Chapter 12

Assessing Learning in Redesigned Online First-Year Composition Courses

Tiffany Bourelle, Sherry Rankins-Robertson, Andrew Bourelle, Duane Roen

![]()

ABSTRACT

To deal with approximately $200 million in budget cuts during a 3-year period, the provost of our large public university (more than 73,000 students) challenged colleges and departments to develop approaches to teaching and learning that met the following three criteria: (1) reduce costs, (2) maintain or enhance student learning, and (3) maintain or reduce faculty workloads. In response, colleagues in the School of Letters and Sciences worked collaboratively to redesign first-year composition courses—our first-semester ENG 101 and our second-semester ENG 102—to accommodate a large number of students in a fully online environment where teachers work as a team to collectively facilitate and assess student learning. In this chapter, we describe the redesigned model and discuss its emphasis on multimodal instruction and learner-centered pedagogy. Additionally, we discuss the assessment of student eportfolios, an assessment framed by the Council of Writing Program Administrators outcomes statement.

![]()

The action in the learner-centered classroom features the students. (Weimer, 2002, p. xviii).

THE EXIGENCY OF WRITERS’ STUDIO

To deal with approximately $200 million in permanent cuts in state appropriations at Arizona State University (ASU), the provost challenged colleges and departments to develop approaches to teaching and learning that (1) reduced costs, (2) maintained or enhanced student learning, and (3) didn’t increase faculty workloads. After discussing a range of possible models with colleagues across the university, writing faculty in the School of Letters and Sciences redesigned two first-year composition courses—our first-semester ENG 101 and our second-semester ENG 102. The redesign moved courses from one teacher managing 25 students to a course shell with as many as 150 students instructed by as many as six teachers. To meet the provost’s criteria, these courses accommodate students in an online environment where teachers collaboratively facilitate and assess student work—thus enhancing student learning. Further, moving the curriculum online made the courses available to a wider range of students, as our institution has four campuses and an online program.

In this chapter, we describe the redesigned model with focus on the hallmarks of the course: post-process pedagogy, learner-centered pedagogy, multimodal instruction, and eportfolios that showcase self-assessment in response to the course learning outcomes, which are based on two disciplinary documents: the Council of Writing Program Administrators (2000) “Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition” (WPA OS) and the “Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing” (2011, produced by the WPA Council, the National Council of Teachers of English, and the National Writing Project). We will share the specifics of the online curricula we developed: Writers’ Studio. In doing so, we hope to encourage scholarly conversations about how alternative models for first-year composition such as the one we developed can be launched, updated, changed, and ultimately improved.

THE INSTRUCTIONAL TEAM MEMBERS

While designing the curriculum for the Writers’ Studio courses, an instructional team structured a post-process and rhetorically focused curriculum that incorporates learner-centered pedagogy and portfolio assessment. The course offers a “studio” model that requires students to produce no fewer than four drafts for each of the multimodal writing projects. Additionally, students interact in cohorts of 20 students within a course shell, with as many as 150 students enrolled in the section; this allows student access to a much larger writing community while engagement is also available within a smaller community. These courses are offered in both 15- and 7.5-week online terms. To successfully pass the class, a student must demonstrate understanding, with evidence from the WPA OS and the habits of mind from the “Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing” (WPA, NCTE, & NWP, 2011) Once a student eportfolio effectively demonstrates course learning, the student has completed the course. In principle, students could finish the course in a more accelerated time period; however, in practice, most students use the full term.

A team of faculty collaboratively designed the curriculum, which is consistent across sections of a course (e.g., ENG 101). Each course has a coordinator who oversees the curriculum and manages not only instructional activities, but also all instructional support within the course. Course coordinators are full-time, non-tenured faculty members holding the rank of lecturer or instructor. They work with multiple instructors and a group of instructional assistants (IAs) who collaboratively teach within one online course shell. Instructors within the course shell are contingent faculty, both part-time and full-time, who support the instruction of the courses. Faculty are assigned to work within the course based on the number of students enrolled. Once student enrollment exceeds the course coordinator’s course load, additional faculty members are assigned to a course to ensure student–teacher ratios are feasible workloads. Instructional assistants (IAs) are typically upper-division and graduate-level Education and English students. Instructional assistants, who act as peer mentors to students by providing feedback on student projects, are assigned to writing cohorts. All members of the team work closely together to facilitate instruction and provide feedback. In addition, students can receive feedback from tutors, typically campus writing center tutors, who are provided training on responding to the multimodal projects. This collaborative teaching model not only encourages student development, but it also allows for decreased instructional costs because individual course sections with only a few students do not exist. Furthermore, with the use of instructional assistants and multiple teachers, workloads have been decreased.

Advancing Learning with Peer-Mentors

A valuable asset to our course model is the use of instructional assistants (IAs), who provide feedback and direction on revised drafts. Instructional assistants are concurrently enrolled in a semester-long internship, comparable to a teaching assistant practicum, with the content of the course focusing on composition theories, specifically on facilitative feedback and peer tutoring. Before the start of the semester, IAs participate in two training orientations led by the Writers’ Studio teaching team. In the first orientation, IAs learn about the specifics of Writers’ Studio courses, including the layout of the course material and their responsibilities within the course, and they also become familiar with responding to multimodal projects by discussing several sample student projects. The second orientation familiarizes IAs with the use of portfolios as an assessment tool, and they participate in several workshops discussing learning outcomes, grading rubrics, and student examples, with emphasis on providing feedback to student portfolios. Throughout the semester, IAs frequently meet with lead teachers to review assignment details and receive further information on responding to multimodal projects.

Before the start of the semester, the IAs are integrated into the course not only to offset teacher workload, but also to provide a comfortable venue for students to receive feedback from advanced peer tutors. Within the internship course, IAs learn the importance of peer feedback and mentoring, as well as strategies for establishing rapport between themselves and the first-year writing students. Scholars such as Kenneth Bruffee (1984) and Muriel Harris (1988) noted the benefits of peer tutoring, including the development of internalized speech that manifests itself though writing as a result of collaboration among peers. Thus, to start the internship, the IAs first learn about the importance of peer feedback as a way to help students internalize revision comments.

