Instructor Perceptions of a Flexible Writing Classroom

Dana Gierdowski, Elon University

Introduction

Designing

Methods

Results

Tool for Engagement

Interaction with Peers

Engaging with Course Content

Obstacles to Teaching

Mobility

Visibility

Findings from the data collected from classroom observations and interviews with the instructor and teaching assistant relate to questions of perception. The data suggest that the instructors perceived the space as having both positive and negative qualities that affected themselves and their students.

The results collected for this study suggest that both the instructor and the TA developed a strong perception of the flexible classroom as a useful tool for engaging students through cooperative learning activities. As it relates to this study, the space as a tool for engagement is defined by the perception that the classroom and its associated resources (such as the movable furniture, LCD screens, and whiteboards) are tools that can be used to encourage students to participate in class activities, interact with their peers, interact with the instructor, and hold their attention.

During his interviews throughout the semester, the instructor commented on how the resources in the room were devices that were helpful in encouraging students to engage with each other during class. When asked about his thoughts on the classroom’s effect on peer workshops, the instructor reported that the new layout was a marked improvement over the fixed tables (such as the pod configurations that existed in the classroom during the pilot laptop study and several weeks into the semester of this study). He described the room before its redesign as “locked into four stations,” which was difficult to work with when he assigned cooperative learning lessons:

Instructor: [B]ut four stations of five to six students is just terrible, you know this.

Interviewer: In what way?

Instructor: Because working in groups of two or three—[students] are just always setting up in an awkward way. I use to have groups of three who would sit in a row where the people on two ends don’t see each other. They won’t move unless I tell them to move, and that’s not always the best way to make that happen. But the smaller furniture—I mean, they’ll all take one of those square tables and they’ll sit around there … sometimes they’ll take one or two of the little triangular-ish ones and one of the other rolling chairs and just make a little group, or even pairs. Sometimes they’ll take one of the rolling [tablet arm] chairs and just move wherever the other person is, and they’ll be able to face each other. (Audio file.)

On the first day that students had class in the space with the new mobile furnishings, the instructor gave the class an open invitation (and reminded them throughout the semester) to arrange the furniture however they preferred and in whatever configurations made them the most comfortable. Interestingly, I did not observe any instances throughout my observations where he specifically directed the students to move the furniture, and students did not move the furniture into configurations that significantly unsettled the seating patterns they had established with their peers early in the semester.

Despite this lack of direction from the instructor and lack of movement on the part of students, the instructor perceived the mobile furniture as a tool that helped students connect with each other in more meaningful ways during collaborative activities. The instructor specifically noted that the fixed pod configuration did not easily allow students to make eye contact and talk to each other; however, he also noted that the new furnishings facilitated contact among students working in groups, which created a more inclusive environment with no one being the “odd man out.” The previous design of the room, with four fixed stations seating six students each, was not conducive to group interaction; he observed that often one person, based on the seating design, would be on the periphery, isolated from the rest of the group. With the addition of the new furnishings, his comments demonstrate a clear perception that the ability to configure the furniture so that students can face each other promotes more interactivity and engagement between individuals within the group.

My classroom observations confirmed the instructor’s perceptions; that is, no instances were observed in which students grouped themselves in a linear configuration. When asked to form groups for peer workshops or other activities, students seemed to naturally arrange themselves in patterns where they could also see each other.

