Composing New Narratives, Creating New Spaces: Constructing a Learning Commons with a Wide and Lasting Impact

Justin A. Young, Eastern Washington University

As I am the director of the Writers’ Center involved in the development of the Learning Commons under discussion, the perspectives of the Writers’ Center and the narratives that are told about it (and by it) are central to this account of the creation of the Learning Commons as a whole. The Writers’ Center, prior to its involvement in the Learning Commons project, was unique in some ways and typical in others. Its uniqueness will be discussed in detail in another section, but it is necessary now to point out a few important features of the Writers’ Center. The Center maintains a professional rather than peer staff, hiring mostly those with Masters’ Degrees and above, with extensive experience in academic and/or creative writing. These staff members are called Responders, rather than tutors or consultants. This title and its unique name—Writers’ Center—itself is reflective of its student/writer-centered philosophy. In comparison to my experience as the director of two other writing centers, the EWU Writers’ Center is particularly devoted to this philosophy and specific method for providing feedback (more on this below).

The Center was subject to the same challenges faced by any other writing center. The cultural narratives surrounding our center were similar to those at other institutions. Our center, like many others, struggled against the stigmatization of the space as a place for remediation, as a place primarily to send struggling writers or English Language Learners. It faced the common idea that writing centers are fix-it shops, a place where writing could be dropped off and then picked up after errors of grammar and mechanics had been repaired; it had to defend itself when this did not happen, and students who attended the Center once did not produce error-free writing thereafter. It faced the challenge of trying to reach out to faculty and students beyond the discipline of English. In other words, one of the narratives of this center was a story familiar to anyone involved in Writing Center work, of the ongoing effort to fight against these misconceptions, to reach out for partners across campus, and to legitimize itself by making clear its actual mission and value to the university.

In “The Future of Multiliteracy Centers in the E-World: an Exploration of Cultural Narratives and Cultural Transformations,” Christina Murphy and Lory Hawkes (2010) suggested that, in order to remain viable, or better yet, become indispensable, writing centers must move beyond this common story about writing centers, what they called a narrative of marginalization as told and reinforced in Stephen North’s (1984) “Idea of the Writing Center.” North, of course, was arguing against the marginalization of the writer by pointing out how the common misconception of the Writing Center as a “fix-it-shop,” where poor-performing writers should be sent for service, works to keep centers from becoming legitimate and effective spaces of learning at the University. North (1984) argued against this conception of the writing center as a space of remediation and product improvement by suggesting that writing centers focus on creating better writers, rather than better papers. Writing center scholars, administrators, and practitioners have consistently attempted to push back against the marginalization described by North in a similar way: by promoting writing centers as spaces of inquiry and collaboration (Lunsford, 1991; Ede, 1989). Stories of such attempts fill our field’s journals, books and edited collections. Murphy and Hawkes (2010) called these ongoing, unchanging efforts—in the face of an academic culture that continues to reject them—martyrdom; most of these attempts do little to change the marginalized status of the writing center within the university structure.

As noted above, we need a new approach; the stories we have been telling about writing centers to ourselves and to others aren’t changing the way that writing center spaces are used or the way that writing center programs are viewed. “New cultural narratives” must be created to inform and inspire the development of writing centers that are central and essential to the work of the university. These new stories can be derived from the emergence of digital and visual culture, and the emerging effort of writing centers to engage in multimodal nature of communication, to become multiliteracy centers. Murphy and Hawkes (2010) promoted a vision of the writing center that functions differently by expanding its practice to include work with digital and visual texts; in doing so, they suggested that a different kind of philosophy for the writing center may follow. From this new practice and philosophy, a different kind of narrative about the writing center will emerge, one in which the writing center is valued and respected within the university as a center for creativity and innovation. At the time of this writing, the Writers’ Center and EWU Learning Commons has been open for two academic years; we have finished developing the two phases of the learning space and have developed a number of new philosophies and practices from which this new kind of writing center narrative will hopefully emerge. Below is an account of the development of the Commons from the Writers’ Center perspective in terms of space, philosophy, and practice.

