Implicit Metadata and Ecologies of Ambivalence

In their October 2008 report on the pilot project conducted by Flickr and the Library of Congress (LoC), Michelle Springer et al. provide findings on how and to what effects Flickr members have contributed metadata, or social “tags,” to the LoC’s recently uploaded Flickr content (see Springer, M. et al., 2008). In the “Outcomes” section of the report, the data on social tagging stresses what information Flickr members provide that is not already present in the LoC’s records.[1] The report also explains the process through which a photograph in the LoC’s collections becomes an image on Flickr.

When uploading photographs from its source collections to Flickr, the LoC assigns each image only three tags. One is a “regular” tag, which is always “Library of Congress" (Springer et al., 2008, p. 18). The other two are “machine” tags, which “correlate the [LoC] and Flickr photographs through identification numbers” and “store the association between each Flickr photo and its source photo” in the LoC collections (pp. 8, 18). Other than these three tags, all other tags are “added by the [Flickr] community” (p. 18).

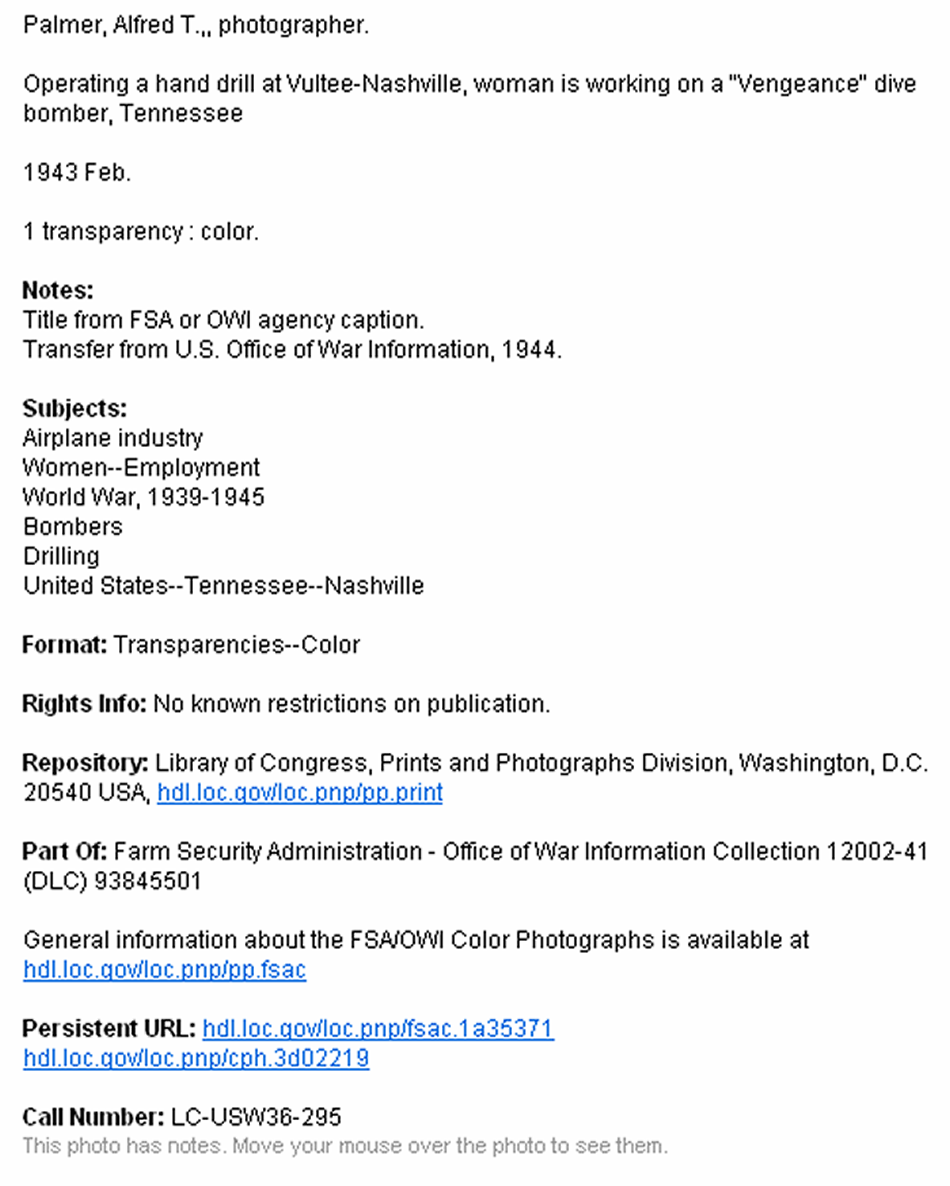

It is also important to note that the LoC’s records are provided beneath each LoC image on Flickr. For example, on the Flickr page entitled, “Operating a hand drill at Vultee-Nashville, woman is working on a ‘Vengeance’ dive bomber, Tennessee (LOC)” (heretoafter referred to as “Rosie”), the following records are listed below the image:

