DIGITAL CREATION: INTO THE NETWORKS

The key argument I want to make here that connects Autumn Stanley’s (1995) work and arguments to the contemporary spaces in which women are inventing and creating is linked to the final point on the previous page: I suspect that women are deliberately avoiding the formal, official, and legal systems in crafting and sharing their work. We have more ability to do so today and to make that work distributed and visible in part because of contemporary digital tools and networked spaces.

Anne Balsamo’s (1996) Technologies of the Gendered Body: Reading Cyborg Women adds to this connective tissue between past research on women and technology and Stanley’s work on the ways women have been erased, forced out of, or marginalized in the intellectual property processes in the United States and contemporary digital and networked work.

Balsamo also studied the history of women and technology, reviewing work studying women’s labor practices, specifically in tandem with technology, and noted:

While these studies on women as laborers are vital for an understanding of the social and economic impact of computers, there is less research available about women’s creative or educational use of information technologies or their role in the history of computing. (p. 145)

If intellectual property is the fruit of a particular type of labor, I would argue that it is not only crucial for us to explore women’s creative and educational uses of information technologies, but that we must likewise interrogate the ways in which women are claiming authorship and ownership with and through information technologies and within digital spaces.

Three examples that are particularly enlightening in helping us understand the ways in which women are engaging in creative and educational work using digital technologies and networked space are those of Christine Tamblyn, Ju Gosling, andAnn Lawrence. These examples likewise provide a launching pad from which we can connect some digital dots and speculate on where intersections between past, present, and future occur—intersections across the historical situating of women and technology, the current work of women in digital space, and the ways in which the intellectual property regime might shape such work. Below I briefly describe each piece; later in this piece, I’ll dig more deeply into how they serve as particularly interesting examples for studying women, new media, and intellectual property issues.)

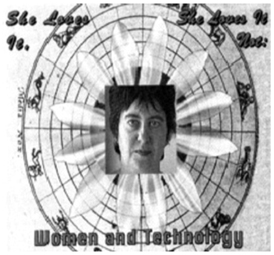

Christine Tamblyn

The first example is from Christine Tamblyn’s (1995; 1997) “She Loves It, She Loves It Not: Women and Technology.” The larger container for this image is a CD-ROM that Tamblyn created, which provides a rich, multimodal, artistic exploration of “human/technological interfaces.” On the CD, Tamblyn includes a set of images of herself; the main image includes a collage of a head shot, a daisy, an astrological chart, and some text.

“She loves it” appears in the upper left. “She loves it not” appears in the upper right.

The author has digitized herself, placed herself within and upon the technology she seemingly has a shifting relationship with. This rich image complicates and questions the relationship of women, nature, and technology. Reflecting on the piece, Tamblyn (1995) noted the affordances of multimedia production, including her inclusion of a range of clips pulled from advertisements and movies, and also argued that a dominant theme in the piece is that “by being excluded from technical knowledge, women have been acted upon by technology rather than interacting with it” (p. 102).

Ju Gosling

Ju Gosling’s web site is my second example. She created the site in response to the absence of the disabled in society and in cyberspace, “either in images or in positions of power.” She argued that the disabled are not only seen as nongendered, they are also seen as sexless and asexual. She asked, “Is it any wonder, then, if we take to replicating digitally in our own mirrors?” (Gosling, 1998, n.p.).

Gosling was diagnosed with Scheuermann's disease when she was 28 and was soon recognized by the British government as, in her words, a “state-certified crip.” After a variety of treatments were tested, Gosling was prescribed an awkward plastic brace that fastened with nylon straps and covered the length of her spine. She described her panic the first time she tried on the brace:

Gosling was diagnosed with Scheuermann's disease when she was 28 and was soon recognized by the British government as, in her words, a “state-certified crip.” After a variety of treatments were tested, Gosling was prescribed an awkward plastic brace that fastened with nylon straps and covered the length of her spine. She described her panic the first time she tried on the brace:

The feeling of being confined made me panic and hyperventilate, and the brace's appearance filled me with horror. Its white nylon straps were made of the same material as the fastenings on my racing dinghy. Its surgical pink surface took no account of ethnic difference: if you were ‘white’, you were pink. Its shape exaggerated my waist and hips while my breasts were the only part of my torso left exposed, creating a feminised, almost Edwardian silhouette. (Gosling, 1998, n.p.)

Initially, she felt claimed by the brace—her identity became submerged in the awkward piece of equipment designed to straighten her spine. Although the brace was intended to help her reclaim herself, her autonomy, she found herself submerged in the brace, by the brace—it became her personality, her identity.

To accept the plastic extension she was forced to wear every day, with the help of an artist friend, Gosling transformed the brace. Gosling (1998) suggested that reclaiming the brace was a move against “medical images ... of surveillance and social regulation, used to classify, discipline and manage the body. I wanted to control my own image, to mark my body in a way which was meaningful to me, and to reject my body's classification by its impairment” (n.p.). One of their priorities as they resculpted the brace was to turn Gosling’s body from an asexualized, disabled body into a different body of desire.

Through the textual and visual material collaged on her site, she described the process of adapting to a spinal brace and claiming her identity as/with a marked body. Gosling layered in multiple technologies in her web essay: physical, digital, and mechanical.

Ann Lawrence

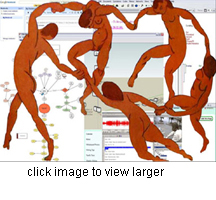

The third example is a digital collage created by Ann Lawrence, a graduate student researcher at Michigan State University. In a graduate seminar, Lawrence produced the piece in response to a prompt asking teachers to represent their teacherly selves through an entirely visual digital collage.

As with Tamblyn's example, the theme of nature and technology is again represented in Lawrence's work, where we have naked bodies twirling around collaged screen captures of different digital spaces—Google docs, an audio file being edited, a diagram, a video clip, and more. The figures are female, but not overwhelmingly distinctly so.

As with Tamblyn's example, the theme of nature and technology is again represented in Lawrence's work, where we have naked bodies twirling around collaged screen captures of different digital spaces—Google docs, an audio file being edited, a diagram, a video clip, and more. The figures are female, but not overwhelmingly distinctly so.

Lawrence's work focuses on the ways in which women write the body and navigate the body as writers; she also examines how women engage with digital technologies as they write and how they anthropomorphize the tools they use to write and the texts they produce. In one of Lawrence's studies, for instance, she described the ways in which the women in one of her writing groups described their draft documents as "abandoned babies" or as "monstrous creatures" (personal communication, October 14, 2008).

One of the goals of Lawrence's work is to encourage the writers with which she works to disrupt the narratives of digital technologies; she argued that "discourses on digital technologies emerging over the past half-century do not appeal to all cultural groups" (personal communication, October 14, 2008).

The Fruit of Our Digital Labor

These three productive and powerful examples help us to begin a response to Balsamo’s (1996) concern about the lack of attention to women’s creative and educational use of information technologies. In each of these works, the creators/authors work across binaries, boundaries, and disconnects—intellectual, physical, and legal—to produce artistic, creative, scholarly compositions (or, we might say, intellectual property).

index | introduction | history | stanley | digital(creation) |

digital(dangers) | ip resistance | conclusions | bibliography

dànielle nicole devoss | devossda@msu.edu