Chapter 8

Composing, Networks, and Electronic Portfolios:

Notes toward a Theory of Assessing ePortfolios1

Kathleen Blake Yancey, Stephen J. McElroy, and Elizabeth Powers

Available as PDF

![]()

Dear Kathleen,

Are you satisfied with the current state of assessment at your institution or in

your program? Are you considering the use of ePortfolios to assess student

learning outcomes? Are you effectively using assessment data for improvement?

For over a decade, TaskStream has been working with colleges and universities

to support the successful management of institutional effectiveness

and accreditation needs.

INTRODUCTION

For over 30 years, portfolios—collections of texts that are subsets of a larger archive, contextualized through a student reflection (Yancey, 1999)—have provided compositionists with an assessment vehicle congruent with our curricula and pedagogy. Given that writing is a material practice, our first portfolios were print, modeled largely on the book, even if unintentionally (Yancey, 2004). Later, as electronic composing became more common, we began to incorporate electronic portfolios—also called digital portfolios and eportfolios—into our classroom practice, a practice that, like that of portfolios in print, we explored, documented, and researched. Early work in eportfolios, for example, included a special issue of Computers and Composition in 1996, a section of the Yancey and Irwin Weiser edited collection Situating Portfolios in 1997, and Greg Wickliff and Yancey’s “The Perils of Creating a Class Web Site” as well as the Cambridge, Yancey, and Khan volume Electronic Portfolios, both published in 2001. Later work has continued this trend and diversified it in terms of rhetorical situation: Miles Kimball’s (2002) textbook The Web Portfolio Guide, for example, speaks specifically to students; Yancey’s (2004) “Postmodernism,Palimpsest, and Portfolios” speaks to the differences between print and eportfolios; and the Cambridge and Yancey (2009) Electronic Portfolios 2.0 speaks to the institutional learning emerging from eportfolio practice across multiple disciplines and campuses.

Changes in the technology of text invariably trigger changes in the shape of text.

~Steve Bernhardt

Guided by the same mantra that characterizes print portfolios—collection, selection, and reflection—eportfolios have ranged from first-generation word-processed “print uploaded” versions to compositions created with later-generation and more capacious visual, audio, networked multimodal texts (Yancey, 2004). Interestingly, however, while there have been nascent efforts to create an assessment practice or methodology congruent with eportfolios (see, for example, Cambridge, 2010; Yancey, 2010), we have yet to create an assessment tailored to these new portfolios, in part perhaps because our energy has been dedicated to figuring out what this new genre was and what it might become, in part because, initially at least, assessing the new portfolios seemed to require but a minor adjustment, an extension of what was: a statement of outcomes, a scoring guide, careful reading. With new models of eportfolios now developed, however, and especially given the one we will highlight here—a comprehensive eportfolio keyed to writing and design created by Kristina, a graduate of our Editing, Writing, and Media major (EWM), with several different file types from a variety of programs, a well-designed hierarchical structure, and a unique presentation of self—we see the need for a new vocabulary, a new set of criteria, a new set of practices, and a new theory congruent with the affordances that eportfolios offer. Put another way, and as Darren Cambridge argued, eportfolios as they have evolved have also created a new exigence for assessment.

In responding to this exigence, we begin by defining the eportfolio as a composition (Yancey, 2004) operating inside multiple networks. Our evocation of network here links to Jeff Rice’s (2011) notion of networked assessment.

Networks, as Latour reminds us, are already there.

Our task is to trace them.

~Jeff Rice

Citing Bruno Latour’s construct of network, Rice advocated for a networked assessment keyed to tracing: for Latour, Rice observed, “tracing. . . is the process of describing. By describing as much of an observed activity as possible, patterns and connections not previously understood will be located” (p. 28). In this context, we describe the activities situating Kristina’s portfolio as a way of understanding the relationships—both inside the portfolio and outside it—through which writers and readers make meaning. Indeed, as we will see, we need this description for three reasons:

- first, before we can theorize an assessment for eportfolios, and as an aid to theorizing such an assessment, we need to read and review one eportfolio, at least, with some depth;

- second, such a reading allows us to describe what we see in the eportfolio in some detail, raising questions as we do; and

- third, on the basis of these two activities—which together allow us to understand and appreciate what such a portfolio offers—we can begin to theorize how such compositions might be assessed.

In other words, a tracing of a portfolio precedes any attempt at theorizing the assessment of such a text—at the individual, classroom, or program level.

Our purpose in this chapter, then, is to provide such a tracing, with attention to two specific dimensions of networked portfolios. One: we examine how the affordances themselves — the affordances of time, of the technologies available, of the Gestalt students want to accomplish, and of the range and number of artifacts available—impact the creation of the portfolio, create a network for the portfolio, and provide a vocabulary for tracing and assessment. Two: we consider how audience is amplified by the eportfolio: we consider what the “networks of context” for any eportfolio may be, and how including those explicitly affects the experience of creating the portfolio, of reading and reviewing it, and of assessing it. Not least, on the basis of these considerations, we make notes toward a new theory of assessment for electronic portfolios.

If you see something beckoning from another gallery, go for it. There are no wrong turns here.

~New York Times

Ways of Reading2

Taken together, the two lead articles in the May 1993 issue of College Composition and Communication forecast the issues we take up when we consider how we read electronic portfolios generally and how we read Kristina’s specifically: Steve Bernhardt’s “The Shape of Text to Come: The Texture of Print on Screens” and Liz Hamp-Lyons and Bill Condon’s “Questioning Assumptions about Portfolio-Based Assessment.” In his article, Bernhardt sought not to compare print and screen reading(s) so much as to “identify nine dimensions of variation that help map the differences between paper and on-screen text” (p. 151). These differences include what he calls nine on-screen tendencies: screen texts are situationally embedded; interactive; functionally mapped; modular; navigable; hierarchically embedded; spacious; graphically rich; and customizable and publishable. Given these screen characteristics and given that an eportfolio is displayed on a screen, reading it—with its interactivity and rich graphics, for example—is going to involve more than reading as we often conceive of the practice, at least in print. As Bernhardt suggests, “the presence of the text is heightened through the virtual reality of the screen world: readers become participants, control outcomes, and shape the text itself” (p. 154).

Portfolio-based writing assessment is materially and operationally different from previous kinds of assessment, and while we have so far established that portfolio ratings can operate within accepted assessment parameters, we have also established that portfolios help us answer questions that former methods cannot.

~Bill Condon

Reading portfolios, and in particular how raters read print portfolios, was the primary question Hamp-Lyons and Condon pursued: As they noted, “a great deal is still unknown about what portfolios do and, perhaps even more interestingly, about the nature of the role and activities we, as teachers and readers, engage in during portfolio assessment” (p. 176), a claim parallel to that we make today about digital portfolios. Condon and Hamp-Lyons inquired into the reading issue by asking their colleagues about the processes of reading a portfolio, designed in this case as a set of iterative readin gactivities: first, reading portfolios while keeping a reading log; and second, reading portfolios and then completing a “Reader Response Questionnaire.” What they found is keyed to five assumptions they determine to be problematic:

- Assumption One: Because a portfolio contains more texts than a timed essay examination, it provides more evidence and therefore a broader basis for judgment, making decisions easier.