These records follow a template across all LoC photographs uploaded to Flickr. That is, from image to image, Flickr members can assume that information will be provided for each of the classes (e.g., “Format,” “Subjects,” and “Call Number”) listed above. But to return to one of the emphases in the report: what information are Flickr members adding to existing records that will help people learn more about the LoC’s collections? Based upon Springer et al.’s 2008 report, the answer might very well be, “Not very much.”

Indeed, the data in the report implies that, overall, most Flickr members participating in the pilot project tend to tell the LoC what they already know. More specifically, 79% of the tags in the LoC’s Flickr collections fall into two categories: redundant tags repeated or copied from the Library’s records (45% of the tags) and descriptions of “what is seen” in the image (34% of the tags) (Springer et al., 2008, p 21). Here, “what is seen” in the image is descriptive in character and—according to the report—does not include a member’s own commentary, personal knowledge / history, or emotional / aesthetic responses. As such, in the “Rosie” instance, some example tags from this 79% are “drill,” “hand,” “bomber,” “ring,” “nashville,” and “tennessee.” These examples either mirror how the LoC already describes the image or they state what can already be seen by any person looking at the image.

Also, the LoC limits tags to only 75 per image, and “miscellaneous” tags are deleted—an important fact to remember when 79% of the tags were deemed redundant or merely descriptive.[2] Granted, gaining new information from Flickr members is not the sole objective of the pilot project. Other objectives include increasing awareness about photographs in the LoC’s collections and allowing the LoC to gain experience in “emergent Web communities” such as Flickr (Springer et al., 2008, p 4). Nonetheless, a pressing question for a “Standards in the Making” (SITM) approach is not only how metadata influences web traffic and site navigation, but also how people feed back into that navigation, produce new knowledge with metadata, and reconfigure public information accordingly.

What kind of information, then, might be offered by the other 21% of the social tags in the LoC’s Flickr collection? The data in the report suggests that “commentary” (6% of the tags) is the third most common tag category (p. 21). These tags represent people’s value judgments and, in the “Rosie” instance, include “perseverance” and “beauty and grace.” Obviously, commentary tags offer what most metadata standards often do not: overtly ideological qualifiers excluded from more formalist approaches to media and artifacts. True, as scholars such as Bowker and Star argue, all standards are inherently ideological and biased; nevertheless, neither the LoC nor Flickr has a standard for how users should classify their commentary tags (1999). In fact, in the report, Springer et al. refer to the pilot’s approach as “‘hands off’" (Springer et al., 2008, p. 18). As long as the tags are easily understood or somehow correlate with the LoC’s records (or to other descriptions provided by taggers), then commentary by Flickr members is permitted and remains on the page.

Consequently, without an explicit standard in place, these commentary tags might simply foster an amateurish free-for-all, where commentary (such as “perseverance” and “beauty and grace”) correlates with superficial recapitulations of already existing cultural norms and logics. Of course, this reading is extremely pessimistic, and it relies upon a slippery definition of “amateur” and “expert.” Still, as the October 2008 report indicates, Flickr members relied quite heavily on the LoC’s records to compose their metadata tags; and when personal commentary was added, it generally could not be mapped onto a critical practice or specific details about history, geography, or culture (p. 23). As such, 85% of the social tags in the LoC’s Flickr collections could be described as having little informational use to the LoC or other audiences.

Yet explaining away this 85% needn’t be the aim of SITM. Instead, one might attend to what Cory Doctorow (2001) calls “implicit metadata,” which are not explicitly articulated in a given metadata standard, encoded into a certain image or web page, or somehow built into the structure of the Internet. Rather, they are data about people’s online habits and practices: Who reads what? Who links to whose site? How compatible are these two tastes? And so on. Since implicit metadata address these sorts of questions about relationships and practices, Doctorow claims they are in fact more reliable—or they provide people with more useful information—than explicit metadata.

