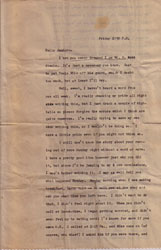

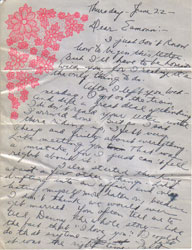

The single most important resource for the creation of Mr. Secrets was, in both content and visual reality, Millie’s letters to my father. Their tangibility—Millie’s handwriting; the varied papers, plain or decorated, on which her words were written; the envelopes and long out-of-print stamps; the letters’ aged scent—created for me, as I handled and read them, the human presence of their writer.

This power of theirs was brought home to me even more sharply when I began to type them up, so that parts of them could be voiced within the film, by my collaborative reader. In that typed form I found them inevitably “reduced”—both emotionally and morally—for me. (Interestingly, the same was not true for Millie’s one typed letter, perhaps because it remains a primary document, and is nestled within the collection, with all the other letters.)

And so, multimodality’s affordances became absolutely essential to my telling of the film’s story. The technologies that enabled me to show the actual letters as part of the film allowed me to retain and recreate that “human presence,” that sense of Millie as a full individual. Without the letters’ visual impact, I could see no way to tell the story as I wanted to—sympathetically, honestly, vividly. And once I started working with the technology that allowed me to present full letter pages, I discovered its further affordances—most importantly, the ability to zoom in on portions of individual letters, either as parallel to the part of them being spoken, or to make more visible particular words or features.

In the end, these letters—as the visual and textual basis of Mr. Secrets—were my most important prompt toward DMAC participation and multimodal learning, and the bridge to my own discoveries about the visual and audio technologies that would allow the film to exist.