- Assumption Two: A portfolio will contain texts of more than one genre, and multiple genres also lead to a broader basis for judgments, making decisions easier.

- Assumption Three: Portfolios will make process easier to see in a student’s writing and enable instructors to reward evidence of the ability to bring one’s own text significantly forward in quality.

- Assumption Four: Portfolio assessment allows pedagogical and curricular values to be taken into account.

- Assumption Five: Portfolio assessment aids in building consensus in assessment and in instruction.

What Hamp-Lyons and Condon found, of course, is that the reading of an assessment portfolio, like the reading of any text, is keyed to context—in this situation, to the assessment context they are investigating, which begs the question for us because our purpose is to not to assess a portfolio, but rather to design an assessment. We’re thus interested in exploring the more general reading processes that readers use to read a portfolio. Still, one finding produced in this study seems of particular relevance to ours:

We have found again and again in portfolios of different kinds, at different times, from different readers, a clear suggestion that readers do not attend equally to the entire portfolio. Although the portfolios in our study contain four texts from a course of instruction, each of which has the potential to offer conflicting evidence to the other three, readers’ self-reports indicate that readers arrived at a score during their reading of the first paper. A few readers reached a tentative score after the first or second paragraph of the first piece of text. Some readers postponed any decision until the second piece, but moved to a score rather soon within it. Readers seemed to go through a process of seeking a “center of gravity” and then read for confirmation or contradiction of that sense. (p. 182)

With an assessment as the context, it may be that readers “quit” once they have answered the central evaluation question, whether that be while reading the first text or a later one. How do we read, however, when our purpose is not to score, but to read; not to assess, but to understand the network of relationships an eportfolio stipulates and evidences through multimedia texts? Given this purpose, is there a point where we might we think we had read “enough?” And as important is our own experience with eportfolios because, we believe, that experience also contributes another context through which we will read any portfolio. All of us have taught with eportfolios, and one of us has extensive experience working with other institutions and their models of portfolios, but perhaps most important, all three of us have created our own eportfolios: Yancey as part of her teaching of a graduate class in composition theory in spring 2011, McElroy and Powers as part of completing the same course.

Kristina-as-eportfolio

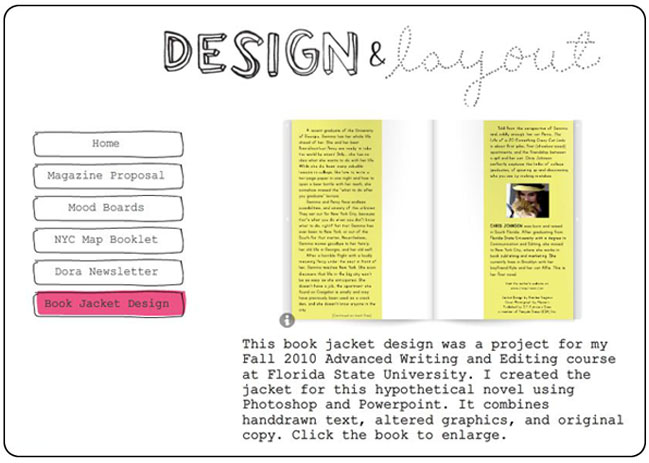

The portfolio that we engaged with is somewhat unusual, we concede: a comprehensive, self-sponsored electronic portfolio created by Kristina, a 2011 graduate of Florida State University’s new Editing, Writing, and Media major. It is not, in other words, an eportfolio created to earn a grade in a class or to assist with program assessment or even precisely to showcase a student’s potential as a prospective employee. With 56 separate entries—some from coursework, others from internships, and still others self-sponsored artifacts—the eportfolio includes work that “counted” for academic assessment as Kristina completed her major, to be sure, but the portfolio has as another purpose: self-representation.

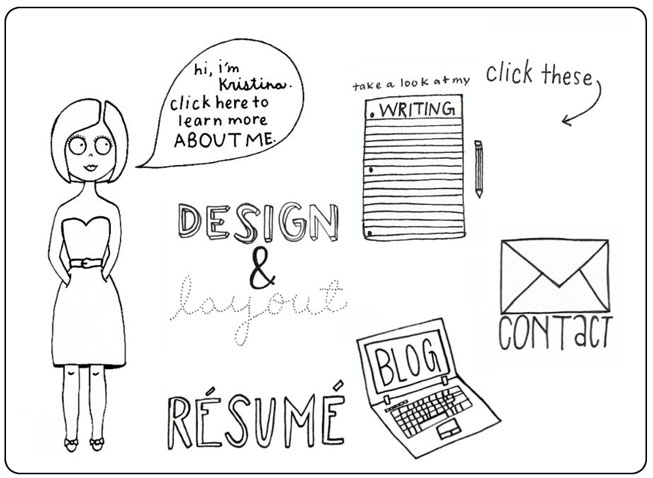

Figure 1. Portfolio Screenshot

Operating inside a hub and spokes model, the portfolio opens with a screen offering options for navigation laid out almost as figures on the face of the clock: there is no explicit verbal or visual signal as to exactly where one should commence reading. More specifically, the navigation options include six, perhaps the one most obviously pointing to a beginning—the “About Me” page introduced by an avatar for Kristina herself, which, like all the options, changes color when it’s clicked. The portal points as well to a contact page; a resume page; a blog page; a writing page; and a design and layout page. The first three of these—About Me, Contact, and Resume—each link to a single page: the About Me page briefly and graphically introduces Kristina. The contact link opens to a screen a reader can complete to send email; the resume page provides both the resume and the option of downloading the resume. The second set of three links points to pages that themselves offer a set of options: the blog to Kristina’s weblog; the writing link to a page listing four options, including a research assignment and a press release; and the design and layout link to a page listing five options, including a magazine proposal, a book jacket design, and a newsletter linking to a separate web page. As we began to read the portfolio, then, we had several options.

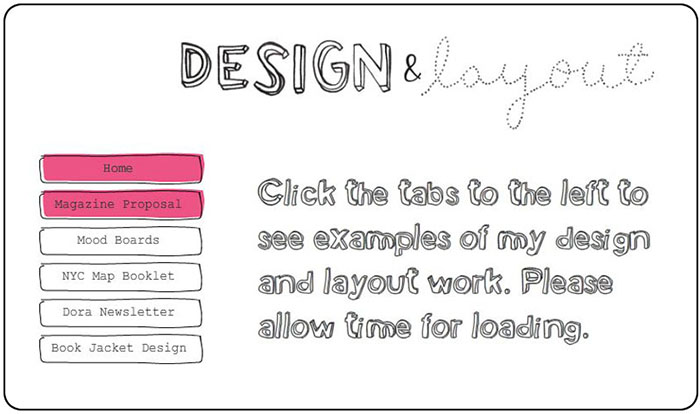

Figure 2. Portfolio Screenshot: interface

Put another way, although we began in the same place, what happened next was, as Bernhardt (1993) observed, idiosyncratic: “Out of many possible physical constructions of the text, the reader creates one, a particular chronological and experiential ordering of the text, a reading that belongs to no other reader” (p. 156). Thus, unlike the portfolio reading experience mapped by Hamp-Lyons and Condon’s (1993) colleagues, where readers read the same portfolio text in a specifically chronological order, we were on our own.