Adding to Doctorow’s critique, I suggest that attending to Flickr’s social tags as implicit metadata affords a means of looking for absences and highlighting ambivalence, especially if the tags are read in tandem with member comments and LoC records. For an example from the LoC’s collections, consider how race functions in the Rosie instance. Under “Subjects” in the LoC’s records, there is no mention of race, even though gender and labor are mentioned (e.g., “Women–Employment”). Yet, just to right of those records, the social tag “african american” is provided by a Flickr member.

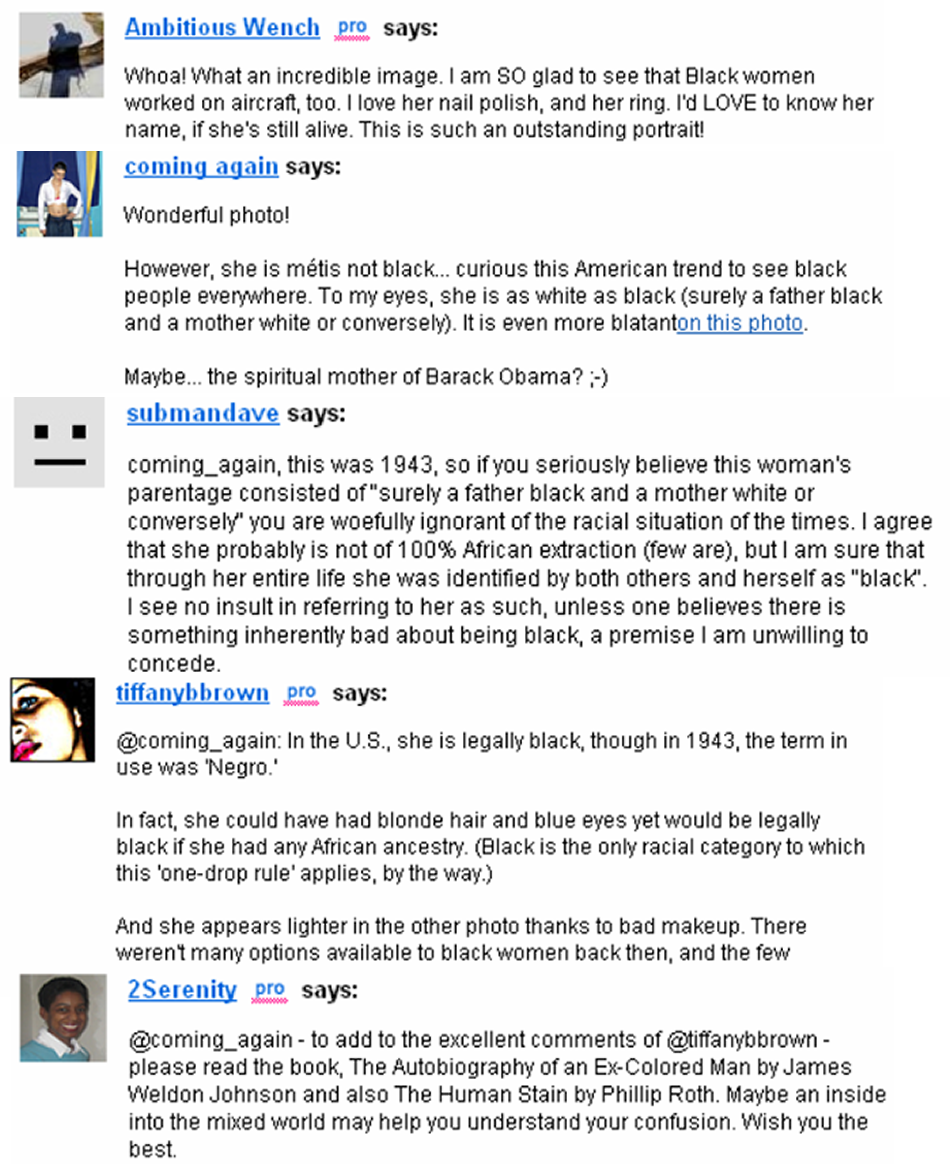

While not pictured in the image above, “black” and “american” also appear below “african american” in the list of tags. Interestingly, “black” immediately precedes “american” in the list, suggesting that one user may have purposefully entered them both in a contiguous, but not necessarily connected, way. Still more interestingly, the comments beneath the image are rife with conversation about race. These comments are conversational in character and include claims such as the following (listed in descending chronological order):

