Chapter 3

Seeking Guidance for Assessing Digital Compositions/Composing

Charles Moran and Anne Herrington

![]()

ABSTRACT

Drawing on our experiences co-editing (with Kevin Hodgson) Teaching the New Writing: Technology, Change, and Assessment (2009) and on our experiences curating the National Writing Project Digital Is web site, we focus in this chapter on territory that has yet to be fully explored and mapped: the assessment of students’ digital projects. Although many resources exist—shared by enthusiastic teachers and students—that frame, situate, and present digital projects, few resources exist that provide guidance for assessing students’ new writing. In this chapter, we argue that teachers’ actual practice, directly observed in context and in tandem with specific classroom materials, is the best source for that guidance. We first present position statements and state standards documents, then focus on two teachers’ classroom practices and materials as models of best practice in digital writing assessment and evaluation.

![]()

For many teachers, particularly those themselves not fully immersed in digital composing, bringing digital writing into the curriculum proves a challenge. Once teachers have taken this difficult step, and their students have produced the assigned multimodal or networked texts, the teachers face the next challenge: assessment. Is the mix of text, graphics, and sound “good?” According to what criteria? Which rubrics? We don’t mean to suggest that the assessment of traditional, print-only student composing is easy. Our long history of writing assessment, and the debates that have surrounded it, tells us that assessment of student composing, whether the texts be pen-and-paper or digital, is a complex and difficult topic. Our field’s exploration of holistic scoring in the 1980s was an attempt to move beyond earlier writing assessment that tended to focus on word-and-sentence-level error. Today, the debates around computer scoring of student writing and the general unease about the accuracy and “washback” consequences of large-scale writing assessments tell us that the issues around print-and-paper writing assessment are complex and not likely to be soon resolved.

The development of emerging technologies has so increased the apparent difficulty and complexity of assessing student composing that as teachers we are glad to describe student adventures in multimodal composing, but when it comes to laying out our assessment procedures or criteria, we are most often silent. We say this based on our experience as editors of a recent book, Teaching the New Writing: Technology, Change, and Assessment (2009), co-edited with Kevin Hodgson, and as curators with the National Writing Project’s (NWP) Digital Is teacher resource. When we called for manuscripts for Teaching the New Writing in 2008, we asked for descriptions of classroom practice in teaching multimedia composing, descriptions that included, given the book’s subtitle, particular focus on assessment procedures. As the chapters developed, we found that we had to keep bringing many of the authors’ attention back to assessment. The authors were clearly superb teachers who were excited by the opportunities offered their students as composers in new media. But summative, teacher-based assessment was not their principal concern. And when, as curators for the NWP’s Digital Is web site, we proposed a collection around assessment of multimedia, we discovered that at that time there were very few on-site resources that had anything to do with assessing digital compositions. We are pleased to see that the NWP Multimodal Assessment Project Committee (2011; see Chapter 7, this volume) is addressing this dearth of material as are other print books: for example, Troy Hicks’ The Digital Writing Workshop (2009), and the National Writing Project’s Because Digital Writing Matters (2010). Yet, as the authors of these works acknowledge, the assessment of students’ digital projects is still a work in progress—new territory yet to be fully explored and mapped.

Our aim in this chapter is to consider some of the sources we might turn to for guidance for assessing students’ new writing. We will argue that the best source is teachers’ actual practice, directly observed. Given that this is not possible here (without multiple videos, which would give you more detail, and take more time, than is entirely necessary), we will present two teacher-reports of their own classroom practice, as fully contextualized and as close to classroom observation as we can get. We will also survey presently available state standards documents and position statements developed by our professional organizations to guide us in assessing digital composing. But first we want to see what the web has to offer in the form of tip sheets for multimedia presentations, a source that we feel does have something to tell us, however decontextualized its advice may be.

TIP SHEETS: BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY

Tip sheets developed for business and industry offer advice to users that we could convert to criteria in assessing students’ digital writing. Many of these tip sheets begin with KISS (Keep it Simple, Stupid), and follow with precepts such as “don’t use borders”; “fill the slide to the edges”; and “use the largest possible typeface.” Typical of these tip sheets is “10 PowerPoint Tips for Preparing a Professional Presentation,” posted by Tina Sieber on MakeUseOf, a web-based collection of guides. In addition to the ever-present KISS, Sieber includes advice such as “Use keywords,” “No sentences!” and “Decorate scarcely but well.” On another tip sheet, Garr Reynolds presents “Top Ten Slide Tips” and advises the use of non-serif typefaces and “plenty of ‘white space’ or ‘negative space.’” We could look, too, to the more scholarly work of Edward Tufte, who lays out his criteria for good graphic design in The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (1983), contrasting his sense of good graphics with what he terms “chartjunk” (p. 121). And available to us also are tip sheets on web site and blog design, often focused on what is termed “usability.” Good examples of blog design tip sheets are Jakob Nielsen’s “Weblog Usability: The Top Ten Design Mistakes,” and Jeff Atwood’s “Thirteen Blog Clichés, ” both focusing on what not to do. For example, Nielsen identifies such mistakes as mixing topics in a single blog entry and failing to identify links. Atwood points to such “clichés” as “mindless link propagation” (excessive linking with too little original content) and “This Ain’t Your Diary” (personal diary-type entries).

