Methods and Methodology: Conducting a National Survey of Teachers of Writing

Methods

My research project was determined exempt from the Institutional Review Board procedure by the Office of Responsible Research Practices at Ohio State University on February 24, 2011. The survey was distributed via snowballing technique with a population of convenience; the invitation to participate was distributed via email and Facebook, and respondents were invited to send along the invitation to other friends and colleagues who teach or have taught writing courses. Some respondents reposted the original message to their own Facebook pages and others sent the message to departmental listservs.

Answering survey questions was optional, but participants were required to consent to the terms of the study and acknowledge that participation was voluntary after reading the Consent Form and to acknowledge that they were currently teaching or in the past had taught college-level writing courses. Any potential participants who did not assent to both were taken to a thank-you page with the researcher's contact information. Therefore, all 148 responses discussed below met those two guidelines. Three potential respondents were disqualified by the second requirement. In addition, participants could click a Save button on each page and return to the survey later. Finally, page logic was employed to determine which pages participants saw based on answers they provided.3 The full survey can be viewed here.

Demographic Information of Survey Participants

During the open window of March 15, 2011 to May 1, 2011, 148 current and former writing teachers completed the survey from thirty-three states. About two-thirds of participants provided their contact information and indicated their willingness to be contacted for a follow-up interview. A few others submitted responses from outside the United States, but they are not included in the current analysis since this discussion is limited to higher education in the United States.4

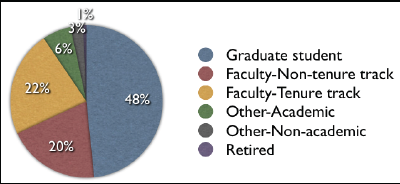

The survey began with background questions to get a sense of the population of respondents. Respondents were congregated more heavily in the eastern half of the United States, with particular concentrations in Ohio, Illinois, New York, Missouri, and Oklahoma (fig. 2). Forty-eight percent of respondents identified as graduate students, 22% as tenure-track faculty, 20% as non-tenure-track faculty, 6% as holding other academic positions, 3% as holding other non-academic positions, and 1% as retired (fig. 2). 5

Figure 3 shows the respondents by primary-identity category. Respondents could only choose one category, so if a participant was both a non-tenure-track faculty member and a graduate student, I asked that they choose a primary identification.

As Figure 4 shows, participants had the option of entering text into the "Other" box. I've provided their responses below, grouping like responses and listing how many times each one was entered.6

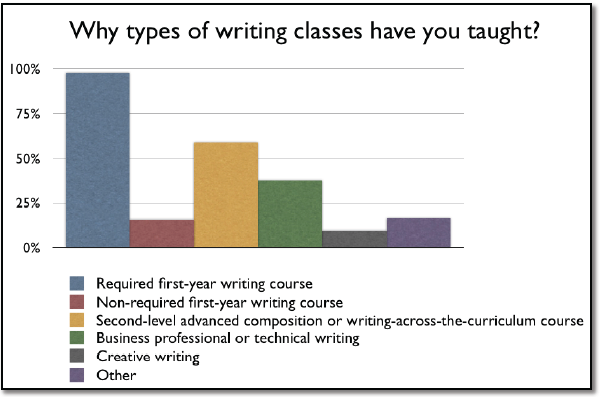

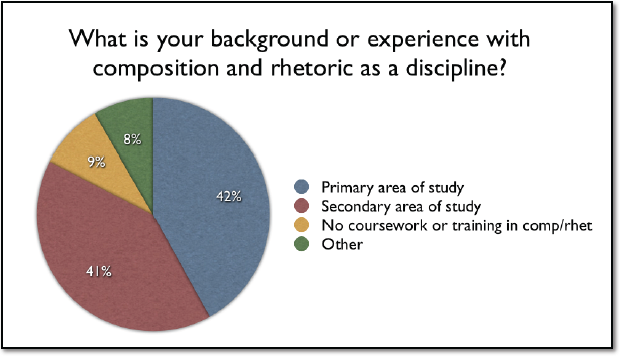

Nearly all respondents (98%) had taught a required first-year writing course, and more than half had taught a second-level or writing-across-the-curriculum course. Fewer respondents had taught business writing, technical writing, creative writing, or other types of writing courses (fig. 4). Forty-two percent of respondents identified composition and rhetoric as their primary area of study, 41% identified it as their secondary area of study, 9% indicated they had no coursework or training in rhetoric and composition, and 8% identified as "other" (fig. 5). Most respondents who selected the other category did have experience with composition and rhetoric but just used the "other" category to provide more detail about their experiences.7 Very few respondents had little or no contact with composition and rhetoric as a field of inquiry.

