Practice What You Preach:

Part of collaborating on a project is finding the right people to work with, but sometimes those people in the world of academia are miles apart. Such was the case with our editors for Soundwriting Pedagogies, Courtney S. Danforth, Kyle D. Stedman, and Michael J. Faris, who offer us a glimpse into how a notion of collaboration turned into a phenomenal book project that performs the very act it argues for within its figurative covers. Stedman writes when reflecting on this project, “I know of no other collection of webtexts that can also be subscribed to in your favorite podcast app. Yes, some chapters make more sense than others in the audio-only context, but that’s part of the fun and excitement. I think we broke new ground there.” The editors of Soundwriting Pedagogies allow us to see parts of their own creative process and the affordances and constraints they faced when taking on a project of this caliber. Our glimpse into the project from start to finish provides future authors of digital books some considerations as they think about taking an idea from start to digital finish.

Finding your People

Often when one meets people at a conference or event who are talking about the same things you are, there’s instant affinity. Later that affinity turns into an idea and an overture of collaboration. Danforth had always been interested in sound, but “started teaching soundwriting in a context of disability”;“that’s the direction my work is taking.” She saw a gap that she and her co-editors might be able to fill as “There was an exciting subfield of sonic rhetoric emerging but so much of the scholarship was intensely theoretical.” So...she reached out to Stedman in an email:

9 Dec 2014, Courtney to Kyle: I like working with you. Would you be interested in co-special-editing a journal issue on soundwriting pedagogy?

While a journal issue did not end up materializing, Danforth saw a possibility to look at teaching in different way and could see this being something larger like a book. She writes, “As faculty at teaching institutions, Kyle and I wanted to read more about how our colleagues were applying that theory in the classroom. Since that book didn’t exist yet, we decided to make one ourselves.” In an email to Danforth, Stedman began brainstorming:

25 March 2015, Kyle to Courtney: But I could see something like this happening: 1) CCDP publishes an edited collection on the theory and practice of sound from a rhetoric and composition perspective, writ large. I could write a chapter. So could you. We could all write chapters! But then: 2) Me and you work on something smaller, a collection of "case studies" as you said, or something else that really dives into the real, live practice of sound-teaching.

25 March 2015, Courtney to Kyle: I am on board for any/all of what you list. My motivations include: 1. I want to work on soundwriting pedagogy. 2. I want to write. 3. I want to find out what other people are doing with soundwriting. 4. I want to work on something with you. 5. My instinct was to do #3 before doing #1, but I suppose that isn't really mandatory.

As the ideas cemented and grew into a full blown project, Danforth realized that she and Stedman could not do it alone. “We put out an audio CFP in the summer of 2015 and quickly became so overwhelmed by the response we begged Michael to help us. Luckily, he agreed.” Reaching out to Faris provided him an opportunity he had not explored thus far in his career as his “previous (and continued) scholarship focused on pedagogical problems related to new media, and I had been working as an editor at Kairos when Courtney and Kyle asked me to join the editorial team.” Faris’ email of interest in joining the team reflects his view that this venture would be beneficial within his classroom and beyond.

13 Jan 2016, Michael to Courtney and Kyle: “What an exciting project! It’s great to hear that you got so much interest from contributors and have expanded the project. I’m excited by the opportunity to help — a bit worried about how much time it might involve. I think it would be great experience, and might help me conceptualize a few graduate and undergraduate courses and assignments I’ll be working on for next year (undergraduate writing courses and graduate new media courses), so I’m definitely interested!”

Making Tough Decisions

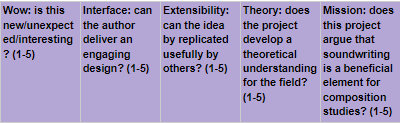

With a successful CFP, our editors were faced with some tough decisions. Stedman recounts their first thoughts, “Of course, we needed a publisher that was on board with our vision. We went with CCDP because they’re well-known as supporting exciting born-digital work, but they also wanted to keep an edited collection at 10 chapters or fewer, while we were initially imagining something much larger.” With so many proposals submitted, that led to a tough series of decisions on who to accept, so Danforth and Stedman developed a 5-point rubric that judged each proposal on the following traits:

Five-point rubric used by Danforth and Stedman

After determining which chapters they would include in their collection, the question then became one of how to produce a text digitally when skill levels for producing webtexts varied. This variety in skill created one of the biggest challenges Faris found in

“designing it and getting it to work. We asked chapter authors to design their chapters as webtexts, some didn't have the ability to design html pages, and a few authors submitted chapters in formats that weren't sustainable or easily transferable to a publisher. I offered to design the html for those chapters, each of which went through multiple iterations as we discussed with authors what would be the best design for their chapters.”