Instructional assistants also learn to focus on higher-order concerns before addressing grammar and punctuation, as supported by Paula Gillespie and Neal Lerner (2003), who advocated that peer tutors first review higher-order concerns in the text before moving on to the local errors, including thesis development, support for arguments, and critical thinking. Gillespie and Lerner also suggested reviewing for surface errors that might signify larger issues within a project, keeping in mind that these surface-level errors can be indicative of other problems within the text. Learning to provide substantial feedback in the form of a “conversation,” IAs read theory regarding facilitative question-asking. As suggested by Richard Straub (1999), successful feedback is facilitative rather than directive; instead of appropriating a student text, feedback should encourage reflection rather than dictate revision. In addition to providing feedback on drafts, IAs engage in question-asking dialogue with students in online discussion boards and hold online office hours (via Skype) and on-campus meetings to facilitate conversations about student writing.

Engaging in Collaborative Course Design and Learner-centered Practice

All aspects of the courses, from initial design through student feedback, are collaborative. Interaction is an integral part of learning (Vygotsky, 1978), not only for students, but for an instructional team as well. Working together to develop and teach the courses provides extended opportunities to analyze instructional content and to recognize potential between content and instructional activities. In turn, during the teaching process, instructors mentor each other—sharing concerns and discussing problems. This collaborative process translates to the work that the instructional assistants perform, reading and responding to student texts, identifying issues in writing, working with students to make improvements, and providing mentorship throughout the semester. In addition, the collaborative teaching that occurs in the course also models active learning and peer-to-peer interaction for students.

The first-year composition curriculum described here is not only collaborative, but also reflects learner-centered practices. Maryellen Weimer (2002) advocated asking students to “accept the responsibility for learning. This involves developing the intellectual maturity, learning skills, and awareness necessary to function as independent, autonomous learners” (p. 95). A critical aspect of the course is the integration of multimodal composition. Students are required to think critically about the types of documents they produce based on a specified audience, and for some projects students compose in multiple modes. On the way to becoming such learners, students benefit from working with others in Vygotskian zones of proximal development: “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). Students are prompted to make choices about writing and provided tremendous amount of instructional support; additionally, students are also provided a rich learning environment.

Designing the Learning Environment

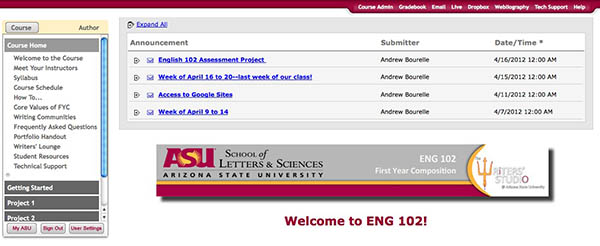

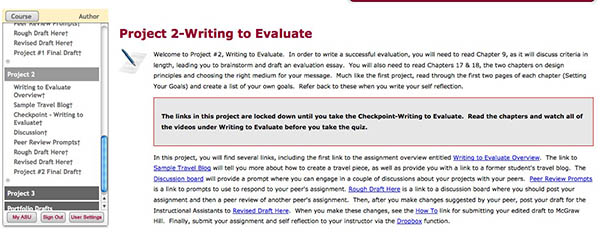

The learning environment itself takes careful planning. For instance, when designing the Writers’ Studio courses, faculty partner with the university’s online course designers on the platform layout for visual appeal and accessibility compliance (see Figures 1 and 2). In addition to using disciplinary theories to build the first-year composition courses, faculty also use the Quality Matters (2010) rubric to ensure successful online scaffolding. The rubric is based on “solid research literature, eleven national standards of best practice, and instructional design principles” to help course developers design an efficient and effective online classroom that “integrates learning objectives, assessments, and activities,” focusing on student needs in an online learning environment. The course was designed around the eight components of the Quality Matters rubric, which include the following: course overview and introduction, learning objectives, assessment and measurement instructional materials, learner interaction and engagement, course technology, learner support, and accessibility.

Figure 1. Course welcome page

Figure 2. Course unit overview page

COURSE OVERVIEW

Beyond traditional introductory materials, such as course syllabi, Writers’ Studio offers students a video overview of the course, including an explanation of how the course differs from a traditional first-year composition class. Students are given a video tour and hyperlinks to become familiar with the course shell. Instructors also produce self-introduction videos, providing students opportunities to “meet” their teachers and hear advice about how to succeed in the course. Throughout the course, students encounter videos from teachers and advanced students on rhetorical concepts. Video 1 is an example of an introductory video where students “meet” the instructor of record.

Video 1. Instructor introduction to course

Learning Outcomes

Following the Quality Matters (2010) rubric of objectives, assessments, and activities, teachers use the Writing Program Administrators Outcomes Statement (WPA OS) and the eight habits of mind from the “Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing” (WPA, NCTE, & NWP, 2011) as course outcomes. Approved in 2000, the WPA OS highlights national expectations of student learning by the end of first-year composition; this document has continued to evolve (see 2008 amendment), because it is an accumulation of “practice, research, and theory.” Three professional organizations—Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and National Writing Project (2011)—developed the “Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing” to enhance student preparation for postsecondary education. This document was developed by college and high school writing faculty across the nation, as a response to the Common Core State Standards. The Framework for Success contains a section entitled “Habits of Mind,” which refers “to ways of approaching learning that are both intellectual and practical and that will support students’ success in a variety of fields and disciplines” (WPA, NCTE, & NWP, 2011). These documents together serve as the foundation for the Writers’ Studio course learning outcomes.

Assessing and Measuring

The WPA OS and habits of mind are important in the assessment component of the Quality Matters (2010) rubric because the rubric “stresses the importance of all course learning activities and assessments being aligned with the course learning objectives.” To determine how effectively students respond to the course outcomes, students produce multiple drafts of each project, which cumulate in a capstone project: an eportfolio. In the eportfolio, students demonstrate understanding of course learning outcomes through reflective discussion using the projects, drafts, and other coursework as evidence of learning. Students in the Writers’ Studio assess their growth with each project through a metacognitive reflection, which accounts for student ability to demonstrate understanding of project goals based on the course goals. Building on project metacognitive reflections, students address in the eportfolio how thoroughly and effectively they have demonstrated the course outcomes.

