Findings

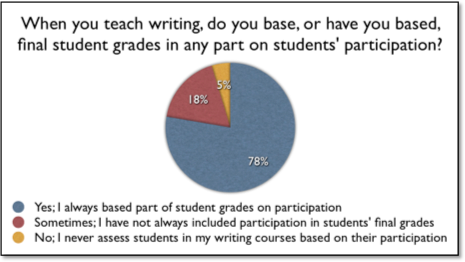

Figure 8 shows responses to the question of whether instructors base part of students' grades on participation. As Figure 8 demonstrates, of the 148 respondents to the survey, seven never base a portion of students' final grades on participation. The other 141, or 95%, do sometimes or always base a portion of students' final grades on participation. The result that nearly all instructors at least sometimes grade participation, drawn from instructors reporting from thirty-three different states, shows that the assessment of participation is a widespread practice in writing courses. Because participation does appear to be a widespread practice, the role of participation in writing courses is worth studying under the auspices of a common practice not often formally studied. In other words, if participation were still an uncommon assessment practice, as it was in the mid-twentieth century, a study of participation would look quite different. Because it is a prevalent practice to ask students to participate and then to grade that participation, this study must necessarily be oriented more heavily toward participation as an assessable item.

Instructors' Definitions of Participation

Teachers' definitions of participation reveal some common elements, including oral contributions in class and written contributions during or outside class. Other elements, including attendance, being prepared for class, listening during class, and professional behavior, are less common but still found across definitions. The survey asked respondents to define participation and provided a list of sample activities such as participation in oral classroom discussions, group activities, electronic discussion boards, or other sites where the assessment is based on participation in an activity. The large text box provided allowed participants to provide as much or as little detail as they wanted about how they defined participation. Some participants simply copied and pasted their syllabi statements into the textbox; others wrote 250 words or more about how they define participation.

Many articulations were thoughtful and reflective:

These vary per class because the students and the assignments make up the environment from which this participation must develop. There is always an element of each of these, but in varying degrees, depending on the needs of the students: conversation/conference for invention, evidence of revision…, portfolio. The syllabus says that attendance is taken by evidence of participation in the various classroom activities, so if they attend but do not participate, they might as well have not attended. They seem to respond to that, especially when I relate it to being on the job.

Other respondents pasted in statements and spent time explicating them:

Pasted from my syllabus: Participation (includes being prepared for class, taking part in class discussion every day, contributing actively to peer groups): 25% Participation in every class session is essential. Composition is not a class based on lectures and your active involvement in discussion and other daily activities is very important. Every day when you come to class you should have at least one observation, idea, question, point of discussion, or other offering available to generate discussion. As I indicated earlier, my definition of participation is much more broad than what I indicate here. I think I put the above blurb in writing so that when students question me at the end of the term about their grade, I have a firm policy to stand on. Some students think participation means showing up as a warm body to class, which simply isn't the case. I do think my written policy needs some attention and revision. I could make it more collaborative with students at the beginning of the semester, maybe a participation contract or something.

As these examples reveal, teachers' definitions of participation shed light on why teachers require participation: to help students get the most out of class by attending and being prepared for class; to create the types of classroom dynamics they value by expecting certain professional behaviors, oral contributions, and listening; and to compel students to complete informal writing activities. Instructors' definitions of participation provide a wealth of information about what they value, as the participation requirement is bent to fit their own assumptions and beliefs about what good writing classrooms look like.

Attendance

In the survey responses, attendance seems to be the precursor to other types of participation for those respondents who include it in their definitions; one respondent wrote: "attendance, group involvement and class discussion." If attendance is part of participation, it comes first, and then other examples are listed after it, such as "attendance, involvement in discussion and small groups, readiness, homework completed" and "attendance, attentiveness, completion of assigned work, engagement in small group projects" and "Usually, I define participation first through attendance. Then I look at whole class contributions." For a face-to-face class, attendance is obviously necessary for participation in the classroom, which makes it understandable that respondents would list it first. Of the respondents who included attendance in their definitions of participation, only two did not list it first.

Notably, attendance was not included as an example of a type of participation on this survey question, and I didn't ask any questions in the quantitative section of the survey about attendance as participation. A definition of participation that includes attendance is perhaps relying on the most basic of acts that could be considered participatory for a face-to-face class.

