Art as Dissent

In other words, there are certain cultural values that extend across the decades; how they are hailed or interpellated depends on the values of the time.

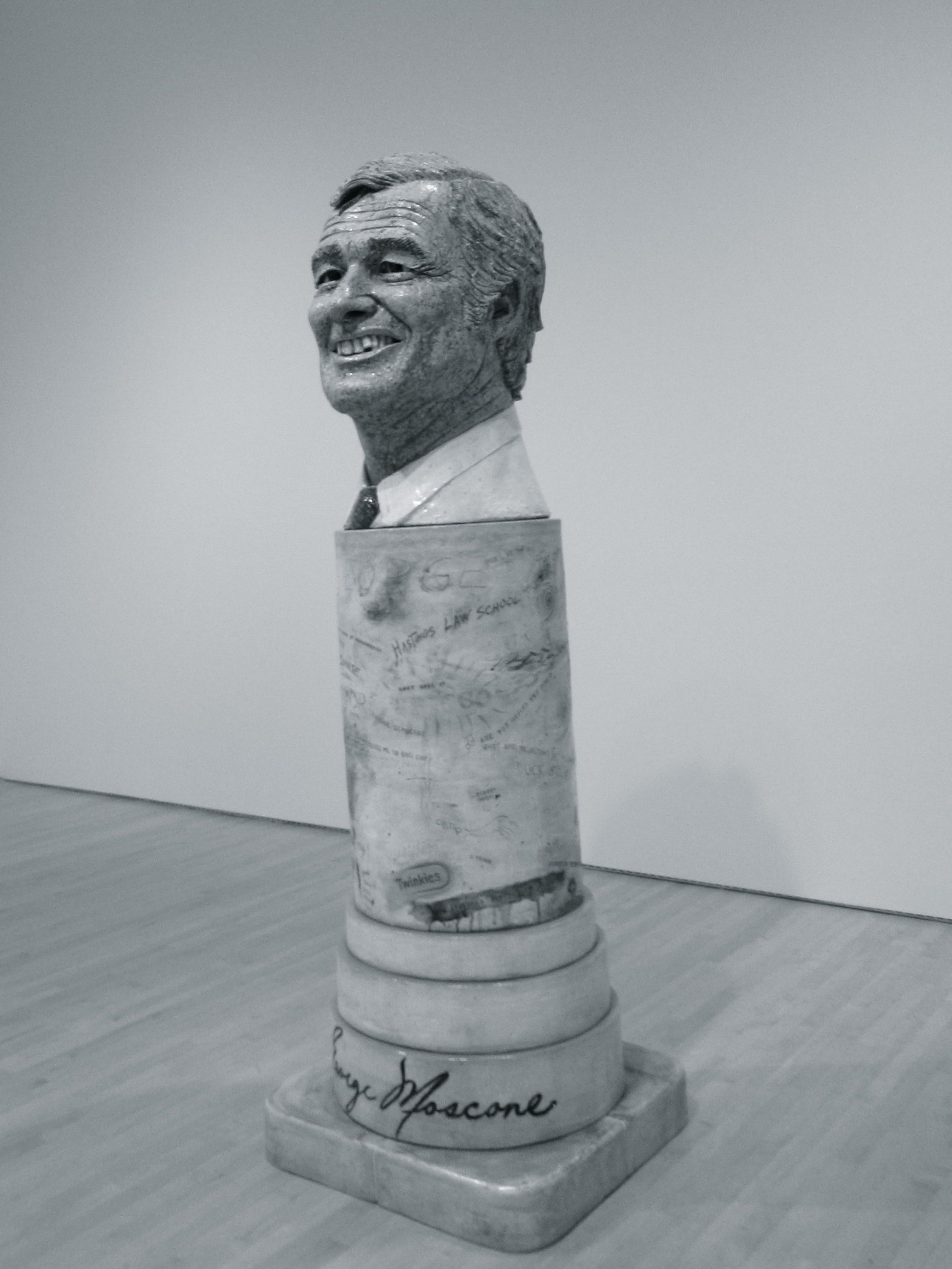

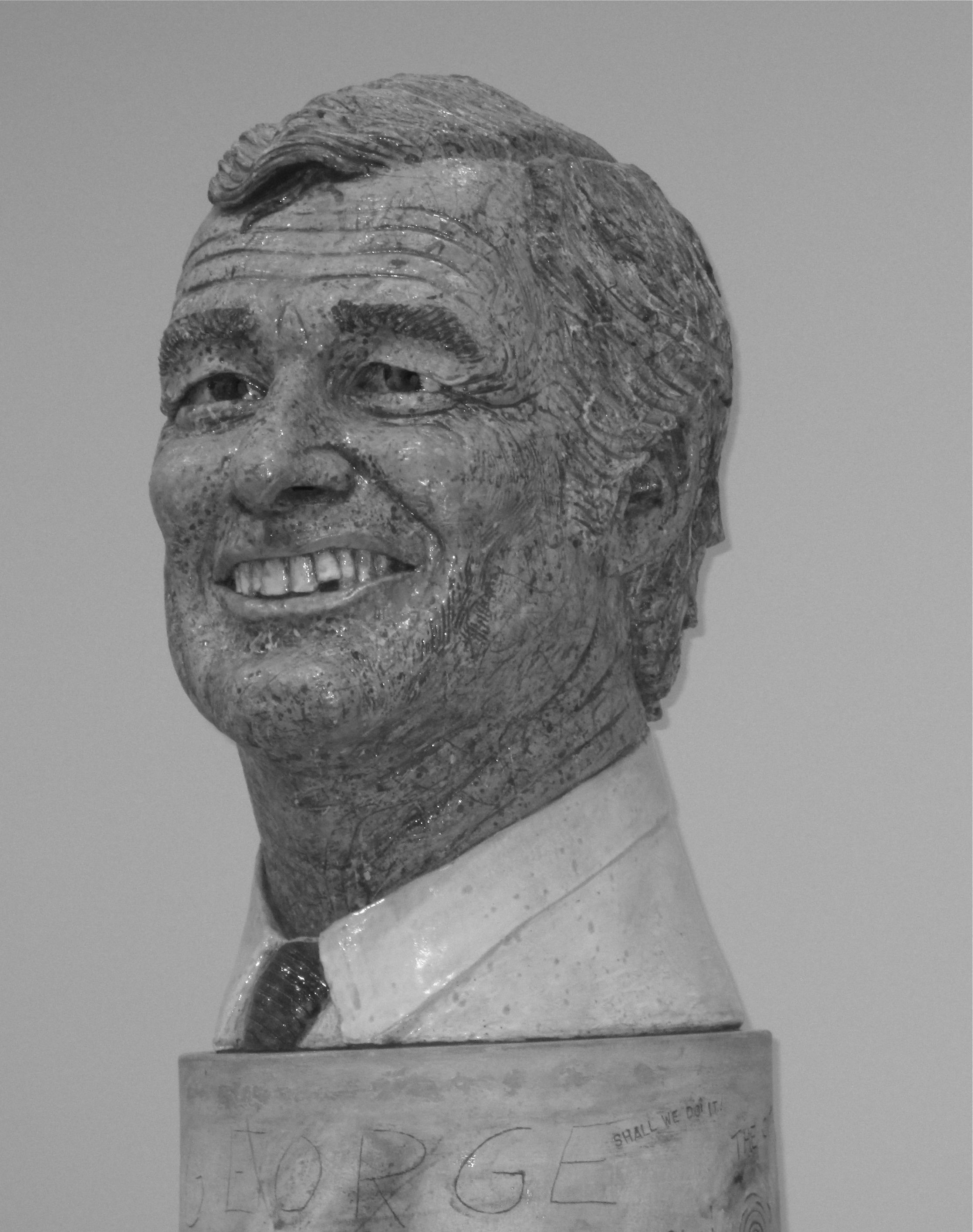

On a recent visit to San Francisco, my hometown, I visited the San Francisco Modern Art Museum. One room contains sculptures and paintings by the artist Robert Arneson. In one sculpture, Arneson deftly interprets the assassination of Mayor George Moscone in 1978 (see fig. 2). (Gay rights activist and Board of Supervisors' member Harvey Milk was also murdered.) Arneson had been commissioned to create a memorial for Moscone.

