The Swastika Monitor

The Swastika Monitor is an online swastika tracking project that is currently being designed with the help of Derek Mueller, associate professor at Virginia Tech. Currently, I should note, two other swastika tracking projects are publically accessible. The AMCHA Initiative has an ongoing swastika tracker, but it is only tracks anti-Jewish genocidal expressions that have occurred on college campuses in the United States since 2014 and does so in bullet list form. ProPublica also tracked anti-Semitic vandalism as part of their Documenting Hate project, but their data only accounts for incidents that occurred between November 2016 and February 2017. The Swastika Monitor will greatly enhance such open data efforts by offering not only an interactive digital map to identify the exact locations in which swastikas have surfaced since 2000 but also various infographics that will identify who is being targeted, in what local places swastikas are most surfacing and with what accompanying texts, and what individual and community responses are emerging. The Swastika Monitor will also make it possible for visitors to contribute to data collection by reporting encounters with swastikas and sharing their testimonies.

It is far too early in my research to draw conclusions from my data collection. However, I offer a sneak preview into The Swastika Monitor’s data visualizations and preliminary research findings so that you can gain a clear sense of what this project will entail and begin to develop insights based on presented data. Please understand that all visualization designs are tentative (designs will be solidified over the next few months).

Trigger Warning

WARNING: These visualizations contain representations of swastika-related incidents, which may trigger stress and trauma to some readers.

