Conclusion

Histories are imperfect documents. They are inevitably partial and biased. And as Hawisher et al. (1996) put it in the Afterword of The History Book, “History [...] could never be as full and rich as life” (p. 280). This history of computers and writing from 1995–2015 is no different. Despite their limits, however, histories provide invaluable documentation and insight into the subject of study. We hope our history of computers and writing in this eBook has done just that, offering a portrait of the development of the (sub)field over a twenty-one year period, a time of unprecedented growth and change in writing technologies, following Hawisher et al.’s (1996) Computers and the Teaching of Writing in American Higher Education, 1979–1994.

In Chapter 1 this eBook argues that, during the period under review, the (sub)field embraced the visual and social turns, adopting a capacious definition of writing that included multiple modes and media. Its practitioners analyzed and produced texts in various forms, pushing the boundaries of what texts can be and do.

Chapter 2 evidences that the (sub)field likewise embraced an expansive definition of computer, with its members studying (and even creating) a range of digital communication technologies, from online writing labs and online writing instruction to wikis and MOOCs (massive online open courses). We found scholarship on each of these technologies followed an identifiable pattern: initial celebration and belief that the technology would democratize communication and education, critique of the shortcomings of the technology in achieving this goal, and finally attention to ways in which students and teachers actually use the technology and suggestions for ways best to use it for communicating and learning despite its shortcomings. Overall, though, Chapter 2 points to the ways in which the (sub)field of computers and writing has been consistent and rigorous in its critical attention to technologies and in its attempts to temper techno-utopianist points of view.

Chapter 3 shares findings from a distant reading of programs from the (sub)field’s flagship conference, Computers and Writing. In addition to offering data to support the (sub)field’s broad notion of the forms of writing and digital technologies under its purview, this chapter points to sustained and new interests in the (sub)field. Machine reading of keyword frequency supports that attention to both pedagogy and theory were persistent during the period under review, as were considerations of the cultural aspects of composing. More recent interests included disability studies, play, video games, and coding.

Chapter 4 turns attention to another of these newer interests, the digital humanities (DH). It contends that the (sub)field’s relationship with DH is bound up in its own tension between process and product, especially as writing studies, computers and writing’s parent field, most visibly aligns with process and DH most visibly aligns with product. The chapter identifies three main responses to DH within the (sub)field, indignance at DH, embrace of DH, and rejection of DH, while also calling attention to more nuanced views of DH vis-à-vis computers and writing. One way our history may be useful is to apply awareness of the arc of scholarship about new technologies that we identify in Chapter 2 (i.e., initial celebration followed by critique and ultimate acceptance of the technology’s enduring presence and how best to use it) to the (sub)field’s relationship with DH. While DH’s initial shine may have dimmed, it has endured and will likely remain an influential force within higher education into the future. Thus, computers and writing teacher-scholars may do well to position themselves vis-à-vis this more visible technology-focused field within the humanities, even if they ultimately decide not to call themselves digital humanists.

For the remainder of this Conclusion, we turn to the question in the title of our eBook: Are we “there” yet? We ask this question in response to a 2004 Computers and Composition article, “Re: The Future of Computers and Writing: A Multivocal Textumentary,” which opened with the following resolution from contributor Steven D. Krause:

Resolved: In the near future, the field/interest/sub-discipline of computers and writing will cease to be different from the field/interest/larger discipline composition and rhetoric because all composition specialists shall be expected to understand the importance of using computers and other technologies to teach writing. (Hart-Davidson & Krause et al., p. 147).

There are two parts to this resolution: 1) the idea that computers and writing and writing studies will become one unified academic field and 2) the idea that all writing studies specialists will understand the importance of computers (and other technologies) for the teaching of writing. Both parts are still debated/debatable.

In their “Looking Forward” chapter at the conclusion of The History Book, Hawisher et al. (1996) discussed the “changing visions of school-based writing and learning” (p. 244). In doing so they referred to a few books and articles that did this kind of future-oriented imagining. For example, in regard to computer-mediated communication (CMC) “evolving into a new genre” (Hawisher, et al. p. 244), they cited Paul Taylor (1992), who wrote, “[W]e must [...] be prepared to reevaluate our old assumptions about how texts communicate. Otherwise, we will simply become the old guard that, according to Thomas Kuhn, will literally have to die off while the winds of change sweep past us” (p. 146). While it is fair to say that the majority of those who teach writing have accepted the computer as a crucial writing tool, as we show in Chapter 2, there is still disagreement about what counts as “writing.” Arguably, there still exists an “old guard” (mostly outside of computers and writing) that does not see the kinds of writing platforms that CMC evolved into as productive forms of communication or as important, useful for, or even relevant to writing pedagogy.

In relation to Krause’s (2004) resolution, then, this Conclusion answers two questions: 1) To what extent has computers and writing cohered as its own autonomous (sub)field? and 2) What is the (sub)field’s relationship to writing studies more broadly? To answer these questions, we reflect back on the twenty-one years worth of materials we gathered, read, and studied in the course of writing this eBook. Additionally, we reflect on the closing chapters of The History Book, in which the authors both described their current historical moment (1994) and offered some predictions for the future of the (sub)field.

Page 1

Yes, Computers and Writing Is an Autonomous (Sub)Field

One way to answer the question of whether computers and writing has cohered as its own autonomous (sub)field is to consider computers and writing’s visibility and recognition within academia. Much data supports that computers and writing has met common requirements for (sub)disciplinary status. For instance, it has several well-read peer-reviewed academic journals, including those we studied for this history. These journals are established, having now published for decades. Computers and Composition began as a newsletter in 1983 and then a journal in 1985, ten years before the period under review in this history. Computers and Composition Online and Kairos both started publishing in 1996, just after our history begins. Neither existed at the time Hawisher et al. wrote The History Book. At the time of this writing, the Computers and Composition blog reported that the journal was downloaded in 64 countries (“Brief,” n.d.), and on its website Kairos boasted 45,000 readers per month, including 4,000 internationally (“What is Kairos,” n.d.). Computers and Composition, Computers and Composition Online, and Kairos were all indexed by the MLA (Modern Language Association) International Bibliography, and Computers and Composition articles were accessible via the ScienceDirect database.