Tina Sieber, “10 PowerPoint Tips for Preparing a Professional Presentation”

http://www.makeuseof.com/tag/10-tips-for-preparing-a-professional-presentation/

Garr Reynolds presents, “Top Ten Slide Tips”

http://www.garrreynolds.com/Presentation/slides.html

Jakob Nielsen, “Weblog Usability: The Top Ten Design Mistakes”

http://www.nngroup.com/articles/weblog-usability-top-ten-mistakes/

Jeff Atwood, “Thirteen Blog Clichés”

http://www.codinghorror.com/blog/2007/08/thirteen-blog-cliches.html

Although some of these injunctions ring true, this readily available advice is not fully useful to us as teachers of apprentice digital writers for a couple of reasons. First, the advice is decontextualized and highly abstract. What, after all, is “simple?” And what can we usefully take from “decorate scarcely but well?” And, second, the advice speaks only to the assessment of the final product. As teachers, we are interested not just in the final product, but the learning that takes place during the composing process. The slideshow tips available on the web are aimed exclusively at business users, and therefore consider the presentation—the product—only. And, despite the interactivity of Web 2.0, web design and blog design tips are also product-oriented, limited in their scope to aspects of the final portal, site, or blog. We need to look beyond the tip sheets designed for industry for assessment guidance for students’ digital composing.

POSITION STATEMENTS AND STATE STANDARDS

In our search for help with assessing students’ digital writing we can turn to position statements and policy documents developed by professional teachers’ associations and state departments of education, including the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) Curriculum and Assessment Framework: 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment Framework (2008), the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing (Council of Writing Program Administrators, NCTE, and NWP, 2011), and the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects (2010), developed by the Common Core State Standards Initiative and now adopted by 45 states. All three of these documents are valuable because they broaden our focus from the features of specific types of texts to the skills that we want students to develop: for example, collaborating with others, using the Internet both for doing research and publishing texts, and creating texts for various purposes and audiences. Assessing these skills in a classroom takes us beyond the tip sheets’ narrow focus on a single text.

NCTE, "NCTE Framework: 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment Framework"

http://www.ncte.org/positions/statements/21stcentframework

Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and the National Writing Project, "Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing"

http://wpacouncil.org/files/framework-for-success-postsecondary-writing.pdf

"Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects"

http://www.corestandards.org/assets/CCSSI_ELA%20Standards.pdf

Of the documents listed above, the broadest is the NCTE Policy Statement, 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment Framework (2008), geared primarily toward K–12 English language arts instruction. It addresses important technological skills, composing skills, and even social skills, as well as ethical and cultural awareness and responsibility. As its title indicates, this document aims to guide both curriculum development and assessment of curricular outcomes. For instance, taking this document as a guide, a teacher would design curricula that would involve students in “build[ing] relationships with others to pose and solve problems collaboratively and cross-culturally.” Although this outcome might initially seem difficult to assess, one could assess how well a culturally diverse group of students work collaboratively, say, via a blog, to discuss and reach some consensus on approaches to addressing a societal problem. Criteria for assessment might then include evidence in blog postings of receptivity to viewpoints that differ from one’s own and consideration of various cultural perspectives in developing a solution. The “Be A Blogger” project that we present later in this chapter also aims to develop “interpersonal skills in order to work collaboratively,” to foster understanding across differences, and to engage in collaborative problem solving. Another noteworthy element of the NCTE Curriculum and Assessment Framework is the need to “attend to the ethical responsibilities required by complex environments,” including not only the legal and ethical use of sources but also “ ethics and safety exhibited in students’ online behavior.” Attending to this broad concern, Kevin Hodgson, a teacher at William E. Norris Elementary School in Southampton, Massachusetts, teaches a “Digital Life” unit that includes topics of protecting one’s privacy; legal and ethical use of sources; and the ethics of participating online, including issues of cyberbullying. The culminating project for the unit is a digital poster that includes both text and images. The evaluation criteria include representing at least three topics of the unit, teaching viewers about the topics, and using elements of good design (something also taught in conjunction with the unit). Assessing the digital poster in terms of design evidences another of the elements of the NCTE Curriculum and Assessment Framework, one identified as “newer aspects of assessment of 21st century learning”: the “extent to which tools can make artists, musicians, and designers of students not traditionally considered talented in those fields.” For the digital poster those design elements included, for example, images and video being partners to the text and having a consistent theme for background, text, and images. In Because Digital Writing Matters, Troy Hicks (2010) provides the example of a curriculum unit and assessment designed by Sharon Murchie asking students to create public service announcements that include text, visuals, and music; the PSAs are assessed on all three components.

The Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing (2011) takes a somewhat different approach. It was developed collaboratively by NCTE, WPA, and NWP to provide another view on “college readiness” while the Common Core State Standards were being developed. The aim was to impact K–12 policy and practice. The document is distinctive for addressing experiences with writing, reading, and critical analysis” by foregrounding “habits of mind that are crucial to success in college” (p. 6). The eight habits of mind identified are “curiosity, openness, engagement, creativity, persistence, responsibility, flexibility, and metacognition.” Embedded in the section on experiences are statements of specific knowledge (e.g., “rhetorical knowledge”) and skills (e.g., “flexible writing processes” and “ability to compose in multiple environments”) that students need to develop. The focus is on providing teachers with ways to help students develop the skills and knowledge while also engaging in the habits of mind. For example, one aspect of developing a flexible writing process that would also foster meta-cognition is for students to “reflect on how different writing tasks and elements of the writing process contribute to their development as a writer.”

Unlike the Common Core State Standards (2010), which identify specific assessable outcomes, the Framework for Success (2011) is not an assessment document. Still, by identifying specific traits deemed critical for college success, it sets up the basis for assessment. Further, by stressing habits of mind and linking them to approaches to teaching specific knowledge and skills, the Framework for Success is a generative antidote to overly skills-focused curriculum and assessment guides.

One limitation of the Framework for Success (2011) is that the section on composing in multiple environments seems to assume an individual composer. Unlike the NCTE Curriculum and Assessment Framework (2008), the Framework for Success does not highlight collaboration as a needed skill. Although it does include listening to others to learn from them, it doesn’t include working with others, with the exception of the writing process section, which does include “work with others in various stages of writing.” This statement seems more linked to working with others to give and receive feedback for revising, however. The Framework for Success also does not address ethics, with the exception of noting the importance of being able to “engage and incorporate the ideas of others, giving credit to those ideas by using appropriate sources” (p. 5). In sum, although we endorse the focus on habits of mind and goal of fostering them, the Framework for Success seems to be a more limited document than the NCTE Curriculum and Assessment Framework. That more limited focus may reflect the national educational policy debate over “college readiness” in which NCTE, NWP, and WPA were attempting to intervene. While it has the strength of focusing on habits of mind, perhaps because it is geared to “college readiness,” it reflects the narrower literacy focus still dominant in colleges: single-authored, alphabetic text essays and arguments.

The Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects (2010) are the result of a multi-year, multi-state initiative to “define the knowledge and skills students should have within their K–12 education careers so that they will graduate high school able to succeed in entry-level, credit-bearing academic college courses and in workforce training programs.” They have now been adopted and incorporated into the state-mandated K–12 curriculum frameworks of all but five states. For the ELA Common Core, technology is embedded within the Reading, Speaking, and Writing Standards. One of the Writing Standards directly addresses the use of new media: “Use technology, including the Internet, to produce and publish writing and to interact and collaborate with others” (p. 42). As with the NCTE Curriculum and Assessment Framework (2008), collaboration with others is identified as a valued skill that students must demonstrate, starting as early as kindergarten. Another Writing Standard also includes using digital sources for research purposes, being able to evaluate these sources, and avoiding plagiarism. As with the Framework for Success (2011) and in contrast to the NCTE Curriculum and Assessment Framework , ethics are not explicitly mentioned. The Writing Standards do not explicitly address multimodal texts, although one of the standards for Speaking and Listening does focus on the skill of using visual information and audio to supplement an oral presentation: “Make strategic use of digital media and visual displays of data to express information and enhance understanding of presentations” (p. 48). The specific standard for grades 11–12 calls for students to “make strategic use of digital media (e.g., textual, graphical, audio, visual, and interactive elements) in presentations to enhance understanding of findings, reasoning, and evidence and to add interest” (p. 50). While pointing to multiple modes, the standard does not identify criteria for evaluating these “strategic uses.” More significantly, in contrast to the Frameworks for Success, the Common Core State Standards are not anchored in broad habits of mind that would drive how the skills and knowledge are taught.

As we think about assessing students’ digital composing, what is most useful about these documents is that they take a broad curricular perspective, the NCTE Curriculum and Assessment Framework (2008) in particular. And, to varying degrees, they imply criteria for assessment—both for specific texts (e.g., link to other texts, use audio and visual as well as alphabetic text) and for other literacy skills, including evaluating texts and collaborating with others to create texts. What they don’t do, however, is provide full sets of criteria for assessing specific texts.

GENERAL GUIDELINES ON DIGITAL ASSESSMENT

Other recent publications aim to identify criteria, providing general guidance to teachers for the assessment of digital compositions. Three, in particular, show how assessment can follow from the broader position statements we just reviewed in the section above. The National Writing Projects’ Because Digital Writing Matters (2010) includes a review of five major policy statements, one of which is the NCTE Curriculum and Assessment Framework. Through this review, the authors identify areas of consensus on traits and actions expected of digital learners. Among these are the following broad areas: “creativity and originality,” “collaboration,” “diversity,” “communication in rhetorical contexts,” and “remix culture,” which includes “ethical use,” “participat[ing],” and “publish[ing]” (pp. 100–101). By identifying key points of consensus, this list helps narrow the focus for curriculum planning and assessment, although specific criteria for assessment are not identified. It is important to note that this list includes “diversity” (e.g., “cross-cultural understanding,” “diverse perspectives”) an area that is dropped out of some other documents.