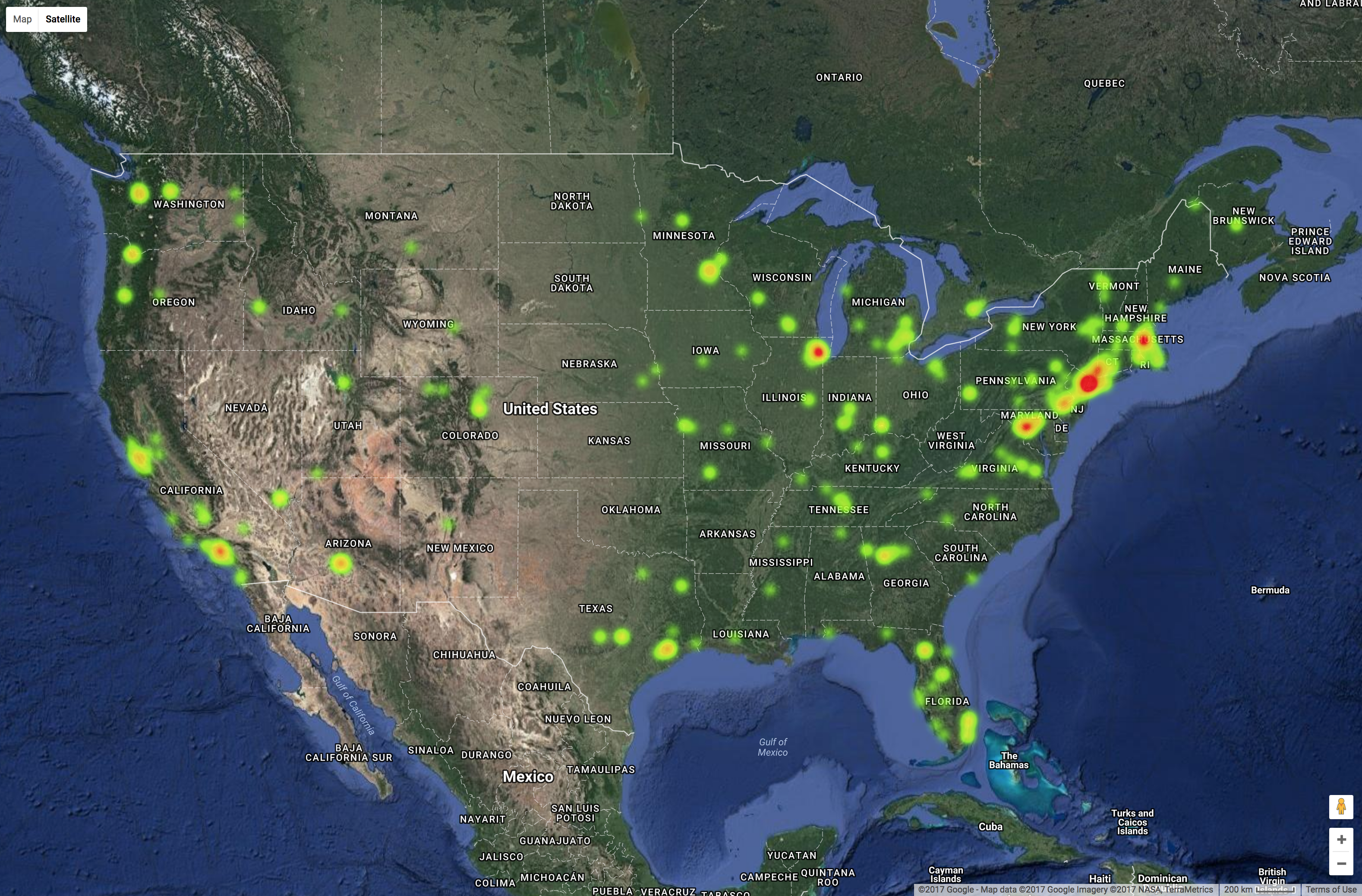

The data visualizations above indicate several things that ought to be of interest to rhetoric and writing scholars as well as the general public. Due to limited space, here I identify four. First, in Figure 2, we can see that swastikas have surfaced in nearly all 50 states, with most of the swastika incidents taking place in the Northeast. As a heat map indicates, hotspots of swastika incidents also surface around Chicago and in southern California (See Figure 3). More research into the targets of these incidents, as well as overlaying these maps with demographic data about race, ethnicity, religion, and political affiliation, may help develop deeper insights into why swastikas are emerging more in these particular hotspots rather than other places. With this geographical data alone, however, we can see that the emergence of swastikas is a national dilemma, unlike assumptions that may link visual rhetorics of hate with the South due to a longstanding history with explicit racism.

