Composing New Narratives, Creating New Spaces: Constructing a Learning Commons with a Wide and Lasting Impact

Justin A. Young, Eastern Washington University

Introduction

Overview

Learning Commons

Student Success

Collaboration

Conclusion

Openness

Flexibility and Sustainability

Visibility

New Cultural Narratives

Over the course of developing and implementing the Learning Commons, several crucial decisions about design were made, based on a pedagogical vision focused on student learning, research on the development of other Learning Commons, and logistical concerns. In this section, the impact of these decisions will be discussed, suggesting that such approaches may be crucial to the early success of the EWU Learning Commons, and therefore are important concerns to any campus undertaking the project of creating a sustainable next-gen learning space. Finally, the development of a new cultural narrative for learning spaces based on these approaches will be discussed.

Original conceptions of the EWU Learning Commons involved barriers between the individual programs occupying the Commons. There was a sense among some involved that such walls were needed to ensure that the kind of work previously done by the involved programs could be continued. While we anticipated that those working in the Commons would have to adjust, the decision was made to keep the Commons “wall-free.” Inman (2010) noted that a totally open and flexible multiliteracy center may not suffice for the wide range of multimodal literacy activities (sound recording, for example) that could occur in such a space (p. 24). We have taken the kind of zoning approach to design he suggested, recognizing that later phases of the Commons will need to include enclosed spaces, while deciding that, for the kind of activities that will take place in “Phase One” of the Commons, an open space would work. This decision, at this early point, appears to be crucial to the Commons' early success. The Learning Commons is consistently filled with students, from morning until night. In fact, so many students spend time in the Commons that new tables had to be ordered so that programs like the Writers’ Center and PLUS have enough work spaces. This openness has created a shift in the way students are making use of and interacting in the programs that occupy the Commons. Students who never set foot in the Writers’ Center in its previous location are now walking through it, or sitting down and studying next to other students who are in Response sessions. The openness of the space facilitates the kind of active, collaborative learning that the Writers’ Center already promoted. Now, the constructivist, student-centered learning (as promoted within Tagg’s Learning Paradigm) is happening out in the open, and spontaneously. The open space of the Commons is encouraging students to come to the Commons for their own learning needs and to use that space in a variety of different ways.

