The Casual Cop and the Pepper Spray

Participation is a strategic, embodied performance.

Student demonstrations at the UC Davis campus have occurred with more and more frequency since 2009 when the regents raised tuition 32% because of state budget cuts. Student activists on other UC campuses were also protesting during this time: cuts to the UC system have ranged from forced furloughs for faculty, to frozen salaries, to increases in class sizes, but unquestionably the dramatic increases in tuition have most seriously impacted the students. There is a lot more to say about this, but I want to focus on what happened on November 18, 2011.

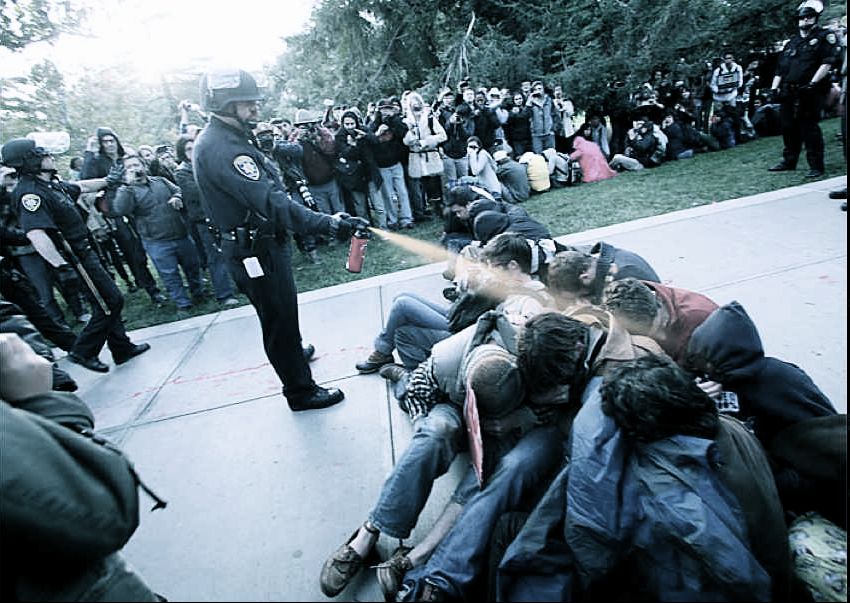

On that date, about two hundred students were engaging in a peaceful sit-down strike. According to the Davis wiki, a large group of students were seated on the ground, arms linked. The students were ordered to leave by Lieutenant John Pike of the UC Davis police ("November 18 2011 UC Davis Police Response to Occupy US Davis"). When the students did not leave, Pike along with another officer, began pepper spraying (fig. 7).

A number of very important things happened after this, among them an amazing silent protest by UC Davis students and faculty at the chancellor’s lack of response to this episode of police brutality, the “walk of shame” as students and faculty call it.

As in the case of the violence against Andrew Meyer, media-produced video and images sparked the emergence of a widely circulated meme. These images pluck the figure of Pike pepper spraying students from the images and set him into contexts that bear no relationship to the actual context. We don’t hear the screams of the pepper-sprayed young people, the shouts of outrage of nearby students, the chants. Instead we see a figure condensed into this single image: the man and his pepper spray, anonymous in his helmet, mustache and uniform.

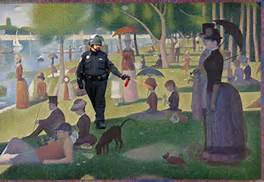

In George Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte, the pepper spraying cop casually sprays the people in the painting (fig. 8). The cop’s presence contrasts with the peaceful and idyllic painting in which visitors gaze at the water. Similarly, the cop figure is imposed in Andrew Wyeth’s painting Christina’s World. In the original painting, a young woman lying in a field stares longingly at a farm house in the distance (fig. 9). This meme disrupts the moment of contemplation. According to Know Your Meme, the Seurat image appeared two days after the pepper spraying on a Tumblr blog (Casually Pepper Spray Everything Cop).

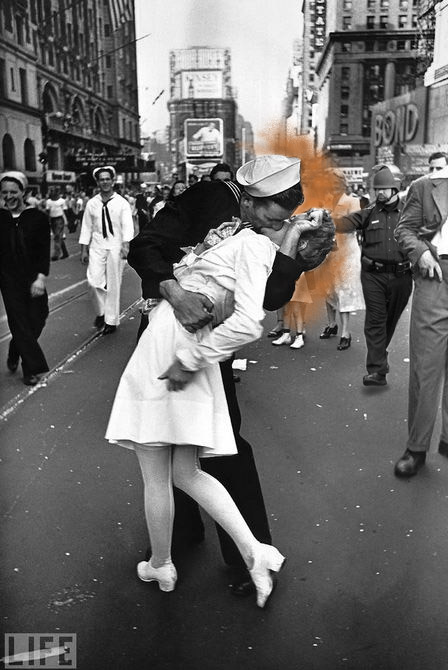

At about the same time, another group of pepper spraying cops appeared in less subtle messages about police brutality. These included the iconic photographs Tank Man of Tiananmen Square (fig. 10), the V-E Day Kiss (fig. 11), and the self-immolation of a monk protesting the oppression of Buddhists in Vietnam (fig. 12).