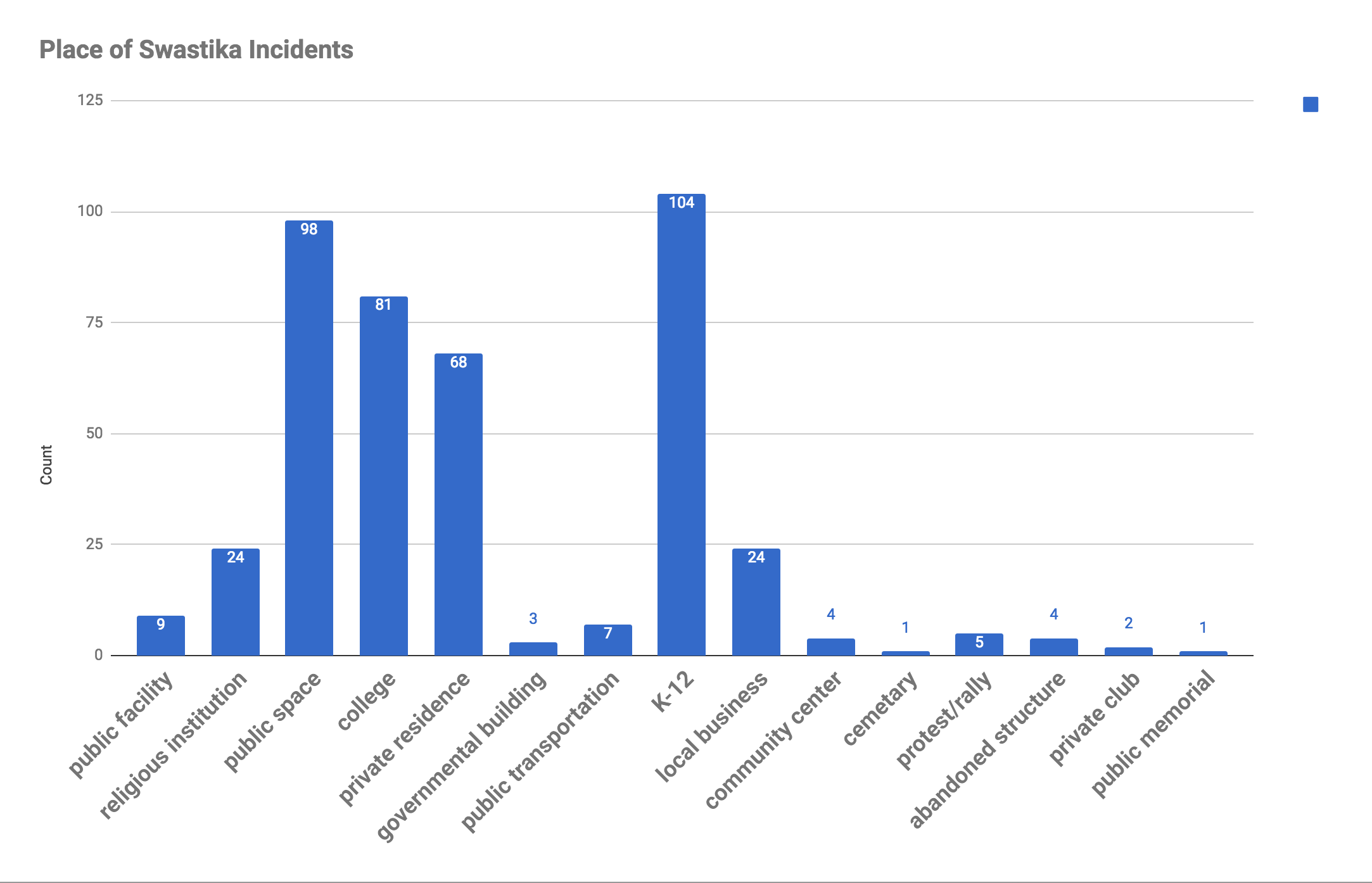

Second, as evident in Figure 4, as swastikas appear in various communities around the country, they are surfacing in all kinds of places—from educational institutions to governmental buildings to community centers to public spaces—and making serious threats to a wide range of marginalized peoples. Some targeted activity is, unfortunately, predictable. Considering the swastika’s unforgettable role in antisemitism, many might not be surprised to learn, for example, that Jewish institutions such as synagogues, Chabad houses, and cemeteries have been heavily targeted. Perhaps less expected, churches known in communities to be sanctuary spaces for immigrants and congregations open to diversity in terms of sexual orientation, ethnicity, and race are also being targeted. In addition, businesses known to support immigrant labor and/or owned by members of marginalized groups are being tagged with swastikas and other problematic slurs, such as when one eatery owned by a refugee from Iraq, now an American citizen, was tagged with "Rapeugees Shop Here." Also, as Figure 3 indicates, over 36 private residences—mostly belonging to minority individuals or families—have been tagged with swastikas. In one incident, a Muslim family found a note in their mailbox with the words “The KKK is coming for you, Muslims.” In another incident, the garage of an African American family was not only tagged with swastikas and racist slurs but also burned down. While we may expect swastikas to appear spray painted on urban walls, such frequency of residential targeting and violence is especially alarming, indicating how swastikas are circulating to threaten, to destruct, and to harm the lives of many diverse marginalized peoples.

Third, as educators, we ought to also find alarming that, as evident in Figure 4, swastikas are most frequently surfacing in educational spaces. While the AMCHA initiative is doing a remarkable job keeping tracking of swastika incidents taking place at colleges around the country, my research indicates that K–12 institutions are being heavily targeted as well. Many of these swastikas are surfacing in school bathrooms, indicating that students are likely the culprit. After the 2016 presidential election, SPLC put out a report responding to what they called the “Trump Effect,” resulting in increasing incidents of hate and anxiety in K–12 settings. Whether we agree with the extent to which Trump’s discourse is responsible for such incidents, as rhetoricians, we might make strides toward working more closely and intently with K–12 institutions to develop writing education that not only addresses rhetorics of hate and the complexities of oppression but also offers “training in civic discourse that has intellectual integrity but also practical effectivity and moral attracting” (Fleming 94).