In addition to having longstanding academic journals, the (sub)field has met other criteria for disciplinary status as well. Computers and writing has an annual national conference, Computers and Writing, that attracts several hundred presenters each year. We analyze programs from this conference in Chapter 3. And while not a standard criterion for disciplinary recognition, at the time of this writing computers and writing had its own Wikipedia page, which discussed both the (sub)field and the conference. Computers and writing also had PhD programs—or at least PhD students in writing studies could specialize in computers and writing (RhetMap listed 94 North American doctoral programs in writing studies as of August 2019).

Additionally, the academic job market recognized computers and writing. Since 2013–2014, “technology and digital media” has been its own academic field category on the MLA Job Information List (JIL), alongside other well-known subfields like American literature, British literature, film and media studies, linguistics, and women’s and gender studies. While jobs with a focus on technology and digital media existed for some time prior to this designation, the creation of a specific MLA job category, able to be filtered by job seekers, represents an acknowledgment of these jobs by English studies’ primary organizing body. For instance, of the 1,575 postings in the JIL in 2014–2015, the end of the period of our history, 135 (8.6 percent) were in technology and digital media (MLA Office, 2015, p. 25). (This category, of course, included more than computers and writing positions; it was also used for digital humanities positions. But these positions were likewise pertinent to and of potential interest to computers and writing specialists.)

Page 2

No, Computers and Writing Is Not an Autonomous (Sub)Field

Other data, however, challenge that computers and writing has achieved (sub)disciplinary autonomy—or at least recognition. To return to the MLA JIL, the number of jobs tagged as “technology and digital media” declined from 143 jobs in 2013–2014 to 93 jobs in 2016–2017 (MLA Office, 2017, p. 30). This decline, of course, is consistent with an overall decline in job postings during this period; the number of postings for writing studies positions as a whole likewise declined (from 295 to 217 postings) (MLA Office, 2017, p. 29). Yet this decline potentially supports that computers and writing is not a robust (sub)field.

Additionally, Chapter 4 of this eBook illustrates that digital humanities (DH) is more widely recognized and financially lucrative than computers and writing both inside and outside academia. As we discuss in Chapter 4, DH scholarship rarely includes the voices of computers and writing scholars, despite the belief of several computers and writing scholars that they have been doing DH work for decades.

Classification of Instructional Program (CIP) codes perhaps offer the most persuasive evidence that computers and writing has yet to achieve (sub)disciplinary visibility and autonomy. CIP codes, instituted by the National Center for Education Statistics arm of the U.S. Department of Education, provide a “taxonomic scheme” that allows for tracking academic program completion in institutions of higher education in the United States (“What Is the CIP,” n.d.). Approximately 7,500 colleges, universities, community colleges, and vocational schools use six-digit CIP codes when completing the IPEDS (Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System) Completion Survey. IPEDS collects data on everything from student enrollments, program completion, and graduation rates to tuition expenses and financial aid awarded. The program completion portion of the survey requires use of CIP codes. Once these data are gathered, groups, including parents and students, Congress, federal agencies, state governments, and the military, as well as professional organizations, businesses, and hiring firms “that need to recruit individuals with particular skills,” use the IPEDS survey data “extensively” (IPEDS, n.d.).

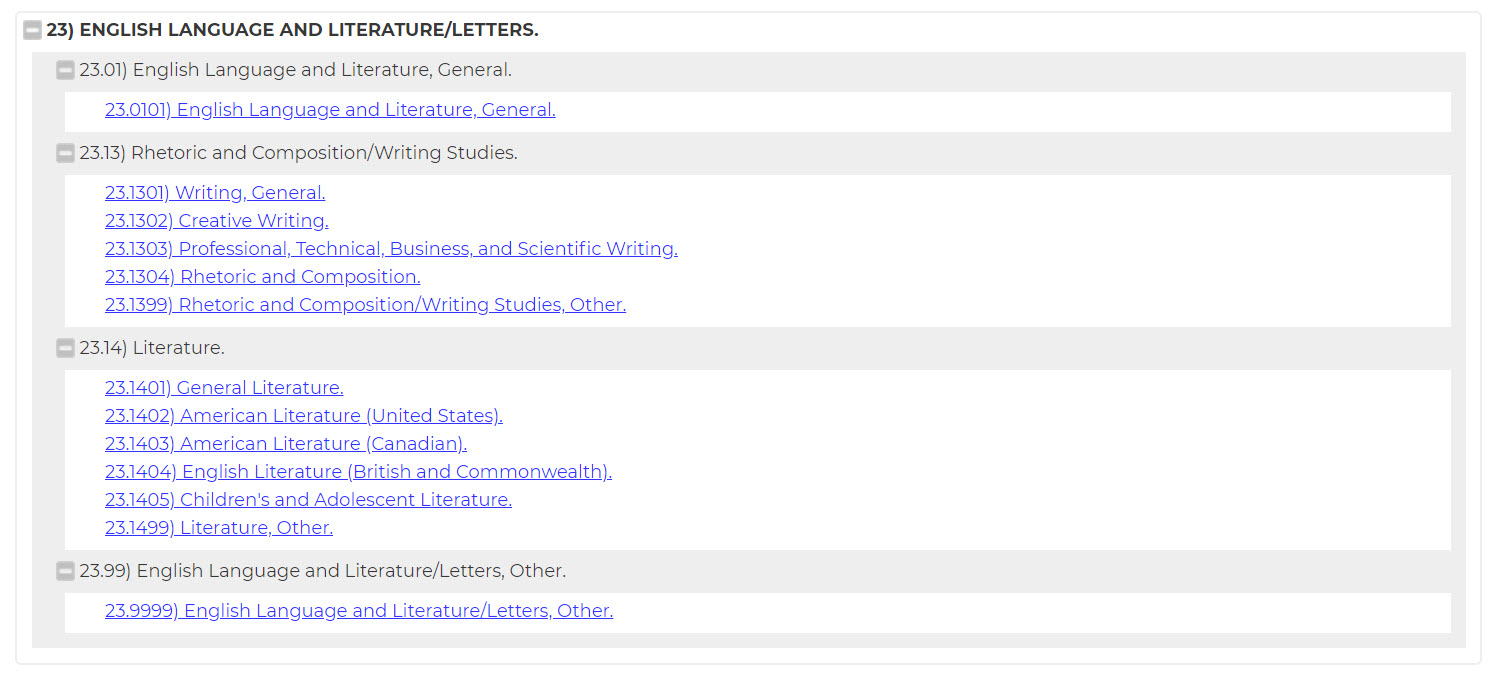

Throughout the period under review and at the time of this writing, “computers and writing” did not have a CIP code. As a result, it was to some extent invisible as an area of study to employers, the government, and, perhaps most important, to students. As shown in Figure 5.1, which lists CIP codes under the parent category of “English Language and Literature/Letters,” “Rhetoric and Composition/Writing Studies” did have a CIP code, as did other subfields of writing studies, including “Professional, Technical, Business, and Scientific Writing.”