Another NWP project aims to push toward more specific criteria for assessing digital writing. The NWP Multimodal Assessment Project Committee (2011) is developing an assessment framework that draws together some of the various composing skills and habits of mind identified in these broader frameworks. An April 2011 draft posted to the NWP Digital Is site identifies five domains for “assessing and improving our work as creators of multimodal texts”:

- Context: decisions about genre; “about where and how the communication enters the world”; also “Authors-designers-writers consider the constraints, affordances, and opportunities, given purpose, audience, composing environment, and delivery mode.”

- The Artifact: includes appropriate use of structure, medium, and technique

- Substance: “overall quality and significance of the ideas developed”

- Process management and technical skills, including collaboration

- Habits of mind: “creativity, persistence, risk-taking, mindfulness, and engagement.”(http://digitalis.nwp.org/resource/2751)

This framework is useful in delineating these broad domains for assessment. Notice that it is more encompassing than accepted assessment rubrics for finished texts, say the 6 + 1 Traits Rubric that focuses primarily on traits of “the artifact” (Ideas, Organization, Voice, Word Choice, Sentence Fluency, Conventions, and Presentation). Here, important rhetorical skills are included as well as process skills, including collaboration. The more elusive category for assessment is “habits of mind, ” which includes such traits as creativity and engagement. Although still a work in progress, this framework—like the NCTE Framework—is useful for identifying the range of skills and dispositions to consider in both instruction and assessment.

Another recent book, Troy Hicks’ The Digital Writing Workshop (2009), includes a chapter headed “Enabling Assessment over Time with Digital Writing Tools,” a chapter that builds a bridge between broad standard statements and classroom practice. As with other approaches, Hicks stresses the importance of linking assessment to composing skills and assessing both process and product. For product assessment, Hicks adapts the 6+1 Trait Rubric, showing how it could be developed to assess various sorts of digital compositions (e.g., wiki, digital story). In showing how traits would vary according to medium, Hicks stresses the following:

The ways in which I describe six traits for digital writing… are not meant to be a rubric in and of themselves per se; instead… I hope that they help inform you as you make decisions about how to adapt assessments that you might already be using to incorporate elements of digital writing and, moreover, consider the ways in which different media change the ways in which we conceive writing. (p. 114)

In other words, as teachers we need to look to our specific assignments and develop assessment criteria linked to those assignments, considering particularly how the media used affect the nature of the created text and, in turn, the assessment of that text. Hicks’ comment points to the value of seeing how specific teachers make these adaptations for specific digital assignments: What was the assignment? What were the teachers’ goals for their students’ learning? How did students work through the assigned project? And, how was their work assessed?

TWO TEACHERS’ DIGITAL ASSIGNMENTS

AND ASSESSMENTS

For fully contextualized examples of teachers’ assessment practices, we now turn to the work of two teachers and their assessment of two quite different and substantial digital projects, one a digital picture book and the other an online, discussion-based blogging project. Both examples show how these teachers intertwine standards for technology and digital writing, what the authors of Because Digital Writing Matters (2010) called the “double helix of writing and technology” (p. 93). Kevin Hodgson positions his students as artists and creators of books; Paul Allison positions his students as public bloggers and informed communicators engaging in online discussions with their peers about real topics that interest them. These two different writer–audience relations are crucial to each of these projects and, in turn, to the different ways in which their teachers assess the outcomes.

Kevin Hodgson’s Digital Science Picture Book Project

Our first example of teachers’ assessment of multimedia projects comes from Kevin Hodgson’s sixth-grade classroom in Southampton, Massachusetts. In this curriculum unit, Kevin scaffolds his students through the creation of digital picture books designed to explain scientific concepts. Students use slideshow-creation software for the project, and at the end of the unit present their work—and are critiqued by—third-grade students. As you will see, the project and its criteria align with the Common Core, in particular Writing Standard 6 for Grade 6: “use technology… to produce… writing as well as to… collaborate with others” (p. 43).

Kevin describes his goals for his students’ learning in the following words, taken from his presentation of this unit in his resource, “Bringing Digital Books to Life” (2010), on NWP’s Digital Is web site:

My inquiry stance has always revolved around putting the tools of composition into the hands of my young writers and creators, and while we use technology for this project, what my science teacher or math teacher colleagues and I are looking for is understanding of complex material told under the umbrella of a digital picture book. The technology engages them, for sure; but it is the crafting of story, the creation of artwork, and the strategies that go into publishing a digital book that forms the kernel of learning here. In some ways, it is a success when the technology becomes less visible, and the voice of the young writers and artists are what emerge from the work. (http://digitalis.nwp.org/resource/606)

As we take you through Kevin’s curriculum unit, paying particular attention to his systems for assessment, please note what we feel to be the generalizable, transferrable elements: a mix of summative and formative assessment; a mix of self-, peer-, and teacher assessment; criteria for assessment clearly presented at the beginning of the unit (the checklist); assessment that is ongoing throughout the 6-week project; and close alignment with state standards.

It will be helpful at this point that you get an overview of the project that Kevin has assigned his students. Assessment is to a great degree context-specific, and to understand Kevin’s assessment processes you’ll have to understand how they fit into, and arise from, the design of his project and his goals for student learning. We understand that this will be a break in the print narrative we are giving you, but we’ll be ready to welcome you back after you’ve finished, for a look at an actual student project. For an overview of this project, which Hodgson presented at the NCTE Annual Conference in 2009, go here.