This time inclusive process sometimes involved re-coding or coding from scratch because the interface of the various coding platforms did not transfer in ways that matched up.

Putting it All Together

Part of creating a digital book is figuring out how it all fits together, and this may prove difficult when you have a variety of designs being used. Faris discusses how “The book's landing page/TOC and introduction went through multiple design prototypes before we decided on the final version.” To facilitate better navigation and create consistency, Faris created a header and menu for the whole book.

"This was an early prototype of how the landing page might look. We decided against it because it was just too dark and we liked the lighter look of our current design more" -Danforth

Faris's designs went far beyond the book as a whole's landing page. For instance, here's an example of an early design for the Introduction chapter:

"This was an early prototype of how the introduction might look. We later revised this appearance because we wanted to forefront audio, so we made the home page of the introduction just feature the audio of the whole introduction, and then separated out listening/reading parts of the introduction onto different pages." -Faris

Both the landing page for the book and the design of the Introduction chapter needed to reflect the spirit of the project not only in format but in content. This required the authors to meet remotely to discuss their goals. We are fortunate to be privy to one of their first conversations that gives us a peek into their framing and goals for the entire collection.

Audio clip of Courtney and Kyle April 26, 2016 meeting about the introduction:

Transcript of Courtney and Kyle April 26, 2016 meeting about the introduction

On top of creating a framework for the whole project, the editors also collaborated heavily on the preface to the collection, the set ups to the various chapters, and the introduction chapter, which was no small feat. Below is a screenshot of their first draft of preface of introduction chapter along with notes and edits.

"The original beginning of the whole introduction, which we scrapped in favor of our 'sharing sounds' concept." -Stedman

Audio clip of the original beginning of the introduction:

While this process looks neat and tidy from the screenshot above, Stedman shares that this lengthy introduction took many months to create:

“The version we sent to reviewers along with our prospectus was actually completely revised and rerecorded for the final book; the original had been recorded over multiple sessions, with lots of edits spliced in that were obviously recorded in other spaces. We also had to address pacing issues, clarifications of some of our points, adjustments to our style (this was informal, but how informal should it be?), and other nagging things that were bugging us. (I, Kyle, listened to that original version a few times in the car, and if something bugged me too much I made a note.) Eventually, with revised script in hand, we sat down and rerecorded the whole thing in one sitting, which greatly helped the audio quality, and the coherence of our ideas.”

Revising audio can prove difficult, and our editors have allowed us to not only see their processing up above but in recording iterations of a later part of the introduction to the collection. Below is a screenshot of a later portion of the introduction.

Screenshot of the introduction

The goal of the introduction was “to be casual and personal, but this is an example of when it perhaps went too far, meandering into stories that weren’t really connected to the topic at hand. Notice that this was back when we were calling Michael a 'technical editor,' before we realized that that he was oh so much more than that.”

Audio clip of the Madonna/Pink Floyd moment:

It wasn’t just the introduction text that took several iterations. Title pages for the chapters also needed to fit into the overall theme. This is an example of the iterations that one chapter title page went through as the final format moved toward something the authors felt meshed with the project as an overall concept.

The progression of design for one of the chapters from an early iteration to the final design

Final Draft

Being able to edit easily in a document is something writers take for granted, but when html is involved, changes and revisions become complicated. Passing html files back and forth is not easy, so our editors “requested changes as lists in emails or using track changes in Google Docs, which led to dozens of emails with each author about their chapter and manually transferring changes from Google Docs to html files.” These exchanges resulted in a well over 1400 emails for this project alone in a 2.5 year period! Creating a workflow system and managing content becomes a must. Faris writes, “Numerous times, we had to ask ourselves, Is this the most recent version of the audio they sent? Or, where did we put that file? We worked through email, Google Drive, and Dropbox, which most of the time worked fairly well, but sometimes meant we forgot where something was stored or if we had communicated something with an author or not.”