Delivering Instructional Materials

The online courses also engage students through multiple learning approaches: multimodal instruction, faculty-produced videos, audio lectures, and other digital supplemental content. The following videos are example supplemental material; Video 2 is used as a prompt to ask students to discuss their definitions of rhetoric, and Video 3 offers an overview of the portfolio project.

Video 2. Prompting discussion of rhetoric

Video 3. Providing an overview of the portfolio project

Additionally, the course textbook is fully online and embedded within an interactive site, complete with supplemental videos and former students’ digital projects. From the textbook to the videos in the course, all materials in the Writers’ Studio exemplify multimodal texts. While a traditional classroom might privilege textual literacy, the redesigned curriculum promotes a variety of literacies needed for the 21st century (Brandt, 1995; Daley, 2003; Hawisher, Selfe, Moraski, & Pearson, 2004; Selfe, 2009).

LEARNER INTERACTION AND ENGAGEMENT

Students within a course are divided into small, 20-student cohorts, or writing communities. To promote interaction among peers, instructors ask students to post messages in multiple communicative venues according to their writing community groups; these include discussion boards, journal entries, and drafts of portfolio sections. To foster relationships among peers, in response to multimodal assignment prompts, instructors ask students to produce multiple drafts and participate in peer review for each project.

Because providing writers with rhetorically appropriate and timely feedback is crucial for developing their knowledge and skills, within the Writers’ Studio, students receive in-process feedback from multiple sources: peers in the class, instructional assistants (upper-division students), tutors in the writing centers, and instructors. The speed with which students move through these feedback cycles depends upon whether the courses are taught in 15- or 7.5-week courses. In a 15-week course, for example, students might spend up to a month on a particular project. They have a week to give and receive peer review, another week to obtain feedback from instructional assistants, and then another week to take advantage of tutors. Throughout this time, the students are ideally making revisions with each subsequent draft. During this time, they are also participating in discussion forums, reading assigned chapters of the textbook, and completing other tasks related to the projects. When courses are taught during the 7.5-week schedule, the timeframe is compressed.

To guide the feedback so it is consistent across all five types of responders and all media in a variety of genres, faculty developed rubrics for the course projects and the portfolio (see Appendix A). Because students may elect to use a variety of genres, the rubrics reflect rhetorical concepts that can be applied to projects across the spectrum. As Georgine Loacker, Lucy Cromwell, and Kathleen O’Brien (1986) noted, “learning increases, even in its serendipitous aspects, when learners have a sense of what they are setting out to learn, a statement of explicit standards they must meet, and a way of seeing what they have learned” (p. 47). In using rubrics teachers have experienced what Mary Huba and Jann Freed (2000) observed:

When we use a rubric as the basis of conversation with a student, we have an opportunity to engage in a mutual dialogue about learning. The student grows in understanding of the course goals and the standards of quality, and at the same time, the students can share information about how he or she learns best. Teachers and students can talk together, reflecting on students’ work and mutually assessing it using the rubric (p. 171).

In addition to using rubrics as a means for responding, some instructors use a variety of media to provide students with feedback, including video, audio, and written feedback.

Engaging Course Technologies

Establishing an interactive learner-centered environment, instructors produce videos to enhance student learning and to teach key concepts. Pamela Sherer and Timothy Shea (2011) noted that the millennial generation “has been connected to the new technology throughout their development and they expect that teaching and learning will be more interactive, collaborative, and experiential” (p. 57). Through the use of Web 2.0 tools, students encounter strategies for meta-learning, enhance knowledge-building skills, and contribute to a community of learning. Specifically, videos explain assignments and offer students advice on composing drafts, increasing the potential for students to become engaged with the material.

Students also receive feedback from instructors through audio, screen capture, and print. In the commentary, students receive direct feedback on the project learning outcomes. For instance, an instructor will typically use the project rubric to offer ways in which the student has been successful in meeting the project criteria, including historical content and narrative capabilities. If necessary, specific and direct feedback might relate to a lack of citations or to guidance on the rhetorical concepts of audience, situation, purpose, genre, and medium—all discussed within the project self-assessment, with an eye toward the student portfolio. Along with the commentary, students also receive a written summary and the rubric with marked sections indicating progress.

Providing Learner Support

To respond to student questions efficiently and effectively, each course discussion board, called a Writers’ Lounge, is designated for general questions. In this virtual space, students post questions about the course and any member of the instructional team or other students offer responses. Students are encouraged to post in the Writers’ Lounge, rather than emailing the teacher directly, so that all students can benefit from the answer. As with any course, students ask questions about assignment guidelines, technical aspects of a project, and key course concepts.

The university’s course platform, hosted by Pearson’s Learning Studio, offers 24-hour support to students experiencing technical difficulties. Arizona State University provides technical support for students enrolled in online courses, and the publisher of the textbook used in the Writers’ Studio, McGraw Hill, also offers support for students experiencing problems with accessing the textbook and the supplementary online materials. Furthermore, the design of the Writers’ Studio, as discussed above, gives students access to a multitude of support services, including peer mentors and various instructors within the courses. Lastly, students are provided videos and instructional materials on multiple technologies a student might be using to compose a text (e.g., audio recording and editing with Audacity, or creating their course eportfolio on Google Sites).

Ensuring Accessibility

Faculty curriculum developers build course content within the platform of Pearson’s Learning Studio because it is “capable of delivering online learning to students with disabilities” (Pearson eCollege, 2011). The university-employed instructional designers worked with the faculty redesign team to deliver courses in accordance with standards set forth by Section 508 of the American Rehabilitation Act. For instance, when a student scrolls over the each graphic or video, a description of that image is embedded, attending to students who may not be able to hear the video or who may have trouble viewing images on a screen. Additionally, curriculum developers wrote interpretations of digital resources for students who could not view the videos, which may include not only students with disabilities, but also those who may not have access to high-speed Internet. Developing an accessible course requires considering students who have disabilities, and also accounting for how materials are presented for learner success.

In the following sections, we highlight student development of learning outcomes as expressed through their eportfolios and discuss changes to the curriculum to further enhance learning.