Only one respondent indicated no training (see fig. 5), saying, "Composition and Rhetoric is my main professional area, but I was not trained in it. (Too old!)." Although having a larger proportion of respondents with no background in comp/rhet would allow for data analyses demonstrating if those respondents had substantively different attitudes about participation, the absence of that population of writing teachers makes me hopeful that more writing teachers are getting some training or coursework in composition and rhetoric even if their degrees are in other areas.

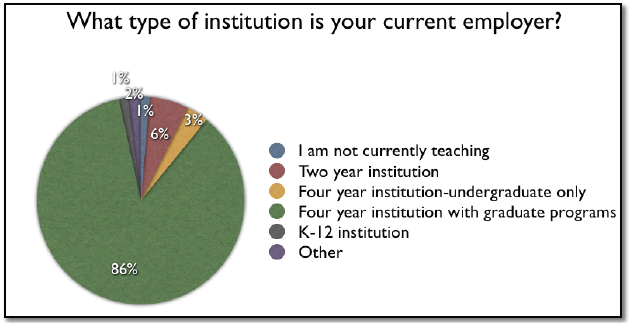

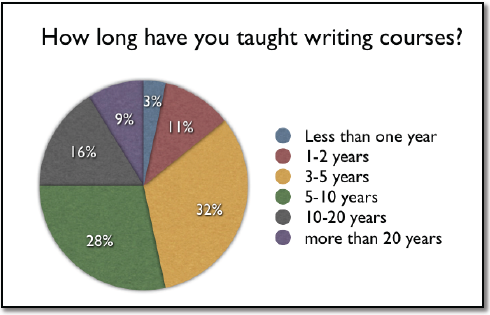

Eighty-six percent of respondents were teaching at four-year institutions with graduate programs, 6% at two-year institutions, 3% at four-year institutions without graduate programs, and 1% at K-12 institutions, and 1% indicated they were not currently teaching. Another 2% identified as "other" (fig. 6). Respondents marking "other" wrote: "Adult Education Program", "Catholic seminary with undergraduate and graduate students", and "I retired from a two-year college." Nine percent of respondents had been teaching for more than 20 years, 16% for between 10 and 20 years, 28% between 5 and 10 years, 32% between 3 and 5 years, 11% 1-2 years, and 3% less than one year (fig. 7). In total, 80% of respondents had 10 or fewer years of teaching experience.

Interestingly, some 86% of respondents taught at four-year institutions with graduate programs, a figure that lines up with the high percentage of graduate students who completed the survey. This information is certainly not representative of the population of teachers of writing courses in general. It would be helpful to gather more survey results particularly from respondents at two-year institutions. As is, that population is too small to use as a comparison.

Eighty percent of respondents had ten or fewer years of teaching experience, which again reflects the bias of respondents toward graduate students. As with the lack of respondents from two-year colleges, it would be interesting to gather more responses from writing instructors who have taught longer, and that data would allow for a better analysis of how experienced instructors might have different participation expectations than less experienced ones. In a follow-up interview, one respondent, who had just completed his fourth year as a faculty member at a research-intensive university in the Midwest, said his pedagogy had shifted away from the full-class discussions that dominated his teaching as a graduate student. It seems likely that most writing teachers pedagogies change over the course of their careers, particularly if they go from graduate student at a particular type of institution to a faculty member at a different type of institution.

Methodology

In this chapter, I am primarily focused on responses to two discursive questions in the survey. One question asked respondents, "How do you define participation?" The other question requested, "If you include a statement about participation on your syllabi, please copy and paste one or more statements of participation from recent syllabi if available."