**********

Welcome back! Now that you have an overview of Kevin’s project, we’ll turn to an actual piece of student work that was created within this curriculum unit. Kevin and his students transformed one of the picture books into a video describing the process of a cell’s mitosis with student narration. The video takes 4 minutes, and is well worth the visit. It will give you a sense of the student work being assessed and, because the video is narrated by the student authors, you will hear the voices of the students who have been involved in this project. You can access it here .

**********

Again, welcome back. Now we turn, as promised, to the focus of this chapter: assessment of digital writing. Assessment is woven into the fabric of this curriculum unit. Again, in Kevin Hodgson’s (2010) words:

The assessment of work in this project, which can take about four to six weeks to complete, is ongoing, with formative assessments, such as reflective writing and periodic survey check-ins, as well as a summative assessment that uses a rubric designed to guide the work from start to finish. Peer review of the emerging books takes place on a regular basis, and technology skills that are learned by one student are made visible and shared with others. I should note, too, that most of the elements of the project—from the planning right to the publication—are connected to our state curriculum frameworks. I'm hitting the expectations of our state and school district, with a digital flavor.

Kevin gives us this list of the assessment tools he uses on this project:

Some of the assessment tools I use include:

- Daily writing reflections. With these, students self-assess where they are with their project, where they are going next, and what help they may need. This writing then guides our conversations when I meet with them as they are working on their project. These are short pieces of writing that are not graded.

- Informal surveys (often done online). These allow me to gather overall information about perceptions and problems that may be arising across the classroom(s). Questions on these surveys might include reflections about writing elements and technology use.

- Summative assessment rubric. This is handed out at the very start of the project and referred to on a regular basis. The rubric guides students in their work and provides focal points, particularly as the crunch time of deadlines looms.

- A peer review sheet. This is filled out during part of our revision process.

- A checklist. This provides yet another framework for keeping students on-track. Most students keep this checklist by their side during the final weeks of the project.

- End-of-project reflective writing. In this, students reflect on the entire project, talking about what they are proud of and what they would have done differently next time, and then I ask them to offer me advice for making the project better for the next year's class.

You’ll note here the mix of modes of assessment: some self-assessment, some assessment by peers, and some summative assessment. We include the text of Kevin’s “Digital Science Book Checklist,” which is both self-assessment and a guide for what will be the summative assessment of the finished work. We note that in a post-project survey, 88% of the students said that they had used the checklist.

Names:_________________________________________

Digital Science Book Checklist

Cover:

Yes / No Interesting and eye-catching title and illustration

Yes / No Author and Illustrator’s name

Title Page:

Yes / No Dedication

Yes / No Names of author/illustrator

Yes / No Publication company, year and location

Story:

Yes / No Well developed beginning, middle, and end

Yes / No Proper spelling and grammar

Yes / No Proper use of the Theme of a Scientific Journey in the story

Yes / No Proper explanation of Mitosis in the story

Illustrations:

Yes / No Detailed illustrations that explain the story (no clip art allowed)

End Page:

Yes/No Hyperlinks to at least two websites that explain your science topic

Extras: (optional!)

______ End pages with hints of the story

______ Author /illustrator biographies

______ Other: _________________________________

Comments:

And finally we include the rubric for the summative assessment, which, as Kevin notes, he gives to students at the beginning of the project, to guide them as they move toward the completion of their digital books:

Multimedia Project : Digital Science Books

Student Name: __________________________________| category | 20 | 15 | 10 | 5 |

| Spelling and Grammar | There are no misspellings or grammatical errors. | There are three or fewer misspellings and/or mechanical errors. | There are four misspellings and/or grammatical errors. | There are more than 4 errors in spelling or grammar. |

| Book Presentation | The book demonstrates excellent use of font, color, graphics, effects, etc. to enhance the presentation. | The book makes good use of font, color, graphics, effects, etc. to enhance the presentation. |

The book makes use of font, color, graphics, effects, etc. but occasionally these detract from the presentation content. | There is some use of font, color, graphics, effects etc. but these often distract from the presentation content. |

| Scientific Concept | The story covers cell mitosis with details and all steps of mitosis are included. Subject knowledge is excellent. |

The story includes essential knowledge about mitosis. Subject knowledge appears to be good. | The story includes essential information about mitosis but there are 1-2 factual errors and/or some steps are missing. |

The content in the story is minimal OR there are several factual errors. There is very little information about mitosis. |

| Story Format | The journey story demonstrates a clear and interesting beginning, middle and ending. | The journey story has a beginning, middle and end but there are loose ends to the story. | The journey story is somewhat confusing to read, but there is evidence of a beginning, middle and end. |

There is no beginning, middle and end to the journey story. |

| Cover/Title Page | The book has an interesting title, illustration, dedication, publishing company and date. | The book is missing one piece of information from the cover and title pages. | The book is missing more than two pieces of information from the cover and title pages. | The book has no cover or title page. |

This rubric is extremely clear, and serves a number of functions: it defines the teacher’s goals for student learning; it presents those goals to the students at the beginning of the project; and it offers a clear framework for a final, summative assessment. Although it includes some of the traits listed in the 6+1 Rubric, it adapts these abstract traits to the specific genre of a digital picture book (e.g., “story format,” instead of the more vague category of “organization”).