Reading Kristina’s eportfolio involved, first, making a set of choices, some of which were. . . well, to not read. Beginning to review the portfolio, we first decided, each of us separately, which page to click first, then which link to click second—an act that could simply have taken us back to the portal—then which link to click third, and so on. Upon encountering a text, we needed to decide what to do with it. Would we, for example, click the contact screen and complete the email form so that we were both reading and writing? Would we download print texts—which ranged from the one-page resume to the multi-page research project—to our computers and read those, and if so, would we read them through completely and carefully, or would we skim them, or would we, like Hamp-Lyons and Condon’s readers, quit in medias res? Would we link to a video and not read it, but rather watch it? Would we link to a separate web page and navigate it? In sum, if we engaged every textual option within the portfolio—that is, if we “read” the portfolio—we’d be engaging in many kinds of reading, in viewing, and possibly in writing as well. In addition, even the texts that were primarily alphabetic included a visual component, and the screen environment of the eportfolio encourages a reader to attend to that dimension of textuality consistently. Thus, we call the mixed set of reading practices an eportfolio invites, the practices that we engaged in ourselves, viewing/reading.

Viewing/Reading

We began our viewing/reading in five ways:

- individually, we viewed/read Kristina’s eportfolio, often taking notes;

- we compared our viewings/readings both in person and online;

- we mapped our “sense” of the eportfolio;

- we conducted a pin-up of the eportfolio; and

- we synthesized our notes.

Initially, we represented our reaction to the eportfolio as much by raising questions as by observing, as we see in this multivocal conversation:

Does the concept of eportfolios having “areas” unlike print portfolios (if that’s the case) matter (it would seem to me to, especially if multi-navigability is an important factor of web-sensibility), and do we have a good term for that? And maybe “style” plays an important part? Time as a critical dimension: *what difference does it make?

Time makes a difference because of the transience/shiftiness of internet spaces (i.e., Kristina and Stephen’s dead or inaccessible links (does mine have dead links?!). The portfolio—as a networked body—continues to materially shift/evolve/ decay while it’s still visible to readers in a way that print ports don’t. (maybe this is a “duh”—sorry!) *it is a duh, but only after you realize it :) because I think this is something that, while we rarely think about it, does have to be considered, especially the dead-links aspect (because print portfolios get lost/trashed/burned over time, too, but they are self-contained and independent).

Time seems much more fluid; more represented in the comprehensive port.

*Yes, the various possibilities for directing narration or “touring” the eportfolio offer a nebulous chronology. Also, the multimedia affordances of the eport provide a means of archiving a progression.

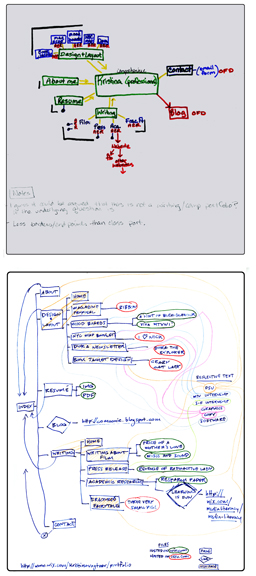

Through these “cascading” discussions—where we responded to, disagreed with, free-associated from, and built on each others’ viewings/readings—we became aware that through those viewings/readings, we might be constructing different portfolios. To pursue this possibility, Powers and McElroy mapped the portfolio they saw. Powers’ map took the portal as the portfolio center and showed a hub and spokes model with color-coded categories.

Figure 3. Example of color use

McElroy, whose background includes a degree in computer science, provided a map more sensitive to the tree structure that computer programmers create in designing a program. Also color coded, McElroy used shapes to show levels of hierarchy and noted some software types. Thus, what we saw through these maps was as much what we as viewer/readers project onto an eportfolio as what it brings to us, in the former situation (1) our experience as eportfolio creators, (2) our viewing/reading experience of this specific portfolio, and (3) other experiences that could help us make sense of what is still a new genre.

The Pin-up, the Synthesis

Aware that we were reading differentially and with only the question of how to assess—and not of what assessment to provide—governing the task, we also were also interested in how we understood the portfolio. In other words, when reading it, what in particular stood out? And how did we understand the component parts of the portfolio? Furthermore, how did we see—and seeing here is more description of viewing/reading than metaphor—the portfolio as a whole, as a composition?

Figure 4. Example of pinning up

Thus, motivated in part by our differences in reading and by an intuitive sense that we weren’t seeing the entire portfolio, we searched for another investigative technique that would allow us to trace in yet another way: what we are calling spatial reading. Yancey, recalling her experience with architectural pin-ups—an architectural review practice in which architects and students studying architecture (1) prepare visual material showing various dimensions of a given project, (2) tape it on a wall or other like surface, and (3) use that exhibit as both starting point and material for discussion—thought that adapting this approach for our purposes might be useful. We thus printed out each screen of the portfolio, including stills of animated screens, and pinned each one up on a wall so we could see (1) all the components in the portfolio; (2) the arrangement connecting them; and (3) the way the portfolio looked as an entire entity.

Visually, the pin-up functioned as a heuristic for us. On one level and quite simply, we had clusters of artifacts that we arranged on the wall. Immediately, though, we found that as we taped each screen shot to the wall, we had to keep moving the home page to accommodate the ecology Kristina had created. Quite simply, what we understood was that the design of the arrangement was much more sophisticated than we had realized. On another level, we saw a composer with a very rich set of composing practices. We had understood this before, but how rich those practices are became more evident with every screen we taped to the wall. On yet another level, we began to see patterns that had not been apparent to us through the perspective of the screen. For example, earlier we had failed to appreciate two dimensions of the web project on children’s programming that Kristina created. First, we hadn’t appreciated the extent of the project: it accounts for over half the screens in the portfolio. Second, and as important, given both the critical mass of the project and Kristina’s use of a rhetorical visual design keyed to children—with primary colors and kid-like graphics— we understood in this project Kristina’s enactment of a very different visual aesthetic than the personal one informing the rest of the portfolio; we thus saw as well the range of her rhetorical design practice. On yet another level and not least, we began to appreciate much more completely the arrangement of the eportfolio and the way it interacts with navigation: design and writing are separated, with the last item in the writing category—a remediated fractured fairy tale—operating at the intersection of both, functioning as something of a boundary object, which made sense because it represents a balance of word, image, and design.

Figure 5. Pinning up in action

But as important in this spatial reading of the portfolio was its embodied nature. As Bernhardt (1993) suggested, the reading of an electronic text is tactile in that to read, one clicks a mouse or touches a screen. But with a pin-up, we taped pages to a wall; we pointed to those pages; we touched them; we moved from one section of the portfolio to another as we read together, not in chorus so much as in collective, allowing both individual readings and mutual readings to operate concurrently and to inform each other.

Our synthesis, like our sharing of notes, began with an online discussion: Yancey had written notes to which McElroy and Powers replied.

Final thoughts (after the meeting):

- The eportfolio is an emerging genre; it’s both like and different than the print portfolio, and both of them participate in larger cultural understandings of portfolio (a point I made in Portfolios in the Writing Classroom, 1992). As an emerging genre, the eportfolio doesn’t yet have a defining set of conventions.