Figure 5.1: CIP Codes for English Language and Literature/Letters (“Detail for CIP code 23,” n.d.)

The CIP codes did not ignore computers and writing, however. Description of the “Writing, General” classification, for instance, mentioned “writing technologies” and included concerns of computers and writing:

instruction in writing and document design in multiple genres, modes, and media; writing technologies; research, evaluation, and use of information; editing and publishing; theories and processes of composing; rhetorical theories, traditions, and analysis; communication across audiences, contexts, and cultures; and practical applications for professional, technical, organizational, academic, and public settings. ("Detail for CIP code 23.1391," n.d., emphasis added)

“Professional, Technical, Business, and Scientific Writing”’s description, particularly the final section, similarly included elements characteristic of computers and writing:

A program that focuses on professional, technical, business, and scientific writing; and that prepares individuals for academic positions or for professional careers as writers, editors, researchers, and related careers in business, government, non-profits, and the professions. Includes instruction in theories of rhetoric, writing, and digital literacy; document design, production, and management; visual rhetoric and multimedia composition; documentation development; usability testing; web writing; and publishing in print and electronic media. ("Detail for CIP code 23.1303," n.d., emphasis added)

Despite these gestures, study in computers and writing would need to be classified formally either as “Writing, General” or “Rhetoric and Composition/Writing Studies, Other” for the IPEDS. Neither situates computers and writing as a distinct (sub)field. As a result of this lack of separate CIP code, completion of computers and writing coursework or programs is not tracked in the same way as other subfields of writing studies (and English studies more broadly). Said another way, the U.S. Department of Education has yet to see computers and writing as prominent or distinctive enough to necessitate its own category for data gathering.

Yet the diffusion of issues of concern to computers and writing across these CIP code categories might be read differently. Its appearance in multiple descriptions under “English Language and Literature/Letters” might be seen as supporting that computers and writing has infused writing studies as a whole. In other words, writing studies writ large has taken up issues that used to concern only computers and writing specialists, so computers and writing need not be treated as a separate (sub)field. This reading is in keeping with the premise of Hart-Davidson and Krause et al.’s (2004) article—computers and writing could one day be conflated with writing studies—the premise upon which this chapter is predicated. We discuss computers and writing’s relationship with writing studies further in the next section.

Another challenge to the notion that computers and writing is “there” in terms of achieving status as an autonomous (sub)field is the dearth of undergraduate programs in computers and writing in U.S. institutions of higher education (which, of course, contributes to its lack of CIP code). By and large, undergraduate students as of yet cannot major or minor in computers and writing. Thus, for most undergraduate students, their only exposure to computers and writing as a (sub)field, if at all, is in first-year writing courses taught by computers and writing specialists or in undergraduate writing and rhetoric or professional and technical writing/communication programs. During the period under review, the latter programs were offered at institutions with graduate programs in writing studies that included computers and writing faculty (e.g., James Madison, Purdue, Wayne State). Certainly individual undergraduate computers and writing courses were developed between 1995–2015. For instance, Jeremiah Dyehouse, Michael Pennell, and Linda K. Shamoon (2009) discussed the creation of such a course, Writing in Electronic Environments, for their undergraduate major in writing and rhetoric at the University of Rhode Island, one of the relatively few such undergraduate majors in the U.S. during our history.

This lack of undergraduate curriculum programming is, of course, an issue for the larger discipline of writing studies as well. The challenges of creating writing and rhetoric/writing studies undergraduate majors have been well chronicled (e.g., Estrem et al., 2007; Giberson & Moriarty, 2019; Giberson, Nugent, & Ostergaard, 2015; O’Neill, Crow, & Burton, 2002; Shamoon, Howard, Jamieson, & Schwegler, 2000). English majors by default focus on literature/literary studies. They lack awareness of writing studies, let alone computers and writing, as a field of study under the umbrella of English studies. This awareness comes later, if at all. Chris Burnham recounted a familiar origin story for compositionists in his co-authored chapter in A Guide to Composition Pedagogies: he was “trained as a literary critic” and later came to develop an interest in writing studies (Burnham & Powell, 2014, p. 112). Chris M. Anson (2014) shared a similar story in his chapter in the same volume: he was introduced to writing studies through being assigned to teach first-year writing as a graduate student pursuing an M.A. in creative writing (p. 212). Perhaps the future will bring documentation of similar stories from computers and writing specialists who came to learn about computers and writing while pursuing degrees in writing studies.

Public understanding of computers and writing likewise challenges that it has achieved larger recognition. Outside academia, computers and writing specialists are rarely consulted by media organizations as experts regarding writing technologies, production, or instruction. And certainly those of us who are members of the (sub)field have had the challenging task of explaining not only to family members and friends but also to fellow academics what the (sub)field of computers and writing is, particularly as the (sub)field’s frequent association with English departments usually translates to perception that its practitioners study literature. This confusion is also shaped by the fact that most people think of computers as “natural” tools for writing, a belief consistently challenged by teacher-scholars in the (sub)field, as we note in Chapter 2. This same belief brings us to a discussion of computers and writing’s relationship with its parent field of writing studies. If computers are now the dominant tool for writing—a dominance now more pronounced than at the (sub)field’s inception—what continued need do we have for scholars who study technologies of writing?

Page 3

Computers and Writing’s Relationship with Writing Studies

Another way to measure computers and writing’s success (or lack thereof) in achieving (sub)disciplinary autonomy is to consider its relationship with its parent field of writing studies. In their introduction to The History Book, Hawisher et al. (1996) described computers and composition as both a “research community” and “a community of teachers” (p. 1). In her Preface to the book, Lisa Gerrard characterized it as “a series of experiments within composition” that, at the time of her writing, led to “a coherent subdiscipline with its own identity” (p. xii).