The rubric is divided into five sections, each equally weighted. For this project and this teacher, this division and weighting answer some of the issues raised in the assignment and assessment of multimedia projects. The first section, “Spelling and Grammar,” makes it clear that the “basics” of standard academic English are being addressed in the course. The second, “Book Presentation,” focuses on technology, but only in the service of design. It rates the students’ demonstrated ability to integrate graphics and text in the multimedia presentation. The third, “Scientific Concept,” is the “writing-to-learn” piece of the project, and addresses the authors’ grasp of the concept of mitosis. The fourth, “Story Format,” brings us back to English again, and rates the author’s ability to create and sustain a narrative that engages the reader. The fifth and final category, “Cover/Title Page,” rates the author’s ability to understand and work within the conventions of the print book.

We note also that this project is face-to-face collaborative, a valued skill in both the NCTE Curriculum and Assessment Framework (2008) and Common Core (2010), although Kevin does not seem to assess this collaboration explicitly. Kevin’s criteria also embed aspects of the “story genre” and conventions of a book. In this regard, these criteria parallel the National Writing Project (2011) multimodal trait of context. These criteria also position the students as authors/designers, which ties them to the NCTE Curriculum and Assessment Framework’s (2008) “newer aspects of assessment of 21st century learning,” which include the “extent to which tools can make artists, musicians, and designers of students not traditionally considered talented in those fields.”

Kevin’s criteria leave room for teachers’ and students’ aesthetic and rhetorical judgment, which we see as both inevitable and good. What, for example, in the category “Book Presentation,” is “excellent use of font, color, graphics, effects, etc. to enhance the presentation”? This criterion may seem vague or unhelpful, but it ties aesthetic and rhetorical judgment to a particular context. The phrase links “excellent use” to “the presentation,” which implies that “excellent use” will be specific to the particular purposes and audiences of a given presentation. The criterion also leaves room for diverse “excellences” defined by different cultures and life experiences. Further, it places the responsibility on the teacher to work with students to define what “excellence” means in their context.

Paul Allison: “Be a Blogger”

Moving from Kevin Hodgson’s digital science book project to Paul Allison’s online, discussion-based blogging project feels to us like entering a new dimension. Although Kevin Hodgson’s project had a clear social aspect—students collaborated with their classmates, and published their work to third-grade schoolmates—at the end of the process there was still a defined, assessable product. In Allison’s blogging project the teacher asks students to jump into Web 2.0 and use its affordances to connect with others, both peers and information sources. Students freewrite their way toward inquiry projects that they deeply care about; they maintain accounts on Google Reader that create what Allison terms a “river of information” related to their inquiry; they use a blog-search program to find others blogging about their topic; and they recruit and help create a community of peers who read and respond to one another’s writings about their topic. There really is no “finished” product; as the blog grows during the semester, its entries are periodically sent to the teacher. For this kind of text, the 6+1 Traits Rubric is even less helpful as a starting point. Indeed, it may be an instance where traditional rubrics may work at cross-purposes with the digital genre being created.

To begin to understand this curriculum, it will be helpful to visit the Youth Voices web site, designed and maintained by a consortium of teachers connected to the National Writing Project and coordinated by Allison. The affordances offered students and teachers by this web site make Allison’s blogging project possible. We suggest that you now go to the Youth Voices web site. We will lead you through this complex site in this text document, so we suggest that you keep both this window and a second browser window open, as we will be toggling back and forth between the two.

If you click on the “About” tab at the Youth Voices home page, you will find a short history and a goal statement that is a necessary starting point for beginning to think about assessment. The teachers who have created Youth Voices identify two goals. The first—“to have students publish multi-media, well-crafted products”—is one that we are familiar with and one that we can relate to because it is a natural extrapolation from our experience with reading and grading student essays, which we also hope to be “well-crafted products.” The second, to have students “engage other young people in conversations about real topics that they see happening in the world” and to have them “immersed in lively, voiced give-and-take with their peers,” is a goal that is uniquely suited to the social networking made possible by Web 2.0. Both goals are central to both the NCTE Curriculum and Assessment Framework (2008) and to the Common Core (2010).

As teachers ourselves, we have always valued class discussion, as have English and writing departments generally, using the writing and interactive components of teaching as an argument for relatively small classes. In the early days of computerized classrooms, both of us experimented with classroom-based online discussions such as those made possible by the program Interchange. But both face-to-face and classroom-networked discussion are different in important ways from what is now possible: they are restricted to the members of the writing class. Through Youth Voices, which has in a sense domesticated Web 2.0 for our purposes, students can compose in multimedia, they can draw on the seemingly infinite resources available online, and they can connect with anyone who has Internet access.

