Composing New Narratives, Creating New Spaces: Constructing a Learning Commons with a Wide and Lasting Impact

Justin A. Young, Eastern Washington University

Introduction

Overview

Learning Commons

Student Success

Collaboration

Conclusion

The Learning Commons at EWU was developed as one form of response to the need to improve “student success” at the University. The efforts made by leaders of the University were informed by the emerging narrative of student success in higher education: the story of improved student performance, retention, and graduation achieved through particular approaches to issues like teaching, curriculum development, and assessment, academic support and advising, for example (Kuh, 2008; Tinto, 2005). Unsurprisingly, EWU has difficulty in maintaining the kind of retention and graduation rates seen at other colleges and universities in the state. EWU is under pressure to improve both its retention rates and its graduation rates, despite the fact that it has low admission standards and a high percentage of first-gen students and has been operating in a restrictive budget environment since 2008. The question for EWU’s leaders, then, has been how the university’s narrative can, as an underachieving school, be changed to a narrative of a school that promotes student success.

This narrative of student success that framed and informed the development of the EWU Learning Commons can best be understood through John Tagg’s (2003) work, describing and promoting an ongoing shift in colleges and universities toward a more effective paradigm of education. Tagg (2003) suggested that institutions of higher education are in the process of shifting from what he calls the “Instruction Paradigm” to the “Learning Paradigm.”1 The outmoded Instruction Paradigm is based on the idea that the chief purpose of the university is to provide instruction; the university is therefore organized accordingly. The focus of the university in this model is on the production, scheduling, and filling of courses that students can take to fulfill particular requirements. These courses are designed to enable instructors, as the focus of the educational experience, to (supposedly) efficiently transfer information to the minds of the students, in classroom spaces that are designed to promote a teacher-centered, passive environment. This model, Tagg argues, is inherently flawed; he went as far as to suggest that the focus by the university on the production of courses or instruction is analogous to a car company whose mission is the production of assembly lines. He suggested that the corrective to this flawed model of education is to focus on what the actual product of the university should be: learning. Hence, he advocated a move to a Learning Paradigm of higher education, wherein student learning is the mission of colleges and universities.

This ongoing shift toward the Learning Paradigm in higher education has had profound consequences for how the university is run; the shift is also central to narratives of student success. However, the focus of any story of student success may vary, depending upon who is telling it. Following the Learning Paradigm, universities now frequently frame the success of the university itself chiefly in terms of student success, and this success is often understood through student engagement and learning (Tinto, 1999). The end measures of student success (often set by entities outside of the university), however, tend to be based on more cut-and-dry numbers like retention and graduation rates.

The development of the Learning Commons at EWU is reflective of the ongoing interplay between national and state level demands on the university to produce specific measurable results and “on-the-ground” efforts to improve student engagement and learning. The story of student success at EWU could indeed be told with either perspective in mind; in fact, EWU’s story could be told as an account of how the constraints of a retention-focused understanding of student success have inspired an effort to improve student engagement and learning. Indeed, the story that we will hopefully be be able to tell will be about how the push to improve retention and graduation rates at EWU resulted in a clear and effective move away from producing instruction and towards the creation of student learning. Whatever the long-term outcomes, and whatever narratives we tell in the future, the creation of the Learning Commons is currently the most tangible effect of the ongoing efforts at EWU to improve student success, and it operates in a manner consistent with Tagg’s insistence on learning as the chief work of the university.

As noted above, the EWU Writers’ Center was involved at the very beginning of this process, as it was slated to move to the library as a single entity before the concept of the Learning Commons began to be officially developed. In fact, the process by which the various entities involved in the Commons project shifted from a focus on moving a single entity—the Writers’ Center—into the Library, to the eventual development of a Learning Commons involving numerous programs, is illustrative of the kinds of challenges, tensions, and mindset changes that arise over the course of this kind of endeavor.