STUDENT PORTFOLIOS

To offer writing assignments that respond to the WPA Outcomes Statement (WPA OS), Writers’ Studio faculty have expanded writing assignments beyond the limited offering of one genre (the academic essay) and one medium (print) to encourage many genres and media. The very act of making choices requires students to carefully examine rhetorical knowledge, a core concept of the WPA OS. Rhetorical knowledge is central for engaging students in the foundation of rhetoric. Lester Faigley (2003) asked teachers to

think about rhetoric in much broader terms. We have no justification aside from disciplinary baggage to restrict our conception of rhetoric to words alone. More important, this expansion is necessary if we are to make good on our claims of preparing students to engage in public discourse. (p. 187)

Writers’ Studio serves as a model for teachers to be open to all available means of representation and locate resources that aid students in multimodal composition. Student projects can and should include images, audio, and video to “expand the notion of control beyond the page that they could think in increasingly broad ways about texts” (Takayoshi & Selfe, 2007, p. 2). The multimodal projects work together as building blocks to assist students in the ability to demonstrate learning for the course electronic portfolio.

Portfolios have long been used as assessment and evaluation tools in first-year composition classes. One benefit of using portfolios is that they showcase student progress throughout the semester, helping the student and teacher to see the improvement that occurred over time. As Edward White (1994) observed, “the portfolio exemplifies the teacher’s definition that writing is a process, not merely a product. Although the portfolio contains a series of products, as a whole it is evidence of the student’s writing process” (p. 121). Moreover, students are more likely to see value in a comprehensive portfolio over simply writing one paper after another without—seemingly—any connection between them. White paralleled the use of portfolios to the ability to capture a motion picture of student learning, opposed to a snapshot, which is what a test might capture.

Although the benefits of portfolios are many—among them, that students are assessed based on their work throughout the course, not individual projects—scholars have worked to find appropriate means of portfolio evaluation. White (2005) pointed out that “holistic scoring is particularly unsuited for evaluation of portfolios” (p. 586). For Writers’ Studio courses, our instructional team adopted a variation of what White describes when he argued that “students should be involved with reflection about and assessment of their own work” (2005, p. 583). White proposes an alternative method that depends upon two activities: first, the faculty develop a set of goals for the course or program that is included in the course materials; second, students compose in-depth reflection letters articulating how they have met (or failed to meet) those goals, using the contents of the portfolio as evidence (p. 586). The reflection document acts as an argument from the student that the course goals have been met. The contents of the portfolio constitute evidence the students can draw from in making their claims. The act of writing the document and organizing the portfolio are, at once, reflective and rhetorical.

Although self-reflection letters are commonly used in conjunction with a portfolio’s contents, this format raises the importance of the reflection by aligning the project with the goals of the course. The reflective document becomes an important aspect of the assignment, as the student accounts for learning throughout the semester. The project self-assessments are used in developing the portfolio reflection. White (2005) explained that this form of evaluation “requires that the goals for the portfolio assessment be well understood from the start by the students submitting their work as well as by the readers doing the scoring” (p. 588). From the first day of class, students are told that the ultimate goal of the course is to build a portfolio that demonstrates learning throughout the semester. During the first few days of class, course materials clearly outline that each project is a key component to the portfolio, and students are required to assess learning on a micro and macro level. The self-reflection is not something to be completed quickly at the end of the semester. As White noted, “The reflective letter is a genre itself, and a difficult one to do well” (p. 594). The portfolio is a significant project that students develop all semester, as sizeable as any of their major writing assignments, if not larger in scope and importance.

In the following sections, we explain how we put this portfolio pedagogy into practice. Afterward, we share comments from students from their portfolio reflections, hoping to demonstrate not only the effectiveness of the eportfolio in accomplishing the course outcomes, but also to demonstrate that the design of the course—with its emphasis on multimodality and the use of instructional assistants to promote process—enhances student learning.

Prioritizing Portfolio Reflection

The portfolio method of reflection empowers students to demonstrate their learning. Portfolios, with the comprehensive and detailed reflection, give them greater agency in their education. This approach has advantages over basing grades on a composite of papers alone. The essays—and, in our case, multimodal projects—demonstrate some of the learning that occurs; however, writing projects alone cannot demonstrate the full range of learning that occurs.

In the course eportfolio, each student makes the following claim: “In light of the learning outcomes for this course, here is what I have learned.” To support that claim, the student offers concrete evidence in response to the WPA OS and habits of mind such as excerpts from course projects, online discussion, invention work, journal entries, and transcripts of online peer reviews. Further, the student engages in analysis and metacognition by reflecting on the pieces of evidence to explain how they specifically demonstrate particular learning. The portfolio includes appendices, which include full projects for the course. The portfolio, as Kathleen Yancey (1998) noted, is “reflection-in-presentation,” demonstrating “relationships between and among the multiple variables of writing and the writer in a specific context for a specific audience, and the associated texts” (p. 14). The act of constructing such course portfolios helps students move from tacit knowledge (knowledge that they cannot articulate) to explicit knowledge (knowledge that they can articulate; Polanyi, 1958).

From the first day of the term, students are provided with the goals for the course and explanation that for the majority of their course grade they will produce a portfolio with a comprehensive reflection addressing six distinct parts: one each for the five areas of the WPA OS and another for comprehensively addresses the eight habits of mind. Throughout the semester, students write reflections on each project they submit; these project reflections are two-fold in that students can immediately assess learning occurring throughout the semester and students can pull from the project reflections when composing the portfolio reflection.

When evaluating the final portfolios, teachers concentrate on the reflections with the evidence the students provide to show they have achieved the goals of the course. Because the individual writing projects must reach a “portfolio-ready” status, instructors do not necessarily need to reread every piece in the portfolio. This technique is consistent with White’s (2005) suggestion: this approach to evaluation, he said, “does not intend or need to regrade papers that have already been read and commented on” (p. 593). White pointed out that because “the reader is relieved of the necessity of giving new grades to each item in the portfolio, it is now possible to give a reliable and reasonably quick reading to the portfolio in hand” (p. 594). Because grading the portfolio emphasizes the reflection letter, not just the writing projects themselves, grading is more manageable, which keeps the teacher workload manageable per the provost’s call to maintain a reasonable faculty workload.