- We teachers make assignments, but often students animate those assignments, in the process giving definition to the new genre and helping us all understand what we value. * and when they do animate the assignments (nice term, btw), we value the students. :)

- The space that eportfolio inhabits is a new one, at least for school in that it’s not confined to school nor to the “official.” It is thus available for new texts and new practices and new understandings--and relationships across and among them.

- Some of the meaning of Kristina’s eportfolio comes from the visual, and a visual that is more than what the page offers (as important as that is). Is this a defining feature? Yes, maybe here is another point of tracing--between text and images. Agreed—definitely a defining feature.

- The repurposing of language while retaining it for more conventional uses (e.g., style); the continuation of traditional language (e.g., genre); and the development of a new vocabulary.

- What counts as writing?

a. And what counts as a writing portfolio? (And how much does that matter)?- At some level, our discussion is about meaning, about how it is made (in part through affordances, which are different, which is why we need a vocabulary), and how Kristina makes meaning of her education, her values, her experiences—all on a single site that interfaces other texts. Put differently, is there a network of meanings represented in her eportfolio, or is there a set of networks, whose layers provide resources for meaning-making: the role of “layers of meaning?”

Through this process, we began to identify the features highlighted in this tracing. What are the networks created within the portfolio? What are the networks that contextualize it? If the eportfolio is a composition, how is coherence created? What happens to audience in such a portfolio, and how might it be linked to coherence? (All questions we take up later.) But, surprisingly, we found that thereading of Kristina’s portfolio was neither as simple nor as transparent as we might have expected. We found ourselves theorizing a new kind of reading, viewing/reading, which bridges what in an eportfolio is not a dichotomy (between print and digital, between page and screen), but rather a set of continuous practices.

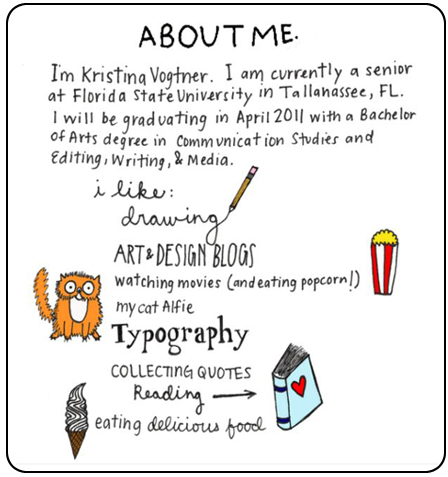

Figure 6. Book Jacket Design

Also, ironically, we found ourselves using paper to understand the complex nature of an electronic portfolio and its compositionality. Based on these experiences, we began to consider whether or not it is the case that there are multiple reading processes that one needs to engage in, particularly when a portfolio, like Kristina’s, is elaborate and complex. Is it the case, as well, that eportfolio viewers/readers might need special preparation for eportfolio viewing/reading if they are to understand what an eportfolio represents and how it can be a composition? In other words, to understand enough about eportfolios to view/read well—which is in part exactly what we are trying to determine, because to assess well, doesn’t one have to read well? All the “burden” in assessment is thus not on the composer: It’s a shared responsibility between composer and viewer/reader, and we as viewer/readers need to do our part. Likewise, does this doing our part entail engaging in multiple reading practices, as we did here, so that the portfolio viewer/reader—and the portfolio composer?—understands the conventions of this nascent genre?

Thinking toward assessment, then, we see the need to highlight three kinds of reading that portfolio composers and portfolio viewer/readers will want to consider. First, there’s the viewing/reading of each individual text—which itself involves different reading practices for different kinds of texts—print, static screen, animated multimedia (video files, academic “papers,” etc.). Second, there’s the reading of the portfolio on the screen, where basically one toggles from the reading of the screens and print files and animated files to the reading of the portfolio as a composition, and where in this toggling one constructs the portfolio one is viewing/reading. And third, there’s a spatial reading, which helps us understand the portfolio as a composition in practical, embodied, and theoretical ways.

Figure 7. Internship Page Screenshot

Intersections (or: It’s a Network, Baby! ;)

Kristina’s portfolio represents the intersection of who she is and what she has done, of herself and her past work. Implied in the metaphor of a network, in the oldest sense of the term, is that a series of threads come together and intersect one another to form the net. As we trace Kristina’s portfolio, describing it so that we may locate “patterns and connections not previously understood” (Rice, 2011, p. 28), we begin to see intersections of several different varieties, with different kinds of threads emerging.

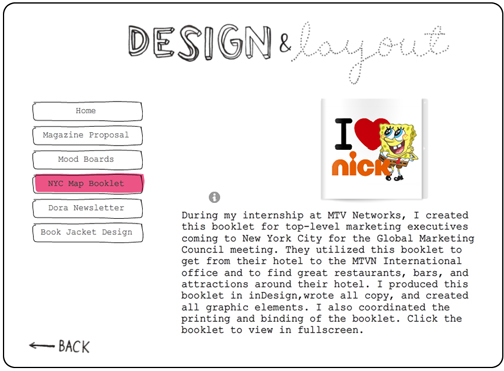

Figure 8. Krista's About Me page

The first and perhaps most obvious of these intersections is suggested by the electronic portfolio’s location: in the online network, namely at the intersection of complimentary computing technologies and Internet platforms. A second intersection is found in the portfolio: one constituted by the linkage between Kristina’s academic achievements, her professional pursuits, and her personal interests. A third intersection can be seen in Kristina’s arrangement of artifacts into two main categories: writing and design. Finally, the overarching intersection of the portfolio itself ties together Kristina and her work.

Thinking first about the networked technologies Kristina used, it is evident from the entry page that her production of the portfolio incorporated (on her end) at least two different applications. The linked, animated graphics on her home page (and those throughout the portfolio) are a result of Kristina’s composing in an unspecified graphics editor, and the site itself is designed in and hosted by Wix (an online web-creation and hosting service). Elsewhere, Kristina’s presentation of artifacts relies on networked technologies, particularly in the case of the artifacts in the Design & Layout section. For each artifact in that section, apart from the collages that she calls “Mood Boards,” Kristina uploaded her artifact to the web site Issuu.com (a third strand), copied the embed code for each of her documents from that site, and pasted it into an HTML widget on her portfolio. This intersection allows each document—such as the “NYC Map Booklet”—to be displayed and the pages of that document to be turned within her portfolio web page instead of as a download link. These are just two examples of technologies intersecting in Kristina’s portfolio.

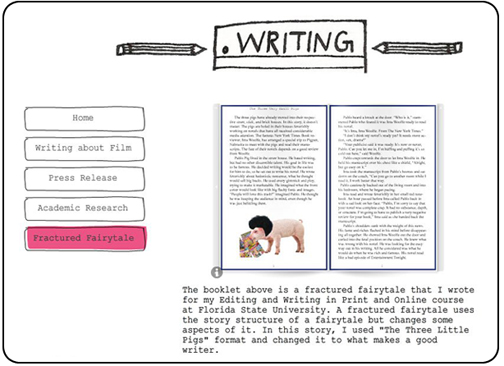

Figure 9. Krista's Writing Examples

While the intersecting technologies are a practical matter for the composition of her web site, the intersection of Kristina’s academic endeavors and her career interests are a conceptual one. As we trace these two conceptual threads, we see that Kristina also traced her own experiences in both arenas, selecting the artifacts from each that would best represent those experiences and that also were most appropriate for the electronic portfolio that she wanted to compose. In the Design & Layout section, she includes seven artifacts: four artifacts that she completed during her internship with MTV; one artifact from her Issues in Publishing class; and another from her Advanced Writing and Editing course. In the Writing section, she includes artifacts from three other classes and a press release that she wrote during a second internship with a fiction author. A third thread, her personal interests, emerges from the About Me page, where she articulates her interest in drawing—an interest evident across all the other sections of the portfolio in her page headings. Thinking toward assessment, we might wonder: How does Kristina’s seamless merging of in-school and out-of-school activities impact the viewer/ reader’s reception of her portfolio?