Even in creating a navigable landing page/TOC, getting codes to mesh between the chapters required troubleshooting since the vastly different designs of the contributing authors varied. Faris explains, “For example, the css and javascript for the menu sometimes conflicted with css and javascript in individual chapters, and we had to do lots of tweaking to get it to work on some chapters.” This proved to be challenging but also enjoyable as Faris was tested with “imagining and testing what a sound-based and html-based book could look like,” and even though it took time, “it was also a lot of fun to test out ideas and troubleshoot problems.”

Not only did their own audio frame the book, the authors had to lean on their contributors to perhaps move out of their comfort zones. Faris shares, “Because audio-design and audio-editing are fairly new for most scholars in rhetoric and composition, another challenge was deciding when to ask for revisions to audio: Audio recording and editing can be time-intensive, especially for scholars trained to communicate scholarly work in alphabetic text.” Because of the time intensive work of audio, the editors respected their contributors and made suggestions to edit if possible on the contributors’ end or took care of minor problems like audio shifts themselves. Some contributors really embraced their chapters in surprising and nuanced ways. Danforth describes:

“The first time I heard a draft of Jeremy and Shannon’s chapter and they just call up Cindy Selfe? It blew me away. That’s the power of an audio citation. And then in Milena and David’s chapter, they let us listen in on a dinner party they have with Hildegard Westerkamp. Where else in the history of scholarly writing does something like that happen? This collection could not exist without the work of both these tremendous scholars, but we don’t just have their words on a page, we’ve got their living, teaching, voices enacting their ideas for our ears.”

The Finished Product and Beyond

After completing this book, our editors have only just begun to explore what soundwriting pedagogy looks and sounds like. Where to go from here? Each editor weighs in on the next steps for his or her work or study.

Faris’ work with Soundwriting Pedagogies had opened up his teaching: “Working on this project has really gotten me engaged in soundwriting: I've started teaching soundwriting in graduate courses, started a podcast (though I'm far behind in getting new episodes), and now that I administer TTU's First-Year Writing program, all of our undergraduates in ENGL 1301 are creating podcasts (an assignment I built off of Jeremy Cushman and Shannon Kelly's chapter). That's potentially 2700 podcast episodes this fall! I'm looking forward to continuing to write/create scholarship about and in audio.”

Stedman encourages other to take these ideas and run with them: “The next step beyond that is of course classroom practice: people using and remixing these ideas in their own classes, and then finding ways to share them. Most of the book is licensed with the very-open Creative Commons BY-NC license, which gives people the legal right to remix the words and audio files into their own contexts. So hopefully, the effect of the book will be a host of soundwriting assignments in the world throughout all sorts of distribution platforms.”

Danforth believes that they have only just begun in changing writing pedagogy, and “there is a sequel (of sorts) in progress! There has been so much interest already in pedagogical applications of soundwriting, we’re pretty far along now editing a second collection focused even more granularly on classroom activities and assignments that use sound to teach writing.”

Revisiting Familiar Places and Exploring New Spaces

The name Alexandra Hidalgo may be familiar to those of you who are familiar with our books. Her video book, Cámara Retórica: A Feminist Filmmaking Methodology for Rhetoric and Composition, was published in January of 2017 by our press and shows readers how they can re-vision composition. In her introduction Hidalgo explains that the book is:

“comprised of six video-essay chapters that connect film and video production, feminist filmmaking, and Rhetoric and Composition. Drawing from interviews conducted with ten faculty and graduate students in the field who produce and teach the production of moving images, as well as original footage and clips created by rhetoricians and filmmakers, Cámara Retórica weaves a visual and aural tapestry that performs the kind of feminist, moving-image scholarship it argues can be transformative for Rhetoric and Composition.”

Recently at the Computers and Writing Conference at George Mason University in Virginia, Cámara Retórica was awarded the Computers and Composition Distinguished Book Award, which “honors book-length works that contribute in substantial and innovative ways to the field of computers and composition.”

Pictured above: Hidalgo and visual artist Gina Washington film each other.

