A Brief History of the Braille Code

Our definition of a literate society inevitably shifts as our tools for reading and writing evolve, but the brief history of literacy for blind people makes the prospect of change particularly fraught.

—Aviv, “Listening to Braille,” 2009

Writing is a technology, a code, just one mode of literacy yet its long history dissuades us from understanding its status as such. As Gleick (2011) notes, “It takes a few thousand years for this mapping of language onto a system of signs to become second nature and then there is no return to naiveté. Forgotten is the time when our very awareness of words came from seeing them” (n.p., emphasis added). Writing made language visible, yet its visual nature is its limitation; language made visible means little to someone who cannot see it. The braille code, language made tactile, was invented to address this limitation in the technology of writing; because the history of the braille code is much shorter than that of writing, it allows us insight into the development of development of a literacy technology.

Braille was developed to be a direct matching of the alphabet, a one-to-one transcription. The basic system of tactile dots was derived from a night writing code developed by Charles Barbier, an artillery captain in the French army; the initial aim of Barbier’s system was to facilitate communication by touch (and in the dark) for military maneuvers, but Barbier also assumed that the system would be valuable to the blind. Barbier’s system consisted of a 2x6 matrix of 12 dots, with each arrangement of dots mapping to a sound 4 in the French language. Barbier introduced his system of writing to the Institut National des Juenes Aveugle (Royal Institution for Blind Children) where Louis Braille was a student. Braille saw the value in Barbier’s code, but worked to improve it by cutting back on the number of dots to a 2 x 3 matrix of six, reducing the size of each individual dot, and linking the various dot arrays to letters of the alphabet rather than sounds.

War of the Dots

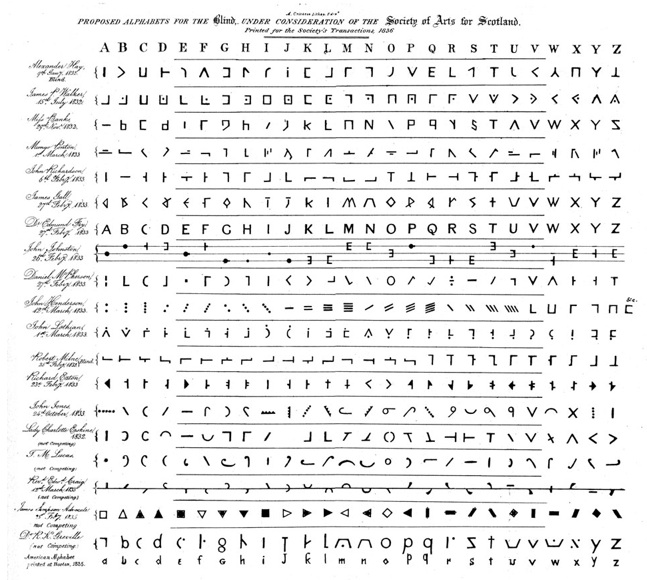

While Louis Braille developed his code in 1829, it did not become standard usage in the United States until 1932. Before its uniform adoption, there were a variety of tactile codes in active use in the U.S. The multiplicity of codes led to inconsistent access to print materials, and inconvenience and cost for readers. Because of the challenges presented by the inconsistent use of multiple tactile codes, a long-term effort was made by various blindness-related schools, publishers, and organizations to agree on a uniform code. This long debate was dubbed “the war of the dots,” a conflict that “was acrimonious in the extreme. The bitterness can hardly be imagined” (Irwin, 1952):

The American blind were tired. . . of changes. Many still living had first learned linetype, then New York Point, then American braille, then Revised braille grade 1 1/2. The rank and file of finger readers had a good deal of sympathy with a speaker at one of the national conventions who in a burst of oratory said, ‘If anyone invents a new system of printing for the blind, shoot him on the spot."

The “war of the dots” concluded with the adoption of Grade 2/ contracted braille (also known as “literary braille”) as the standard code for printing and education for the blind. The adoption of Grade 2 braille as the standard was based in part on perceptions of reading efficiency and ease, but also on perceptions of mapping to existing printed/ alphabetic text. New York Point, for instance, was critiqued because it did not employ capitalization or punctuation as would typically be found in printed English. Grade 2 braille is based on the alphabet, but it does not retain the one-to-one coding of Braille’s original code; in contracted braille, for instance, the word “braille” would be presented as “brl.” The adaptations and condensed word forms of contracted braille link it to one of the bugaboos of contemporary literacy debates: texting.5 That fully-literate braille practice is quite similar to the frequently-perceived illiteracy of texting demonstrates the highly contextual and variable nature of literacy.

What is interesting about the war of the dots is not only the divisive nature of the debate, but that there was a debate at all—a systematic assessment of the efficacy of various coding systems, leading to a shared (though not universally popular) decision. The war of the dots reveals that there are always multiple possibilities for representation available to us. The history of writing is long, so it is difficult to capture these moments of decision, to articulate the arbitrariness of language and literacy. Braille’s condensed history and its current literacy crisis provide a window into how arbitrary choices of representation become absolutisms of literacy. Through braille’s history we can see the alphabet more fully as a technology and observe other possibilities for representation available to us.

Notes

4Barbier called his invention “sonography.”

5The debate surrounding texting and literacy is nicely summarized in linguist David Crystal’s Txting: The Gr8 Db8.