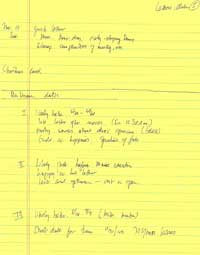

Not surprisingly, a good deal of purely textual effort preceded the multimodal work that would produce Mr. Secrets. This began simply, on a low-tech pad of yellow paper, as a kind of annotated list of what Millie’s letters contained. I read through, in chronological order, those letters with a definite date, saving for last seven letters that could not be dated with any certainty, and made short notes on each letter’s basic content.

And yet, as I look back on those notes now, I do encounter surprises. Even though I began this writing with the sole intention of tracking the letters’ chronology and contents, I find—having returned to that list—that I was already thinking of multimodal issues. As early as page one, I’ve begun making marginal notes (usually in square brackets) of ideas that would eventually find their way into the film’s voiceover script. Also as early as that page, I find that I was making speculative notes about which letters to draw from for audio reproduction within the film, and which letters to feature visually as part of the film. By the bottom of page two, I’ve also begun thinking of the possibility of zooming in on specific parts of a letter, so that the film’s viewers can actually read, in Millie’s handwriting, the words they are hearing through my collaborator’s female voice.

This kind of visual and audio anticipation has toned down by page four (except for the top-of-the-page note that will become part of the script), and is missing completely in the notes on the undated letters—which I was uncertain about using.

What emerges as I reconsider this earliest part of my work on the project is that I was mistaken in my opening phrasing here: when it comes to multimodal composing, it’s likely very rare that such a thing as “purely textual effort” occurs. When we set out knowing that our final goal is a multimodal piece, our awareness is already steering us toward thinking about the audio and visual components that it will involve.