Situating the Portfolio Rubric

Writers’ Studio students are provided with a rubric for understanding how the portfolio will be evaluated, just as they are provided with individual rubrics for their papers throughout the semester. The portfolio rubric (see Appendix B) covers the following categories: Organization of Content, Clear Sense of Purpose, Clearly Stated Claims, Sufficient Evidence, Critical Reflection, and Conventions. It also addresses the WPA OS and eight habits of mind. As one can see from these sections, most of the items connect specifically to the reflection students write.

For “Organization of Content,” teachers consider how the student has arranged the portfolio content. Students develop their electronic portfolios using Google Sites, and it is important for the students to organize their web pages in such a way that the teachers can easily locate writing projects from the semester as well as reflections for each of the outcome areas. At the same time, organization applies to the reflections themselves and the way students have made their argument for achieving the course goals. Likewise, having a “Clear Sense of Purpose” applies not only to the portfolio as a whole but also the reflection. All content has a unifying purpose: the demonstration of student learning during the course of the semester. From the start of the class, students are told contents of the portfolio and its accompanying reflection are connected, not disparate elements thrown together on a web site.

The next few items on the portfolio rubric—“Clearly Stated Claims,” “Sufficient Evidence,” “Critical Reflection,” and “Addresses the WPA OS and Eight Habits of Mind”— relate directly to the reflections the students write. The rubric item “Conventions” covers student ability to produce reflections with appropriate punctuation, spelling, syntax, mechanics, citation, and use of genre capabilities. As with the other writing assignments for the course, the reflections must be thoroughly edited in addition to being carefully and thoughtfully written.

Using portfolios this way applies a goals-oriented approach for the class as well as an effective measurement tool. At the same time, the portfolio encourages students to view their work in broader terms than simply fulfilling course requirements. White (2005) stated that “when the reflective letter requires them to consider what they have learned and accomplished in terms of the program, rather than of individual courses, they gain a new sense of responsibility for the choices they have made” (p. 592). In the first semester of the Writers’ Studio, teachers saw this idea evidenced, as students gained not just a perspective on the importance of the course, but also came to better understand how what they learned can be used in the future.

Reviewing Student Portfolio Responses

Huba and Freed (2000) noted that one of the most important reasons to provide outcomes is to “reveal to students the intentions of the faculty” (p. 97). When students understand the goals of a particular course, they “are in a better position to profit from the experiences” (p. 97). Indeed, the Writers’ Studio’s pilot semester revealed that the students benefited not only from being given the course outcomes, but also from being asked to reflect on their learning based on the categories established by the course outcomes.

Rhetorical Knowledge

The first reflection category in the WPA OS is rhetorical knowledge. For the eportfolio, students were asked to demonstrate understanding for each of the six bulleted points listed within the area of rhetorical knowledge. For example, the last bullet point within the rhetorical knowledge section is that students are expected to “write in several genres” (CWPA, 2011). Several students indicated that they learned through writing a genre that they had never attempted before; many students expressed surprise about writing in multiple genres because they previously had to write one essay after another. One student stated, “I learned many different types of ways I can get my point/message to my audience.” This student developed a travel blog for an evaluative assignment, as well as a public service announcement web page that accompanied a “solving problems” argument. She stated, “I liked using pictures to draw my audience in and facts are important to use to convince and inform an audience,” adding, “genres should be appropriate for whatever the topic is. It should keep the audience interested and informed.”

These comments overlap with other points within the rhetorical knowledge outcome area—such as “respond to the needs of different audiences,” “use conventions of format and structure appropriate to the rhetorical situation,” and “understand how genres shape reading and writing”—and the students made connections to the overlap as well. In fact, the overlap occurred not only within an outcome area, but also among the outcome areas, as students identified how “Composing in Electronic Environments” was an intricate part of “Rhetorical Knowledge.”

Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing

In the “Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing” section of the WPA OS, students identified that they learned to understand a writing assignment as a “series of tasks” as well as how to “integrate their thoughts with those of others,” using both primary and secondary sources (Council of Writing Program Administrators, 2011). One student stated that “integrating my ideas with my sources is what took the most time. I wanted it to flow perfectly and really use my sources as a boost to my points, which I did.” She added that it took a while, but after she worked on integrating sources throughout the semester, she “finally got the hang of it.” Besides integrating the thoughts of others, students grew in other ways. The same student who integrated the views of others stated that “when I successfully completed my three projects, I finally realized why using reading and writing for inquiry, learning, thinking and communicating was so important.”

Writing Process

Because Writers’ Studio places heavy emphasis on process—with students receiving feedback from peers, instructional assistants, and the instructor as well as the writing center and/or publisher’s tutoring service—students see significant changes from their first drafts to their final portfolio drafts. One student stated that she benefitted from the multiple draft-and-review process: “I believe that good feedback from a peer, instructor, or even a friend who's willing to take the time to do it, is essential to good writing.” This student and others commented that in addition to receiving valuable feedback, they appreciated learning how to give feedback:

One aspect that I learned a lot on this semester is giving feedback. I always felt unsure about giving my opinion on a piece of work. After reading through many other papers, I learned that for one thing I am giving my opinion about a paper and not necessarily what is right and wrong.

This particular student also found that he gained insight into his writing by reading the work of others. “I also learned that by reviewing other works,” he stated, “I gained different perspectives and points of view that I would otherwise not have known, and sometimes these actually help me get through a writer’s block on my own papers.”

Knowledge of Conventions

The “Knowledge of Conventions” outcome area asks students, among other activities, to practice using the standard features of a genre, documenting sources, and controlling surface features such as syntax, punctuation, and spelling. Students commented in particular about integrating research into their projects by appropriately attributing sources. One student noted that “it has been a struggle to differentiate MLA from APA formats throughout the semester since I have classes utilizing both formats.” However, she added, “I have successfully gotten a better grasp on what I should and should not be doing in each format.”

