Producing Truth

There is a danger to any conversation focused on how the “truth” is produced.

There is also a danger in our overestimations of our ability, our actual power, as individuals and as a discipline, to create a progressive inclusive “truth” in response to recent national and international events.

I say this because over the past several years, I have been witness to individuals in Syria who have had their truths, their collective ethical values, tortured, gassed, and bombed until the very streets on which those aspirations emerged no longer exist.

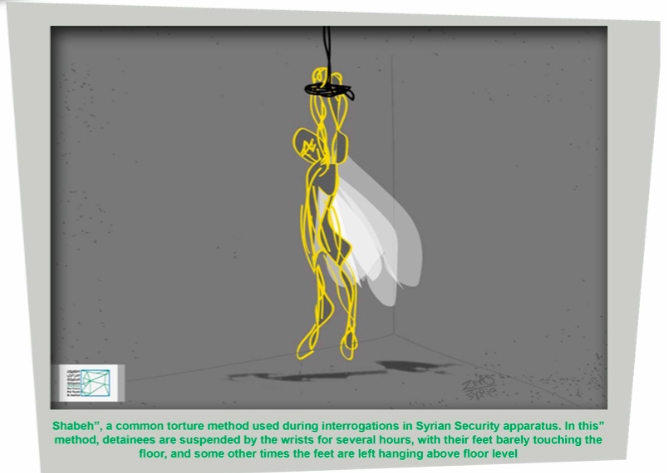

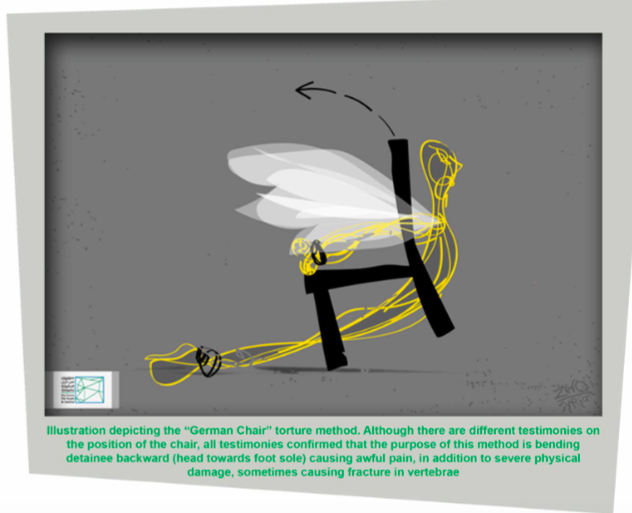

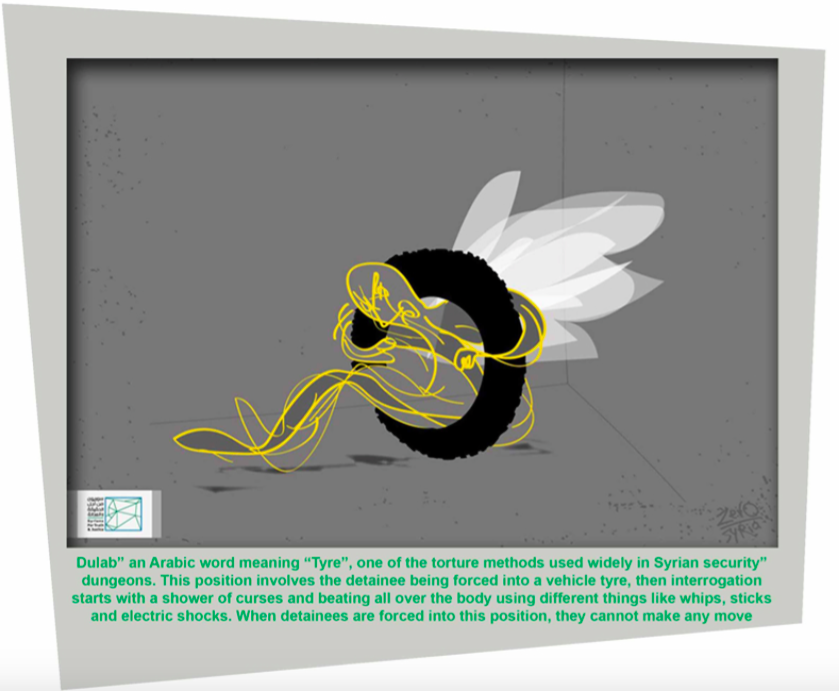

With some of these very individuals, I have been part of a collective attempt to confirm this harsh reality. We have documented chemical bombings in Syria that are deliberately timed to inflict pain onto families in local markets. We have recorded the stories of prisoners so closely packed into a prison cell that their sweat formed condensation that rained down on them. We have proven the existence of prison cells deliberately located near the very rooms where torture occurred and where resulting dead bodies were stacked.

Throughout, we have tried to escape the rhetorical box which reduces these individuals to the sum of their torture by projecting the agency of those who still live in their neighborhoods (See Hesford). We have attempted to demonstrate the collective attempt by these individuals to build a future for their families, their neighbors, and their land based upon local values of tolerance and rights. Organized as Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ), we have tried to attach our work to other efforts dedicated to producing a new configuration of moral and political apparatuses that might enable a different constellation of truth upon which to build a more just future.

Throughout, I have tried to articulate the conceptual, programmatic, and institutional contexts in which my professional identity exists into these efforts. I have tried to understand how the history of my field, as now embedded across a range of concepts—such as public rhetoric, community partnership, social justice—might allow new possibilities of alliance and effort between myself and Syrian activists. I have tried, that is, to understand how our overlapping waves of effort could be formed into a structural intervention.

Yet, I have often been asked whether such work can honestly be described as within our field: “Isn’t it really just activism?” Indeed, as the field moves aggressively to produce its own truth—through concepts such as writing about writing; through expanding apparatuses such as graduate programs and undergraduate majors—this is not simply a rhetorical question. Indeed, as the “we” of our field continues to consolidate, this same “we” needs to consider whose identities, heritages, knowledges, and world views are being actively excluded from our concern. This same “we” needs to consider what is lost when certain projects seem to fall outside of the true work of our field by being considered “primarily activism.” And there is a need to be concerned when our field cuts itself off from the political firmament and actions which led to its disciplinary status today, even in the name of seemingly productive possibilities.

Using the creation of STJ, I want to offer an example of how existing within the complexity of a moment and working within the differing subject positions being offered by disparate institutions and conceptual frameworks, it is possible to build new institutional mechanisms dedicated to the enactment of an inclusive vision of truth and human rights. And in doing so, I want to argue that we are better off as a field deeply committed to the humbling work of producing important ‘truths,’ than cutting our ethical conscience to open up disciplinary possibilities within a university structure which has historically cared neither for our students or our labor.

Written by Steve Parks.