In addition to the intersection of school work and professional work, a second conceptual intersection is Kristina’s separation of her artifacts into two different fields of activity, “Writing” and “Design & Layout.” With these two navigational sections, Kristina explicitly divides her past work into separate categories. In the Writing section, Kristina showcases two essays on film, the fiction author’s press release, a research paper on children’s educational television, and a “fractured fairytale.” The introductory/reflective text for each of these artifacts features Kristina’s descriptive language in which she uses verbs such as write, study, interpret, delegate, edit, and collate, in contrast to the verbs used in the corresponding text in the Design & Layout section, verbs like create, develop, produce, and combine. Kristina uses words from this latter group to introduce texts that she sees constituting a different kind of activity than writing, although she again uses the word writing to describe how she created the “copy,” or alphabetic text, that appears in the designed artifacts—such as the “NYC Map Booklet” and “Dora Newsletter”—that she includes in this section.

Kristina also indicates implicitly that the processes she went through to create her presented texts are important to the exigence of the portfolio when she explains which software she used during those processes. For instance, she recounts specifically having used Adobe InDesign to produce the booklet, and she tells how she used Adobe Photoshop and Microsoft PowerPoint to create the book jacket. We may conclude that she sees her ability to use these programs as an asset, one that she feels the need to highlight. We may also deduce that Kristina conceives of design and layout as activities that necessarily involve or are dependent on computer programs in ways that writing does/is not. Although we know that such explanations exclude some information, it is easy for us to understand why Kristina does not say that for each artifact in the Writing section she used Microsoft Word to create it. Experience with word-processing software is not a particularly valuable asset in the way that work in those other programs is, at least not for Kristina, who appears with this portfolio to want to show us what is valuable in her technological repertoire.

As we trace strands across these two sections, the elaborate network that Kristina’s portfolio represents becomes evident.3 If we step back from those individual threads, however, we can also see how the portfolio as a whole represents the intersection of who Kristina is and what she has accomplished. In other words, she makes the portfolio her own, through graphics and headings she created as well as through choices of colors and aesthetics, so that the viewer/readers almost gets the sense that they actually know something about Kristina- the-person in addition to what they know about her past work.

Art museums are gradually becoming more flexible organisms. Increasingly they’re paying attention to connections rather than divisions among cultures. But visually making these connections in book format is difficult, particularly if the book is as unwieldy as this one. You can move through time and space only via ponderous page flips, whereas on the Internet, or an e-reader, this would be easily finessed: copy and paste, point and click.

The About Me section, for example, provides context for Kristina’s personal interests, and the aesthetic of the illustrations and typography there is carried throughout the rest of the site as well. Her inclusion of separate links from the home page to both her personal blog and her professional resume also illustrates the overlap that she established between her work and her personality. Thinking toward assessment, then, how much of a student do we want to see “there” in his/her portfolio?

Coherence in Print and Digital Texts

Both composers and viewer/readers seek coherence in electronic portfolios, as we do in all kinds of texts. In “Looking for Sources of Coherence in a Fragmented World,” Yancey (2004) explored—and compared—the various forms of coherence found in print and digital texts. She describes coherence as being about relationships: “Coherence is at the heart of print texts, of course, bringing into relationship arrangement and development, form and content, author and reader” (p. 90). Coherence is thus found in word-to-word and word-to-context relationships, linear organization, and text-to-page relationships. Such varieties of coherence are not unavailable to digital texts, of course, but the affordances of digital composition allow for additional modes of coherence. Yancey named the following: repetition, multiplicity of arrangement, linking, templates, and patterns. Such a wide variety of opportunities to create coherence can help a student create a sophisticated, strongly unified portfolio composition. Because of the plethora of texts and contexts that can be connected into a single eportfolio, coherence becomes an important way to make meaning. Here, two questions for assessment might be raised: (1) What methods of coherence are used to what affect? And (2) how successful are they at supporting the composer’s intent?4

Figure 10. Learning is Fun

Kristina’s Coherence

In her portfolio, Kristina establishes a strong base of digital features that contributes to coherence. Repetition is created because to progress through the eportfolio, the viewer/reader has to return “home.” Likewise, the home page, a repeated screen image that reminds viewer/readers where they are (Kristina’s portfolio), provides an anchor to the viewer’s/reader’s portfolio reading experience. The repeated viewing/reading of the home page in this hub-and-spokes model organizing the portfolio also contributes to another source of coherence: multiplicity of arrangement. Kristina’s portfolio home page thus provides a multiplicity of arrangement possibilities; the clustered arrangement of links on the home page mirror the rhizomic reading potential of digital compositions. Viewers/readers are encouraged to create their own paths through the portfolio materials—which puts some of the onus of creating coherence5 on the viewers/readers, as we will see.

The most striking feature of coherence in Kristina’s portfolio is a sort of doubled coherence. Although the Wix platform offers many possible templates, Kristina chose to build her pages from scratch. She designed lettering and illustrations for each portfolio section heading; these appear on her home page and repeat in modified form in each of the section pages. In essence, Kristina created her own template: the stylized lettering and images create a design unity located in her personalized aesthetic carried throughout almost the entire portfolio. But there is a second coherence as well, created by the segment of the portfolio where Kristina’s self-created template is absent. The Academic Research section of Kristina’s portfolio links to another web site she created, ”Learning is Fun,” which although included in Kristina’s portfolio, does not conform to the stylized design of the other pages.

Portfolios—especially electronic portfolios—provide a vehicle for the kinds of assessment we will need in order to design curricula for a student body that not only includes individuals from a wider and wider range of cultures, but also from a wider and wider range of ages and experience.

~Bill Condon

Instead, a differently stylized design, working from an aesthetic located in kid figures and primary colors, creates coherence within this text keyed to an audience of families with young children. The interplay of these two different aesthetic designs draws attention to the work that both of them do. This doubled coherence demonstrates Kristina’s design range, her ability to adapt, and her ability to create an aesthetic environment tailored to a rhetorical purpose in a way that would not have been evident had only a single aesthetic coherence had been present in the portfolio.