Aside from documentation, students said that the extensive process work in the course helped them hone their editing skills and recognize the importance of polished, error-free prose. The same student who struggled with differentiating MLA and APA style stated, “grammar, punctuation, spelling and syntax are just as important as the content of an essay. If there are incorrectly spelled words or poor grammar, it takes away from the credibility of the writer.” This idea of credibility being linked to a mastery of conventions was a common theme in student reflections. For example, one student stated:

The interviewer reading my resume with several misspellings will likely toss my resume into the trash. My proposal at work to request personal time off may not be taken seriously if it is full of grammatical errors and incorrect punctuation. Controlling these features allows us to properly convey our message in the manner intended; the reader's opinion of me may be altered if I fail to use the best word choice and correct grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

Composing in Electronic Environments

Although genres certainly exist among print-based writing, having the class focus so heavily on writing using digital media helped students learn more about genres. Likewise, learning “to compose in electronic environments” was accomplished at the same time. “Messages are conveyed differently through electronic formats than they are in print,” stated one student, adding:

This class taught me that print and electronic processes can each be beneficial for a specific assignment. An APA-formatted term paper may present a study more effectively than a PowerPoint presentation. A short PSA video can have a greater impact than a scholarly journal regarding diminished health from smoking.

With these examples, this student demonstrates her understanding of the importance of genre, audience consideration, rhetorical situation, and effective use of digital media in an argument.

Digital composition, in particular, was an area that students said they are most likely to benefit from in the future. For example, one student stated that she intended to start a blog to stay connected with family members. Currently, the family sends “round-robin” pictures and letters from family member to family member via mail. She described the activity as a “dying tradition” and, based on what she learned in class about making a blog, hopes to develop a blog to change the tradition. She stated, “having a family blog site may be a way to involve the next generation of cousins and aunts in a similar tradition allowing for posts of pictures and updated family news that is more real time and without copious postage fees!”

Students who previously had written only academic essays for school assignments became interested in composing in electronic formats in their lives beyond academia. With the production of blogs, websites, sound portraits, and other multimodal projects, online discussion boards, and an innovative “virtual classroom,” it’s easy to see how this particular section of the outcomes is accomplished.

Reviewing Student Portfolios: Habits of Mind

As mentioned earlier, in addition to the WPA OS, the Writers’ Studio incorporates into first-year composition programmatic learning outcomes from the habits of mind (WPA, NCTE, & NWP, 2011): curiosity, openness, engagement, creativity, persistence, responsibility, flexibility, and metacognition. Students were expected to reflect on each of these eight items as well.

Regarding responsibility, one student stated that the online format helped her to become self-disciplined. “Online students differ from most classroom students; without anyone telling us what do [sic], we must learn to organize our hours, personal and professional arrangements, and prepare for distractions,” she stated, adding, “with so many resources provided, like the syllabus, all due dates, complete descriptions of assignment requirements, etc., there is little room for excuses.”

Several of the learning goals are achieved through the assignments. About curiosity, one student stated, “writing an essay is like exploring an unknown world, especially when I had the opportunity to investigate and learn new things.” This testimony indicates that students benefited from engaging assignments. In addition to the writing students did during the semester, they often expressed piqued curiosity because of the different media used in crafting their projects. The student above, for example, stated, “my curiosity kept my mind consistently exploring new ideas and investigating those new thoughts. I was also interested in sharing the things I learned with my audience, and it in turn, created motivation for my writing.”

The different ways students composed their projects also fueled another habit of mind: creativity. As one student stated, “having several formats and genres available to us to formulate our pieces for this course helped me to develop creative approaches to convey my message.” Another said that she assumed the class “would be like every other English class I have taken before.” Students suggested the digital format of the class and the variety of genres and mediums used for the assignments prompted them to be more creative. Another student even surprised herself:

I am the antithesis of creative; I dread anything that has to do with art. When I saw that I had to create a blog page for the second project I was at a total loss of ideas and what to do. In looking at other blog sites I realized that I was drawn to the ones that had great graphics and told the story of the location in pictures more than just words. I embraced the challenge and felt that I did a good job creating a fun looking blog site.

Remarks from the student portfolios in our pilot semester are helpful in seeing the effect this activity had on their learning. Several students commented that they recognized that thinking about their writing—throughout the semester and not just at the end—benefited them. One student stated in her portfolio:

Each project for this course afforded me an opportunity to reflect on how a particular aspect affects me as a writer. For each succeeding project, it was very helpful to formulate and express what we learned from the previous one. We aren't often asked [in other classes] what we learned about an assignment, nor are we typically able to express our opinion about a particular aspect of a project. This class taught me to analyze the requirements, goals, and outcome of a specific project in order to benefit from it.

Others commented that they had never completed reflections to the degree this course required.

Because reflection was an integral part of each project, students admitted to being more aware of what they were learning as they were learning it. One student stated,

Throughout the semester, we had to consistently evaluate our work, which included evaluating our thoughts, ideas, and the processes by which we followed as individuals to reach a goal or complete the essay. I had to evaluate how I was writing and generating ideas, or creating the flow to my essay throughout the semester. I had changed this process by Project 2, as I found some things worked better than others.

Comments from students about personal and intellectual growth during the semester indicate the importance placed on the portfolio reflection.

ASSESSING THE WRITERS’ STUDIO

Writers’ Studio courses were designed with the typical assessment cycle in mind (Diamond, 1998). We began with learning outcomes: what students should be able to do by the end of the course. We then decided on curricular materials and pedagogical approaches to achieve the learning goals. When we designed the course, we secured IRB approval to use student work for research and publication. We gathered evidence, particularly in the form of student course eportfolios, as well as anecdotal observations of how students engaged with course materials, with instructional staff, and with each other. We have analyzed the available evidence so that we, like our students, can thoughtfully reflect on practice as we “combine faculty-generated ideas about what students need to learn with students’ active management of their own learning” (Schön, 1991, p. 342). The instructional team participated in a portfolio assessment with a second round of reviewers and analyzed the findings. From the findings, changes were made to the course model and curricular materials.

Revisioning Based on Portfolios

There were some overall trends in the portfolios, as summarized in Table 1. First, in both English 101 and English 102, students struggled with providing sufficient evidence to support their claims that they had learned specific knowledge and skills in the course. Given our interactions with students, we think that students assumed that their instructors would already be familiar with the supporting evidence because the instructors had seen student work throughout the course. However, it is interesting that students in English 102, a course that explicitly focuses on forms of argument, did provide more supporting evidence than students in English 101, which does not explicitly focus on argument.