The original EWU Writers’ Center was like most writing centers in that it operated within its own unique space; it was enclosed and autonomous. In many ways, it was an effective and comfortable space. Among the traditional writing centers I have directed or visited, this center had by far the best space, both in terms of size and utilization, as shown in Figure 3. The space itself was ideal for the kind of center that operated within it. In contrast to other centers I’ve seen or worked in, which were often small and already in need of additional space, this center was big and open, with plenty of room for students and staff alike. Its primary space was a large, wide-open area that contained tables for one-on-one or group response sessions. This area also included a reception desk, couches, a conference table, and student computers.  The Center had an attached office for the Director and a medium-sized room for responders to store their belongings and take breaks. The space of the Center itself was conducive to collaboration and connection among the students and staff that spent time within it. Like all of the other writing centers I have directed, and many more writing centers, however, it was an independent entity closed off from much of campus.

The Center had an attached office for the Director and a medium-sized room for responders to store their belongings and take breaks. The space of the Center itself was conducive to collaboration and connection among the students and staff that spent time within it. Like all of the other writing centers I have directed, and many more writing centers, however, it was an independent entity closed off from much of campus.

Figure 3: The original EWU’s Writer’s Center was an effective and comfortable space, with tables and chairs throughout the room.

The location of the Center on campus and its position within the administrative organization of the school did not necessarily lend itself to connections with students or university staff and faculty. While it was purposely situated within the school’s student union building, it was neither visible nor even easy to find within that building. It was difficult to even give directions for getting to it (“Go to the elevator by the bookstore, take it to the third floor, take a left, head to the right, follow along past the computer lab…”). The Center was also situated administratively in an ideal way that nonetheless limited its connection and interaction across campus. It reports to the Dean of the College of Arts, Letters and Education (CALE). This reporting structure is in many ways ideal. The Center is not tied to a department, which might have limited its ability to present itself as a Center that served students across the disciplines. Within CALE, the Center is provided the administrative support it needs, with the independence to effectively provide outreach and service to students, staff, and faculty across the disciplines. This arrangement, however, did not necessarily connect the Center to other entities on campus with similar missions of student support and service. Collaboration with other departments or programs on campus had to be taken on one at a time and involved making the initial effort of outreach.

Figure 4: The Learning Commons as seen from front entrance.

Signs demarcating individual programs in Commons can be seen on the right.

As a result of the development of the Learning Commons, the Writers’ Center is no longer an enclosed, autonomous entity. This change in space is consistent with research on the relationship between learning and space. As Brian Sinclair (2006) wrote in “The Commons 2.0: Library Spaces Designed for Collaborative Learning”:

The Commons 2.0 supports constructivist learning, a philosophy which asserts that real understanding and knowledge are constructed through personal experience and reflection rather than conveyed passively through a classroom lecture. Nancy Van Note Chism noted the “decenteredness” of collaborative learning spaces like the Commons 2.0. This model … emphasizes “co-learning and co-construction of knowledge.”