Preparation for Class

In addition to attendance, preparation for class is also a factor in teachers' participation grades and can also be seen as a precursor for actual participation. Eighteen respondents indicated that they consider "being prepared" or "preparing for class" as part of participation. Many of these responses make a gesture toward having completed reading specifically: a successful student "comes to class prepared to discuss readings"; "coming prepared to class with reading" is expected. Other responses specifically reference bringing materials to class: "having all materials for class (being prepared)"; "being prepared for class (brings appropriate materials, such as texts or laptops on the days we're using them)."

Oral Contributions for Class

The third key element in definitions of participation is oral contributions to class. Eighty-six out of 116 respondents mention oral contribution in some way. These responses include "small and large group discussions"; "class discussion"; "whole class discussion"; "office hours meetings"; "talking during discussion"; "they talk"; "speaking regularly"; and speaking up in class." Although these responses clearly fall within the boundaries of oral contribution, other responses were more ambiguous and difficult to code. For example, is "in-class engagement" an oral contribution? What about "contributions to groups or to full class"? I chose to code this category conservatively, only identifying those responses that directly referred to some sort of oral act.

A few respondents indicated oral contribution as the singular form of classroom participation: "In my composition courses, I have exclusively defined [participation] as oral contribution to class activities, whether those activities were full class discussions or small group work." Although many instructors used broader definitions, perhaps in part because of the difficulty assessing oral classroom participation, this definition is representative of a common construction of participation.

Listening

In addition to speaking, some respondents make clear that they count listening as well. When asked to define participation, twelve respondents indicated that listening or paying attention is part of their definition of participation. Furthermore, fourteen respondents who chose to copy and paste their syllabi statements about participation mentioned listening, so this is not just an articulation of expectations in the context of the survey—instructors are making it clear to students that they value listening as well as speaking. Instructors also sometimes noted that including listening is an act was meant to include shy students or students with disabilities: "I ask students to tell me if they have any reasons for not participating in class discussion—being shy, disability, etc. I take this into consideration when assessing their participation."

Professional Behavior

Although many of the behaviors mentioned by instructors as included in participation could be considered professional, or as preparation for participation in activities after graduation, four instructors mentioned professional behavior directly. Each of the four respondents articulates a unique aspect of professionalism and its relationship to participation. One instructor explains that participation is "putting in clear effort to informal writing assignments" which includes, "professional presentation (typed, proofread, etc)." Another instructor states, "For me, participation is tied to the overall ethos/professionalism that a student exhibits throughout the semester via their behavior in class, quality of submitted work, etc. […] Perhaps rather than calling it participation, I might rephrase it to professional contributions instead." Of the two other respondents who include some mention of professionalism in their responses, one is a copied statement from the instructor's syllabus: "In terms of professionalism, you will be evaluated on your preparation for and participation in class discussion, as well as your contributions to group work." The other instructor connects professionalism to work with people outside of the classroom: "When there's a community/service-learning component, participation comes into play—students' professionalism with community members, their direction of class periods that involve community members, etc." Though few respondents mention it explicitly, professional behavior seems implicit in participation requirements in general.

Written Activities

The final common element in definitions of participation is written activities, both in and outside the classroom. Many respondents who note some type of written activity as part of participation mention discussion boards, which is perhaps because I provided it as part of the example on the survey for this question. Still, electronic media seem to provide an important venue for what instructors are calling participation—informal communications amongst students. Other instructors note blogs and class listservs as other venues for that sort of communication. A few respondents mentioned activities that appear to be common invention activities listed in any writing teacher's instruction book (e.g. The St. Martin's Guide to Teaching Writing). These include "brainstorming activities" and "free write times."

Syllabi Statements of Required Participation

While the definitions of participation respondents provided on the survey offer glimpses into teachers' reflective thinking about their own pedagogical practices of requiring and assessing participation in their writing classrooms, syllabi statements of participation demonstrate one way instructors explicitly communicate their expectations to students.8 Syllabi statements are the brief descriptions of participation expectations teachers often include on the class syllabi they distribute to students at the beginning of the term. Although many of the definitions of participation include elements also included in the syllabi statements, the syllabi statements reveal some additional insights. For one, the statements reveal or imply some tension between instructors' and the institutional or programmatic expectations for standards of class-participation assessment. Secondly, the statements reveal the different roles instructors construct for their students and themselves in the classroom, emphasizing that students have responsibilities, instructors have rights.

