Think-Practicing the Archive

In An Archive of Feeling, Anne Cvetkovich notes that we must understand “gay and lesbian archives as archives of emotion and [potentially of] trauma” (242). In our own take on that in “Queer Rhetoric and the Pleasures of the Archive”, Jonathan Alexander and I claim that the articulation of complex emotions—from anger to resentment to pain and an acute sense of loss, as well as delight in desire and the pleasures of naming desire and claiming community—is central to queer rhetorical work. In a sense, then, archives serve as a distillation of memory and emotion, embodied and yet thought through—felt through the present encountering the past. Or, to play off David Abram, these events—of memory and perception—are instances of the self receiving an echo of itself from the past—an interaction with history from which one returns to oneself changed, refracted somewhat, and through which the past is also reflected, returned to itself afresh (172).

This chapter is not an archive.

But it is a story.

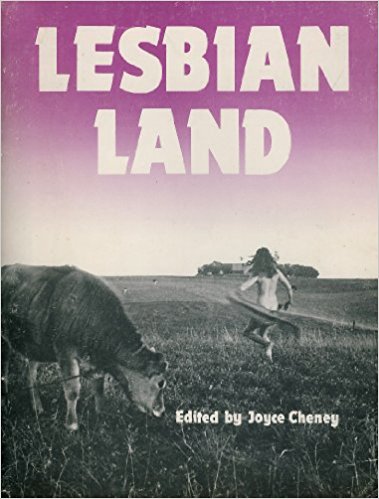

Keeping this embodied echoing in mind, I have moved sideways to explore the diffraction of histories and emotions, nostalgia and often troubling “fact.” I didn’t come to this think-practice deliberately; in fact, I was researching another project entirely, going through my usual research process of scouring the web, searching for full-text .pdfs on databases and printing them, avoiding actual drafting, daydreaming, and buying books on Amazon. There, as a side reference to a side reference, was an out-of-print book. Lesbian Land. A flood, a constellation of memory. Lesbian Land is a 1985 collection edited by Joyce Cheney that offers 30 stories of rural lesbian separatist collectives. At the time of publication, some of the collectives were still in operation, some were dissolving, and some had already disappeared.

The book came out at about the same time I did. It’s part of my history; I saw my first copy in the hands of Nancy, my lover at the time. It was a small press and a small press run. It quickly went out of print, Nancy and I split up, and I lost the book for 30 years. By the time I read the book after I came out in 1984, lesbian communes were kind of done (or so I thought). And yet I was coming out into a lesbian community full of people older than I was, and I ended up being a sort of nostalgic throwback, involved with other throwbacks, or at least older neo-hippies.

I like to think that I've revisited that—first in my dissertation (and then book) on radical feminism, and now in an ongoing, unfinished documentary project on the Furies, a lesbian collective from the early 1970s.

Lesbian separatism in the 1960s and 70s meant distancing oneself as completely as possible from heteropatriarchy—physically, emotionally, sexually, materially—and lesbian separatists held themselves forward as the vanguard activists of United States feminisms at the time. Julie R. Enszer notes that

Separatism as a theory has animated social and political formations for hundreds of years. Various religious groups have practiced separatism with different social, economic, and spiritual meanings. Feminists in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century utilized separatism as an organizing strategy, as have different racial-ethnic groups in the United States and around the world. Black Nationalism and Jewish Nationalism offered inspiration to some lesbians as lesbian separatism emerged in the 1970s. The intellectual roots of lesbian separatism are rich, deep, and complex. (181)

Separatist strategy in the 1960s and 70s found its home in a variety of venues, including urban and rural lesbian communes (such as the Furies in Washington, D.C. or WomenShare in western Oregon), commercial enterprises (such as Olivia Records), publications (Off Our Backs, Country Women, The Furies, Mary Daly’s Beyond God the Father and Gyn/Ecology, among others) and creative works and/or performances, in which performers and artists would only work for all-women audiences.

Alex Dobkin, "View from a Gay Head" (1973)

So the sexes do battle, they batter about.

The mens are the sexes I will live without.

I'll return to the bosom where my journey ends,

Where theres no penis between us friends.

Will I see you again

When you're a lesbian?

Lesbian, lesbian, no man's land;

Lesbian, lesbian,

Any woman can be lesbian.

Every woman can be a lesbian.

Central to the strategy of lesbian separatism was the idea of political lesbianism, which, as Coletta Reid wrote at the time, meant that “women can choose not to be heterosexual, to not support the power system that oppresses them” (qtd. in Enszer 183). Seeing sexual orientation as a powerful, revolutionary political choice was foundational to lesbian separatism in that period (Enszer 183). Such choice, in a sense a statement of belonging-with, afforded one subjectivity within a closed and ironic system: ironic because to be a “real” feminist you didn’t necessarily have to be a “real” lesbian. However, in a number of separatist spaces, you still had to be a “real” woman—subjectivity depended upon conforming to then-mainstream notions of true womanhood, and that meant, at root, being born with a vagina and being assigned “female” at birth. Subjectivity and the agency to speak/act relied on concretized, essentialized ideas of gender.

To return to this story. Lesbian Land is a trace, a memory, both of a unique moment in United States lesbian feminist history and a specific time in my life as a baby dyke. Weaving those moments together points me to a number of interwoven questions about our history and my history, and how those histories are troubled by the moments, the spaces between, the cutting together-apart. This is my think-practice, and it is here I turn speculatively toward queer diffraction.