Coherence, Reflection, and Assessment

Even with Kristina’s doubled coherence, can we assess the success of such elements? Kristina’s portfolio does not include a reflective essay or cover letter, a component often considered imperative to portfolio assessment. Kristina makes a different choice. Her decision not to include a lengthy piece of reflection in her portfolio might be seen as a move of organic authenticity, a resistance to constructing a falsified image of what is there: because this portfolio is not a school portfolio, such a reflective piece might seem especially artificial. Still, the absence of a general reflection does not mean Kristina’s portfolio lacks reflection; it comes in smaller chunks as her annotations for each artifact discuss the context and purpose of the work. Although this type of reflection can cue us to the intent of the individual artifacts, there is no reflection on how the artifacts work together in the portfolio—such a question is left to the viewer/reader, aided by the elements of coherence throughout. That these reflective notes appear beside each artifact and not in a cumulative textual work is congruent with the rhizomic, fragmented qualities of Kristina’s digital portfolio. This leads us to two questions: Is it necessary—or how necessary is it?—to have a full or comprehensive reflective text in an eportfolio? How important is such a reflection for portfolio assessment?

Multiple Audiences, Multiple Paths

As mentioned above, Kristina does not include a general reflective text artifact in her portfolio, which may provide viewers/readers more opportunity to create their own paths through the portfolio. The lack of this kind of reflective text, which can have a directive function, also keeps the portfolio open for many audiences and many purposes. For example, a potential employer might navigate through Kristina’s work, presented in a format that is open but not overwhelming, to create his or her own overview of the potential employee’s interests and strengths. At the same time, Kristina does offer some direction for reading her portfolio. The materials she includes are hierarchically arranged through their different categories so that navigation can be informed: She creates paths for her viewer/readers, for example, by dividing her work into two separate categories: writing and design. All of the artifacts that she includes contain elements of both writing and design, but her use of the two categories affects how we look at the materials included under each section. For example, the “Learning is Fun” web site, an artifact whose importance has been discussed above because of its design aesthetic, is categorized under Writing/Academic Research. This categorization allows readers to view the web site in conjunction with a research paper on the effects of children’s television programming she co-authored in class. The “Learning is Fun” web site thus acts both as a supplement to, and in dialogue with, an academic writing project.

An additional method of hierarchal arrangement Kristina utilizes is embedding artifacts in various levels away from the home page. Rather than being all equally in reach, the artifacts are set up in a tiered system, allowing Kristina to demonstrate how she prioritizes the display of various artifacts for viewers/readers to find. For example, her resume is included as a category on the home page: This artifact is key professionally, one Kristina wants to make immediately available. In contrast, it takes seven clicks to get to Nick Jr. games, a link provided in an “additional resources” page on “Learning is Fun.” Such an artifact is not prioritized because it is not her own work—it merely provides context for and perhaps audience interest in children’s television programming. Thinking towards assessment, we might wonder: Does lack of explicit guidance provided by the portfolio composer through reflective material mean the portfolio composer yields more control to the viewer/reader, and thus to an assessor, regarding how the work might be read?

Figure 11.Ways to Read

Alternatively, does the plurality of gently guided paths provided by the composer prompt the viewer/reader to try to navigate the *best* possible path for him or her, perhaps in an acknowledgement that we all read differently? Do the directoverviews accompanying each artifact, rather than a single reflective letter, show a more sophisticated approach to a digital portfolio, one shedding the conventions of print portfolios?

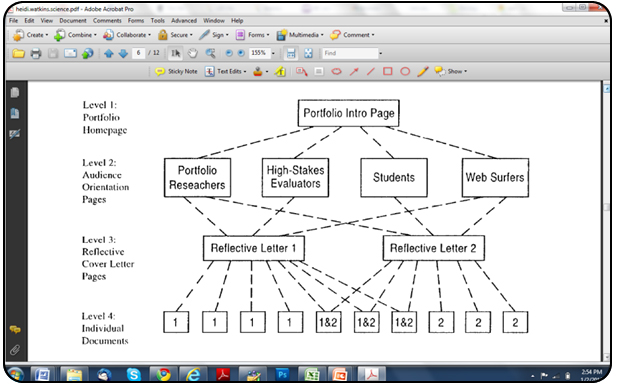

How we shed these conventions seems to be an issue still in process. In the 1990s, Steve Watkins addressed one of these conventions: how audience for a portfolio changes once it is on the web. Put as a question, how can one address multiple audiences? As Watkins (1996) explained in his Computers and Composition article (and as he showed in the diagram on the next page), accommodating audiences meant writing multiple cover letter-like reflections to preface his works differently for each audience; the single portfolio thus has smaller portfolios inside it. In contrast, Kristina chooses to limit her reflection, providing only basic context and purpose for each artifact, and such a “fragmented” reflection could be a challenge if the viewer/reader were using a traditional portfolio-reading approach. Still, one of the benefits of using portfolios is tapping the genre’s allowance for providing writing context: Rather than examining just a single written artifact, we can review a portfolio making available process and context as well as artifact. But these issues raise several questions: How much (and what kind) of context should be provided for a web audience? How can this context be balanced against the context to be provided for an assessor, which is presumably different from the context of a vernacular reader?What rhetorical moves—thinking here of addressing specific audiences—count as powerfully addressing audience, and what count as negatively limiting audience, ignoring the greater digital context in which the work is placed? Perhaps a successful portfolio—thinking toward assessment—lies more in showcasing ability to anticipate and satisfy multiple audience needs (like Kristina’s doubled coherence) than in pinpointing a targeted audience for reflection and display.

Web-sensible eportfolios

As we think about assessing an electronic portfolio, another question that we might have is about the extent to which the portfolio in question is necessarily electronic. In other words, is the portfolio “web- sensible?” In “Postmodernism, Palimpsest, and Portfolios: Theoretical Issues in the Representation of Student Work,” Yancey (2004) described three different kinds of electronic portfolios: an online assessment system, a print-uploaded model, and

what we might call “Web sensible,” one that through text boxes, hyperlinking, visuals, audio texts, and design elements not only inhabits the digital space and is distributed electronically but also exploits the medium. In other words, this model may include print texts, but it will include as well images and visuals, internal links from one text to another, external links that provide multiple contexts, and commentary and connections to the world outside the immediate portfolio…The medium, then, is media (p. 746).

Networks, as Latour reminds us, are already there.

Our task is to trace them.

~Jeff Rice

She goes on to suggest that the web-sensible model “offers at least two navigational paths” and that the author’s reflection guides viewers/readers through these paths.

If we look at Kristina’s portfolio for elements of web-sensibility, we can see them enacted throughout, starting with the home page. Here, the portfolio offers six navigational paths, each one represented by a hyperlinked graphic. In the upper-right corner, Kristina instructs the viewer to “click these,” referring to those links. She further addresses the reader with text embedded in the graphics for the About Me and Writing links, writing, “click here to learn more ABOUT ME” for the former and “take a look at my WRITING” for the latter. Elsewhere, within the two major, artifact-bearing Design & Layout and Writing sections, she provides instructions to “click the tabs to the left to see examples. . . Please allow time for loading.” As with the home page, the links in each of these sections offer different paths from which viewers/readers are free to choose.

In addition to offering various paths and providing instruction for the viewer, Kristina’s portfolio possesses other web-sensible elements defined by Yancey (2004), including the aforementioned graphics, animations, and “external links that provide multiple contexts” (p. 746). Two such links include the one to her blog from the home page and another to the “Learning is Fun” site that she developed in conjunction with her research project (under Writing). Other areas incorporate online display tools. Artifacts under Design & Layout, as discussed in the “Intersections” section, are embedded into the portfolio page through the use of Issuu.com. This subtly sophisticated employment of available tools creates a more sustained environment in which viewers/readers operate. By allowing the reader to scroll through the animated pages of the artifact without having to download a file or even leave the browser window, Kristina maximizes viewer/reader attention and simultaneously demonstrates her technical talent.