Negotiating Institutional and Programmatic Contexts

It is important to point out that the language respondents may be using on their syllabi could likely be boilerplate or slightly modified material from their departments or even left over from other institutions at which they have previously taught. Though the participation statements were analyzed as though the respondents who contributed them own them, the respondents may not make such a claim. Those respondents who specifically state the language is not their own are acknowledged as such.

Some respondents distanced themselves from the question or from their response to the question when asked to provide a syllabus statement. One example of this distancing is the following statement, which explains that the text provided isn't one the respondent wrote: "Most of this statement is boiler plate from the syllabus we were assigned as new TAs. If I were to write my own completely, it would likely be very different." By positioning themselves as separate from the statement used, the writer avoids taking responsibility for the statement and what it includes. It's unclear from the response whether the respondent is permitted to revise the statement, but they do indicate on a previous question that the institution at which the respondent teachers requires instructors to assign students participation grades.

Though this issue of boilerplate language may seem mundane or commonplace, it actually points toward another challenge when attempting to assess participation—and one that institutions as a whole (rather than just individual instructors or even entire academic departments) need to give focused consideration. Participation requirements are often institutionally influenced, creating a tension between the institutional expectation and teachers' sense of what would work best in their classrooms.

Instructors who are required, or feel pressured to require, specific types of participation seek to create distance between their statements and their teacherly personas in survey responses. It's possible they find themselves doing the same thing with their students, which, to some extent, defeats the purpose of having a unified statement across sections at a particular institution. Perhaps departments would be better served by collaborating with instructors to develop participation statements in which instructors could be invested, creating less tension between administration and instructors and helping instructors teach more effectively.9

Constructing Student and Instructor Actions

Nearly all statements of participation from syllabi, except those just listing a percentage of the grade, list actions students should take. Students are responsible for all six of the activities discussed above: attendance, being prepared for class, oral contributions in class, listening during class, professional behavior, and written contributions during or outside class. Fewer statements—twenty-three of those provided by survey participants—list actions students should not take: these can be labeled as unprofessional behaviors. Students are also responsible for not engaging in unprofessional behaviors, including using technology inappropriately, acting in ways that prevent their participation, and being "disruptive."

One instructor included this statement:

Obviously, your ability to participate will be impaired if you are sleeping in class, text messaging, emailing, or having discussions with your neighbors. You are expected to refrain from doing any of these things out of respect for the instructor and for fellow students who are trying to concentrate. If I observe you doing any of the above, I will ask you to leave class and you will be marked absent for the day.

"Sleeping in class" and "having discussions with your neighbors" are examples of unprofessional behaviors; "text messaging" and "emailing" are examples of inappropriate technology use. The instructor offers a justification ("respect for the instructor and for fellow students who are trying to concentrate") as well as consequences for taking any of these actions ("I will ask you to leave class and you will be marked absent for the day").

Of the twenty-three statements instructing students on what not to do, nine mention technology—usually cell phones but also pagers, headphones, laptops, iPods, and the more general "electronic devices." Other instructors name the actions students should not do with these technologies as well: texting, checking e-mail, surfing the web, or allowing a cell phone to make an audible ring during class.

Beyond technology use, the other unprofessional behaviors include sleeping or other acts that preclude participation such as arriving to class late or leaving early. Instructors include "being unprepared" and "talking to or over others" as well as the more generic "being disruptive" or "disrupting others." One instructor includes this statement: "Derogatory comments/language in your speech or writing will not be tolerated." Occasionally, instructors provide a justification for asking students to not perform certain actions: "as a courtesy to others" or because they will "disturb the classroom environment" or because they are disrespectful, as in the example I provide above. Instructors are more likely to include consequences, which often refer to losing a specific number of points within a specific instructor's system ("you will receive no points," "you will lose participation points," "you can lose points") but also include being asked to leave the classroom for the day or being counted as absent.