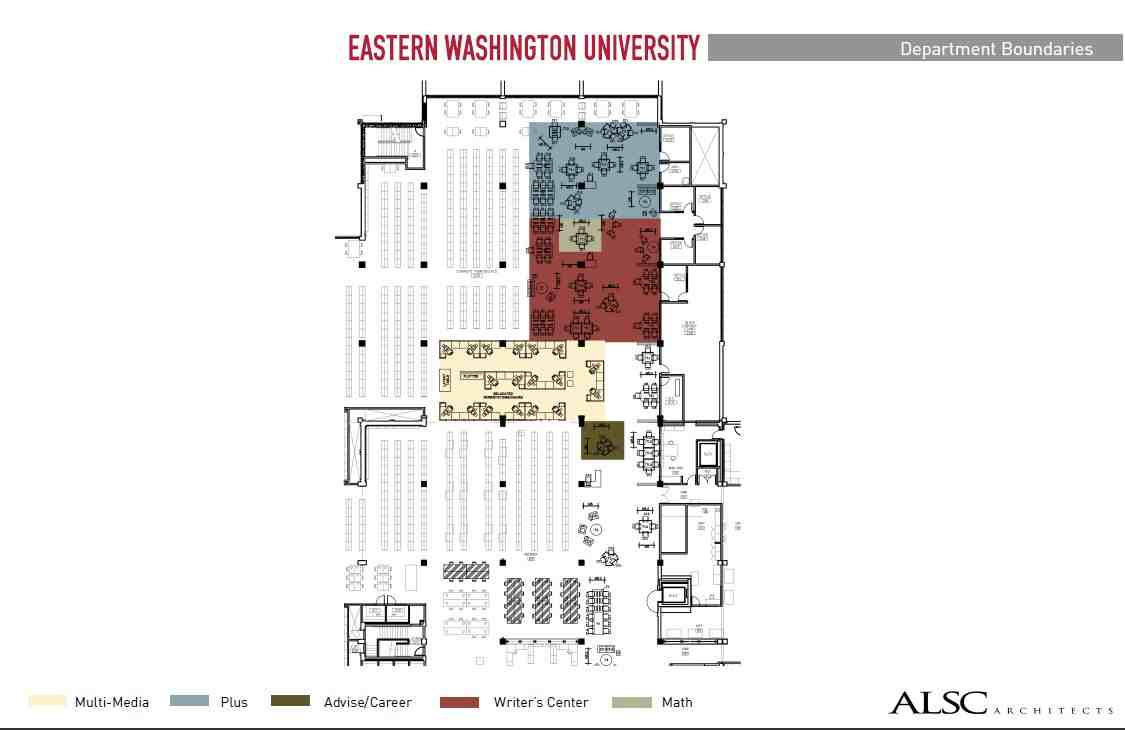

Figure 5: A proposed layout for Phase 1 of the Learning Commons that approximates the current layout. Areas assigned to individual programs are indicated by color.)

The Writers’ Center had already moved learning outside of the teacher-focused classroom, promoting it through facilitating writers’ active construction of knowledge. This constructivist learning, however, took place within a literal center that limited the kind of learning that can be done in collaboration across the disciplines and through different media of communication. Now, the Center operates in a wide-open, decentered space shared by the Multi-Media Commons, the PLUS program and, of course, the library itself. Instead of operating as an entity separate from other campus services, it operates in a network of similar opportunities like those listed above; this is what marks it as a decentered space. The Writers’ Center, as part of a decentered and open Learning Commons, is connected physically and programmatically to other student-focused programs and brought into contact with a wider range of disciplinary activities and modes of communication. In this next-gen learning space, the walls between programs have come down; the essential design element of the Commons is that it is truly an open and shared space.  Signs and service desks mark the boundaries between the first three entities; a sign at the (open) entrance to the Commons delineates it from the rest of the library.

Signs and service desks mark the boundaries between the first three entities; a sign at the (open) entrance to the Commons delineates it from the rest of the library.

Figure 6: The front entrance of the Learning Commons as seen during its grand opening. Former EWU President Rudolfo Arevelo is pictured cutting the ribbon.

The decision to create a commons without walls or barriers between different programs, which will be discussed in further detail in the concluding section, has had a strong impact on the work and daily practice of the Writers’ Center. Before detailing those changes, however, it is important to note that the most obvious and perhaps impressive change has been in its student usage. Its location in the library and visibility in the middle of the Commons has had a tremendous impact on the amount of student contact the Center makes. As noted in another section of this chapter, at the time of this writing, the Writers’ Center has been in the Learning Commons for over two full academic years. In the first year of the Learning Commons the Writers’ Center saw an overall increase of student usage of over 20% in comparison to the year before, when the Center was located on its own. At one point in its first quarter in the Commons, the Center saw over a 100% increase in student-contact hours in comparison to the same point in the previous fall quarter. The numbers did not stay this high, but the overall increase in usage—up 43% by the end of the first term—was still impressive.  The increased student usage in the first year in the Commons was not just a bump in usage because of novelty; student demand for the Writers’ Center has continued to rise since its move to the Commons. Overall, student usage of the Writers’ Center went up 58% in its second year in the Commons in comparison to its first.