In the 2004 Computers and Composition article “Re: The Future of Computers and Writing: A Multivocal Textumentary” (Hart-Davidson & Krause et al.) that we reference to open this chapter, contributors considered—and debated—computers and writing’s relationship with writing studies. Nick Carbone, for instance, argued that computers and writing would remain “for now” (in 2004) “such as it is: a small off-shoot that we entered via composition” (p. 149). Johndan Eilola-Johnson added,

the inclusion of the term “writing” in computers and writing rather than “communication” strikes me as part of the problem. Communicating with/across/within a computer is no longer about writing as a primary activity—even though we’re often largely locked into it—but about design in the broadest sense of the term: not just graphic design or visual design, but architecture, product design, video, audio, and more. That’s not to say that there might not continue to be a field of computers and writing, but I think that field will continue to be an increasingly small subset of composition and rhetoric.” (pp. 156–157)

Johnson-Eilola’s contention regarding design has borne out to some extent. Chapter 3 shows that the term design* has been used in every conference program since Johnson-Eilola made this prediction in 2004; however, its use has not steadily increased. That is, it is not clear that there has been more attention to design in the (sub)field, though it has been consistent.

Rather than see computers and writing as a “small subset of composition and rhetoric,” Krause (2004) affirmed that the distinction between computers and writing and writing studies “is largely over” and that this conflation should be celebrated. In the article he went so far as to hum to the tune of REM, “It’s the end of computers and writing as we know it (and I feel fine)” (p. 152).

As we address in the Introduction to this eBook, The History Book explored the question of whether computers and writing is a separate field from or subfield of the larger field of writing studies. While the primary inspiration for this eBook came from that early landmark book, another inspiration was some of the premises and predictions in the multivocal 2004 Computers and Composition article “Re: The Future of Computers and Writing: A Multivocal Textumentary” about the future relationship between writing studies and computers and writing. The video below explores that relationship as it stands in the minds of these teacher-scholars at the time of their interviews. It also highlights ways in which computers and writing continues to be distinct from the parent field of writing studies.

Download a PDF transcript of this video.

One year after Hart-Davidson and Krause et al.’s future-looking 2004 article, in 2005, at the halfway point of the period under review in this history, the WIDE (Writing in Digital Environments) Research Center Collective at Michigan State University likewise addressed the place of computers and writing in writing studies. In “Why Teach Digital Writing?”, collective members Bill Hart-Davidson, Ellen Cushman, Jeff Grabill, Dànielle Nicole DeVoss, and Jim Porter (2005) argued that computers and writing would—or “should”—come to be central to, even indistinguishable from, the field of writing studies:

Here is the more disturbing implication of what the field of computers and writing has been doing for 20 years; that field has been assigned to a secondary status as a subfield in rhetoric and composition, a specialty area which, while important, is secondary to the main field. What happens if, in effect, computers and writing becomes the main field? What happens if that is the field of composition in the 21st century (Bill Hart-Davidson & Steven Krause, 2004)? Our article explores the implications of this point and argues the case that indeed this will happen, or should. (“Introduction”)

WIDE Collective members rejected the “secondary status” of computers and writing, largely because they affirmed that “[w]riting instruction MUST be computer based, in some sense, to meet the needs of student writers” (“Introduction”). They elaborated,

The degree to which we are willing to [live up to our shared conception of writing, our rhetorical view] may well determine the biggest difference between those who believe teaching digital writing to be a central as opposed to a specialized practice. To put it bluntly, we argue that computers and writing specialists routinely consider more of the classical rhetorical canon—invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery—than mainstream compositionists do. They also routinely invite more real-world practice into their writing classrooms via technology across all of the canonical categories. (“Rhetorical”)

In other words, they professed that computers and writing specialists more fully capture the breadth of writing and rhetoric (because they consider all five rhetorical canons) than do writing studies teacher-scholars who are not computers and writing specialists. From this perspective, it is impossible truly to be a writing studies teacher-scholar without being a computers and writing specialist.

Similarly, Collin Brooke (2009) presented new media as intrinsically rhetorical in his book Lingua Fracta: Towards a Rhetoric of New Media. Brooke sought to offer new rhetorical canons updated to reflect work in computers and writing. He characterized existing “canonical” rhetorical scholarship in computers and writing (e.g., Welch, 1999; DeWitt, 2002) as descriptive, that is, as showing the relevance of existing theories of classical rhetoric as opposed to devising new ones, or treating rhetoric in a reductive, limited way (e.g., Landow, 1997). To fill this gap, he outlined a new theory of rhetoric for technology, one that built on but was not limited to the canons of classical rhetoric, one that sought to restore the “dialectical” character of the canons (p. xiii). He devoted a chapter to each of the canons of rhetoric and framed them not as steps in a process of writing but rather as sites within a broader “rhetorical ecology” of writing (p. xii). He offered an updated alternative to each classical canon:

- Invention: Proairesis

- Arrangement: Pattern

- Style: Perspective

- Memory: Persistence

- Delivery: Performance

Ultimately, he professed wanting a rhetoric that is “actionary” not reactionary—in other words, a means of future production rather than an analytic to describe previous products (p. 22). This project to update the canons depended upon the traditional rhetorical canons being a focal concern for the field of writing studies.

Not all discussions of the relationship between writing studies and computers and writing have been as polemical as The WIDE Collective’s “Why Teach Digital Writing” (Hart-Davidson et al., 2005) or as thoroughly developed as Brooke’s (2009) Lingua Fracta. Yet concern over disciplinary identity has led writing studies teacher-scholars to anticipate the future. In 2011, for instance, members of the (sub)field again took on the task of prognosticating. Though focused less directly on the (future) place of computers and writing vis-à-vis writing studies, contributors to “Computers and Composition 20/20: A Conversation Piece, Or What Some Very Smart People Have to Say about the Future” (Walker et al.) extended a Town Hall at the 2011 Computers and Writing Conference to envision the future of “the field loosely termed computers and composition” (p. 327).