Students in English 102 also addressed the WPA learning outcomes and the habits of mind more thoroughly than English 101 students did (see Table 1). This phenomenon makes sense because students in English 102 are presumably building on what they learned in the previous course, English 101. We find it puzzling that students in English 101 scored higher than English 102 students in organization and purpose. One possible explanation could be that the assignments in English 102 required more complex organizational structures; therefore, the students were challenged more in this area. For example, the first assignment in English 101 is a “writing to share experiences” project in which the writing is often organized sequentially or chronologically. Conversely, the first project in English 102 is a “writing to convince” argument wherein students must successfully present an issue, provide convincing reasons, support those reasons with evidence, and offer an honest discussion of alternative points of view, all in a clearly organized package with smooth transitions and a consistent tone. It makes some sense that organization and clarity of purpose in such an assignment might be more difficult for students. Additionally, because students in ENG 101 are setting up their eportfolios, more direct instruction and feedback may be offered; students in ENG 102, however, are often building on work from ENG 101. The instructional team has observed that students who took ENG 101 at other institutions did not come to ENG 102 with knowledge of how to develop a portfolio; students who had taken ENG 101 at our institution, however, were familiar with both portfolio development and the WPA OS as learning outcomes.

Table 1 :Teacher Participant Profile

| Course | Portfolio features | ||||||

| Organization of content | Clear sense of purpose | Clearly stated claims with critical reflection | Sufficient evidence | Address WPA Outcomes and eight habits of mind | Conventions | Overall | |

| English 101 | 3.36 | 3.40 | 3.09 | 2.06 | 2.96 | 3.22 | 2.72 |

| English 102 | 2.98 | 2.98 | 2.95 | 2.56 | 3.23 | 3.20 | 2.88 |

When assessing the eportfolios, we found that students were challenged to demonstrate learning outcomes. For example, some students struggled to respond to the outcome of Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing. One student claimed, “critical thinking is one of the most mind boggling activities. I definitely strengthened my mind muscles with just these three components (writing, reading, and critical thinking).” Specifically, within this outcome area, students struggled to respond to the bullet point “understand the relationships among language, knowledge, and power.” While some did not reflect on this point, others attempted but failed to provide evidence to support their learning. Another student stated, “having knowledge of language is how someone can have power. An accumulation of knowledge if [sic] very important, and a goal that everyone should have.” While the student’s response hints at a relationship between knowledge and the ability to use language effectively, he fails to show his reader evidence that suggests he has learned this skill.

Student apprehension may indicate that this outcome area—Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing—needs more elaboration for student action and comprehension than other outcome areas. In the WPA OS, this category specifically addresses information literacy skills—the ability to locate and evaluate information to use as support in sharing ideas. The language provides flexibility because references to what students should be able to demonstrate are vague. The tasks that students should complete when using readings and researched materials are not clear. Although teachers traditionally place a heavy focus on understanding and interacting with outside texts, methods for assisting students in meeting this particular outcome area could be made more clear.

To further complicate the responsibility for students to learn methods for critical thinking and engagement with texts, faculty members sometimes make false assumptions about student prior experience, understanding, and capabilities on how to actively read and respond to texts; locate, evaluate, and synthesize research; and integrate outside texts as support for their texts. These skills are paramount to student success not only in writing courses, but also in courses across the curriculum. Teachers of composition can assist students in critical thinking by requiring reading and researching activities, such as dialectical journaling, synthesis, summarizing, questioning, locating, evaluating, and interpreting texts. As Linda Adler-Kassner and Heidi Estrem (2005) noted, students need a “wide variety of experiences that would stretch their literacy” (p. 60). Literacy activities occur not only in the production but also in the consumption of texts. Students can develop literacy by interacting with texts and analyzing texts to understand the rhetorical decisions other writers have made regarding rhetorical knowledge, process, and knowledge of conventions.

Because the WPA OS was developed for teachers by teachers, Writers’ Studio faculty strive to more clearly explain to students the learning outcome areas. Specifically, in response to the confusion about how language is related to knowledge and power within CTRW, we provided a video for students, walking them through a former student’s portfolio, explaining how they might respond to the outcome and provide evidence to support their learning. To facilitate learning, we developed a unit that encourages students to discuss and reflect on their learning. First, we produced a video to guide students through the student’s portfolio. We then prompted students to write reflections, using evidence to support their learning, and to discuss their reflections and provide peer review. With the new video, discussion board, and opportunities for reflection and peer review, we hope to see improvement in student learning of this important outcome.

Addressing the Challenges of Change

In our ongoing conversations with colleagues teaching within Writers’ Studio, we have come to appreciate the challenges of moving from a traditional ways of thinking about composition in which one instructor is autonomously responsible for all the instruction in a course section. In the Writers’ Studio, instructors work in teams, which means they need to agree on who will be responsible for which instructional tasks. Although these decisions require negotiation among the faculty, we have been impressed with how effectively and collegially faculty have worked with one another and with the instructional assistants and tutors. When challenges arise, Writers’ Studio faculty have collaborated to find solutions that serve the interests of colleagues, students, and the institution. In addition to working collectively, the team has faced the need to continue recruiting faculty members to teach and rotate in the various roles of the course to avoid burn-out as the program grows. It can be challenging to find instructors who are willing to change the teaching approaches that they have used throughout their careers—autonomously and face-to-face. However, because instructors have enjoyed teaching in Writers’ Studio, they effectively market the program to colleagues. They often talk about how teaching collaboratively in Writers’ Studio has re-energized their teaching.

The provost was concerned about maintaining or reducing faculty workload, and the newly developed program also was given the charge of reducing the budget. Reducing the cost of first-year composition is an ongoing effort. Although assigning some instructional tasks (i.e., tracking student participation) to personnel other than faculty is one method of realizing financial efficiencies, we are considering other possibilities. For example, by asking students to post their questions in the online discussion board, faculty do not have to spend unnecessary time responding to the same question multiple times, which offers time to address other responsibilities. In some cases, faculty don’t need to answer a question in the Writers’ Lounge even once, because students sometimes provide answers that are just as helpful as those that instructors could offer. An added benefit is that students often provide answers from the perspective of a peer learner, as someone who thoroughly understands what the question poser needs.