To get a flavor of the discussions that students might engage in, please go back to the Youth Voices home page and note first the “featured discussions” section, then the “discussions with recent comments” section, and finally the five tabs that lead you to discussions in five “channels.” (We might ourselves have said “five categories,” but that would have been so Web 1.0!) On Youth Voices, communication and information are fluid, moving rivers that are temporarily constricted and that temporarily flow in channels. The defined channels are: Art, Music, and Photography; Literature and Inquiry; Local Knowledge/Global Attitude; Gaming and New Media; and Our Space (K–8). The discussions on this active site are constantly changing, so what we see on the site as we write this chapter will not be what you see as you read the chapter. But the discussions on the site as we write are representative, and tell us that there are a large number of discussions and that the range of these discussions is wide. There are—as of this writing—postings on Joshua Schenk’s book, Lincoln’s Melancholy; on remembering Pearl Harbor; on “Skinny Jeans”; and on “Playing piano back in my Freshman years,” with a link to a YouTube video.

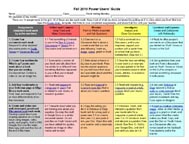

Now that you have a sense of the site available to Allison’s students, it is time to turn to Allison’s “Power User’s Guide” (2010) which serves, as Kevin Hodgson’s checklist did, both as a guide for students working on their blogs and related tasks and as an assessment tool for the teacher. This guide is available at the NWP Digital Is site. We reproduce it here as an image file, to provide a snapshot of the tool.

Figure 1. Screenshot of Accessment Tool from Digital Is

This initially daunting grid lays out the tasks that each student will perform each week over a 16-week semester. To support students in accomplishing these tasks, the site provides scaffolding in the form of teacher-written guides. These guides can be found on the “Guides” tab on the site’s home page.

For example, “Insert an image” is part of the weekly tasks outlined in blocks 1.2 and 4.4 of the Power Users’ grid. In the “Guides” section of the Youth Voices site, there is a guide titled “Finding Images Labeled for Reuse,” which leads students to three sources: Wikimedia; a piece of the huge Flickr image storehouse; and a way of using Google image search to find only public domain images. If a student’s task is to “respond to other students’ discussion posts on Youth Voices or Voices on the Gulf”—listed as the first of the weekly assignments on the Fall 2010 “Power User’s Guide”—you can find scaffolding for the task:

Dear <First Name of Poster> :

I <past tense verb showing emotion> your <post/poem/essay/letter/image...>, "<Exact Title>," because... <add 2 or 3 sentences>

One sentence you wrote that stands out for me is: "<Quote from message.>" I think this is <adjective> because... <add 1 or 2 sentences>

Another sentence that I <past tense verb> was: "<Quote from message>." This stood out for me because...

Your <post/poem/essay/letter/image...> reminds me of something that happened to me. One time... <Add 3 or 4 sentences telling your own story.> Thanks for your writing. I look forward to seeing what you write next, because... add 2 or 3 sentences explaining what will bring you back to see more about this person's thoughts. (http://www.youthvoices.net/node/23265)

The criteria for evaluating this task are embedded in the guide: the responder must use the “exact title” of the object of the response; the responder must find two sentences that “stand[s] out for me” and explain/develop this response; the responder must connect the post to their own experience; and the responder must make a personal connection with the author of the post being responded to.

The “Power Users’ Guide” does not directly speak of assessment. But assessment is definitely taking place in the progress of the semester. In his writing about a typical semester using this curriculum, Paul Allison stresses the value of students’ self- and peer-assessment. Periodically, students fill in a “How Am I Doing?” template, one of which we’ve copied in below from the Youth Voices web site:

How do you contribute to the Youth Voices community?

I contribute to the Youth Voices community by uploading my photos and posts featuring my ideas on my photography. By doing this, it lets other people on Youth Voices to access what I have written and comment on my ideas and what they think about it. I am also on a member of the Youth Voices group on Flickr which also helps spread ideas and share my photography with other people.

What is easy for you to do here?

Writing about my work and having discussions on it is easy for me because I know how I feel about my photography and what I want to do to improve. It is easy to share my ideas with everybody else and the message that I want to get across in my photography.

What is hard, but worth the struggle?

At times, Photoshop can be very hard and not go the way that you want it to go. But in the end, once you figure out what you're doing, it is definitely worth the struggle.

What do you wish you could do, but can't?

I wish that I could do more cool tricks on Photoshop (which I want to learn more about). (http://www.youthvoices.net/discussion/end-year-how-am-i-doing)

This self-assessment is connected to the social interaction built into the blogging process. As Allison has constructed this process, students must start their own discussions and respond to others’ blog posts. The nature and intensity of the responses they get to their online writing prompts an ongoing self-assessment. As Allison writes of his student Nichole, “it was the comments of other students to Nichole that mattered the most; these served as the real external assessment” (p. 79). And further, as Allison writes, “a student’s ability to assess his or her own work grows by constant exposure to models by students they know and students they don’t know” (2009, p. 80).