The increased student usage in the first year in the Commons was not just a bump in usage because of novelty; student demand for the Writers’ Center has continued to rise since its move to the Commons. Overall, student usage of the Writers’ Center went up 58% in its second year in the Commons in comparison to its first.

Figure 7: The Writers’ Center’s area is in the middle of the Commons;

this location has required that the staff conduct class workshops in an open, shared area.

The relocation of the Center in the middle of an open learning space has also changed the way we interact with students as well as the range of students with which we interact. These changes have not only created challenges, but also may be serving to increase our ability to support an increasing number and a wider range of students. At our previous location, very few students outside of those who came specifically for one-on-one or group response sessions visited the Center. In the wide-open space of the Commons, we share our tables with many students who come to the Commons simply to study or work collaboratively with other students. That is, in the open space of the Commons, all of the tables are for general use; if a table isn’t occupied within the loosely demarcated area of the Writers’ Center, anyone can use it. Writers’ Center Responders and student writers find themselves working next to a wide and varied range of students, many of whom, we’ve observed, tend to be focusing on quantitative material. Our group sessions or even whole-class visits also occur in this wide-open, mixed use learning space. It may be that the increase in the Center’s usage has resulted not only from its increased visibility on campus, but also from the more diverse range of students who come to the Commons and find themselves studying and collaborating in the midst of the daily work of a writing center.

The move to an open, decentralized space has already begun to help the Writers’ Center challenge the narrative of marginalization common to writing centers, by disrupting the perception that such centers are spaces for remediation alone. The shared space of the Commons has resulted in the literal manifestation of the oft-repeated (and little-heard) message from writing centers to students and faculty that the space of the writing center is for everyone: strong writers and developing writers, those studying the humanities and those studying the sciences, should visit the writing center. The Writers’ Center space within the Learning Commons is now shared with every kind of student. Those who come to the Center to talk about writing are now working next to other students—from any number of disciplines and at every level of academic ability—who have come to the Commons of their own accord, to study alone or work collaboratively. By following this model, the sustainable learning space for the redesigned writing center can literally be a place where every manner of student and writer from across the disciplines comes to work, even if not every student is there to do the traditional work of writing centers. Further, this design also challenges the narrative of marginalization by ensuring that writing centers are not physically marginalized on the landscape of the university campus. While our Writers’ Center is not at the center of the Learning Commons, it now operates in the midst of a shared network of programs in a centralized campus location that pulls in students from across the campus and the curriculum. To illustrate how this approach and design came about, the story of the early development of the Learning Commons is told (on another page of this site) from the perspective of the administrators behind it, who were motivated and informed by what can be called a narrative of “student success.”

The move to the Learning Commons is not only an opportunity to challenge common misperceptions about the Writers’ Center as a place for remediation, but is also an opportunity to expand what we do, serving students by providing response to the range of communicative acts in which they engage, from the alphabetic to the multimodal. In short, the move to the Learning Commons is an opportunity to begin the Writers’ Center’s transformation into a multiliteracy center.

The Writers’ Center was developed with a strong foundation of traditional process-based writing center theory, taking as its theoretical underpinning that which Lisa Ede (1989) first suggested—the idea that writing is social act of knowledge construction. Its philosophy, then, is based upon dialogue and collaboration. A heavy degree of responsibility is put on writers themselves. They are responsible for their own writing, as the Writers’ Center Response session is collaborative, rather than directive. The move to the Learning Commons was an opportunity to revisit the Writers’ Center mission statement and goals. The Writers’ Center staff began this process by collaboratively choosing two standing goals for formal assessment and creating a new goal that reflects the Center’s ongoing transition toward becoming a multiliteracy center:

- Encourage writers to apply the strategies they develop during sessions at the Writers' Center across all disciplines and learning situations.