In his contribution to the article, Douglas Eyman tackled the question that serves as the basis for Chapter 1 of this eBook: “What is writing?” His contention echoed our findings from Chapter 1: in computers and writing “writing serves as a means to design a rhetorical act of communication, and this work of designing the rhetorical act can utilize a broad range of semiotic resources, not just printed text.” For Eyman, this broad definition of writing also led to concomitant questions of where writing happens and what writing does (Walker et al., 2011, pp. 329–330). He went on,

If we take such a broad view of what writing is, then our pedagogical approaches can take into account new forms of writing, including texts, tweets, blog postings, podcasts, video arguments, multimedia and multimodal works that frame interaction as a form of reading, and new forms that we have yet to encounter or imagine. (Walker et al., 2011, p. 329)

If the (sub)field’s history is any indication, Eyman’s point—that writing references more than printed text and that it occurs across a range of technologies and spaces—will continue to remain true for the (sub)field.

Four years later, Eyman (2015) positioned his book Digital Rhetoric: Theory, Method, Practice in relation to writing studies (as well as to other fields). In fact, Eyman explicitly aligned with Brooke (2009) and The WIDE Collective (2005) regarding the need to rethink the classical canons of rhetoric in defining digital rhetoric as a field of study (pp. 62, 64). The first chapter of Eyman’s book, titled “Defining and Locating Digital Rhetoric,” explicitly sought to define (and legitimize) digital rhetoric as a field of study distinct from other academic fields, including rhetoric, human-computer interaction, critical code studies, digital humanities, and internet studies (pp. 13–17, 55–60). While some readers might distinguish digital rhetoric as Eyman defined it from computers and writing, we read them as equitable and, in turn, his book as another example of computers and writing being understood by its relation to writing studies. That is, the starting place for both Eyman’s (2015) and Brooke’s (2009) projects was definition by distinction, what computers and writing is and does as contrasted with what writing studies is and does. From the perspective of their work, computers and writing depends upon writing studies for its identity.

Page 4

The Once and Future (Sub)Field

In the Afterword to The History Book, Hawisher et al. (1996) pointed out the ways in which computers and writing both “followed its parent field” and also “led its parent field” (p. 283, emphases in original). There are dangers, they warned, that exist in both of these positions: 1) focusing so much on keeping up with technological advances that the (sub)field loses sight of its focus on pedagogy and 2) praising new technologies that “can never result in fundamental improvements in the problems teachers face every day—racism; sexism; ageism; systemic bias against individuals for their sexual orientation, their disability, or their socioeconomic status” (p. 284). Throughout this eBook we describe the (sub)field as people-centered, following the lead of Hawisher et al. who attributed the success of the (sub)field up to 1994 to “the people active within that community: people of energy and character who have been individually and collectively generative” (p. 284). Moran used the same characteristics to describe the (sub)field in his interview for this eBook. We likewise found this energy and generativity in those we interviewed. Hawisher et al. also recognized a third “possible danger”: that as the (sub)field ages, it will become “larger and more heavily bureaucratized, less welcoming and supportive to individual teachers” (p. 284). We heard this same concern in the interviews with Cheryl E. Ball and Steven D. Krause for this eBook.

Hawisher et al. (1996) described the interviews interspersed throughout The History Book as “computer literacy autobiographies” and stated that their value was in sharing a perspective about the relationship between computers and writing when it was still relatively new. Hawisher et al. warned that one of the dangers of computers becoming ubiquitous was that they would become “invisible to our eyes, naturalized within educational contexts” (p. 285). Hawisher et al. feared that the newness of the (sub)field and the outsider status felt by many of the interviewees would be lost through familiarization: “This situation may represent a loss of perspective that is difficult to recapture” (p. 285). While our interviews in this eBook cannot possibly capture the “newness” and “strangeness” of those original interviews, the teacher-scholars we spoke with shared a heightened awareness of computers as neither neutral nor natural. That members of the (sub)field all now write and teach writing with computers is evident throughout this eBook, in both the interviews we conducted and the scholarship we review. However, the intellectual impulse to view critically and theorize new emerging technologies is still strong (as we note both in this chapter and in Chapter 2).

While the ubiquity of computers was considered in the later years of The History Book, 1994 was too early for Hawisher et al. (1996) to imagine fully the kinds of mobile devices that were to come. Since The History Book, computers have decreased in both size and price. For instance, the Apple Powerbook Duo 280C, for which The History Book included an ad in its final chapter, was released in 1994 and sold for $3,929.95 (approximately $6,700 in 2019 when accounting for inflation). It can still be purchased at the time of this writing on ebay for $350.

Despite their inability to anticipate the rapid pace of mobile technology advancement, Hawisher et al. (1996) insightfully prognosticated some future developments. They noted pen-based computing in the early 1990s was too costly and too unstable a technology to catch on in any significant way. Hawisher et al. described the failure of Apple’s Newton Message Pad, “the best known Personal Digital Assistant (PDA)” (p. 232), which was advertised as being able to translate writing into print text. They reported that that feature “did not deliver on this promise. The system often failed to recognize users’ handwriting permutations, a tendency that was painfully parodied in the comic strip Doonesbury” (p. 233). It would take until 2015, the final year of our history, before the Apple stylus would work seamlessly with the iPad. Hawisher et al.’s final words in the section of their conclusion on PDAs demonstrate their prescience: “In the long run PDAs like the Message Pad offered not-so-distant, early warning of the hand-held and even wrist-worn devices once imagined only in science fiction and in comic strips” (p. 234). With the introduction of the Apple watch in 2015, the world saw yet another come-to-life example of the once imagined possibilities for mobile computing.

Contributors to Janice R. Walker et al.’s (2011) piece, “Computers and Composition 20/20: A Conversation Piece, Or What Some Very Smart People Have to Say about the Future,” also offered predictions that have likewise been realized. One such prediction was Mike Palmquist’s claim that what educators mean by textbooks will change, particularly that there will be more digital open access (OA) textbooks (Walker et al., 2011, pp. 332–333). Undoubtedly, since 2011 the textbook market has seen a significant presence of OA titles (Barrett, 2019), alongside the rise of MOOCs (massive open online courses) (Krause & Lowe, 2014). For instance, computers and writing specialists Palmquist, Charles Lowe, and Joe Moxley played foundational roles in developing the WAC Clearinghouse, Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, and Writing Commons, respectively, all of which provide free, peer-reviewed educational resources for teaching writing.