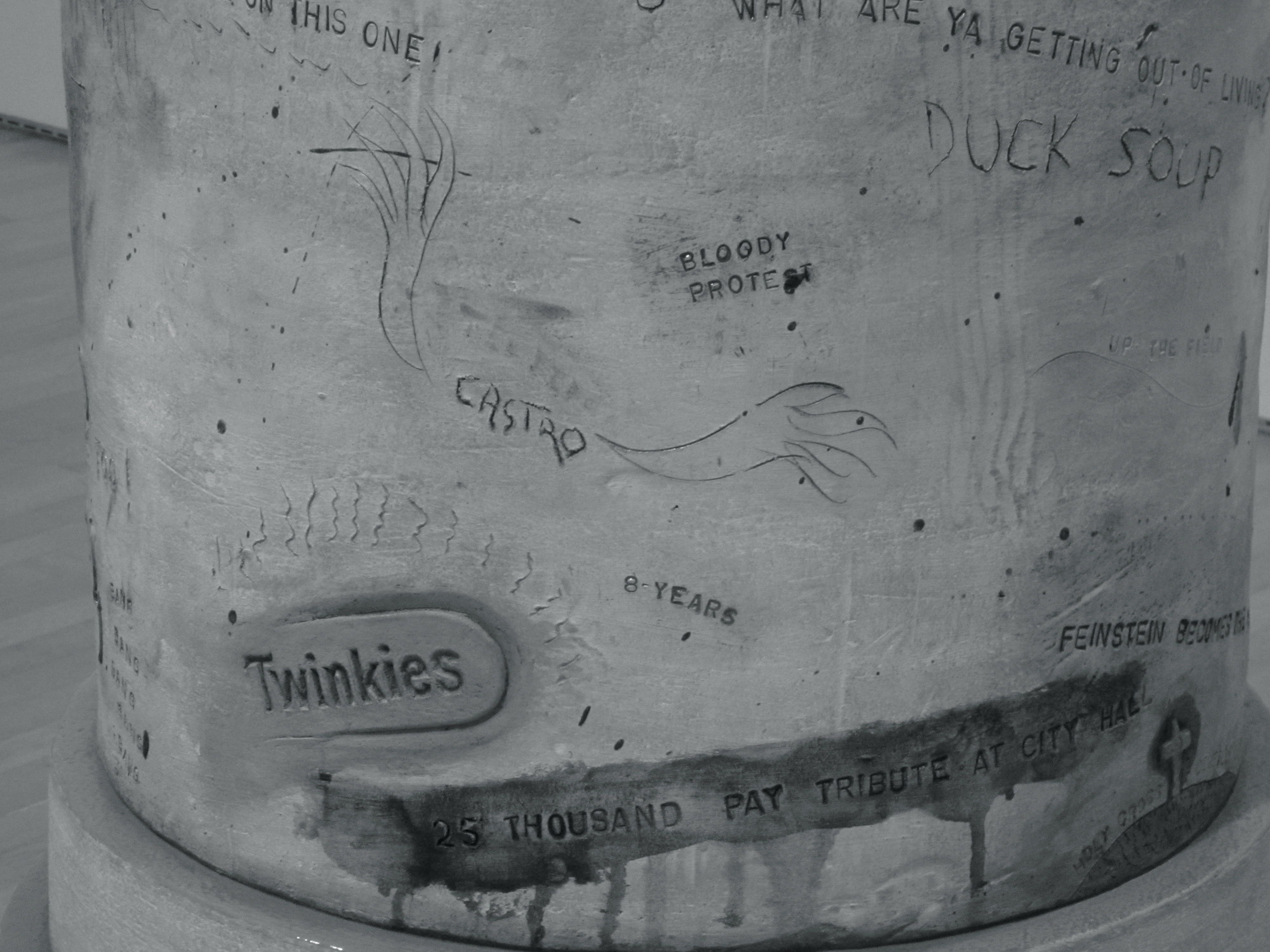

The sculpture was unveiled at the convention center in 1981, and reactions to it were overwhelmingly negative. The smiling image of Moscone, unflatteringly photo-realistic, was bad enough as memorial but the pedestal inspired the most outrage (see figs. 3 and 4). The pedestal includes images of the handgun that killed Moscone and Milk, along with a Twinkie to represent the infamous “Twinkie defense” that Dan White, their assassin, a disgruntled San Francisco supervisor, used in court. Arneson's bust is in-your-face dissent: it refuses to sanctify a memory but instead recreates the ugly violence and horror of Moscone's and Milk's deaths. The pedestal of the bust is riddled with graffiti, a Twinkie as a missile references Milk's assassination, and the words "Bang, Bang, Bang, Bang" are carved in roughly.

The sculpture was hastily covered back up and warehoused for years until a private collector purchased it. Thirty years later, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) is able to display Arneson’s sculpture in a quiet room of the glass-and-steel museum. As Jesse Hamlin, a reporter for the SFGate, explained,

Putting the statue in a museum also prepares a viewer in a way that a hallway in a public building never could. A museum goer expects the off-key and original, sometimes jarring and disturbing in presentation. The right setting is everything. (Hamlin)

This sculpture becomes safe to view, then, once displayed in a setting in which expectations are met. The museum setting distances the viewer: an aesthetic space where quiet voices murmur, where hands may not touch, and where security guards eye visitors to ensure compliance.

But it’s not only the right physical space, it’s also the right temporal space. That’s kairos: the opportune moment. Three years after the terrible assassinations of Moscone and Milk was too soon to display Arneson’s sculpture. Its angry voice has been stilled by time. Put another way, thirty years later, the kairotic moment had arrived: the display of the bust as art object was successful.

Yet, more than an opportune moment in time, the space itself is kairotic because it permits the experience of the image in such a way that we can be persuaded. The image’s rhetoricity is contained within our temporal experience of place. In the museum space, viewers linger. They pause. They circle the sculpture and pause again. This sculpture can effectively persuade us of the terrible violence of those days in 1978 because we can linger.