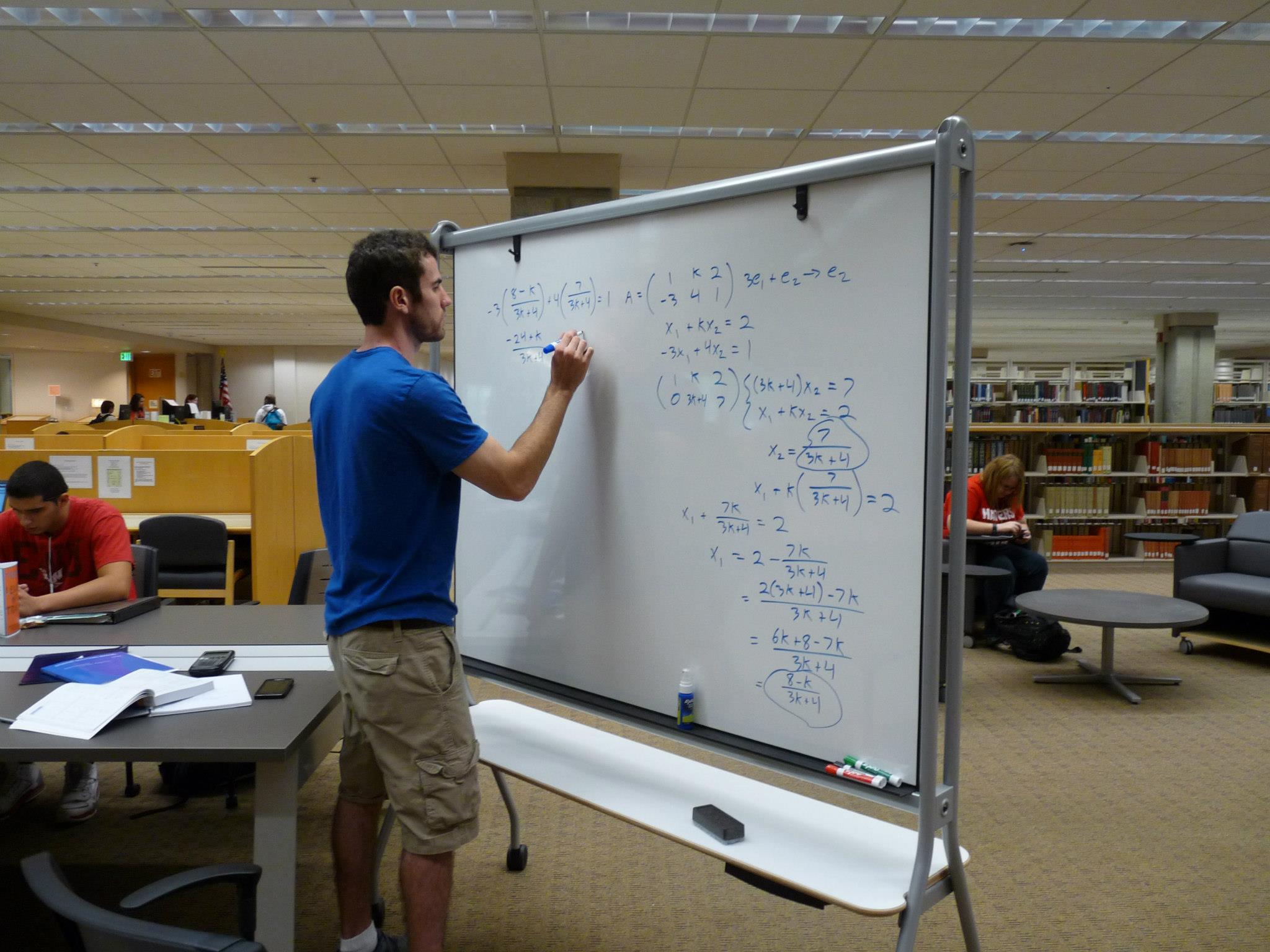

Central to the planning of the Learning Commons were the concepts of flexibility and sustainability, both on a micro and macro level. On the micro-level of daily use, the Commons provides flexibility to all of its users through its open design and its mobile, multi-purpose furniture and technology. Students are free to use any available space in the Commons; likewise, staff members working in the Commons are not constrained by a defined area, so one-on-one and group appointments can be held in any number of different locations within the learning space of the Commons. Further, the furniture facilitates the dynamic nature of the collaborative work done in the Commons, as it is primarily mobile: almost every piece of furniture in the Commons has wheels. Mobile whiteboards placed throughout the Commons provide not only a surface for communication during collaborative study sessions, but are also used to create new spaces within the Commons.  These whiteboards create semi-private spaces for small groups, demarcate the boundaries of academic programs, and even create specific pathways to help direct traffic within the Commons.

These whiteboards create semi-private spaces for small groups, demarcate the boundaries of academic programs, and even create specific pathways to help direct traffic within the Commons.

Figure 15: Students make frequent use of the mobile whiteboards as a tool for learning, as well as means to create more private space.

The Learning Commons is also flexible from the perspective of macro-level planning. The Commons was developed with the idea that the space would be created in phases, expanding and changing according to need. Everyone involved understands that the Commons will evolve and is unlikely to be the same in subsequent phases of development. While this kind of flexibility may at times lead to feelings of instability among those working in the Commons, it also helps ease anxiety over those things that are not working. If something is not working in the first phase of the development of the Commons, we know that changes can be made to address the issue. This inherent flexibility increases the sustainability of the Learning Commons project. In other words, if student or university needs change, the Commons does not have to shut down; it needs to be revised or rethought in order to meet new challenges. The Commons is built to change and is therefore more likely to survive and evolve with changes in overall university structure and priorities.

