Conclusion

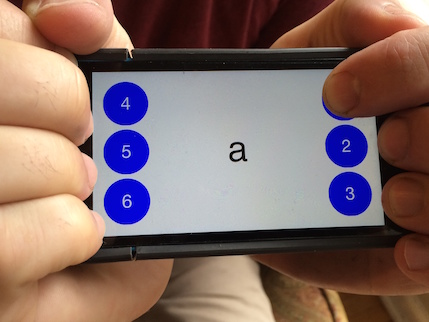

As a parting example of how a disability perspective might serve as a catalyst for newer and more universal designs consider the BrailleTouch app (Frey, Southern & Romero, 2011), an eyes-free texting tool developed by researchers at Georgia Tech. BrailleTouch utilizes the six dot braille grid as the mode of input; “users hold BrailleTouch with two hands, and use their fingers in a layout and functionality with a one-to-one correspondence to a Braille writer” (p. 5).

The app, which is currently available, was developed as a simpler and more cost-effective alternative to braillewriter technology. Even though the BrailleTouch was created with blind and low vision users in mind, media reporting about it has focused on its uses as improvement on the visually-based QWERTY keyboard. Georgia Tech’s press release about BrailleTouch begins, “Imagine if smartphone and tablet users could text a note under the table during a meeting without anyone being the wiser. Mobile gadget users might also be enabled to text while walking, watching TV or socializing without taking their eyes off what they’re doing” (Georgia Tech, 2012). The Los Angeles Times declared, “The app is designed for people who are visually impaired, but that doesn't mean the rest of us can't use it too” (Netburn 2012).

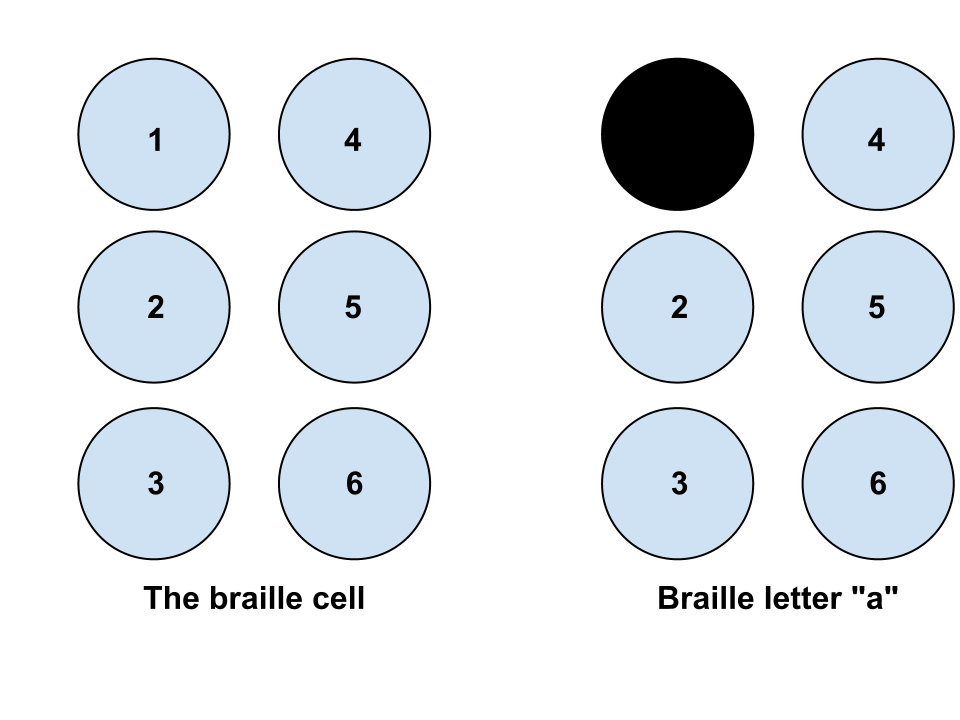

Applications like the BrailleTouch provide an entrance into a practical discussion about representational technologies and the possibilities for more fully multimodal literacy practices. It is easy to get caught up in the prescriptive aspects of literacy (spelling, punctuation, the alphabet itself), and to forget the basics of what literacy does: convey information, “reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a message selected at another point” (Claude Shannon, quoted in Gleick). The perceived value of the BrailleTouch app for all individuals, regardless of prior braille knowledge or level of vision, rests on braille’s status as “the first effective digitization of writing” (Daniels, 1996, p. 86). Rather than selecting from the 26 letters of the QWERTY keyboard, the user selects a series of chords from the combination of six braille cells. For each letter, the user makes an on/off choice for each cell. For instance, the letter “a” in braille is determined by cell 1 being “on” and the remaining five cells “off.”

Another possibility for digital/ alternative alphabet as text input was proposed with Gmail Tap: a Morse code texting tool and the subject of Google’s 2012 April Fool’s product announcement. Gmail Tap uses the dot, dash, and space of Morse Code to simplify texting and to facilitate eyes-free use. The product specs include the forthcoming feature, “Double-black diamond mode” which, through the simplicity of using a code of only thee keys, allows the user to write eight messages at once. The product specs also embrace multimodality by making a note to “engage all your senses” through “optional audio feedback.” While Gmail Tap was part of the yearly April Fool’s joke, users can download a Morse Keyboard at Google Play, and Google Research is actively exploring eyes-free computing applications. Gmail Tap seems both preposterous and plausible, offering a glimpse into the realms of possibility for literate practice and demonstrating the “cultural anxiety about literacy” (Trimbur, p. 291) that arises from multiplying literacies.

While texting is only a minor aspect of literacy practices, these two examples provide an opportunity to question how we access reading and writing, the options available to us, and the aims and purposes of literacy practices. These multiple remediations of digital print reveal what literacy can be and remind us that our reliance on strictly alphabetic print is habitual, but not absolute. The NFB, as explored at the beginning of this chapter, has been instrumental in developing new audio-based literacy technologies. They are not averse to textual innovations, but they are committed to the reification of print as literacy and relegating all other modes to supplemental status. Sound, for instance, can support literacy but it cannot be literacy. In terms of the examples discussed here, BrailleTouch and Gmail Tap, the braille app would be considered under the umbrella of literacy, but the Morse code app would not.

Writing dominates, but it is not our only mode of representation and communication. Trimbur (1991) asks us to "see literacy crises conjuncturally, as strategic pretexts for educational and cultural change that renegotiate the terms of cultural hegemony, the relations between classes and groups, and the meaning and use of literacy" (p. 281). The history of blindness and literacy, and the contemporary crisis discourse represented by the NFB, offers one such conjuncture, the combined considerations of technology, modality, and the body. The discourse of crisis surrounding blindness and literacy narrowly emphasizes braille as a "unitary standardized abstraction" (Trimbur, p. 292), and misses an opportunity to explore the “variable concrete practices” (p. 292) of literacy that blind individuals use. Behind the crisis discourse offered by the National Federation of the Blind, there is a rich story of adaptation and innovation, an unexpected glance of literacy’s possibility.