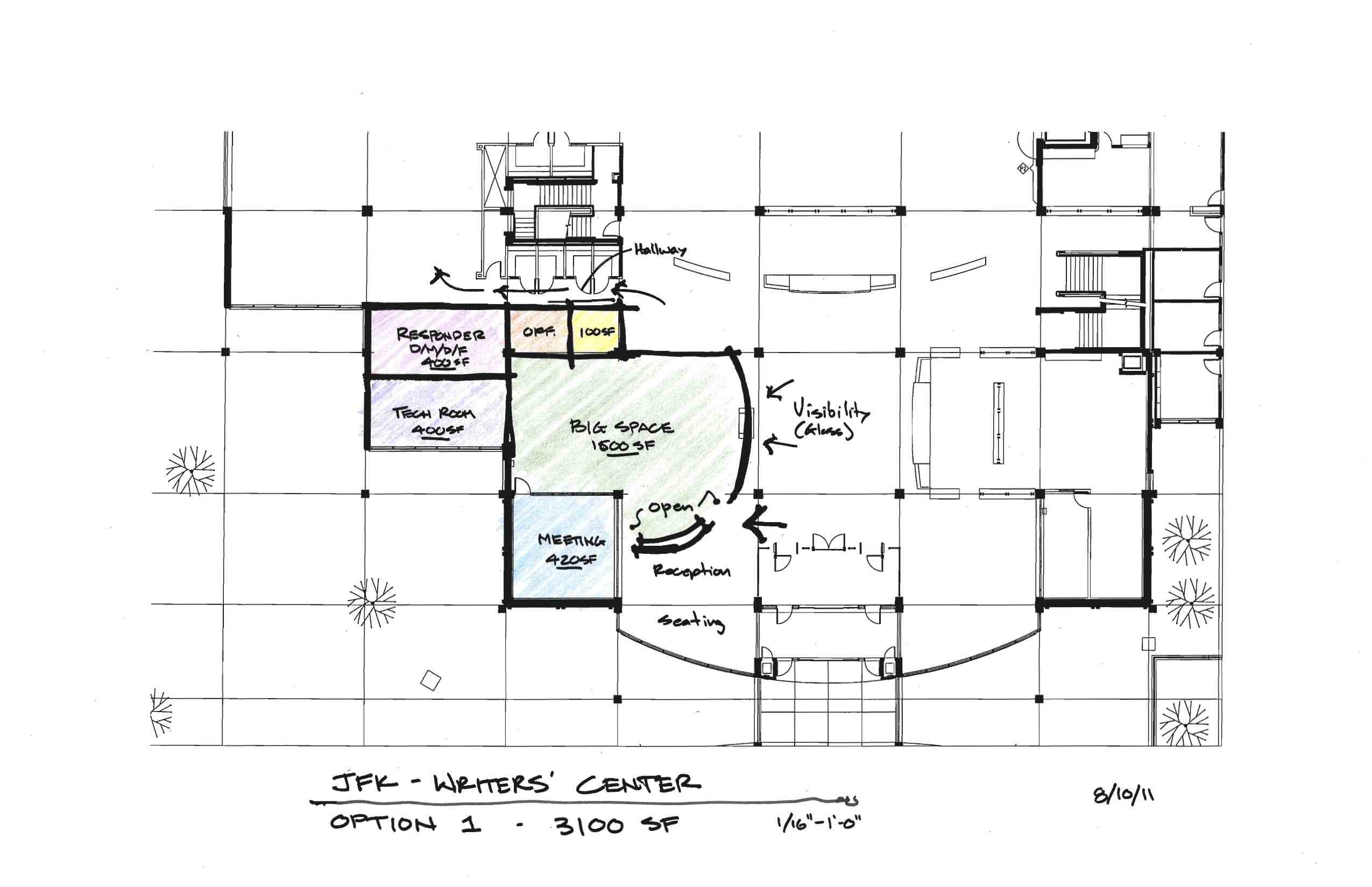

The Writers’ Center’s move to the library and eventual creation of a Learning Commons began (at least for the Writers’ Center) with a call from the then Dean of Libraries. He called me directly and unexpectedly, and with little introduction, asked, “What do you think about moving the Writers’ Center to the library?” What followed was a series of one-on-one and small meetings with the library leadership that eventually led to a “kick-off” event that brought library staff and the Responders together to meet, talk about their roles, and share ideas about collaboratively creating a space for the Writers’ Center in the library. The two groups, along with facilities personnel worked together for almost a year to develop a vision, determine a location for the Center,  and to eventually draw up preliminary plans (see Figure 12).

and to eventually draw up preliminary plans (see Figure 12).