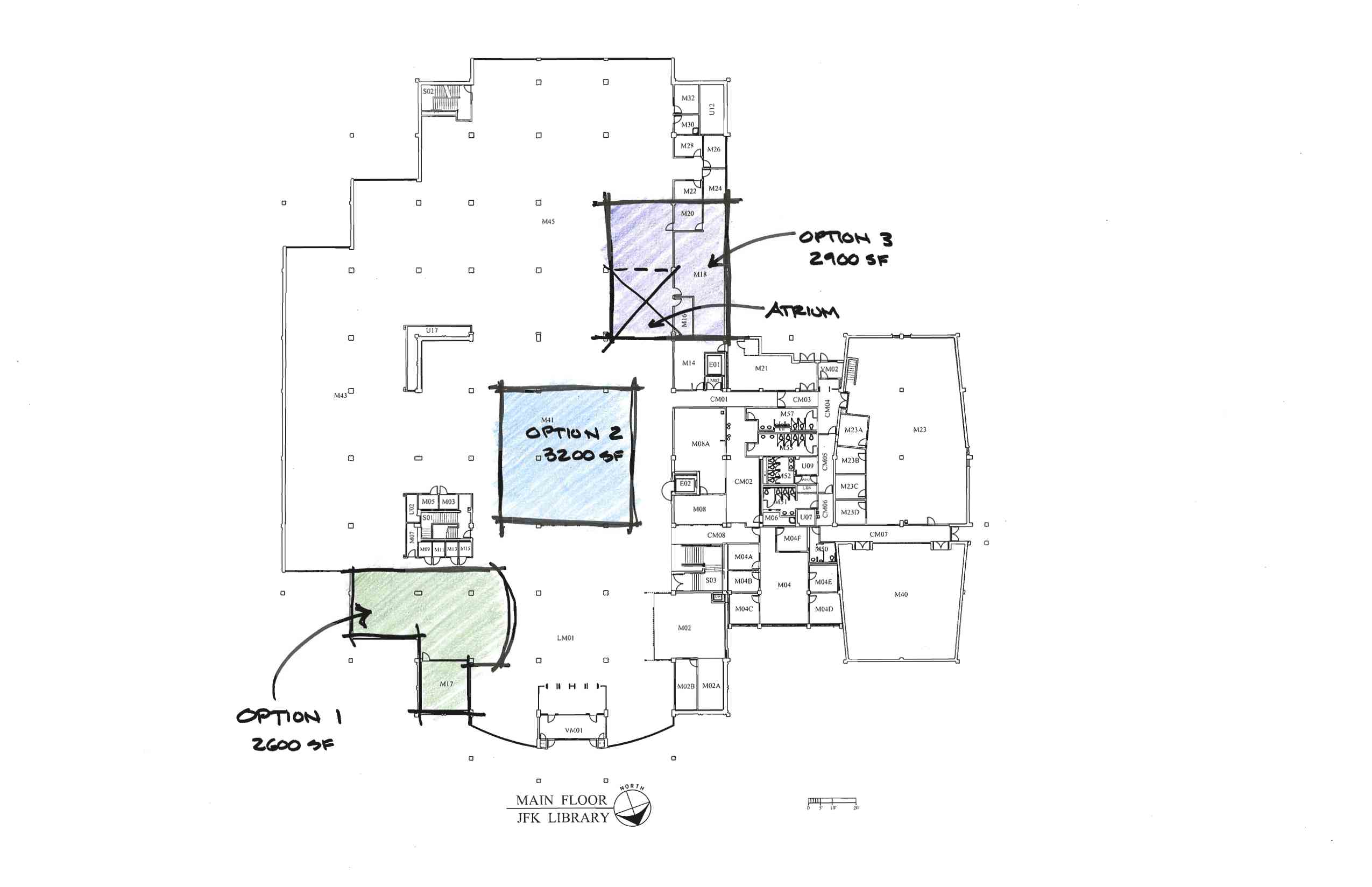

Figure 16: Drawing of three possible locations for the Learning Commons on the main floor of library.

The central, visible location of the Learning Commons is an essential element of its success so far. Numerous locations within the library were considered for the Commons, including the lower and upper levels of the library. For an image of what the Learning Commons might have looked like if it were created in three different areas on the main floor, see Figure 16. The Commons ended up in an ideal location for visibility—on the main floor, visible from the main, front entrance to the library. Initially, the library expressed concerns about the location of the Commons. Numerous journals were deaccessioned from the main floor of the library in order to open up this space, and a number of student-use computers had to be relocated. Further, the decision to locate the Learning Commons in an open rather than enclosed space was crucial to the visibility of the Commons. Early concepts for the Writers’ Center relocation to the library, for example, included the move to an enclosed, unused area of classroom and office space. For an understanding of what that would have looked like, refer back to Figure 5, which represents the layout of the current Commons. This early proposal would have set up the Writers’ Center within the space occupied by Commons administrative offices and math faculty offices. While this plan would have allowed the Writers’ Center to continue to do its job as it had been done in its previous location, with less need for adjustment and rethinking, the center would certainly not have been as visible. It is unlikely that moving the Writers’ Center to a new, enclosed space in the library would have resulted in the kind of increased usage seen in the first two years of the existence of the Commons.