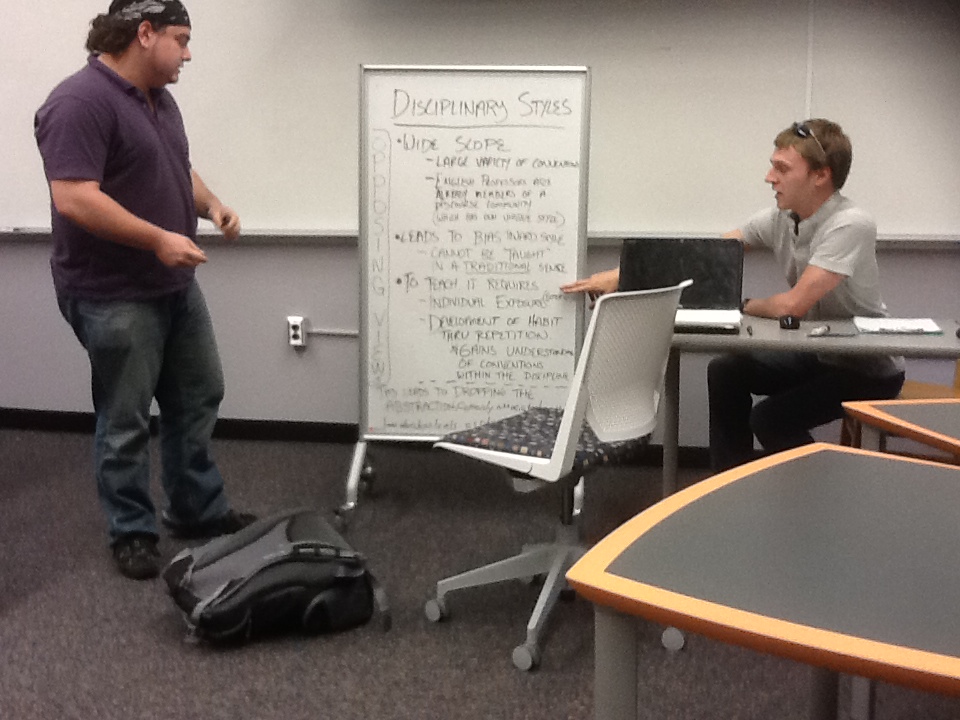

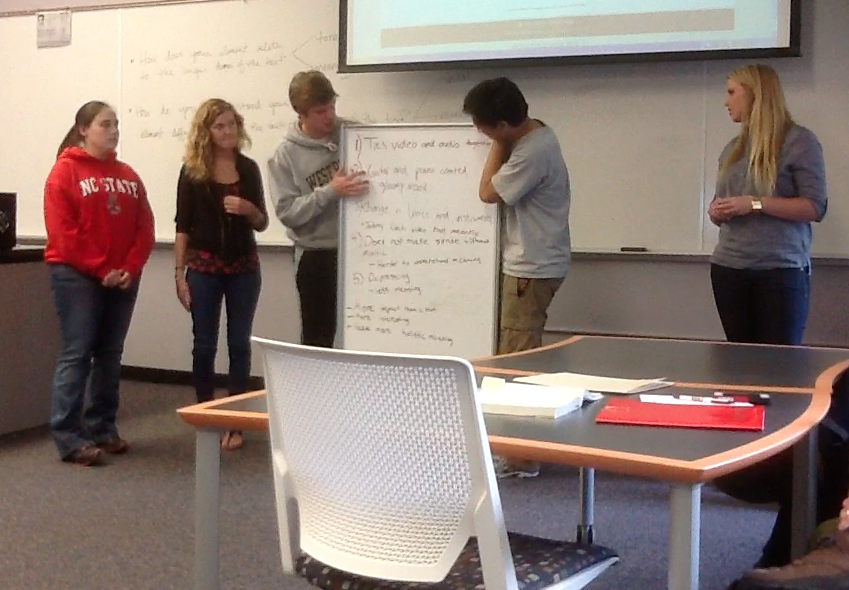

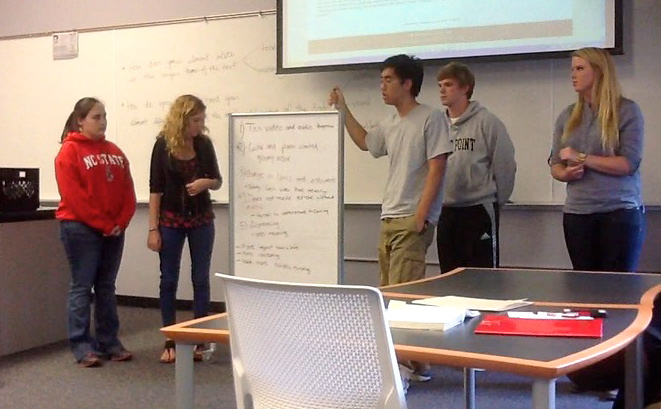

Figure 13: Students can now face each other

The instructor had a preference for the LCD screens when delivering course content to the class due to image quality and convenient sightlines; interestingly, he also perceived the quality and easy visibility of the LCD screens as tools for student engagement in the classroom. With five screens installed throughout the room, students had multiple sightlines to view displayed content. The instructor pointed out that students could configure the furniture in various ways and then gather around an LCD screen for an activity, which was a significant enhancement over the previous room design. He argued:

it’s hard for a bunch of students to cluster around a laptop. And even if they physically can do it, oftentimes they’re unwilling to do that. But if the room is more conducive to students gathering around at a central point and looking at what somebody is working on, it just works better. (Audio file)

He stated, “With the screens, there’s no reason for anybody not to be engaged.” The instructor also perceived that having students use the LCD screens to display their work during cooperative activities could be a positive influence on other groups working nearby:

The other thing is that students in groups can see what other groups are working on a little bit, and I think that’s great.