Definitions of Participation

The survey asked respondents to define participation and provided a list of sample activities such as participation in oral classroom discussions, group activities, electronic discussion boards, or other sites where the assessment is based on participation in the activity. These definitions are important in that they provide a sense of instructors' reflective consideration of their pedagogical and assessment practices surrounding participation. The complete participation definitions were read through in their entirety four times and run through word-cloud and phrase-count generators, which provided assistance in developing a short list of key elements present across definitions. From the full set of definitions, the following list of codes was generated:

- Attendance

- Being prepared for class

- Professional behavior

- Oral contributions to class

- Listening

- Written contributions in or outside of class

Then, using an excel spreadsheet, the data was coded for each of the six codes with one pass through the entire data set per code. Although there are clear limitations to this method, it has brought to light some significant commonalities among the definitions respondents submitted. The method focuses on the content of the responses and not the construction of the responses, and demonstrates the most common elements across definitions. The six codes I identified in respondents' definitions of participation represent both the most common elements and the most significant deviations from the simple, traditional definition of participation as contribution to class discussion. Taken together, they shed light on why teachers require participation: to help students get the most out of class by attending and being prepared for class; to help create the types of classroom dynamics teachers value by expecting certain professional behaviors; to encourage speaking and listening in the classroom; and to compel students to complete informal writing activities. Instructors' definitions of participation provide a wealth of information about what they value, as the participation requirement is inevitably shaped to fit their own assumptions and beliefs.

Syllabi Statements of Participation

Syllabi statements are the brief descriptions of participation expectations included on syllabi distributed to students at the beginning of the term; these statements sometimes overlap with the teachers' definitions, but there is additional and sometimes quite different information revealed through these syllabi statements.

My analysis of the function of participation as it appears on instructors' syllabi centers on the role of participation as the explicit communication of teachers' expectations to students (rather than reflective thinking of instructors, not always made public or transparent to students) and on the power dynamics undergirding this communicative situation. I focus specifically on the following questions raised by the survey data: How do the unstated and often unrealized power dynamics in the classroom affect participation? What normative value systems are implied in notions of participation as they currently manifest in writing classrooms? From the syllabi-statement data, the following additional themes emerged in my analysis: negotiations of institutional and programmatic contexts and constructions of student and instructor roles, including implicit expectations for student actions and instructor actions.

3. For example, participants who answered that they never require participation would not have been led to the question asking what weight they give participation in their classes. Participants who indicated they had never taught in a computer-mediated classroom would not see the question asking if they modified the participant requirement for that type of classroom. This type of page logic is employed to cut down on the number of responses that are irrelevant because the participant is answering speculatively while also keeping respondents engaged for the questions more relevant to them. [return]

4. However, it was exciting to see a few responses come in from Australia, Africa, and Europe; international uses of participation in the writing classroom would be a compelling direction in which to take this research. [return]

5. Since the contacts I have are primarily with graduate students, it's not surprising that the population is weighted more heavily toward graduate students. In addition, I've not been able to locate any data indicating the percentage of writing courses at the undergraduate level taught by graduate students. This percentage of the population may or may not be representative. In any case, I would need to collect a much larger number of responses to make any claims about representativeness of the sample to the population as a whole. I do not aim to generalize about participation in all writing courses. [return]

6. Other responses included: multimedia, digital or multimodal composition (6); basic writing or developmental writing (3); ESL courses (3); lit survey course (3); film writing (1); graduate-level composition (1); second level writing-in-the-disciplines course (1); teacher training (1); writing center theory (1); autobiographical writing (1); disability and rhetoric (1); journalism (1); news writing (1); science writing (1); and a second-year writing course on rhetoric and spirituality (1). Late in the survey, respondents were asked to explain if there are changes in the type, quantity, or quality of participation depending on the types of writing classes they teach. Sixty-two responded by indicating there are changes, while twenty-eight responded that there are not changes. Eight participants responded with neither yes nor no; some of these had only taught one type of course, and others said they weren't sure. [return]

7. These included such responses as: "I have a degree in composition and rhet (MA) and a PhD in Engineering Ed"; "I have eight graduate hours in C and R"; "I have had one course in Composition Pedagogy"; "I took one course on the history of rhetoric"; "Now my primary field of study, have job in field, but degree is in another field'; TESOL Certificate." [return]