Another such prediction was Bill Hart-Davidson, Mike McLeod, and Jeff Grabill’s contention about robots. They declared that “a class of small (or small-ish) automated” robots will “be engaged in conjunction with many—likely most—writing practices, augmenting and extending human capability across what we have accepted for thousands of years to be the range of rhetorical performance: invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery,” particularly automated, mundane writing activities (Walker et al., 2011, pp. 333–334). Grabill later reinforced this contention in his keynote for the 2016 Computers and Writing Conference, “Do We Learn (Writing) Best Together or Alone? Your Life with Robots.” This claim was borne out by, among others, Jessica Reyman’s (2013) and Timothy R. Amidon and Reyman’s (2015) studies of intellectual property concerns for the content automatically created by bots when users engage with social media, commercial, and archival web sites like Amazon, Facebook, Flickr, Twitter, and YouTube.

Two other contributors were especially prescient. Madeleine Sorapure predicted the massive influence of cloud-based computing “to augment or replace single-user, proprietary desktop applications” (Walker et al., 2011, p. 337) and Christine Tulley predicted the move toward writing assessment “at the programmatic level” and the need for digital, web-based tools to assist with this work (Walker et al., 2011, p. 341, emphasis in original). Adobe’s suite of web, image, and video authoring software must at the time of this writing be engaged through the Cloud. And pushes for assessment of writing portfolios (among other grading needs) led to the creation of automated grading technologies like Project Essay Grade and ETS e-Rater.

The predictions made by Hawisher et al. (1996) at the end of The History Book were often accurate, but the authors could not foresee the radical growth of the internet post-1994. What was already astonishing to them at the time of their writing would only grow more so. As they recounted, 1993 was dubbed “The Year of the Internet” and it “exploded into the public imagination” (p. 299). At the time The History Book’s conclusion was written, Hawisher et al. (1996) cited a prediction of 160 million internet users in the year 2000 (p. 237). The actual number of global users in 2000 was 361 million (Argaez, 2005), more than double the prediction. With this growth of “the Net” came “bewildering amounts and kinds of information” (Hawisher et al., 1996, p. 299). The emergence of Gopher, an early search engine, in 1991, and MOSAIC, an early web browser, in 1993, began shaping ways in which people collect, store, and search for knowledge. The historical time period in this eBook saw the birth of Google (in 1998), which still dramatically affects the ways in which knowledge is searched for, organized, and gathered. The influence of Google on these activities will likely only grow.

Hawisher et al. (1996) pointed out the ways in which “computers and compositionists” could use the internet to create their “own neighborhoods, constellations of friends and colleagues from whom they might borrow not a cup of sugar or a lawnmower, but a bit of information[,] a reference, a teaching strategy, a reading list, some needed encouragement in mid-draft” (p. 237). Some of the popular spaces within which to create and maintain these collegial networks were MUDs (multi-user domains), MOOs (MUDs, object-oriented), and MUSHes (multi-user shared hallucinations). The Tuesday Cafe held regularly on MediaMOO at 8:00 p.m. Eastern Time (ET) was frequented by many early computers and writing teacher-scholars. During her interview for this eBook, for instance, Janice R. Walker talked about how when she arrived at her first Computers and Writing Conference, she already felt like she knew everyone because she had been with them in MOOs.

The heyday of MUDs and MOOs ended a short time into the time period we cover in this history (though MediaMOO held on until 2013); however, Twitter came along in 2006, and, with the tagline “join the conversation,” it in some ways took the place of those early MUDs and MOOs as a digital space for academics to share ideas and collaborate. By 2009, the term twittersation had entered the Urban Dictionary. In 2011, Lee Skallerup Bessette and Nicole Papaioannou began #FYCchat, a loosely networked group of writing studies scholars and first-year writing instructors who met virtually via Twitter every Wednesday night at 9 p.m. ET to discuss and share ideas related to teaching first-year writing. In order to recreate a twenty-first century version of the MOO that ended The History Book, Jenn reconvened all six participants from The History Book’s MOO conversation to have a conversation via Twitter (the transcript can be found in the archives section of this eBook).

In their closing chapter, Hawisher et al. (1996) described an online version of the Computers and Writing Conference that was added to the face-to-face versions in 1993 and 1994. The online versions were “designed to accompany or replace the on-site encounters that took place at the face-to-face conferences. [...] The 1993 Ann Arbor Conference drew 367 participants to its on-site conference, and it drew almost half that number—145 participants—to its online conference. Thirty-four of these online participants came only to the online conference” (p. 241, emphasis in original). Since then the guidelines for hosting the conference include instructions for online hosts—a process that was formalized in 2000 (Inman, 2004, p. 5). Not every Computers and Writing Conference since 1994 has had both onsite and online conferences, but there have been quite a few, including

- 1996, a month long online conference hosted by Michigan Technological University concurrent with the onsite one hosted by Utah State University

- 1999, a months long online conference hosted by Connections and the University of Florida that started before and ran after the onsite conference hosted by South Dakota School of Mines and Technology

- 2000, a months long online conference hosted by Connections and the University of Florida that started before and ran after the onsite conference hosted by Texas Woman's University

- 2001, a months long online conference hosted by Connections and the University of Florida that started before and ran after the onsite conference hosted by Ball State University

- 2002, a months long online conference hosted by Nouspace that started before and ran after the onsite conference hosted by Illinois State University

- 2003, a weeks long online conference hosted by Connections and Interversity that ran before the onsite conference at Purdue University

- 2004, a three-week online conference hosted by Tidewater Technological College that ran before the onsite conference hosted by Kapi'olani Community College and University of Hawai'i at Manoa

- 2005, a two-week online conference hosted by KairosNews that ran before the onsite conference hosted by Stanford University

- 2006 a weeks long online conference hosted by Texas Technological University that coincided with the online conference

- 2007, a five-day online conference hosted by AcadianaMoo several months prior to the onsite conference hosted by Wayne State University

- 2008, a five-day online conference hosted by the University of Wisconsin Stout and River Falls campuses that ran several months before the onsite conference hosted by the University of Georgia

- 2009, a two-week online conference hosted by onsite host University of California Davis several months prior to the onsite conference

- 2010, an eight day online conference hosted by Purdue University one week prior to the onsite conference

- 2013, a five day online conference hosted by Frostburg State University shortly before their onsite conference.