If there’s one group where nobody in the group really understood what the directions were, and theydon’t really know what’s going on, [then] they can kind of look around and catch up …They look next door and say, ‘Oh, now we see what’s going on.’

Figure 14: Students can learn by watching other groups to see what they are accomplishing.

The instructor saw the “semi-public” nature of the LCD screens as a tool that empowered students to problem solve as a group by looking to their classmates; as a result, engagement with each other and with the course material increased. Similarly, the instructor also perceived students as more engaged when watching videos and other multimedia projected on the LCD screens due to their convenient placement in the room:

I think [it was] their ability to kind of watch these sorts of things in a way that’s active—where they’re really paying attention—as opposed to just being on the front screen where it’s a little more blurry and a little bit further away, and they have to kind of crane their necks. And I think they’ll watch for a little while, and then before long half of them are disinterested and doing other things. (This video features the audio of this text with images of students watching the wall-mounted monitors.)

Students’ proximity to the display screens and the ease with which they were able to adjust to see a monitor was perceived as having an effect on their ability to engage with the course content.

In addition to the LCD screens, the mobile whiteboards were also considered an engagement tool for students, encouraging them to be more active and mobile in the classroom. Both instructor and TA expressed a strong preference for the mobile whiteboards, which was unexpected by the design team and the instructors alike. The whiteboards were thought of as more flexible than the LCD monitors, and this flexibility gave the instructors additional options when planning lessons. While the LCD screens were in fixed locations, the whiteboards had the luxury of movement in the space. The instructor stated:

If you have students working on short presentations that you want to have them deliver in class, you can have them roll them right to the front of the room and now they are sort of up on a stage, so they can work on them in their more secluded place, but they can then bring out what they’ve worked on. There are so many good things about those. [Students] can’t get buried in their laptops …the whiteboards sort of force them to just move a little bit away from the space where they’re comfortable, and they kind of come out and engage in their groups a little better. There’s so many things we can do with them that I wouldn’t have even thought would have mattered. (This video features the audio of this text with images of students working with white boards in the classroom.)

As evidenced here, different activities with various parts could be assigned using the mobile whiteboards. The instructors recognized the benefit of having the boards on casters, as they could be used for a variety of purposes even within one activity, including as an invention space, a revision space, a visual aid for in-class presentations, and even a partition screen for those wanting more privacy during their group work, all of which were noted during my observations. The instructor reported that, when using a whiteboard as a screen, students could have enough privacy to feel comfortable working in the space, but they were not so secluded that he could not check in with them to monitor their progress. He added, “it’s okay with me if they form their own little group with a little separation when they’re working, and sometimes they do better work that way.”

Standing up and moving about the classroom to use the boards was also perceived as an advantage. The instructor made particular note of the benefits of students using the whiteboards because their physical movement often required them to detach from their laptop computers and connect with other members of their group for collaboration. He noted that the computers, while valuable, could also encourage students to “retreat into their own little world too much”; however, when using the mobile whiteboards, he saw that students were encouraged to move away from their computers and engage more in the “community” of the classroom.

The instructor also believed that students were engaging more with the course material when using the mobile whiteboards. In several of the lessons the TA taught, groups were assigned whiteboard presentations, wherein each small group shared its whiteboard with the whole class at the end of an activity. The TA noted that, with a whiteboard presentation, students were asked to stand up and “assert their own authority in the classroom,” which encouraged deeper engagement with the content since students were accountable to their peers.

Students were usually given a choice of recording their work on a whiteboard or hooking up their computers to an LCD screen and typing their work for a given activity. Both instructor and TA recognized that the majority of the groups chose to use the whiteboards, and the instructor felt this format could be more productive for some students. He noted that they filled their whiteboards with information and generally wrote more on them than when they were asked to use their laptops with the large LCD screens.

|

|

|

Figure 15: Whiteboard individual presentation |

Figure 16: Whiteboard group presentation |

Figure 17: Whiteboard presentation |

The instructor commented in his first interview that one of his standard teaching practices has been to modify his lesson plan to incorporate collaborative work if students did not appear to be engaged in class discussions. I observed instances of this practice when the instructor posed a question to the class and got few or no responses. For example, early in the semester the instructor taught a lesson on the concept of “genre,” and he opened with the question, “What is genre?” When no one offered an answer, he asked the class to research “genre” on their laptops and then discuss what they learned with the others seated at their tables.3

