Coming To Matter

In forwarding DMA as a telling case, I focus on what we do (i.e., attending primarily to providing opportunities for alternative ontologies) and how we do that (i.e., attending primarily to the intra-active becoming of DMA and a DMA girl). Of course, in action, this what and how are enmeshed: at DMA, we design possibilities for alternative ontologies by creating opportunities for participants both to see existing enactments and forces shaping stereotypical entanglements, and to form and be formed by alternative entanglements. The goal for this is to multiply the possible enactments of what DMA and a DMA girl mean, thereby highlighting that DMA and a DMA girl are not static entities that campers step into (what Barad may call a “thingification” where emergent, entangled relationships are turned into static things). Indeed, we want to help girls explore how it is within and through continually involving intra-actions at DMA (and elsewhere) that DMA and a DMA girl become meaningful. A way to understand this intra-active becoming is through the concept of the mangle.

Mangle of Entanglements

According to Andrew Pickering, a "mangle" focuses on the relationships within and between components (i.e., what matters) and effects (i.e., how this matters). As a mangle suggests, something like “DMA” or someone like “a DMA girl” is hardly discretely bounded; rather, it becomes constituted and known through multiple, interdependent, material-discursive chains interacting with other such chains. As such, we encourage campers to examine, expose, and, as necessary, become entangled in different material-discursive chains. When the girls encounter mismatches (e.g., hearing images that girls can do anything, yet discovering how invisible female leaders are in their hometown, as the Sizzle Sisters video demonstrates), we push girls to dig deeper into this mismatch, asking them to examine how actants and actors coordinate, and may be coordinated by, chains of meaning that circulate at DMA.

One example of how we do this is when we ask campers to consider how "a DMA girl" emerges from the intertwining entanglements that surround (among other things) “digital producers” and “tween girls from low performing public schools.” Due to their high learning curves, digital manipulation programs (e.g., GIMP) and digital tools (e.g., video and audio recording equipment) assemble people along a competence continuum, which is not only defined by the time it takes to develop expertise, but by factors that can determine access to technologies in the first place (e.g., educational and family resources). Now consider that DMA campers are eleven-year-old girls, of many races, often from low income neighborhoods, who may have never been on a college campus, and, based on a pre-camp survey, a significant portion of them have limited or no access to digital devices or the Internet at home. The material-discursive gaps between “digital producers” and “tween girls from low performing public schools” is wide, but at DMA we talk about how girls might rework these material-discursive chains, discussing not only what girls can imagine, but also how these imagined possibilities might circulate and with what consequences.

To ground these discussions, we highlight how our engagement with Louisville media has materialized into alternative entanglements that foreground how DMA girls are able to “design their future” (Carter, The Courier-Journal), address the current underrepresentation of women in STEM-related careers (Hebert, UofL Today), and even enact then President Obama’s call for Louisville to be a coder city (Ryan). Girls are thrilled to see themselves or other DMA campers portrayed so positively in Louisville’s newspaper, UofL’s publications, and local TV and radio report—asking us to replay segments and to send them the links so they can share them with their family and friends. However, imagining their future selves as portrayed in these media reports remains abstract. Consequently, we ask the girls what it would look like to them if they were to take up these media images, and we bring in graphic designers, mathematicians, business professors, coders, hackers, and artists for discussions and workshops to make these ideas more concrete. In doing so, we not only hope that the girls will recognize themselves (and be recognized by others) as knowers and doers, but that all DMA participants will be able to articulate and forward additional chains of entanglements during and after DMA.

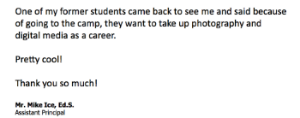

Girls’ uptake of our proposed reworking of typified entanglements varies. Long after camp, we receive many success stories, as when girls, parents, and teachers relay that DMA has sparked new areas of interest and possibly even new careers goals (see email). However, during camp, the responses are mixed. For example, when we encourage girls who want to be architects and doctors to take hard math classes, some seem determined to persevere through middle school algebra while others say girls are just not good in math. This range can also be seen on the required daily blog; when campers responded to the prompt asking how DMA may help them prepare for or think about middle school, one camper wrote (and I quote these eleven-year-olds exactly to share their voices), “i know i can stand up to bullies and stop the chain and also that i may want to be a computer scientist when i grow up because the lady whop came in said it was really fun and I’ve had fun learning about Gimp and iMovie so i would ABSOULUTLEY LOVE to be one” while another camper noted that she was most excited about being able to have her own locker (June 18, 2015). Such comments remind us that, for some girls, DMA introduces new possibilities for understanding themselves, and for others, DMA is likely a blip in their summer.

We also attend to how girls respond to DMA goals through their actions. For instance, when we offer an additional hour to work on digital production after the camp day is over, most girls stay; some girls wrangle with editing software or collaborate with peers to finesse their green screen skits while others create skinny avatars for their video games, something that informed the many body-image conversations we had at camp. Whatever the topic and whatever the girls’ response, we organizers never denigrate; rather, we use activities, blogs, play, and conversations to explore what the girls find valuable. We ask questions about how these values and technological affordances are entangled in associated chains of meaning that are important to the girls. Indeed, our goal throughout is to encourage all of us to understand and participate in the mangle of actors and actants coordinating opportunities so that we all understand how girls can see themselves in multiple ways.