Page 5

The Past Several Years: 2016–2019

Our history ends in 2015. As Hawisher et al. (1996) noted in The History Book, histories have to stop somewhere, though they are ongoing: “[T]he project of rediscovering history is never a new undertaking, and, importantly, it is one that is never finished” (p. 281). The period between 2015 and publication of this eBook also saw important developments in the (sub)field, of course. While it is beyond the scope of this project to review them all here, we wanted to end our history by highlighting some important developments.

While always strongly oriented toward issues of social justice, during 2016–2019 the (sub)field was characterized by an even stronger emphasis on (the value of) diversity. For example, “Caring for the Future: Initiatives for Further Inclusion in Computers and Writing,” comprised of reflections from past Gail E. Hawisher and Cynthia L. Selfe Caring for the Future Scholarship winners, was the lead Disputatio webtext in Kairos’s Fall 2017 issue. This piece compiled presentations from Janine Butler, Joseph Cirio, Victor Del Hierro, Laura Gonzales, Joy Robinson, and Angela Haas at a Town Hall at the 2017 Computers and Writing Conference. Participants “share[d] their experiences and their suggestions for increasing diversity and inclusion in the Computers and Writing community.” This same issue of Kairos included another Disputatio webtext devoted to issues of diversity, in particular, physical disabilities. In “The Terrain Less Traveled,” Margaret A. Moore (2017) used “the speech capabilities of [her] AAC [Assistive and Augmentative Communication] device with the camera and iMovie capabilities of [her] iPhone” to share “how, contrary to popular belief, you can still lead a successful and adventuresome life even if you use a wheelchair.” This focus on valuing diversity was further evidenced in the 2017 Kairos Best Webtext Award winner, “Accessible Syllabus,” which compiled “[a]ccessible classroom resources [to] promote student engagement and agency” (Womack et al., 2015).

The years 2016–2019 saw two major discussion boards connected to the (sub)field, WPA-L (the Writing Program Administration’s Listserv) and CRTNET-L (the National Communication Association’s Communication, Research, and Theory Network Listserv), rocked by posts characterized as racist and misogynist (Flaherty, 2019a, 2019b). Critical responses, including from the computers and writing community, were vehement. One response was the creation of the nextGEN Listserv, an international discussion board for graduate students in writing studies. The team of creators, Sweta Gayu Baniya, Estee Beck, Sara Doen, Khirsten L. Echols, Gavin P. Johnson, Lucy Johnson, Ashanka Kumari, Kyle Larson, Lou Maraj, Virginia Shwarz, and Khirsten L. Scott, included scholars affiliated with computers and writing. For their work, the nextGen Listserv Startup Team was recognized with the Kairos Award for Service at the 2019 Computers and Writing Conference (for which, not incidentally, the theme was “Mission Critical: Centering Ethical Challenges in Computers and Writing”).

Additionally, a backchannel conversation in response to the WPA-L posts was started on Twitter with the hashtag #WPAlistservfeministrevolution. A roundtable with Andrew Kulak, Ashanka Kumari, Lydia Wilkes, Patricia Poblete, and Vyshali Manivannan at the 2019 Computers and Writing Conference addressed #WPAlistservfeministrevolution in order to point out how “the uses and abuses of social media remain as gendered, racialized, and homo- and trans-phobic as they were in the early days of social media more than twenty years ago” (p. 81). Moreover, a 2019 special issue of Computers and Composition that focused on “Digital Technologies, Bodies, and Embodiments” included articles on disabilities and the #MeToo movement. As we discuss in previous chapters, this attention to diversity is certainly nothing new for computers and writing practitioners. But during 2016–2019, it was central and unmissable.

Concomitantly, the (sub)field galvanized in its political activism. For example, Elizabeth Losh gave the keynote “Hashtag Feminism and Its Discontents” at the 2018 Computers and Writing Conference. In this talk she analyzed examples of the use of hashtags for feminist political action. This activist focus was likewise taken up that year in the panel “Activism in Virtual Publics,” which included talks by Sandra Nelson, Aimée Knight, and Kristina Fennelly. The same year, Erika Sparby, Katherine DeLuca, Kristine Blair, Rachael Sullivan, Samantha Blackmon, and Stephanie Weaver held a roundtable, “Behind the Scenes of Digital Aggression Research: Identity, Method, Action, and Self-Care,” and since then Sparby has created the Digital Aggression working group (#DAWG), which at the time of this writing meets yearly at Computers and Writing.

Further illustrating this activist turn, the theme of the 2020 Computers and Writing Conference was “Practicing Digital Activisms.” The call for proposals explained,

The Computers and Writing (C&W) community has often developed projects that practice digital activism and advocacy. These practices have evolved quickly in recent years, becoming central to political life around the world. [...] We believe that C&W scholars are poised to be leaders in analyzing, understanding, and using the digital tools that have been taken up for activist and justice-oriented projects. (“Call,” 2019)

As this conference theme and description illustrated, an activist stance has become central to computers and writing. Again, our history supports that such critical civic engagement is not new to computers and writing. But in 2016–2019 it manifested differently and arguably more strongly.

As Chapter 3 illustrates, much can be characterized about the (sub)field through its main conference, Computers and Writing. The conference is a yearly gathering that, as of 2015, was in its 22nd year. Teacher-scholars in the video below discuss the conference’s history, highlighting aspects that have stayed the same and others that have changed. They share personal stories of their experiences at the conference and within the computers and writing community.

Download a PDF transcript of this video.

Page 6

New Directions for Research and Teaching

As did Hawisher et al. (1996) in The History Book, we conclude this history with some predictions and recommendations:

- Online education will grow.

While MOOCs (massive open online courses) did not take off to the degree that some educators had predicted, it is clear that the coming years will bring increased online education opportunities, particularly for adult learners,1 especially as the traditional college-age population of 18–24 year-olds continues to decline (Hussar & Bailey, 2018). This decline is particularly sharp in the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, and Midwest regions of the United States. The success of mostly online provider Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU), for which computers and writing scholar Paul LeBlanc—who was one of the authors of The History Book and who we interviewed for this project—serves as president, is but one illustration of this trend (Adams, 2019). Computers and writing specialists, as LeBlanc has shown, are well poised to take a central role in the development of online programs and institutions. As a (sub)field, we would do well in our research and teaching to attend more to the nontraditional adult population that primarily utilizes such online programs.