Hidalgo describes the difficulty many scholars feel when asked to define their scholarship, which oftentimes combines a variety of interests into a niche they feel compelled to work on. Those niches, which do not quite fit perfectly into the various fields, make for delightful study but also result in unease as those fields can tug at scholars to declare their allegiance. Hidalgo writes,

“Since the first year of my PhD, I have been straddling two fields: rhetoric and composition and documentary filmmaking. In a less enlightened discipline, that might turn me into an outsider, but my work, as hybrid as it is, has been received with open arms by my colleagues over the years. However, although I’ve won numerous film festival awards for my documentaries, I’d never won an award for my scholarship. Receiving the Distinguished Book Award made me feel like I’m managing the balancing act of working in two fields. I hope, above all, that it inspires more rhetoricians to pick up the camera and explore film and video production. I’m eager to watch filmmaking continue to evolve in our field.”

The Computers and Composition Distinguished Book Award comes as Hidalgo is in production and editing her second feature documentary titled The Weeping Season. The film, which is 14 years in the making, explores her feelings of loss and love for her father. This poignant reflection on her father’s disappearance and how it has impacted her demonstrates yet again her ability to move an audience through image and narration.

As Hidalgo nears the completion of The Weeping Season, she considers what she wants her audience to feel as her film comes to a close. She writes:

“It’s hard to know what you want an audience to walk away feeling about a film you haven’t yet completed. I hope that they find the story and the characters compelling. You always want those moments as a filmmaker when a everyone gasps or sighs or when you hear quiet sniffles coming from all directions in the room. It means that you’ve moved your audience, touched them in ways that linger for them and are often cathartic. I do hope, and I think we’ll manage to pull this off, that when people watch the finished product they can look back at their own individual, familial, and national losses and feel a renewed urge to turn those wounds into creativity and hope.”

2018 Trailer for The Weeping Season from Alexandra Hidalgo on Vimeo.

The Weeping Season centers on memory, which can be slippery as the passing of time causes recollections to be filtered and re-remembered differently. As Hidalgo sought to find answers about the disappearance of her father, she had to rely upon more than just her memory for this memoir. She writes,

“I’ve been fortunate in having a transformative experience working with relatives and family friends on this film. Everyone I’ve wanted to interview has been ready to talk about my dad and to deconstruct his life, his spellbinding personality, and his vanishing. There are moments when people’s recollections don’t quite match up and those are some of my favorite moments to feature on the film because three decades later you can’t really have a perfectly cohesive narrative. This is as much a film about loss as it is about the worlds we construct through our own personal blend of recollection and longing.”

Pictured above: Hidalgo showing her aunt Yarima Hidalgo how the camera works before interviewing her.

Rhetorically, Hidalgo also asks us to consider how we think of and construct memoir in her video essay entitled, “Creating Our Pasts Together: A Cultural Rhetorics Approach to Memoir” published in The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics. In her essay, she narrates how the difficulties of composition as choices, created in the reconstruction of memory and memoir, significantly impact the text and the lives of those who contributed to the text’s creation. How do we ethically navigate those choices in our compositions? Her answer and exploration of this topic is in the video below:

Cultural Rhetorics Approach to Memoir from Alexandra Hidalgo on Vimeo.

Since finishing Cámara Retórica, Hidalgo has continued her work with feminist filmmaking and maintains her production company’s monthly community letter about the work she’s involved with and what is important in filmmaking scholarship.

“The Sabana Grande Productions Community Letter came from a suggestion from my filmmaking mentor Carole Dean, the brilliant and kind founder and president of From The Heart Productions. She explained that even though most of us have overflowing inboxes, a well-crafted and purposeful community letter can foster a vibrant and personal connection with audiences. So far, even though it seems daunting to come up with engaging content each month--and to do so in two languages, no less--the reception to the letter has been exceptional with enthusiastic responses from a wide range of people, from the expected dear friends and family to people I’ve never met. I think in academia we sometimes feel like marketing and outreach are dirty words, but in film if you don’t create audiences for your work, no one will fund your projects. The great thing about the community letter is that it also allows me to get more exposure for my peer-reviewed publications. It’s time consuming but a fantastic way to get your work out there.”

If you care to see what Sabana Grande Productions is up to, you can subscribe to it. You can also check out their previous issues. In these issues, you can see Hidalgo’s projects use the medium of film to create and expand spaces as they cultivate a spirit of activism which strives to make the world a kinder place for all.