- Increase the ability of writers to assess, analyze, and develop their own writing and creative processes.

- Enable writers to understand and practice key principles of effective rhetoric in various media, and provide the opportunity for them to integrate writing with other forms of multimodal communication.

All of this isn’t to suggest that the transitional work described above was easy. In fact, much of it was difficult and at times painful. This work—which included the development of a new mission statement and student learning goals, an assessment plan, and an articulation of updated best practices for working with students in our relocated, re-visioned Writers’ Center—took up more than a year’s worth of weekly staff meetings. While most of our staff supported the location change, and the transformation of the practices and philosophies of the Center that this entailed, there were widely held fears about the possible negative impacts of the move. Further, in the case of a minority of staff members, there was outright resistance to the move and the changes it entailed, once it became clear that those changes would be significant. Once it became clear that the Writers’ Center would not be moving to the library to occupy its own unique space, there was general concern throughout the Center staff and leadership about the idea of sharing an open space with other programs, as well as concern about being identified with, or even subsumed by, programs that had traditionally been viewed as purely remedial. The most voracious resistance, from a few long-time staff members, came in reaction to efforts to revise our mission statement and goals, and particularly our efforts to develop a plan for assessing whether these goals were being met. It took over a year of hard, sometimes tense, collaborative work to get everyone on board with, and contributing, to the Center’s new direction. In that time, new staff members joined the Center, and others left, eventually resulting in an entire staff that approaches work in the Writers’ Center with an open, flexible mindset.

The center engaged in ongoing discussion and training to enable staff to continue to meet—or revise—the first two goals in the new environment of the Learning Commons, as well as develop new practices that will enable us to meet the third goal. The Assistant Director and I worked together to facilitate this discussion through specific reflective activities meant to help define (and redefine) what we do and why we do it. For example, we began one staff meeting by asking the staff to share stories of successful response sessions. We discussed specific practices that lead to effective one-on-one sessions; we also discussed how these practices would or would not transfer to sessions focused on multimodal texts. In another meeting, I asked the staff to reflect on and attempt to describe the attributes of the ideal EWU student writer, which led to an extensive discussion of our pedagogical practices and a renewed attempt to clarify/revise our original mission and goals for assessment which hadn’t been revised for over a decade. All of this work eventually led to the creation of a new Mission Statement, Goals, and Student Learning Outcomes.

Central to the collaborative discussion that the staff engaged in order to establish a re-visioned and revitalized Writers’ Center has been the incorporation of the new technologies we requested and added to our center in our new Learning Commons location, as well as our move to offer feedback on multimodal texts. The Writers’ Center staff has worked to respond to John Trimbur’s (2000) early discussion of the shifts in practice likely to occur as writing centers transition to multiliteracy centers:

To my mind, the new digital literacies will increasingly be incorporated into writing centers not just as sources of information or delivery systems for tutoring but as productive arts in their own right, and writing center work will, if anything, become more rhetorical in paying attention to the practices and effects of design in written and visual communication—more product oriented and perhaps less like the composing conferences of the process movement. (p. 30)