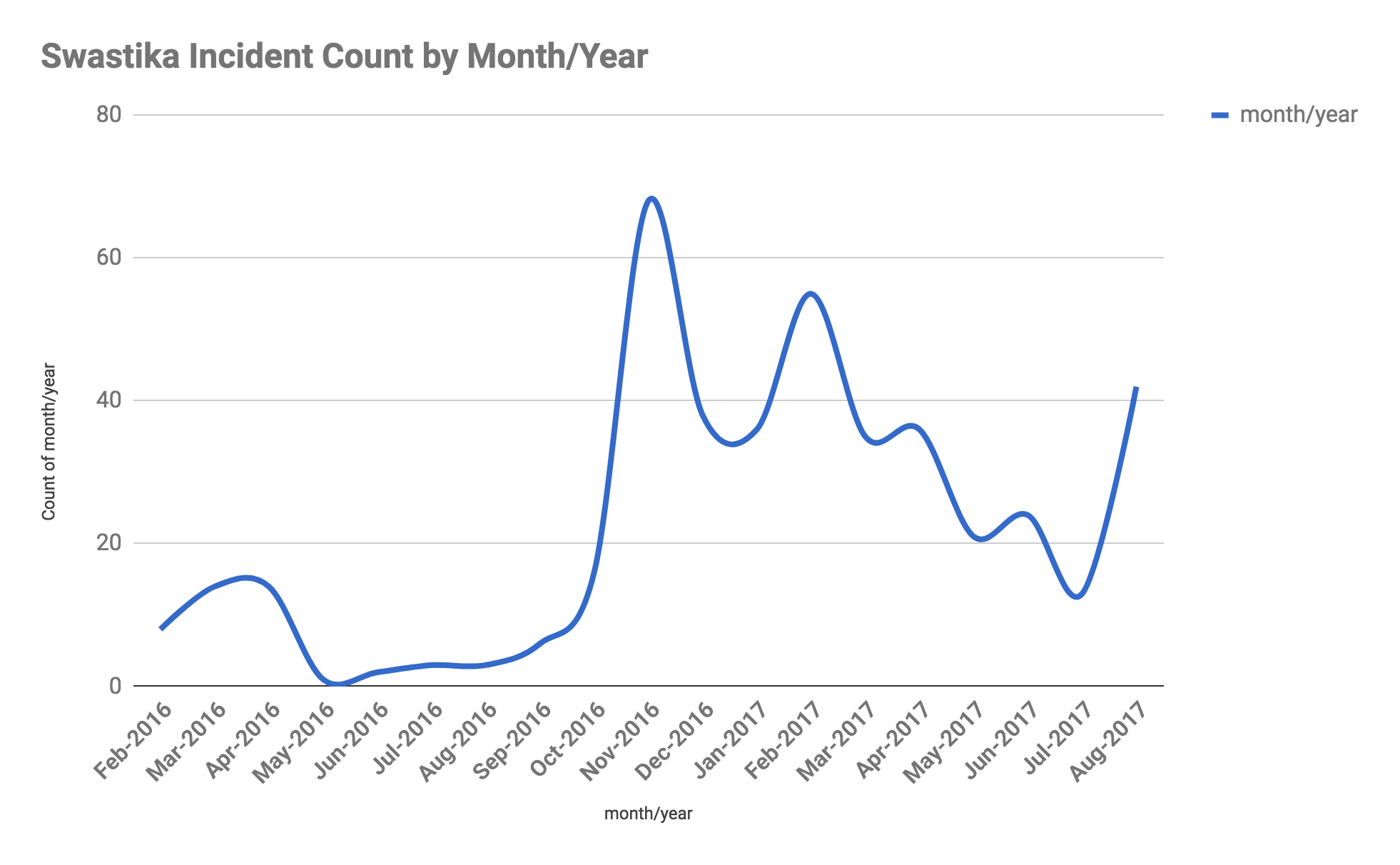

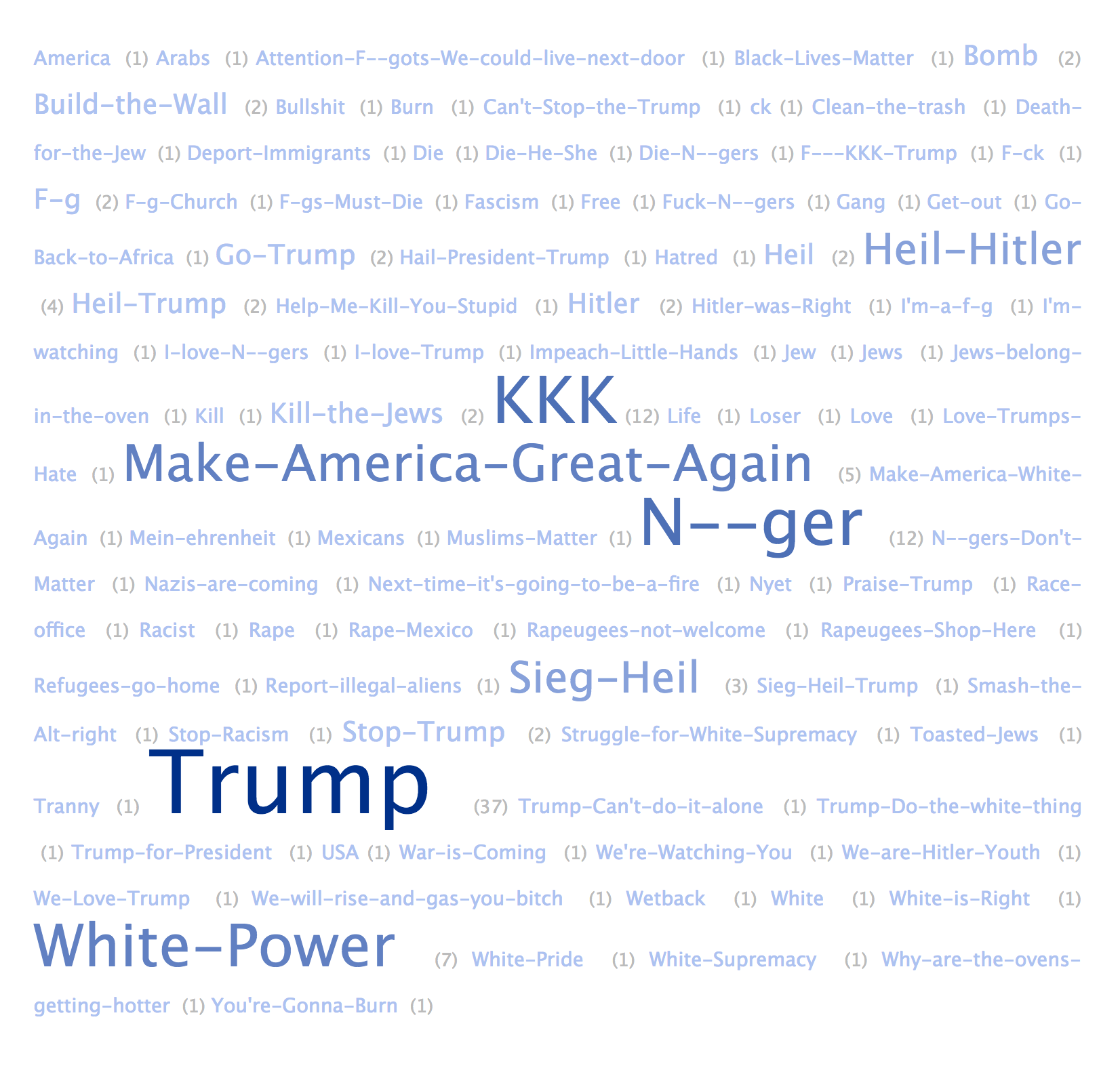

Fourth, Figure 5 indicates that many swastikas are surfacing in relation to Trump, white nationalism, and/or white supremacy. As the word cloud makes evident, Trump is the most common text that accompanies swastikas across the nation with his slogan “Make America Great Again” closely behind. In many cases, the association with Trump is fairly clear, depending on the accompanying words and/or location in which a swastika emerges. In other cases, it is admittedly difficult to ascertain whether such rhetoric is pro-Trump or anti-Trump; more research is needed to tease out this relation. But we can claim with certainty that Trump is a trigger for swastika production, as indicated here in Figure 5 by a spike in swastika production that occurs around both the election of Trump in November of 2016 and just after his inauguration during January and February of 2017.

In addition, Figure 5 indicates that multiple references to white supremacy accompany the swastika. Interestingly, recent journalism reports that groups such as the White National Socialist Movement are abandoning the swastika as a branding device (Kovaleski et al). “Indeed,” as Rick Hampson writes in a report about the Charlottesville rally, “most of the neo-Nazis and white supremacists who helped turn Jefferson’s town into a battleground used other symbols, from the Confederate battle flag to the Detroit Red Wings logo.” However, as evident in photographs taken at recent KKK rallies and in fliers produced by neo-nazi groups such as The Atomowaffen Division, some groups still look to the swastika to promote their ideas and to recruit. And as indicated by the prevalence of “White Power,” “KKK,” and various instantiations of racist and Nazi rhetoric that appear alongside the swastika in private and public spaces across America, the swastika maintains its vitriolic popularity among those aiming to shock, insult, harm, and intimidate. The swastika thus still obviously remains deeply connected to pro-white sentiments, maintaining, in Raymond Williams terms, its residual role as an emboldened expression of racism and anti-semitism in the United States. Whether functioning to demarcate white people’s racial superiority, claim cultural and political power based on ethnicity in the United States, threaten people’s lives, or simply instigate fear and shock, the swastika raises serious concerns about our contemporary racial and political landscape and its socio-material repercussions.