These examples indicate that, as comments aggregate over time, a debate about metadata and its role in archiving and locating the Rosie image emerges. At the center of the debate is how to position the person who is pictured and—more broadly—how to better understand the historical status of race in classification systems. In comments on the image, people discuss the juridical, cultural, and embodied character of “black,” “Negro,” “African,” and “métis.” Of these options, “métis” and “Negro” are not listed as tags on the Flickr page, perhaps for a variety of reasons, including the fact that tags are limited to 75 in number. Another reason is that popular rhetorics of colorblindness and happy multiculturalism discursively lend themselves to avoiding terms such as “Negro.” But regardless of the explanation, the point here is that metadata, in isolation, can be too easily reduced to the “merely descriptive,” with tags like “black” or “african american” becoming apparently logical effects of plain observations and routine categorization. In the Rosie instance, what’s particularly telling is that no questionnaire or form is necessary for people to begin tagging images through a template’s logic. That logic is naturalized.

Put pithily, then: when articulated with culture, history, and other components of a Flickr page, those 85% of the tags in the LoC’s Flickr collections become subject to questions of what everyday and technical—what implicit and explicit—standards are fostering the co-production of metadata in the first place. With this inquiry in mind, the fourth most common tagging category in the LoC’s Flickr collections is “personal knowledge / research, ” including “tags that could only have been added based on knowledge or research by the tagger, and that could not have been gleaned solely from the description provided or examination of the photo” (Doctorow, 2001). According to the report, these knowledge / research tags represent 4% of the tags and—by their very definition and name—are distinct from “commentary” tags, gesture toward a single member’s expertise, and mine the knowledge work of Flickr’s member base (Doctorow, 2001). When compared with the three most common categories of tags, this fourth category would ostensibly provide more beneficial information to the LoC and others. More specifically, these tags might add historical details about a given photograph to the LoC’s records, or they might give users more context for an image, helping them situate it in a certain narrative or cultural moment.

In the Rosie instance, one example might be the tag, “A-31.” This tag references the model of the Vengeance bomber, made by Vultee Aircraft, that is in the Rosie image. As of this writing, no other reference to “A-31″ or to the model of the Vengeance has been made on the Flickr page for the Rosie image. Though minor, this tag builds upon expertise in the history of the airplane industry to add particularity to the LoC’s records and give Flickr users a means to find other images of this particular bomber model. Perhaps more interestingly, this tag has circulated with the image to other domains. On Wikipedia, the Rosie image can now also be found under the entry, “A-31 Vengeance” (2010). There, the image is described as follows: “A real-life ‘Rosie the Riveter’ operating a hand drill at Vultee-Nashville, Tennessee, working on an A-31 Vengeance dive bomber” (2010). As opposed to the LoC’s record on Flickr (e.g., “Operating a hand drill at Vultee-Nashville, woman is working on a ‘Vengeance’ dive bomber, Tennessee”), this Wikipedia description mobilizes personal knowledge / research (e.g., “A-31″) and commentary (e.g., “real-life”) to further qualify the image (erroneously or not).

However, one issue with the report’s categorization system is that, in its definition of “personal knowledge / research tags,” it tends to cleanly distinguish between individual knowledge and the mere description of an image. When looking at how race functions in the Rosie instance, this distinction is tricky at best. The informational ecology of the LoC’s records, the user comments, and the social tags on the image’s Flickr page are rife with ambivalence. Even if the plane is, in fact, an A-31 Vengeance bomber, the Rosie instance is simultaneously tagged as “black,” “african american” and “american.” It is through the explanation of how, by whom, for whom, and to what effects the image is “merely described” where knowledge production and research occur.

Such an explanation might be called a standard in the making.

[1] That data is parsed into two tables, which demarcate the Flickr images into their two LoC source collections: the Farm Security Administration / Office of War Information Photograph Collection (FSA / OWI) and the George Grantham Bain Collection.↑

[2] Miscellaneous tags are not easily understood or offer no correlation to the LoC’s records or to other descriptions provided by taggers. (Springer et al., 2008, pp. 18-19).↑