As discussed above, both universities and writing centers are shaped and defined by the values and narratives of outsiders, or those not directly involved in these institutions themselves, but with the power to influence their actions. The university may be constrained by a narrow definition of student success that only takes into account graduation rates, in the same way that a writing center can be constrained by an understanding of writing that primarily takes into account grammatical correctness. In response, both of these entities tell narratives about themselves, in an effort to reframe the issue or correct misperceptions.

North’s (1984) “Idea of the Writing Center” outlined the difficulties of the marginalized writing center. Others, including Andrea Lunsford, echoed North’s narrative of the problem and called for a process-based, collaborative response. Lunsford (1991) drew from Berlin’s narrative (1987) on the history and development of the field of composition and rhetoric to suggest that writing centers are often perceived to operate on the basis of two faulty narratives about writing “the Storehouse” (based on what Berlin [1987] called Current-Traditional Rhetoric) and/or the “the Garret” (based on Berlin’s [1987] articulation of Expressivist Rhetoric). In the first narrative, writing is valued as a means for effectively storing and delivering information; in the second version, writing is understood as an individual pursuit, as represented by the story of the lone writer toiling in an attic by candlelight, inspired by individual genius alone. Writing Centers based upon or viewed through the lens of either representation of writing can be understood as marginal to the scholarly process of knowledge creation, believed to be the real academic work of the university. The new accepted norm for writing center practice underscores the idea that writing is a collaborative act, and the writing center session should be based on dialogue designed to facilitate the student’s growth as a writer. The purpose and practice of the writing center has been misunderstood, the story goes; once the university can be made to understand this real purpose and approach of the center, it will be brought in from the margins and appreciated for the valuable service that it is.

In many cases, that just hasn’t happened, Murphy and Hawkes (2010) argued, and so we now need a new cultural narrative that goes beyond this preoccupation with martyrdom. They suggest that the emergence of multimodal communication as a writing center concern may offer the means for creating new, more effective narratives. A new narrative, however, is also arising from something perhaps more elemental than the current drive in the writing center field to provide feedback on digital and visual texts. There is an increasingly connected nature in our emerging network culture of human relations, work, and academic disciplines. In a learning space, we must develop what we do in response to the network of relations that comprise that space. As Mark Taylor (2004) argued, if there is, in fact, progress in history, it is toward increasing complexity. This narrative of increasing complexity—of increasing difference alongside increasing interconnectedness—must inform how educators understand knowledge and promote learning in the 21st century.

The challenge for those who work in learning spaces such as a writing center or a learning commons is to determine how this narrative can be put into action. Geller et al. (2007) suggested one approach in The Everyday Writing Center. Instead of defining our community/workplace/Writers’ Center by its training manuals or policies and procedures, and instead of “fetishizing” commodities “like time, normalized practices, identifiable policies,” we need to focus on our daily actions and interactions as they are happening in order to create the kind of learning community—what they called a “community of practice”—that we want (p. 9). We would then focus on the everyday actions, on what we do, in order to develop “a praxis compellingly situated in the relationa—not as things, but as ways of acting with and for one another” (p. 9). (The reflective activities our Writers’ Center staff engaged in around our mission and goals are an example of this kind of work.) The new cultural narratives that emerge out of next-gen learning spaces from this view, then, may not just be about the new technology that we fill these spaces with, but about the dynamic relations that emerge when enclosed spaces are opened up and redesigned to maximize connection and flexibility.

The design of the sustainable learning space can provide the physical model of the new narrative of learning that is emerging from it. A lasting, impactful, learning space will operate as an open, emergent network: the various nodes within a learning commons (the multiliteracy center, the library, academic services, etc.) will develop and grow out of the dynamic relations and interactions with other sites within and outside of the network. The open, connected space of the Learning Commons serves as a physical representation—and visual argument for—the kind of learning that leads to student success. Our students need to understand and experience how the practices of academic research and writing, the creation of quantitative information and its visual representation, and the practices of all academic disciplines are connected and intertwined. An open, networked Learning Commons enables students to participate in these “networks of practice,” while serving as a physical reminder of how these practices are connected. The interconnectedness makes the Commons more likely to succeed, as each of the nodes of the network help to sustain and support the others. One of the new cultural narratives emerging from learning spaces, then, builds upon the traditional writing center value of collaboration. This new narrative begins with two people working together and moves outward through an open networked space to connect other individuals, technologies, disciplines, and cultures in a transformational moment of learning.