As computers and writing specialists (e.g., Blair & Monske, 2003; Hewett & Ehmann, 2004; Krause & Lowe, 2014; Peterson & Savenye, 2001; Reinheimer, 2005) have long attested, investment in online education brings both promise and peril. Online education programs can allow colleges and universities to keep open their doors (virtually at least) and reach a larger percentage of people, especially working adults, seeking education. However, online education programs, particularly large-scale programs at for-profit institutions, often rely on contingent faculty2 who earn low salaries; (must) use ready-made curricula, unified course templates, and standardized syllabi; and lack ownership over course materials to teach online courses.

The Conference on College Composition and Communication’s (CCCC’s) Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for Online Writing Instruction (OWI) (2013) included principles addressing these concerns: “OWI Principle 8: Online writing teachers should receive fair and equitable compensation for their work” and “OWI Principle 5: Online writing teachers should retain reasonable control over their own content and/or techniques for conveying, teaching, and assessing their students’ writing in their OWCs [online writing classes].” Likewise, the Modern Language Association explicitly recommended minimum compensation of $11,100 for a standard three-credit-hour semester course, including online courses (“MLA,” 2019). And elsewhere Purdy (2017) contended that the CCCC Statement of Principles and Standards for the Postsecondary Teaching of Writing needed to be updated to account for new writing technologies, practices, and pedagogies. In particular, he argued that the Statement, among other changes, must explicitly address the realities of digitally-delivered writing instruction and the infrastructures necessary for producing and teaching digital writing. These changes included that “the Statement should make clear that all instructors, including part-time faculty and teachers of online classes, ‘own’ and have control over [...] the materials they create, even (and especially) those distributed online” (p. 232) as well as affirm that “those who teach such classes should be afforded the employment stability, benefits, and support of full-time faculty” (p. 233). However, given examples like SNHU’s pay for adjunct instructors, which is $2,200 per course for undergraduate composition courses (“Online,” 2019), the (sub)field will likely need to continue, as begun in Megan Fulwiler and Jennifer Marlow’s (2014) Con Job: Stories of Adjunct and Contingent Labor, to galvanize its political activism to challenge practices that do not meet these recommendations.

- Calls for diversity, inclusion, and equality will magnify.

Continuing the (sub)field’s feminist origins and increasingly activist trajectory, research and teaching in the (sub)field will grow ever more vigilant about protecting and promoting diversity, equity, and inclusivity. As we report in Chapter 3, keywords associated with diversity, particularly disability and race, appeared in Computers and Writing Conference programs every year between 2006–2015, signalling presentations and discussions about diversity were a consistent aspect of the Computers and Writing Conference the last ten years of this history. Again, a shift in the demographics of college students has helped drive this push, particularly as increasing numbers of students from underrepresented and minority groups pursue postsecondary education (“College,” 2019; Espinoza et al., 2019).

The (sub)field, of course, still has work to do. Adam Banks's books, Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: Searching for Higher Ground from 2006 and Digital griots: African American rhetoric in a multimedia age from 2011, remain the most visible examples of extended critical engagement with race in computers and writing. The larger cultural moment at the time we are revising this eBook, when Black Lives Matter protests are sweeping the United States and abroad in response to the killings of George Floyd and countless other Black Americans and people of color, has laid the groundwork for pushes for racial equality. We expect work in computers and writing to respond to that call. At our own institutions, communities of teacher-scholars are organizing antiracist pedagogy reading groups, researching the colonizing force of language, and offering racial justice grants for research and teaching pursuits.

We anticipate that publication venues and presses will call for researchers to demonstrate adherence to principles of diversity, equity, and inclusivity, for example, by providing screen reader friendly webtexts, by requiring transcripts for video content, and by citing sources from historically marginalized populations. Colleagues, students, and administrators will likewise call for teachers to demonstrate adherence to these principles, for example, by offering course materials in alternative formats and by assigning texts from historically marginalized populations.

- Digital publications will require collaboration.

As the exponential pace of new technological development continues, scholars in the (sub)field will increasingly need to partner with technology specialists, including people outside the (sub)field or even outside academia, in order to be able to publish accessible, cutting-edge webtexts and eBooks. The learning curve to stay current will require the assistance of people whose primary expertise lies in computer science, computer programming, web design, and/or related areas. We encountered this situation in our work on this eBook, for which we turned to Duquesne computer science student Nikolas Schmidt for assistance in developing the eBook’s web interface.

- Writing/communication technologies will privilege nonlinguistic modes.

Although speech-to-text technologies have yet to realize promises of seamless conversion of voice into typed language and Siri (Apple’s intelligent virtual assistant released in 2011) did not run for president,3 we anticipate that the interfaces for future generations of communication technologies will depend less on linguistic text. Rather, they will utilize touch, audio, and image input. In other words, typing will less and less be the means via which people produce text. Thus, “writing” will come less to mean the physical activity of pressing lettered keys (and ever less to mean using pens, pencils, or styluses to handwrite). Again, computers and writing specialists are well poised not only to research and suggest designs for such technologies, but also to teach students strategies for using them effectively and ethically for academic, professional, and civic goals.

- The face(s) of the (sub)field will change.

At less than fifty years old, computers and writing remains a young (sub)field compared to many, but we are now seeing the first of its teacher-scholars begin to retire and, unfortunately, pass away. At the 2016 Computers and Writing Conference, the community marked the retirement of two of the (sub)field’s founders, Gail E. Hawisher and Cynthia L. Selfe. Richard “Dickie” Selfe also retired. And at the 2018 conference, the community celebrated the retirement of Janice R. Walker. As we mention in the Introduction to this eBook, one of The History Book’s original authors, Charles Moran, passed away during the composing of this eBook, as did stalwart conference attendee and dedicated teacher-scholar Will Hochman. While it goes without saying that the conference does not feel the same without these people, it is also continuing to be fueled by the energy and fresh ideas of graduate students and new faculty members, for whom the (sub)field has always prioritized support. Additionally, there is a new generation of teacher-scholars who are seen by others in the community as having made a strong impact on the energy of the conference and the scholarship of the (sub)field. The presence of the (sub)field’s former teacher-scholars continues to live on in the work, minds, and hearts of those who remain to support the community of computers and writing. One thing that we expect will not change is the people-centered focus of the (sub)field. Thus, we end with members of the (sub)field reflecting on their heroes.

We invite readers to contribute their own hero stories or other computers and writing anecdotes and recollections.

Download a PDF transcript of this video.

1:

2:

3:

Page 7