relevance and the pothole paradox

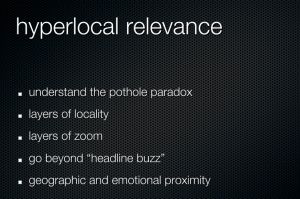

Sites like outside.in and EveryBlock, a hyperlocal site similar to outside.in that calls itself a “geographic filter,” are archives of information about particular areas and provide information such as crime reports and restaurant inspections in addition to aggregating Flickr photos, Yelp reviews, and blog postings. EveryBlock claims to “figure out the relevant places and point you to location-specific items you might not have known about” ("About EveryBlock," 2012, n.p.) are archives of information about particular areas. However, the quality of the information is important, not just the amount or diversity of information. When focusing on hyperlocal content, the relevance of the information becomes paramount in order to avoid what Steven Johnson (2007) called the “pothole paradox.” The idea is that the pothole in front of your home or apartment is a big deal to you, but your friends a few blocks over couldn’t care less. Relevance depends on the scope of a user’s collective identity. For example, a user might be interested in multiple geographic locations because she identifies with, or sees herself as a member of, more than one community. Her collective identity, her sense of belonging, includes multiple groups within multiple geophysical places. EveryBlock provides levels of locality—neighborhood, place, and street—to work from the outside in, allowing users to zoom in and out, depending on the nature of the information and their proximity to it.

Newspapers and blogs are typically organized around time, and they privilege the most recent news. As it says in “The EveryBlock FAQ” (2012), “We're interested in local data that has a date and a specific location” (n.p.). Neighborhood information stays news for longer periods of time, however, than a typical news story that loses relevance fairly quickly. For example, a post mentioning gay-friendly businesses in a particular area would be useful weeks after the post was written, as would information about the location of Chicago Transit fare machines that accept credit cards. EveryBlock, however, makes it clear that in order for information to sustain its relevance, it must go beyond the headline buzz and instead offer users ways to track the conversations, debates, and discussions related to what matters to them as part of their collective identity.

Relevance has both a geographic and an emotional dimension. Steven Johnson (2007) pointed out that crimes, politics, and real estate development, for example, affect a larger population, reverberating more widely than news about pothole repair. Definitions of what is local and what is important or near to me will differ from my neighbors and from my peers. For example, I am interested in the amount of snowfall in Champaign-Urbana where I reside, as well as state budget cuts that will impact how many salt trucks clear the roads, the upcoming Illinois Marathon, and which gas station in town has the cheapest gas. I’m also concerned with the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico because my family and friends still live in Mobile, Alabama. Although I have varying geographic distance from each of these “news items,” these issues share emotional proximity. All of these locations and communities, while not always a part of my daily interactions, are part of my collective identity. Location is only part of what makes information relevant to users of sites like outside.in and EveryBlock.

In previous incarnations of outside.in, participation was encouraged through a featured thread known as “outside inquiry” on discussion boards each week. These threads included questions such as, “What is the most overhyped and overpriced neighborhood in (insert town or city name here)?” and “What (insert town or city name here) building would you most like to tear down?” A small header at the top of each outside.in page listed the outside.inquiry question of the week and invited users to join in the discussion.

Outside inquiry discussion forms which no longer exist.

The outside.in forums attempted to extend the shelf life of information on the site, increasing the potential for relevance. These threads, as well as the discussion forums as a whole, have since disappeared from the site. In its current form, outside.in appears to be more of a news aggregator of hyperlocal content because it has evolved by teaming with publishing companies including The Miami Herald, New York Post, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, properties of the Tribune Company, such as Chicago Tribune, and the Baltimore Sun, as well as bloggers, who use the site to distribute content and drive readership to their blogs.

With less opportunities for users to communicate or create conversation, outside.in's interface no longer provides ways for users to build their collective identity in the ways the site encouraged in the past. The interface, how a site is designed, affects the level of participation, as well as the representation of users throughout the site. Typically, this includes a user profile, avatar, geographic location, email address, and perhaps favorites lists and photos, depending on the website and its purpose. Examining the design of the interface is important to understanding the kinds of participation in addition to the modes of identity construction encouraged by the social media site.

What’s interesting about outside.in is how the changes to the site's design and the loss of many of the features that once encouraged users to contribute content also shift the metaphor from a neighborhood block party where anyone can create a flow of conversation or share news to a neighborhood store where users filter information based on their interests but aren’t necessarily contributing to its production. This shift is significant because it privileges already published work from place bloggers and newspapers. As such, users are able to select information that they determine as relevant to them, the same way they would choose which section of the newspaper they wanted to read. So average users who are not bloggers have no way to contribute content as they once did in the past.

In social media, users build their identities through the structure of the interface but also through their interactions with others on the site. When interactive features and ways for users to communicate, create, and share their thoughts become limited, users become passive receivers of information rather than contributors, leaving relevance in the hands of publishers rather than users. This isn't to say that hyperlocal relevance is only possible when users contribute content but that if journalists and place bloggers are going to be the main contributors of hyperlocal content, then relevance should be a rhetorical consideration of their writing. Otherwise, the hyperlocal trend simply because a buzzword instead of an actual movement of collective identity construction.

June