Figure 12: An original concept for move of the Writers’ Center on its own into the library.

The original concept was for the Writers’ Center to be placed just to the side at the main library entrance. This would position the Center for maximum visibility, as it would be immediately visible to students as they entered the library; further, the Center would be across from the reference desk and circulation desk, particularly high traffic areas in the library. After completing serious work on the plans to move the Writers’ Center into the library on its own—from collaborative workshops, to consultation with facility planners, to internal efforts to get Writers’ Center staff buy-in—we were confronted with a major shift coming from the upper administration: the Writers’ Center would not be moving to the library as individual entity. Instead the Writers’ Center, along with several other student support programs, would all be moving into the library to create a “Learning Commons.” While this was not an unwelcome idea, it was an abrupt and radical departure from what we had been planning, and so it required all of those who had been involved up to that point, myself, the Dean of the Libraries, the Writers’ Center staff and the librarians, to dramatically shift our mindsets. (For more on the specific ways that the Writers’ Center staff had to shift mindsets in order to make the move to an open commons, see the section “Practice, Philosophy, Technology” on the Learning Commons page.)

As the director of the Center, I had taken an active role in the original plans to move the Writers’ Center—I made it clear from that start that moving the Center had to be used as opportunity to expand and diversify our services to students. I wanted to be sure that we could set clear objectives for student learning that involved more than just improving student writing; it was essential that the Center not just move locations, but that it was transformed into a multiliteracy center. As the university’s focus shifted to the development of a Learning Commons, I took a central role within the leadership group charged with developing the Commons. My chief goal was to ensure that the creation this new space would be informed by a clear pedagogical approach to student learning, and that the concept of the multiliteracy center would inform all of the services that would eventually form the commons. A central concern in any project to build a learning space is the tension between material-focused planning (logistics, deadlines, funding) and the need for that planning to be informed by a pedagogical purpose or philosophy.