Thinking toward assessment, then, we might wonder: Given the variance of technical talent across populations and individuals, how much sensibility should be evident in a “web-sensible” portfolio?

The Take-away

When teachers and scholars migrated to print portfolios, the intent was to bring into a new relationship context, process, and product—in part to teach (Yancey, 1992), in part to assess (Elbow & Belanoff, 1991). Today we are migrating to electronic portfolios, in part to teach; in part to assess; in part, definitely, to evoke and then represent a new set of relationships—and in part, that’s been the intent of our chapter. In the context of the influence of the screen and of a desire to design an assessment that would be specific to and congruent with the texts of an electronic portfolio, we needed to develop a new vocabulary and a new set of practices: viewing/reading; the mapping of representations; spatial, embodied and collective pin-up reading. In particular, we theorized a viewing/reading that bridges what some theorists see as a dichotomy between page and screen, between print and digital reading practices; ironically, we called upon paper to help us understand the complex nature of an electronic portfolio and its compositionality. In our maps, we saw how we project our own assumptions and ways of reading and sense-making onto any text—but perhaps especially an eportfolio, whose conventions are still in process of definition—such that without some corrective, the portfolio becomes more unconscious mirror than text-in-dialogue. Through our collective reading of a pin-up iteration of this eportfolio, we developed a Gestalt for the portfolio seemingly impossible to acquire through the screen—regardless of how many windows we have open. The windows, of course, fragment, while the pin up, which (admittedly) is (yet) another mediation, expresses the whole composition in a single view. Based on our experience, we think that to understand what’s possible in an electronic portfolio, especially given its development as an emerging genre, those interested in assessing eportfolios should first engage in all three activities—(1) viewing/reading; (2) mapping representations; and (3) spatial, embodied, and collective pin-up reading.

In addition, our tracings produced several questions and identified areas for consideration; they motivate our notes toward assessment of electronic portfolios:

- The Role of Personalization. The personalization in Kristina’s portfolio augments the portfolio’s intersections, creating organic links between her academic achievements, professional pursuits, and personal interests. She creates her own graphics and headings, unifying her portfolio aesthetically; the result is that while we see different categories of work, we see them through a unified aesthetic; we thus see a fuller composition. At the same time, we wonder: What does such an aesthetic contribute to our reading experience? Does such personalization *ground* the portfolio in a way, even as different viewers/readers create their experience of the portfolio, with the result that we experience a concurrent doubled reading? Of course, such personalization, given that “beauty” is often in the eye of the beholder, can be diverting, and is likely to be especially so in cases where the aesthetic isn’t rhetorical in nature. The rhetorical end of the aesthetic matters. Thus, given the personalization we see in Kristina’s portfolio and the potential for such personalization, we wonder how personalized should eportfolios be. Put differently, what guidelines do we provide tostudents on this issue? Because of the plethora of texts and contexts that can be connected into a single eportfolio, coherence becomes an important way to make meaning. Here we saw many methods used together: words and images, repetition and aesthetics. Moreover, the interplay of two different aesthetic designs drew attention to the work both of them do. This doubled coherence demonstrates Kristina’s design range, her ability to adapt, and her ability to create an aesthetic environment tailored to rhetorical purpose in a way that would not have been possible had only a single aesthetic coherence been present in the portfolio. More generally, then, the issue of coherence is raised: what methods of coherence are used and to what affect? And how successful are they at supporting the composer’s intent?

- The Role of Coherence and the Means of Achieving It. Because of the plethora of texts and contexts that can be connected into a single eportfolio, coherence is required for the eportfolio to be understood as a composition. In the case of Kristina’s eportfolio, we saw many methods used together: words and images, repetition and aesthetics—all operating within a sophisticated navigational structure relating texts to texts, texts to contexts, contexts to contexts. Moreover, the interplay of two different aesthetic designs drew attention to the rhetorical work each of them accomplishes. This doubled coherence demonstrates Kristina’s design range, her ability to adapt, and her facility in creating an aesthetic environment tailored to rhetorical purpose. More generally, the issue of coherence is raised: What methods of coherence does an eportfolio composer design and to what affect? And how successfully do these methods enact the composer’s intent? How much (and what kind) of context should be provided for a web audience? How can this context be balanced against the context to be provided for an assessor, which is presumably different from the context of a vernacular reader? What rhetorical moves—thinking here specifically of addressing specific audiences—count as powerfully addressing audience and what count as negatively limiting audience, ignoring the greater digital context in which the work is placed? (Perhaps a successful portfolio—thinking toward assessment—lies more in showcasingability to anticipate and satisfy multiple audience needs rather than pinpointing a targeted audience for reflection and display.)

- The Definition and Role of Reflection and Its Role in the Portfolio. What is the role of reflection in an eportfolio? Is it necessary—or how necessary is it?—to have a full or comprehensive reflective text in an eportfolio? Does an absence of explicit commentary provided by the portfolio composer through reflective material mean the portfolio composer yields more control to the viewer/reader, and thus to an assessor, regarding how the work might be read? Alternatively, does what we have called the plurality of gently guided paths provided by the composer prompt the viewer/reader to try to navigate the *best* possible path for him and her, perhaps in an enacted acknowledgement that we all read differently? Do the annotations accompanying each artifact, rather than a single reflective letter, show a more sophisticated approach to a digital portfolio, one that sheds the conventions of print portfolios and at the same time shows us how different portfolios are being conventionalized? If the reflection in enacted, why would we need a verbal account? And is such a subtle approach especially appropriate in a non-scholastic portfolio? As we go forward, is it possible that, having created portfolios in both platforms—print and networked electronic—will we bring the conventions of one to the other, and what would this mean for reading practices and for assessment?

- The Role of Context and Assessment. How much (and what kind) of context or contexts should be provided for a web audience who isn’t formally assessing? How can this context be balanced against the context to be provided for an assessor—who, as indicated above, may “need” a comprehensive reflective text as another kind of evidence providing a basis for a specific kind of judgment—which is presumably different from the context for a vernacular reader? What rhetorical moves—thinking here specifically of addressing particular audiences and expectations—count as powerfully addressing audience and what count as negatively limiting audience, ignoring the greater digitally networked contexts in which the work is placed? Perhaps a successful portfolio—thinking toward assessment—lies more inshowcasing ability to anticipate and satisfy multiple audience needs rather than pinpointing a targeted audience for reflection and display. Display, in the sense of performing for others—as Mr. Bennet says to Jane in Pride and Prejudice: “Neither of us performs well for others”—seems to be part of an assessment mandate or scheme rather than an inherent feature of compositions or even portfolios. Likewise, there is a line of research, small but growing, suggesting that asking students to perform in this sense (as “proving” they have learned) might in fact be counterproductive because in such a context, ironically, they can be required to dissemble in order to succeed, with the result that portfolio-as-site-for authentic-assessment becomes another platform for the game of grades. In other words, are we here setting out criteria for very different kinds of portfolios?