Like the Don’t Tase Me, Bro meme, these images circulated rapidly and globally. Like the earlier meme, these instantiations are meant to be read in the blink of an eye, a moment in time to see, recognize, laugh at, and move on.

But these images, unlike the textual meme, also do something else. By deliberately ripping into an iconic image—an object that, as Benjamin puts it, possesses aura and authenticity in the original—these meme composers make a rhetorical argument.

Last spring, I showed a class of undergraduates these images. They laughed. Only two or three of them had any idea about the genesis of these memes, but those two or three quickly explained the story to the class.

Then I showed my students the video of the original incident.

Then I asked them about the meme’s meaning. They quickly agreed that it was “making fun” of Pike. But I was startled at how rapidly they came to consensus that the meme was not just making fun of Pike. The meme was making an argument about police brutality. Pike’s casual pose against aesthetic and iconic backgrounds had layers of meaning; it had implications about violence and the police and about resistance in general.

This meme, despite its compressed temporal space, does not squeeze meaning into one dimension. Instead, its time horizon, while not infinite, tethers itself to the sign. It has political potential. I build on Benjamin’s notion that “by building many reproductions, it [the reproduced object] substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence. And in permitting the reproduction to meet the beholder or listener in his own particular situation, it reactivates the object reproduced” (221).

Might "meeting the beholder or listener in his own particular situation" suggest a condition for participation?

Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites’s analysis of iconic images is helpful here. Hariman and Lucaites focus on photojournalism images that have circulated widely and been appropriated frequently. These include images such as the Napalm Girl from the Vietnam War, the Migrant Mother taken during the Great Depression, and the Kent State image taken of a young girl screaming over the body of a dead student. While the authors focus on the American tradition of photojournalism and limit their scope to particular American iconic photographs, the most widely circulated pepper-spraying-cop meme images appropriate iconic photographs. Hariman and Lucaites identify five possible vectors of influence on the circulation and popularity of iconic photographs. These are "reproducing ideology, communicating social knowledge, shaping collective memory, modeling citizenship, and providing figural resources for communicative action" (9).

The pepper-spraying-cop meme operates within two vectors of influence: reproducing ideology and modeling citizenship.

The pepper-spraying cop, body and face anonymous behind helmet, glasses, mustache, and uniform and pasted into wildly inappropriate paintings, becomes an archetypical symbol of oppression because of his repeated appearance in scene after scene.

While some viewers may not recognize the narrative attached to the image, they do recognize it as oppression personified. In addition, the removal of the students—that anonymous, huddled mass—from the meme images ensures the pepper-spraying cop is a widely acceptable symbol of oppression. He is no longer spraying college students, whom some may find to be “too liberal” or “too spoiled.” He is spraying things everyone values and thereby reproducing ideology: the Constitution, the Tank Man, the joyful kiss on V-E Day, even beautiful bucolic paintings.

As Hariman and Lucaites remind us, “To account for the full range of appropriations and to fully understand the rhetorical potential of the icon, one has to shift from a focus on representation to civic performance” (111).

This meme, as civic performance, reminds viewers that dissent, while complicated, is also reasoned and thoughtful. Many of the most popular memes specifically evoke classic images of American civic identity—the Declaration of Independence or iconic paintings identified as aesthetically beautiful—“spoiled” by the intrusion of oppression. The meme calls to notions of civic decorum and argues that decorum will be ruptured by the anonymous figure of the pepper-spraying cop. In other words, it models citizenship—that is, citizenship in an expressly American fashion.

This argument is a safe one ultimately. Dissent is not bloody. Dissent is not the terrified faces of beaten protesters. Dissent is about holding true to shared values and the shared fear that oppression ultimately will rip into and destroy those values. So this meme does not make us uneasy about dissent. Paradoxically, the meme's safely American dissent may make it an effective persuasive strategy. It provides what Hariman and Lucaites refer to as “the illusion of transparency,” free of the network of associations and questions I have previously detailed, simply reminding the viewer just how un-American oppression can be.

If this were all, claiming this meme as dissent seems a stretch. Modeling citizenship and invoking values that reproduce ideology do not necessarily translate into strategic embodied performance. Yet, students recognize the argument of this meme immediately. The warrant that choosing dissent is an ethical move goes unquestioned. Discerning the right place and moment for dissent will be more contentious; but that discussion assumes the value of and right to dissent. Put differently, millennials can imagine themselves as protesters. They can participate in dissent and identify with the students whose pepper spraying led to this meme. They actively disidentify with the static figure of the casual cop. In the next section, I explore the implications of this argument.

[Go to "The Currency of Emergent Participatory Economies"]