The instructor, TA, and students who were interviewed in the second portion of the study characterized the class, collectively, as quiet and not particularly participatory. Students often demonstrated a hesitancy to share their thoughts in whole class discussions. However, when they were asked to work in small groups, the instructor believed students were highly productive and social. Due to their collective nature, the instructor stated that he used small group assignments and collaborative work frequently on a moment’s notice, in order to get students involved. In a later interview, the instructor commented that this kind of teaching “on the fly” was easier due to the flexible design of the space. He stated:

[The classroom] gives me the flexibility to change things up on a fly, which I do a lot… I don’t wait too long before I break them up in small groups or something like that and just kind of make it up on the fly … So, the furniture definitely lets me do that.

The instructor said that over the course of the semester he came to class each day with the expectation that he might need to alter his lesson if the students were not participating as a whole class. He noted that in other classrooms he would most likely take the same approach for students who were not actively participating, but he pointed out, “I know I can break the room up in different ways now, so that’s good.” In other words, the flexible design of the classroom made teaching “on the fly” easier. Interestingly, the data from the classroom observations in this study revealed that the instructor rarely changed (or asked the students to change) the classroom configuration; however, it appears that merely having the option of rearranging the space added to his positive perceptions of the classroom.

While the data suggested that the flexible classroom and its resources could be used as a device for engaging students more actively in their first-year composition course, a pattern was also identified that suggested the space could be perceived, at times, as an obstacle to teaching. For this study, an obstacle to teaching is defined as the instructor and TA’s perception of the space or its associated resources (such as furniture, whiteboards, and LCD screens) as a barrier to their teaching and general comfort, making navigation within the room and the execution of particular activities complicated or more difficult than in classrooms with different layouts or designs. These barriers varied by degree and were related to the instructor/TA’s perceived issues with visibility, positioning, and mobility within the classroom.

The instructor considered his ability to move freely about the classroom as an important part of his teaching practice. As such, when the instructor felt he could not easily navigate the classroom space to interact with students, he perceived the space as an obstacle to his teaching.

When asked about how he would characterize the ease with which he could navigate the classroom, he responded, “It depends how the furniture is set up.” All the instructors who taught in the flexible classroom during the first semester the room was used collectively decided there would be no default floor plan for the classroom when a class vacated the space, other than moving furnishings and whiteboards away from the classroom entrance and clearing the main path to the instructor lectern before the next class began. In other words, the furniture could be left where it was from one class to the next, with the understanding that each instructor and/or class (as some instructors expressed an interest in seeing how much agency their students would assert if they were given free license to move the furniture) would have a choice on how to arrange the room when they occupied it without being influenced by a default layout.

Since there was no established rule for where the furniture should live from class to class, the arrangement of the flexible classroom looked different for most of the classes I observed, and it never reflected the original floor plan the design team created. The instructor described the unpredictable layout of the space as having an “element of chaos” which could be difficult to deal with on a daily basis. For example, during one classroom observation, the previous class and instructor arranged the tables down the center of the space, akin to a boardroom where students faced each other across the tables. Keeping with the pattern that he had established at the start of the semester, the instructor began the class and did not ask students to move the furniture into another configuration.

After assigning a cooperative activity in which students were asked to review an assigned reading, he invited the class to move the furniture around the space for their group work. Several pairs of students moved tables away from the center to the periphery, and they stayed in these spots as they worked on two cooperative activities and then read a sample paper silently as a class; during their reading (about an hour into the class) the instructor stated to the TA, “I’m definitely going to move this furniture around for the next class. I don’t know where to stand.” With this statement, he demonstrated his discomfort with the current configuration, noting that he did not know where to position himself in the classroom to best facilitate the activity he assigned.

In his third interview, the instructor discussed his sense of confusion about how and where to move within the classroom. He reported that having several different types of furniture in the space that did not fit together cohesively contributed to his feeling of being crowded; and at times he perceived this crowding as a barrier to his teaching. Due to the mobility and size of some of the furnishings, particularly the self-contained tablet arm chairs, he remarked, “there are times when you’re kind of losing students in the corner [of the room] a little bit.” He added, “students can really scoot those into positions that make it hard to get the kind of interaction that I want sometimes.” My field observations align with the instructor’s perception in that the furniture seemed to “bunch up” towards the back of the room and near the classroom entrance at times; while there was usually plenty of space for tables, chairs, and the instructor’s lectern at the front of the classroom, few students chose to sit or work in this area of the room.