As our society becomes more and more focused on multimodal communication, film and its uses have adjusted how we talk about composition and argumentation in the Composition classroom. This discussion has been uneven and deserves more emphasis. Because she straddles both rhetoric and composition and filmmaking, Hidalgo finds that “it is imperative for scholars to think about ways to reach audiences through the moving image medium that they find so engaging.” She argues in Cámara Retórica, “one can make profound and impactful arguments by uniting the moving image, the sound of our voices, and music. It’s a particularly powerful way to reach an audience and well worth the extra work of learning how to use a camera and how to edit software.” While she does not believe that every scholar needs to go out and buy filming equipment, she does believe “video essays and documentaries will continue to grow in prominence in our field and in academia in general” because “through moving images we’ll reach wider audiences and share our ideas on much bigger platforms.” Learning a new way of composing through video “can pay off in spectacular ways” and is worth the extra work as it can allow us to compose multimodally about issues that matter most to us.

The CCDP Fellows Program

Computers and Composition Digital Press seeks graduate students to serve as CCDP Digital Fellows and assist in the creation of digital materials to promote Press titles and initiatives for the 2018 – 2019 academic year.

Duties may include:

- Conducting interviews with CCDP authors

- Contributing to the CCDP Scholar Electric Blog

- Serving as CCDP Ambassadors at professional conferences

- Soliciting book reviews of CCDP titles

- Contributing to CCDP social media initiatives

- Collaborating with Promotions and Social Media Editor on other projects

Applicants should be graduate students with research interests in digital rhetoric, digital publishing, and/or social media. Experience in blogging or maintaining professional social media accounts a plus.

Time Commitment

This is a one-year appointment, and CCDP fellows can expect to work on two small projects per semester – i.e., a blog post, interview, or social media campaign. Fellows are also required to participate in Skype meetings no more than once a month with the other CCDP Fellows and the Promotions and Social Media Editor.

Benefits

This is a volunteer role; however, this position will give the Fellows experience working with a leading digital press, connecting with scholars in the field, and gaining early access to upcoming scholarship. Fellows may have the opportunity to publish on their work with CCDP in collaboration with the Promotions and Social Media Editor. Fellows are also encouraged to use their experience with CCDP in their own scholarship and teaching.

To apply, please send a CV and a letter of interest to the CCDP Promotions and Social Media Editor, Amber Buck, at ambuck [at] ua.edu. Applications are due on August 31, 2018. Please direct all questions and inquiries to Amber Buck.

Summer Updates from CCDP

We also have some new initiatives planned for our blog. We're currently soliciting CCDP Digital Fellows who can help us with some blog and social media initiatives over the coming year. Are you or do you know someone who is a graduate student in rhetoric and composition with blog and social media experience? Please apply!

We'll be busier over here on the blog this summer, as have some excellent content forthcoming from our Associate Editor Kelly Wheeler and our first CCDP Digital Fellow Stephanie Parker. Watch this space for updates on digital publishing and accessibility, interviews with authors, and teaching materials to accompany some of our titles.

And while we're at it, don't forget to add our titles to your summer reading list. A good deal of our content is downloadable for the plane, the beach, or wherever you might be traveling this summer.

And the Award Goes to...

Each year, Computers and Composition, “a professional journal devoted to exploring the use of computers in composition classes, programs, and scholarly projects,” awards the Computers and Composition Michelle Kendrick Outstanding Digital Production/Scholarship Award. The award, dedicated to Michelle Kendrick who passed away in 2006, recognizes

“the creation of outstanding digital productions, digital environments, and/or digital media scholarship. It acknowledges that any single mode of communication, including the alphabetic, can represent only a portion of meaning that authors/designers might want to convey to audiences. As does our field, this award recognizes the intellectual and creative effort that goes into such work and celebrates the scholarly potential of digital media texts and environments that may include visuals, video animation, and/or sound, as well as printed words.” (Computers and Composition website)

We are happy to celebrate that our very own Computers and Composition Digital Press was awarded this award at the Computers and Writing Conference held at George Mason University this past May.

This award...

MELANIE, TIM, or PATRICK maybe a quote on what this means for the press????