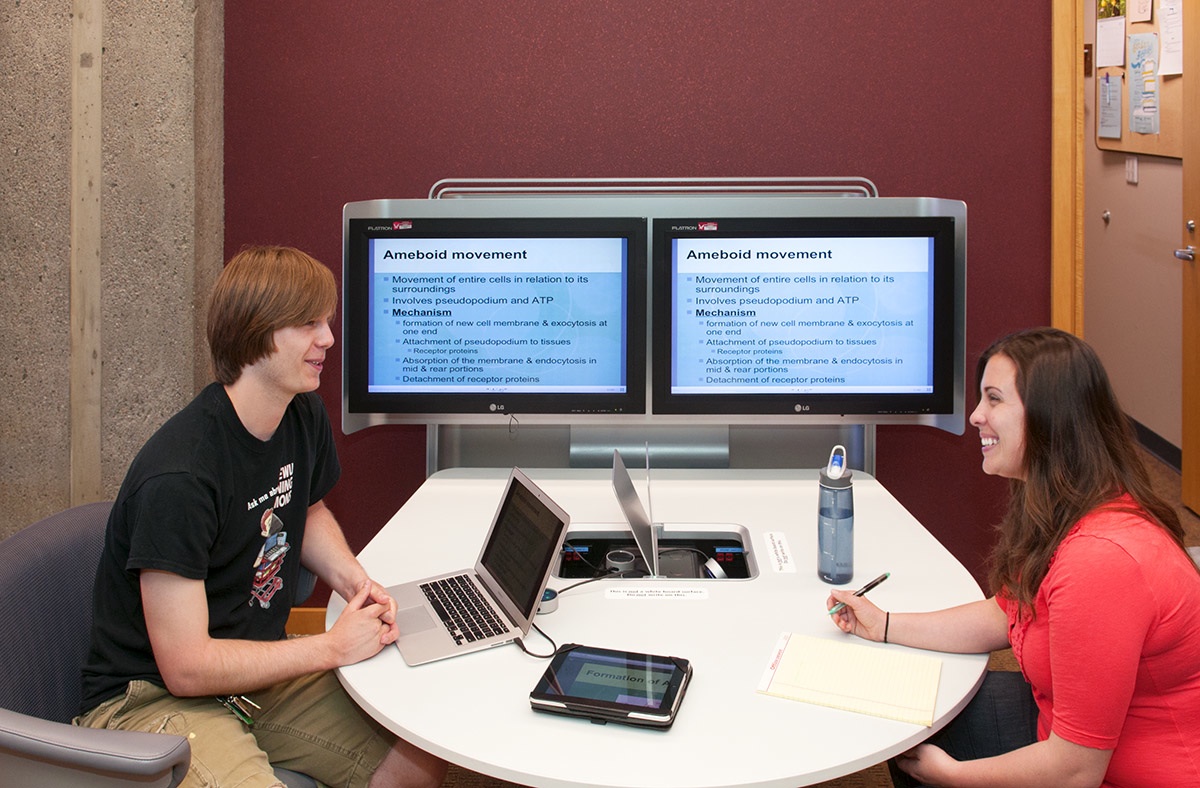

As our Center is strongly grounded in a philosophy of feedback that emerged out of the process movement, our challenge has been to adapt what we traditionally have done in writing-focused response sessions to new kinds of sessions that include technologies (now available in our new space) and multimodal texts. For example, the Writers’ Center zone of the Learning Commons now includes “collaboration stations,” where groups can display and compose texts using a range of devices (from laptops to tablets). Furthermore, Writers' Center staff discussion of practice now includes attention to how this technology might best be used to meet our learning goals in a manner consistent with our process-based philosophy. While Trimbur (2000) suggested that multiliteracy conferences may tend to be product-oriented, technologies like these collaboration stations enable students and staff to cooperatively engage in the process of text production in the space of the Center itself. Such examples suggest that our philosophy must be adapted to a space where the process of text production occurs more frequently. Similar Writers' Center staff discussions have focused on best practices for holding online Skype appointments in the Commons, for using the mobile technologies such as iPads now available to our staff, and even for incorporating the whiteboard tables around which we hold sessions.

As the Writers’ Center’s staff and administrators work to revise the center’s philosophy and practices, they have collaborated with the multi-media center (a program and space in the Learning Commons known as the Multi-Media Commons, or MMC) to determine how best to combine efforts and expertise to support the multimodal communication projects of students. (This collaborative effort will be discussed in greater detail in another section.) The move to a next-gen learning space, then, is not simply an opportunity to challenge flawed narratives about writing centers; it is also an opportunity to revisit standing goals, create new ones, and establish the innovative, collaborative practices that will (hopefully) lead to all of these goals—long-standing and brand new—being met.