach to writing instruction advocated by Johnson-Eilola and Selber (2009), insofar as it encourages students to use current mobile communication tools in a classroom setting, and in so doing, demonstrating the value of hyperliteracy practices, rather than dismissing such practices as less than or even harmful to the conventional literacies of school. Johnson-Eilola and Selber propose an approach to composition that asks students to consider four factors when deciding how to communicate: Context, Change, Content and Tools. In any given rhetorical situation, these four factors should be taken into account and used to make rhetorical decisions. C3T takes things a step further than the pedagogy exemplified by the activity described in the “Classroom” section, as it provides a framework for completely rethinking the way that we teach college composition. We can no longer effectively teach composition by beginning with the development of curricula focused on the academic genres and cultural content that we believe students must learn, and then adding multimodal assignments to supplement the academic or cultural content at the heart of this curricula. Instead, as the C3T framework suggests, we must start with a problem and ask students to address this problem by using the communicative tools of their own choice, and by producing texts in whatever genres they determine best match the problem. Only when we as educators articulate the value of hyperliterate practices and argue that they are now essential to the successful learning of the literacies of school—in a direct rebuke to those who decry text messaging as a harbinger of the decline in cultural literacy and destruction of civilized society—will we be able to challenge the current crisis narrative and address the ways that literacy continues, in the twenty-first century, to be used as a means to divide and oppress.

References

- Agger, Michael. (2010). The internet diet. Slate.

- Auer, Peter. (1998). Code-switching in conversation: Language, interaction and identity. London: Routledge.

- Bloom, Allan D. (1987). The closing of the American Mind: How higher education has failed democracy and impoverished the souls of today's students. Simon and Schuster.

- Brennan, Teresa. (2004). The transmission of affect. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Carr, Nicholas. (2008, July 1). Is Google making us stupid? The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/07/is-google-making-us-stupid/306868/.

- Carr, Nicholas. (2010). The shallows: What the Internet is doing to our brains. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Conference on College Composition and Communication. (1974). Students’ right to their own language. CCC, 25(3), 1–32.

- Donaldson, Patrick. (2006, April 18.) “Angry professor.” [Online video clip.] Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hut3VRL5XRE.

- Ferguson, Niall. (2011, October). Texting makes u stupid. Newsweek, 158(12), 11.

- Gee, James Paul. (2008). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses (Third Ed.). London: Routledge.

- Gold, David. (2008). Will the circle be broken: The rhetoric of complaint against student writing. Profession, 83-93.

- Hayles, Katherine. (2007). Hyper and deep attention: The generational divide in cognitive modes. Profession, 187-199.

- Hayles, Katherine. (2012). How we think: Digital media and contemporary technogenesis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hirsch Jr, Eric D. (1988). Cultural literacy: What every American needs to know. Vintage.

- Ivanic, Roz, Edwards, Richard, & Martin-Jones, Marilyn. (2008). Giving other literacies a place at college: Learning is enhanced when teachers integrate students' day to day practices. Poster presented at the Teaching and Learning Research Programme Conference.

- Jamieson, Kathleen Hall, & Cappella, Joseph N. (2010). Echo chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the conservative media establishment. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Johnson-Eilola, Johndan, & Selber, Stuart. (2009). The changing shapes of writing: Rhetoric, new media, and composition. In Amy Kimme-Hea (Ed.), Going wireless: A critical exploration of wireless and mobile technologies for composition teachers and researchers (pp. 15-34). New York: Hampton Press.

- Keller, Bill. (2011, May 18). The Twitter trap. The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved January 5, 2015 from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/22/magazine/the-twitter-trap.html.

- Lakoff, George. (2008). The political mind: A cognitive scientist's guide to your brain and its politics. Penguin.

- Lea, Mary R. & Street, Brian. (1998). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. Studies in higher education, 23(2), 157-172.

- Lunsford, Andrea. (2010). Our semi literate youth? Not so fast. Stanford study of writing. Retrieved from https://ssw.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/OPED_Our_Semi-Literate_Youth.pdf.

- Perl, Sondra. (1979). The composing processes of unskilled college writers. Research in the teaching of english, 13 (4), 317-336.

- Russell, David, Lea, Mary, Parker, Jan, Street, Brian & Donahue, Tiane. (2009). Exploring notions of genre in “academic literacies” and “writing across the curriculum:” Approaches across countries and contexts. In Charles Bazerman, et. al. (Eds.), Genre in a changing world (pp. 395-423). Fort Collins: WAC Clearinghouse/Parlor Press.

- Terranova, Tiziana. (2004). Network culture: Politics for the information age. London: Pluto Press.

- Trimbur, John. (1991). Literacy and the discourse of crisis. In Richard Bullock & John Trimbur (Eds.), The politics of writing instruction: Postsecondary (pp. 275-295). Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook.

- Young, Vershawn. A. (2009). Nah, we straight: an argument against switching. JAC, 29(1/2), 49-76.

Photo Credits

The Classroom

- Schnöherr, Maximillian. (2001). Ebook between paper books [Photograph]. Used under CC BY SA 3.0 license.

The Political

- David. (2009). Photo [Photograph]. Used under CC BY 2.0 license.

- Progress Ohio. (2009). Protestors walking towards the United States Capitol during the Taxpayer March on Washington [Photograph]. Used under CC BY 2.0 license.

The Question

- Olybrius. (2010). French teenage girl texting while reading Blue Exorcist [Photograph]. Used under CC BY 3.0 license

The Story

- Autellitano, Saverio. (2006). Reggio Calabria, Santuario di San Paolo [Photograph]. Used under CC BY 3.0 license.

- Murphy, Tom, VII. (2005). Old book bindings at the Merton College library [Photograph]. Used under CC BY 3.0 license.