In the following passage, Allison describes the moment in the semester when the focus turns from teacher-assessment to self- and peer-assessment:

I always look forward to this change in dynamics, after which I begin to feel more like a waiter in a busy restaurant than a teacher in a school computer lab. No longer am I working to motivate students to do work for me. Instead, I am working to help each student to accomplish his or her own goals as readers and writers in a school-based social network. No longer am I assessing them; after the shift the students assess themselves, and decide what to do next. This shift, this turning point from teacher-centered to student-centered self-assessment, has come each semester since I put blogging in a social network at the center of my curriculum. (p. 79)

But finally there must be an assessment by the teacher. The “Power User’s Guide” lists a tremendous number of tasks, each of which must be completed in each of the 16 weeks. The tasks are, from the perspective of the “Power User’s Guide,” either done or not done. It would seem that the tasks are so specific and so many that if a student completed all the tasks each week for 16 weeks, the assessment would be relatively easy using two criteria: the number of tasks completed, and the extent or fullness of the completions. And here’s how Allison describes this assessment: “Although the school required me to report a grade for Nicole’s work every few weeks, I always de-emphasized the importance of my evaluation. I never grade specific blogs, and instead I keep track of the number of blogs and comments a student produced, giving higher grades for more and better-developed blogs and comments” (pp. 78–79). We note that there is not a final product to be graded here, but a text that evolves, a moving conversation. Assessing student participation in this curriculum is a challenge that Allison and his fellow teachers on Youth Voices have taken on directly, and, in our view, successfully.

CLOSING REFLECTIONS

So the question still remains: Where are we to find guidance in assessing this new, digital writing? We have examined four potential sources: tip sheets developed in and by industry; position papers and standards documents offered by professional societies and councils; recent resources offering general guidance on assessing digital writing; and full accounts by teachers of their situated practice. The first, the business-oriented tip sheets, offer advice about preparing presentations for groups of employees or potential consumers. These tip sheets suffer from two liabilities, for our purposes: they are highly abstract and they apply only to the finished product. The second, the position papers and standards documents we have examined, are much more useful to us as teachers, because they begin with curriculum and curricular goals that will drive our assessments. They go far beyond the judgment of the product, in the case of the NCTE 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment Framework (2008) giving value to collaboration, including a range of genres, and positioning students as writers and artists engaged in design as well as communication. The third, recent resources offering general guidance on digital assessment, help us bridge from the broad position statements to the classroom. These resources underscore the importance of assessing process as well as product, and the importance of adapting general criteria to meet the specific demands of a given rhetorical context, including medium and genre. In this way, they point to the fourth and clearly most useful source: full accounts by teachers of their situated practice.

In the teachers’ accounts we have drawn on from the Digital Is web site and from Teaching the New Writing (2009), we get as close as we can to the full context: the teachers’ goals for student learning; the ways in which the teacher has positioned students; the full particulars of the assignment; a good sense of the dynamics and character of the classroom, whether face-to-face or online; and, from the samples of student work given, a good sense of the characters and capacities of the students. Yet even in these detailed views of teacher practice it is still the case that we are exploring new territory. It is our hope, and prediction, that our knowledge of sound principles for writing instruction will stand us in good stead as we come to terms with writing assessment in the digital age.

![]()

REFERENCES

Allison, Paul. (2010, October 19). Power users’ guide. National Writing Project Digital Is. Retrieved from http://digitalis.nwp.org/resource/1134

Atwood, Jeff. (2007, August 16). Thirteen blog clichés. Retrieved from

http://www.codinghorror.com/blog/2007/08/thirteen-blog-cliches.html

Common Core State Standards Initiative. (2010, June 2). Common core state standards for English language arts & literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/assets/CCSSI_ELA%20Standards.pdf

Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, & National Writing Project. (2011). Framework for success in postsecondary writing. Retrieved from http://wpacouncil.org/files/framework-for-success-postsecondary-writing.pdf.

Herrington, Anne; Hodgson, Kevin; & Moran, Charles. (Eds.). (2009). Teaching the new writing: Technology, change, and assessment. New York: Teachers College Press.

Herrington, Anne, & Moran, Charles. (2010, October 20). Assessing multimedia compositions. National Writing Project Digital Is. Retrieved from http://digitalis.nwp.org/collection/assessing-multimedia-compositions

Hicks, Troy. (2009). The digital writing workshop. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hodgson, Kevin. (2010, July 31). Bringing digital books to life. National Writing Project Digital Is. Retrieved from http://digitalis.nwp.org/resource/606

National Council of Teachers of English. (2008, November 19). 21st Century curriculum and assessment framework. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/positions/statements/21stcentframework

National Writing Project with DeVoss, Dànielle Nicole; Eidman-Aadahl, Elyse; & Hicks, Troy. (2010). Because digital writing matters: Improving student writing in online and multimedia environments. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

National Writing Project Multimodal Assessment Project Committee. (2011). Multimodal Assessment Project. National Writing Project Digital Is. Retrieved from http://digitalis.nwp.org/resource/1577

Nielsen, Jacob. ( 2005, October 17). Weblog usability: The top ten design mistakes. Retrieved from http://www.useit.com/alertbox/weblogs.html

Reynolds, Garr. (n.d.). Top ten slide tips. Retrieved from http://www.garrreynolds.com/Presentation/slides.html

Sieber, Tina. (2009, May 23). 10 PowerPoint tips for preparing a professional presentation. Retrieved from

http://www.makeuseof.com/tag/10-tips-for-preparing-a-professional-presentation/

Tufte, Edward R. (1983). The visual display of quantitative information. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

![]()

Return to Top

![]()