The instructor noted that placement of the larger tables in the room would sometimes create “little alleys and corners” that were difficult to find a way around when students were in their groups for a cooperative learning activity. He reported, “I can’t stand where I want to stand, so I can help them with something or listen in,” and he ended up in some situations where he was “tripping over them” as he moved from one group to the next. In these instances, he perceived the furniture placement as an obstacle to his ability to check in with students and monitor their progress. As noted earlier, I did not observe any instances in which the instructor directed or even requested students to move their tables and chairs from their typical seating patterns (which were established very early on in the semester) so that he might move with greater ease throughout the room. When asked about why he did not direct students to arrange the furniture in ways that he found more suitable, he responded:

Students can be a little possessive about the furniture they’re sitting in and how they’ve arranged it, and you’re almost kind of getting into their space a little bit. And sometimes it’s not worth pushing that issue. Sometimes they’re already engaged in an activity, and you see they’ve arranged things in such a way that’s not really conducive to what I want to happen in the classroom. Maybe because I can’t see what they’re doing or I can’t physically walk between groups or something like that. But asking them to stop and change and move things around is just too much trouble in the middle of a class. And I think that’s because there were just so many different types of furniture and configurations in that room. (This video features the audio of this text with images of students working in tight proximity.)

The instructor’s lack of direction can be attributed to both his pedagogical philosophy that allows students to exercise choice, as well as his respect for their personal space. His comments demonstrate an awareness of and sensitivity to his students’ comfort levels, based on how they chose to position themselves in the classroom, and an understanding of how asking them to move outside those comfort zones might affect their engagement and productivity within their groups.

While the mobile whiteboards were widely perceived as tools for engaging students, there were times during my observations that they appeared to be barriers to visibility in the classroom. During the same class when students sat in the boardroom configuration, they were asked to work in groups and record their responses to discussion questions on the mobile whiteboards. Most of the students moved only slightly from this boardroom set up (by pushing their chairs out from the tables and working to the side), if at all. When the instructor asked them to share their whiteboards with the entire class at the end of the activity, I observed that multiple sightlines—to both the teacher and the rest of the groups—around the room were obscured from various points based on where the whiteboards were situated.

When sharing their group work, students did not move the boards, and the instructor did not ask them to do so, even though he moved several times to the right and front of the room in an attempt to see each group as they reported their work. Later in the class, when students were reading independently for another activity, he moved some of the boards from the center of the space to the periphery. However, in a similar cooperative activity a few weeks later, the instructor asked the class, “Can I move a few of these boards out of the way so I can see everyone?” When they agreed, he rolled several of the boards out of his sightlines and to the sides of the classroom. His sensitivity to students’ comfort and personal space remains evident, as he posed his request in the form of a question versus a command or adjusting the boards on his own accord.

This observation data suggest an evolving level of comfort within the space on the part of the instructor; he became more comfortable with moving the whiteboards out of his sightlines (and often the sightlines of other students) after he learned that students did not seem to mind, and he did so with greater frequency. Data collected from the instructor’s second interview align with these observations, as the instructor noted that the whiteboards can “create problems sightline-wise, but I’d say they’re easily resolvable problems … all I need to do is reach over and pull it to the side a little bit and we’re talking as a class again. So, they’re ideal.”

The TA also noted this minor drawback to the boards to me during one classroom observation: “I can’t see the rest of the class when we’re using the boards. But it’s not really a problem—people will flag me down.”

While the instructor and TA noticed that the whiteboards could obscure their view of students working in small groups, both perceived these obstacles as negligible when contrasted with their versatility and usefulness. Similarly, despite the instructor’s unease with the disorganized nature of the flexible classroom during group work, he stated in his third interview that the “chaotic” nature of the space did not at all prevent him from teaching. He remarked that there were times when he wished that the space was more orderly, but that teaching in the flexible room overall was “definitely a positive experience.”

The teaching assistant also expressed that his experience in the flexible space was largely positive; however, he did suggest that the large lectern at the front of the room was an obstacle to creating a more student-centered environment. Characterized as a “walled fortress,” the TA stated that having a tablet computer or some other device to remotely control the instructor’s station (which included a computer, document camera, and the controls for all projection equipment, including the LCD screens) would have given him the opportunity to be out in the classroom and “on the same level as the students,” instead of being tied to the lectern when he needed to deliver content. He perceived the lectern as a barrier to the active, de-centered teaching he preferred to practice.