- The Role of the Web-Sensible. Not least, given the variance of technical talent across populations and individuals, how much sensibility should be evident in a “web-sensible” portfolio? Is there a set of baseline criteria for being web-sensible? If so, what might those criteria be? And given the current commitment (or lack of) to our educational institutions and our increasingly diverse students, how much can and should we expect? How important is it that students learn to create networks and locate their own work inside networks, and to create hierarchies so that material is easily available? (What do they learn in such processes?) Given increased interest in coding-as-composing, what is the use value of mark-up languages (HTML, CSS) versus the use of WYSIWYG platforms like Wix? In other words, does writing/manipulating source code demonstrate web sensibility? To whom? Does it matter? By the same logic, does using a template in a WYSIWYG platform demonstrate less web sensibility than creating one’s own layout, link structure, graphics, color scheme, etc.? To whom?

In sum, we believe that eportfolio assessment requires a new vocabulary and a new set of practices, some of which we identify and model here. Likewise, after working with Kristina’s portfolio, and given the questions we have about reflection and navigation, it seems evident to us that eportfolios should be approached on their own terms. In other words, the framework we use to view/read and the vocabulary we use to talk about and assess eportfolios should, at least in part, emerge from the portfolios themselves.

Our discussion here is one effort toward that end.

![]()

NOTES

1. We have designed the pages of our chapter to appear as web-browser windows both as an acknowledgement of our content’s relationship with electronic spaces and as an invitation to our readers to recognize their additional position as viewers of our otherwise familiarly linear text.↩

2. How people read, generally, has been the subject of much attention lately, in part because of interest linked to book culture, but probably more relevant here, in part because of the influence of the screen on how we read. As explained by Megan Fitzgibbons (2008) in “Implications of Hypertext Theory for the Reading, Organization, and Retrieval of Information,” the utopian claims for screen reading, particularly hypertextual reading, relied on a seamless dichotomy between print and screen:

Amongst scholars, hypertext is difficult-or even controversial-to define. Theorists Landow and Delany (1991), for example, offer a rather loaded definition of hypertext, describing it as “the use of the computer to transcend the linear, bounded and fixed qualities of the traditional written text” (p. 3).

More recently, however, as Fitzgibbons observed, reading theorists have taken a more “nuanced” approach like the one put forward by Craine and Mylonas:

“’hypertext’ refers to the electronic linking of blocks of text” (p. 219). This definition high- lights the key property of hypertext, namely its capacity to create conceptual and literal links among disparate sections of a given text or among completely separate texts.

What hypertext offers, in this view, is a set of paths through which a reader creates a text’s arrangement, precisely what we see here in our experience with Kristina’s portfolio. But such a reading, guided by reader-identified paths, isn’t medium-dependent or determined; moreover, it’s a central issue in the assessment of portfolios regardless of medium. In the mid-1990s, for instance, this issue of how one reads a print portfolio raised the same issues, in part because how we read portfolios isn’t quite as simple or straightforward as Hamp-Lyons and Condon (1993) suggested. Allen, Sommers, Yancey, and Frick (1997) identified this issue when they conducted an external peer review of program portfolios, noting how two different readers read—not as a medium might recommend, but rather as they saw fit: “Kathleen characterized her reading of the portfolios as having what she called a ‘kind of cascade effect.’ By focusing on the attributes across the portfolio, she developed an overall impression of what she read. Jeff read differently, separating each individual piece of the portfolio from the others, attempting to suspend judgment” (p. 71). In fact, the reading processes employed by these readers engaged in reading and rating print portfolios, the researchers concluded, was “hypertextual”:

If we see the portfolio as text, then the most important positions are the first and last. But the relationship between arrangement and weighting [that is, the percentage that each component “counts”] assumes that readers will follow the prescribed order. As Jeff noted, he reads hypertextually: he chooses to read the reflection first, regardless of where it is placed. Do other readers read in their own hypertextual ways? And if so, (how) might this account for different readings of the same portfolio? (79)

A question we take up here, in the next section. Although, as indicated earlier, the complexity of the network can be approached and understood in several different ways.↩

3. These questions extend Yancey’s (2004) heuristic for digital text assessment: “What arrangements are possible? Who arranges? What is the intent? What is the fit between the intent and the effect” (p. 96)↩

4. The question of whether coherence is in the text or created by the reader has been taken up by others (e.g., Witte & Faigley, 1981). Here, we work from the assumption that both a text and a reader can contribute to creating coherence.↩

5.Not all artifacts are so accessed: Kristina’s portfolio does contain download links for some artifacts.↩

![]()

REFERENCES

Bernhardt, Stephen A. (1993). The shape of text to come: The texture of print on screens.College Composition and Communication, 44 (2), 151–175.

Cambridge, Barbara; Blake Yancey, Kathleen; & Kahn, Susan. (Eds.). (2001). Electronic Port- folios: Emerging practices in student, faculty and institutional learning. Washington, D.C.: American Association of Higher Education, 2001.

Cambridge, Darren. (2010). Eportfolios for lifelong learning and assessment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cambridge, Darren; Cambridge, Barbara L.; & Blake Yancey, Kathleen. (Eds.). Electronic portfo- lios 2.0: Emergent research on implementation and impact. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Condon, William. (2012). The future history of portfolio-based writing assessment: A cautionary tale. In Elliott Norbert & Les Perelman (Eds.), Writing assessment in the 21st century: Essays in honor of Edward M. White. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Elbow, Peter, & Belanoff, Pat. (1991). State University of New York at Stony Brook portfolio- based evaluation program. In Pat Belanoff & Marcia Dickson (Eds.), Portfolios: Process and Product (pp. 3–16). Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Fitzgibbons, Megan. (2008). Implications of hypertext theory for the reading, organization, and retrieval of information. Library Philosophy and Practice 2008. Retrieved from http://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/~mbolin/fitzgibbons.htm

Hamp-Lyons, Liz, & Condon, William. (1993). Questioning assumptions about portfolio-based assessment. College Composition and Communication, 44, 176–190.

Kimball, Miles. (2002). The web portfolio guide: Creating electronic Portfolios for the web. New York: Longman.

Rice, Jeff. (2011). Networked assessment. Computers and Composition, 28, 28–39.

Watkins, Steve. (1996). World Wide Web authoring in the portfolio-assessed, (inter)networked composition course. Computers and Composition, 13, 219–230.Witte, Stephen P., & Faigley, Lester. (1981). Coherence, cohesion, and writing quality. College Composition and Communication, 32, 189–204.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (Ed.). (1992). Portfolios in the writing classroom. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (1999). Looking back as we look forward: Historicizing writing assessment. College Composition and Communication, 60, 483–504.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2004). Looking for sources of coherence in a fragmented world: Notes toward a new assessment design. Computers and Composition, 21, 89–102.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2004). Postmodernism, palimpsest, and portfolios: Theoretical issues in the representation of student work. College Composition and Communication, 55, 738–761.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2010). Electronic portfolios and writing assessment: A work in progress. In Marie C. Paretti & Katrina Powell (Eds.), Assessment in writing. Tallahassee, FL: Association of Insti- tutional Research.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, & Weiser, Irwin. (Eds.). (1997). Situating portfolios: Four perspectives. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, & Wickliff, Greg. (2001). The perils of creating a class web site: “It was the best of times, it was the. . .” Computers and Composition, 18, 177–186.

![]()

Return to Top

![]()