Instructor Actions

In addition to defining the roles and prescribed actions or prohibited actions of students, syllabi statements also describe instructors' actions. It seems beneficial to students for instructors to identify what they will be doing over the course of the term. Instructors generally identify fewer actions for themselves than they do for students; many instructors identify no actions (or grading as the only action). The most common instructor action mentioned in participation statements from syllabi is one that refers to the process of assessment. Although most of the syllabi statements do not explicitly say the instructor is the one doing the assessing, it seems likely that if it were anything but the case, the instructor would make clear what they expected students to do. These statements range from a simple percentage grade ("Participation Grade: 10%" and "Participation, including in-class writing: 20%") to statements that indicate how participation will be graded: "on a 'pass or fail' scale", on a check plus/check/check minus scale, and so forth. Other statements offer students the opportunity to find out about their current participation grade: "If you are ever curious about your participation grade, feel free to ask." Survey respondents indicated that they generally chose to assess participation; twelve respondents out of 148 indicated that their institutions required them to assess participation.

In addition to assessment, another key action instructors identify for themselves in participation statements is the observation of students and the determination of what constitutes appropriate behavior and what constitutes disruptive or unprofessional behavior. Instructors list actions that are not counted as participation and are therefore tied to punitive action: "If I observe you doing any of the above [disruptive activities], I will ask you to leave class and you will be marked absent for the day." The antiparticipation acts listed come with the penalty of leaving class as well as being marked absent. Another respondent's statement includes this note: "If you are texting, checking email, etc. during class, I will ask you to leave and you will be charged with an absence for the day (see below) and you will not be allowed to make up any in-class work you miss." Some instructors go so far as to indicate that they will model proper behavior: "I know that 8:00 AM is an early start time, but I will make it to class on time, and so I expect you to be on time as well."

Instructors place themselves in their roles within participation statements by indicating what they have done, what they will do, or what they expect: " I expect you to be respectful and encouraging to your fellow community of scholars"; "I will give you a choice of several questions to answer on Thursdays"; "I have designed the course to use the most of class time, so it will be to your benefit to attend"; " I expect you to turn your cell phones off during class. If your cell phone rings or I see you texting during class, you will lose participation points, and I may confiscate your phone or ask you to leave (in which case you would be counted absent for the day)"; "I am looking for you to be engaged and ready to answer a question." One direction statement deviates slightly from the others: "I promise you that I will do everything in my power to make our classroom a safe space for us to speak to one another fairly and reasonably." This statement presumes a teacher who observes, surveys, and disciplines, but in the name of a safe space and not a focused classroom, as is implied in the earlier statements.

A more minor action instructors outline for themselves in participation statements is that they will be available: "Should anything hinder your ability to participate, please speak with me and we will work together to resolve the situation" and "contact me ASAP in case of major issues or problems that arise in a peer group." These statements indicate that instructors are choosing to be available for certain types of student needs: in the first, the instructor is available if the student is having a difficult time meeting the expectations of the participation requirement; in the second, the instructor is available to mediate student/instructor conflicts.

Two other statements stand out as particular outliers. In the first, the instructor appears to indicate that a valid instructor action is to make mistakes or be vulnerable: "You will each find yourself struggling to be articulate in front of one another, and often you'll get it wrong. I will, too." In the second, the respondent's statement indicates that part of the instructor's role is to not dominate the classroom discourse: " If I did all the talking, we'd all be bored to death."

8. Teachers may also explain participation requirements orally in class and through informal or formal written communications outside the syllabus—announcements in course-management systems, assignment sheets, and so forth. The survey did not ask respondents to include these types of documents or to document oral communication of participation expectations. [return]

9. Chapter 3 of Critel's dissertation discusses a syllabus archive from Research I Institution (RIU). The syllabus archive demonstrated that the evolution of participation requirements can be influenced by a recursive relationship between administrative/institutional requirements or expectations and instructors' practice. This can be a circular relationship whereby the administration issues a rule, which instructors follow, but the administration can also survey instructors and develop policy based on instructors' practice. Because this practice can be seen fairly clearly in the archive at RIU, it is reasonable to expect that similar relationships may currently be happening at other institutions. [return]