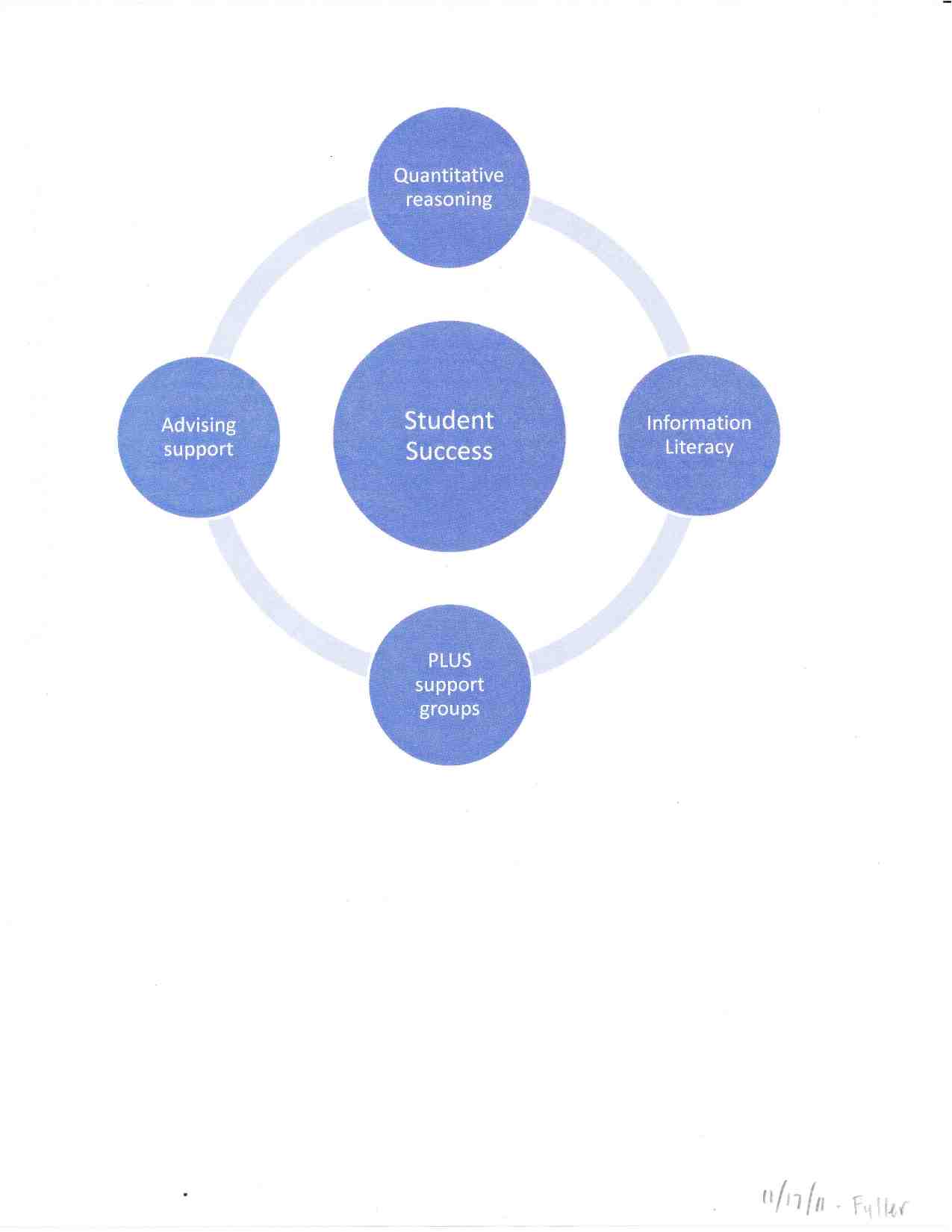

At the first Learning Commons planning meeting of a select group of administrators, faculty and staff, the Provost formally gave his charge: create a space in the library that would bring together a set of student support programs, which were, at that time, located at various locations scattered across campus. This, he argued, would improve access to these services by co-locating them in a visible, central space on campus. The Provost presented a diagram to illustrate what he had in mind:  it was a circle with various student service programs around it, with the phrase “Student Success” in the middle (see Figure 13).

it was a circle with various student service programs around it, with the phrase “Student Success” in the middle (see Figure 13).

Figure 13: An original concept for move of the Writer's Center on its own into the library.

I then presented a white paper, “The EWU Multiliteracy Center: The Foundation of a Learning Commons” proposing that the Writers’ Center be expanded into a Center that provided feedback on digital and visual as well as traditional alphabetic text; this document also argued for the inclusion of other specific entities within the Commons, and suggested that the Writers’ Center’s approach to promoting student multiliteracies be used as a model for Learning Commons as a whole. The paper suggested that the Commons include programs devoted to quantitative literacy (math support), technological literacy (Multimedia Activities Resource Services, or “MARS Lab”), academic literacies (advising and PLUS) and information literacy (the library). I created this document on the basis of numerous discussions I had with the Dean of the library. We had spent a great deal of time working on the idea of moving the Writers’ Center to the library; I wanted the work that we had done, particularly in terms of the relationship between space and the facilitation of student learning, to inform the development of the Commons.

The pitfalls experienced by other emerging multiliteracy centers, like the one described by Sara Littlejohn and Kimberly Cuny (2013) at UNC Greensboro, informed decision-making on this project, as I wanted to ensure that the collaborative, student-centered approach to learning practiced by the Writers’ Center would inform the design of the new Learning Commons space. Littlejohn and Cuny experienced the disconnect between how space looks and what it should do. As noted by James Inman (2010) in “Designing Multiliteracy Centers: A Zoning Approach,” new learning spaces often appear to be “designed around furnishings and technologies” (p. 20). I knew that the move of a learning space like our Writers’ Center into a new space should not and could not be simply a change in the location of its services; the planning of such a move should not just involve what will stay, what will move, and where to put the things that are moving. I saw it as an opportunity to reinvent our program, to reflect upon and rethink what we did, while building upon what worked well. The vision of a new learning space for an existing academic support program should be created in the most reflective manner possible; the move to a new space changes what a program does. Some of those changes can be anticipated, and some cannot. The final, concluding section will detail the most important decisions made about the design of our learning space. The impact of those design decisions will be discussed in relation to an emerging approach to understanding the relationship between space and learning. This perspective may help to generate the kind of new cultural narrative advocated by Murphy and Hawkes.