Here, time is experienced as duration. The viewer may stand as long as they like on the highly polished floor reading the pedestal. They may walk round and round Arneson’s sculpture according to their desire. The relative stability of the setting—the site of display—ensures a particular experience of the object.

Another way to think about this is through Walter Benjamin’s notion of aura. I take my cue from Hannah Arendt’s observation that “what profoundly fascinated Benjamin from the beginning was never an idea, it was a phenomenon” (qtd. in Benjamin 12). Benjamin describes the aura as “that unique phenomenon of a distance” (222) and suggests that both historical and natural objects possess aura. Original objects possess aura, and it is the age of mechanical reproduction, says Benjamin, that has worked to erase aura. An original object has a “presence in time and space…[a] unique presence wherever it happens to be” (220), and what I’ve described so far certainly meets this requirement. Most crucially, Benjamin argues that the meaning of objects situated in aura is informed by ritual and tradition, unlike the meaning of the reproduced object. Instead, says Benjamin, the reproduced object's meaning is “based upon another practice—politics” (221). The museum display of Arneson's bust, informed by the tradition of museum spectatorship, allows the viewer to experience aura. Its unique presence in time and space may disturb. But the display is unlikely to provoke active dissent. Participatory internet memes, on the other hand, are always reproduced objects. In order to examine these rapidly circulating, reproducing objects native to the Internet, I accept Benjamin's call to interrogate the practice of politics. I return to this in the following section.

Tap Root

The contemplative and quiet museum display may provoke joy, anger, distaste, sadness, and wonder. Some viewers may share their emotions in hushed voices. The story of the Moscone bust, that is, the dissent it sparked in a public space when the memory of violence was raw, contrasts with its silenced presence in the glass and concrete museum. This contrast suggests the significance of time and space in resistance projects.

The definition of classroom participation informs and is informed by the moment and by the space, as Critel notes. Similarly, visual rhetorical compositions, whether works of art or memes, may define and be defined as dissent at particular times and places. But memes, unlike the singular work of art, thrive on reproduction and circulation. And, as I will show, memes may sometimes incite dissent. How do the topoi Critel identifies—technology, embodiment, and community—inform participatory memes enacting or calling for dissent?