Decentralizing Folksonomies and Making Standards

As it is currently understood in the GIScience literature, metadata is not equivalent to folksonomic tagging systems. Traditionally, metadata is an “agreed-upon” standard of documentation. I understand it as a distributed practice with a centralized protocol. Metadata documentation standards are developed such that individuals and organizations can record contextual information thereby situating the ways in which the data were produced and outlining the appropriate ways in which the data should be enrolled. These standards are centralized such that a diversity of individual and organizational bodies can access the data situationally. “Folksonomies”—systems of collaborative classification and tagging—are typically understood as not centralized. But in what specific ways are folksonomies decentralized? Can they potentially represent what we mean by “Standards in the Making” (SITM)?

Folksonomies are typically understood as flat, categorical spaces, in certain opposition to taxonomies (Mathes, 2004). Their use in the form of collaborative tagging demonstrates this “flat space” as one wherein multiple users mark a particular object with labels thereby allowing for searching or clustering of web-based artifacts. Tags are not placed in hierarchical relationships to one another. As a result, an artifact could potentially have an infinite number of tags which characterize/categorize the object, although Golder and Huberman argue that tagging behavior, over time, demonstrates a certain amount of imitation (Golder & Huberman, 2006). The possibility of intersecting folksonomies with traditional GIS technology has been most prominently advocated by Renée Sieber in her research on GIS use by “grassroots” groups (Sieber, 2004; Sieber, 2007; Harris & Weiner, 1998). Here, Sieber imagines a “multi-vocal and contradictory GIS/2” where, “applications may be delightfully chaotic, or at least unnerving to the traditional GIS developer” (2004, p. 37). In this GIS/2, outfitted with XML, users would annotate their conflictual narratives into the spatial representations using a tagging system. This GIS, Sieber continues, enables a technological space where “problem definition and interoperability and reconciliation (if at all) as well as legitimacy and valuation become a matter of debate instead of optimization” (2004, p. 37). In conceptualizing the production of spatial representations as compositions, how might folksonomies contribute to an awareness of the multiple affordances and constraints in making media? Do folksonomies, or distributed annotations of a “text,” enable SITM?

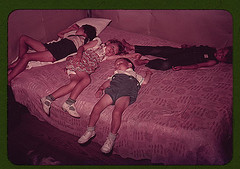

In thinking through this question, our group explored The Commons, a Library of Congress sponsored photograph collection housed at Flickr.com. One particular photo displayed a number of ‘annotations’, having been viewed nearly 10,000 times. The photo, titled “Children asleep on bed during square dance, McIntosh County, Okla.,” is found within the 1930s-40s Color collection. Four children are collapsed in various poses on a bed. Three appear to be sleeping, while another one stares out, away from the camera. Nearly thirty tags collectively organize the photo, including “sleeping,” “napping,” “eerie,” “bed,” “pillow,” “flaked out,” “vintage bedspread,” “jumper,” “barefoot,” and “surreal.” On the photo itself, five users marked out spaces for their notes. Over a young boy’s head, the user valhall64 noted, “I love this pic…” Another user, Maanskyn, potentially annoyed by this annotation, composed a note directly on top of the previous user’s note: “That is not useful metadata.” Another user, sgbradley, marked the shoes of the little boy and girl, “Shoes & socks need to come off.” Below the photo, users commented on their enjoyment of the photograph. Admins of other Flickr groups requested that the photo be allowed into their groups: the “Soulful Group,” “Piece of Heaven,” and the group titled “The Natural Beauty of Children.” Two users tag the photo by the photographer’s name, “Lee, Russell” and “Russell Lee.” Another user comments on the photo and includes the link to Russell Lee’s Wikipedia entry.

These annotations provide handles for future users to locate the photograph. They make the photo a searchable text. These annotations are not centralized in the sense of a taxonomy. They emerge from multiple readings of the photograph. They are not agreed upon, per se, nor are they necessarily a shared vocabulary. They are potentially disruptive or extensive of the photograph, in much the same way that GIS/2 can be disorienting for the traditional GIScientist. And yet, the collection of these annotations is hardly decentralized. They exist to motivate a “common understanding.” The tags, notes, and comments all exist in the schema of Flickr—designed to reside within their servers, to make more efficient the processing of the photo for future readings. These annotations are, in this sense, standardized forms of documentation. They have been systematicized. In this sense, these annotations function as metadata, traditionally understood—centralized and distributed. The photo, “Children asleep…,” is documented through distributed inquiry into how it should be tagged, while maintaining a centralized understanding of how those tags, notes, and comments should be appropriately composed. Indeed, Sieber recognizes this in terms of her imagined GIS/2, where agreement upon the set of user-generated tag, towards a “shared vocabulary” is ripe for problematization (2004, p. 36).

Perhaps, the coding of these annotations in the LoC Flickr Commons has become too crystallized, too stabilized, too group-think. This instantiation of a folksonomy is too centralized—the possibility for annotations have been pre-figured into bins for tags, notes, and comments. This systematization allows those controlling content to speedily remove or subvert the intent of any reading. Beyond making a mess of this system, ”Standards in the Making” implies a different documentation practice: to extract the link to the photo such that it can be placed in a new context, to mark up the object by tearing it from its source-code home, to demonstrate a multiplicity of individualized and made standards, to make media by producing standards without confronting the horizon of the Standard.