We have also considered whether digital tools, or software for editing, may save time. For example, could students benefit from computer-generated feedback on editing drafts of their writing? We understand the limits of such feedback, but we wonder if it could be used at some point in the process of student composing activities. First-year composition courses present special challenges for those who wish to reduce costs because, at this point in the history of education, humans are much more effective than computers in providing useful feedback to writers. Computers can evaluate certain surface features fairly well, but they are not very helpful for evaluating the writer’s thinking.

We are also challenged to maximize student success. After the initial launch of Writers’ Studio, we analyzed student success as measured by course grades. As we looked more carefully at the students who earned low grades or who withdrew from the course, we noticed that many of those students had entered the course with lower university admissions profiles. As a result, we now review the academic records (high school grade point average, transfer grades, placement scores, previous success in online courses) of all entry-level students before allowing them to register for Writers’ Studio. (We do not screen students in online degree programs because they are required to take online courses.) Students may appeal our decisions not to allow them to register for the Writers’ Studio, and we do consider mitigating circumstances. For example, some students with weaker academic records convince us that they have recently learned how to be academically successful, especially in online environments.

As a result of our experiences, we are also considering how we might develop a face-to-face version of Writers’ Studio on several of our institution’s campuses. An in-person version could serve the needs of students not yet ready for online learning or who prefer in-person instruction. We are contemplating how we can most effectively adopt or adapt current Writers’ Studio practices for a face-to-face environment. We are also talking with the writing center coordinators to determine how we can further collaborate with them to achieve greater synergy.

CONCLUSION

Although this model was designed to accommodate budget cuts, it provides an engaging learning experience for students, as they design multimodal projects using technology to enhance their critical thinking skills and expand their digital literacies. The Writers’ Studio instructional team has worked collaboratively and collectively, which allows teachers to scrutinize how to clarify and supplement learning outcomes. We hope that the lessons learned in designing and implementing this project can in some small way assist others facing the challenges of shrinking budgets; however, the intentional pedagogical design of this course could serve any program regardless of local budgets.

Regardless of budgetary issues, the Writers’ Studio offers learner-centered instruction that enhances digital literacy, emphasizes a heavy process-model of writing, and makes students agents in their learning. With a drive toward online education, teachers must be innovative and intentional in implementing learning outcomes for first-year composition. Alternative models are critical to re-envision ways to engage students in digital environments with digital tools. Our class design can serve as a model for other universities to follow in full or in part. However, we hope it can do more than that. We hope our project can serve to further conversations about online education and extend this conversation in new directions. We encourage readers to consider ways in which our pilot curricula can be adapted, complicated, and enhanced. As more and more classes are being taught online, we need to think about ways to not only provide sound online education but also opportunities to enhance the teaching of composition as a whole in the 21st century.

![]()

REFERENCES

Brandt, Deborah (1995). Accumulating literacy: Writing and learning to write in the twentieth century. College English, 57, 649–668.

Bruffee, Kenneth. (1984).Peer tutoring and the “conversation of mankind.” In Gary Olson (Ed.). Writing centers: Theory and administration (pp. 3–15). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Council of Writing Program Administrators. (2000). The WPA outcomes statement for first-year composition. Retrieved from http://wpacouncil.org/positions/outcomes.html

Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, & the National Writing Project. (2011). Framework for success in postsecondary writing. Retrieved from http://wpacouncil.org/files/framework-for-success-postsecondary-writing.pdf

Daley, Elizabeth. (2003, March/April). Expanding the concept of literacy. Educause, pp. 32–40. Retrieved from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/erm0322.pdf

Diamond, Robert. (1998). Designing and assessing courses and curricula: A practical guide (rev. ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Faigley, Lester. (2003). The challenge of the multimedia essay. In Lynn Bloom, Donald Daiker, &

Edward White (Eds.), Composition studies in the new millennium: Rereading the past, rewriting the future (pp. 174–187).Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Gillespie, Paula, & Lerner, Neal. (2003). The Allyn and Bacon guide to peer tutoring. New York: Pearson.

Harris, Muriel. (1988). Peer tutoring: How tutors learn. Teaching English in the Two-Year College, I, 28–33.

Hawisher, Gail E.; Selfe, Cynthia L.; Moraski, Brittney; & Pearson, Melissa (2004). Becoming literate in the information age: Cultural ecologies and the literacies of technology. College Composition and Communication, 55, 642–692.

Huba, Mary E., & Freed, Jann E. (2000). Learner-centered assessment on college campuses: Shifting the focus on teaching to learning. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Loacker, Georgine; Cromwell, Lucy; & O’Brien, Kathleen (1986). Assessment in higher education: To serve the learner. In Clifford Adelman (Ed.), Assessment in American higher education (pp. 47–62). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement.

National Council of Teachers of English. (2008). Position statement: 21st century curriculum and assessment framework. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/positions/statements/21stcentframework

Pearson eCollege. (2011). Accessibility: Pearson ecollege is committed to accessibility. Retrieved from http://www.ecollege.com/Accessibility.learn

Polanyi, Michael (1958). Personal knowledge. Towards a post critical philosophy. London: Routledge.

Quality Matters Program Rubric. (2010). Retrieved from http://www.qmprogram.org/rubric

Schön, Donald (1991). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Section 508 (2011). Section508.gov: Opening doors to IT. Retrieved from http://www.section508.gov/

Selfe, Cynthia. (2009). The movement of air, the breath of meaning: Aurality and multimodal composing. College Composition and Communication, 60, 616–663.

Sherer, Pamela, & Shea, Timothy. (2011). Using online video to support student learning and engagement. College Teaching, 59, 56–59.

Straub, Richard (1999). The concept of control in teacher response: Defining the varieties of “directive” and “facilitative” response. In A sourcebook for responding to student writing (pp. 129–152). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Takayoshi, Pamela, & Selfe, Cynthia. (2007). Thinking about multimodality. In Cynthia Selfe (Ed.), Multimodal composition: Resources for teachers (pp. 1–12). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Vygotsky, Lev S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Weimer, Maryellen (2002). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

White, Edward M. (1994). Teaching and assessing writing: Recent advances in understanding, evaluating, and improving student performance. Portland, ME: Calendar Islands Publishers.

White, Edward M. (2005). The scoring of portfolios: Phase 2. College Composition and Communication, 56, 581–600.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (1998). Reflection in the writing classroom. Logan: Utah State University Press.

![]()

Return to Top

![]()