Chapter 11

The Evolution of Digital Writing Assessment in Action: Integrated Programmatic Assessment

Beth Brunk-Chavez and Judith Fourzan-Rice

![]()

ABSTRACT

We offer the University of Texas at El Paso’s digital assessment for first-year composition as an example of how standardized assessment within writing courses can be tailored to accommodate the needs of specific courses and writing programs. We outline changes made to the traditional research and writing course as we brought it into the 21st century by incorporating technology in the assignments, in the assessment, in the textbook, and in our instructor preparation and professional development. The goal of this redesign was to provide students with both rhetorical and technological strategies and skill sets that would transfer to other courses and beyond the university and provide a wider variety of feedback on student writing than previously existed. In this chapter, we address the needs of students, the changes to assignments, and the implementation of a digital distribution system known as MinerWriter. Through MinerWriter, the program has improved and increased student feedback, improved professional development, improved the quality of programmatic assessment and feedback, and enabled students to write for a discourse community beyond their instructor. The chapter features several videos of how the scoring committee interacts with MinerWriter.

![]()

As writing technologies evolve, they change our understanding of rhetoric and writing studies; new technologies require new definitions of what we consider writing. First-Year Composition programs need to help students pay close attention to these new technologies and to compose effectively with them. To prepare students for the 21st century, in which writing means more than word processing essays and composing argumentative research papers, the First-Year Composition program at the University of Texas at El Paso (FYC@UTEP) engaged in a major redesign of its curriculum, course delivery, evaluation of student work, and program assessment.1 We created a two-course sequence in which students are immersed in a digital writing environment. In addition to several traditional writing projects, the curriculum was revised to include multimedia projects such as a video documentary and an online opinion piece, both of which are published online via advocacy web sites developed by students. Each second-semester class is delivered as a hybrid, or blended, course for which students do much of their analysis, research, composing, and publishing online via course-management systems, wikis, blogs, and web sites. Courses are held in computer classrooms, and our program textbook is published and sold as an ebook.

The redesign of the curriculum and new delivery approaches required that the program reconsider traditional grading and assessment practices because, in large part, “the changes wrought in writing with technology would produce different writing, and that different writing would call for different assessment methods” (Herrington, Hodgson, & Moran, 2010, p. 204). Inspired by Texas Tech’s ICON and TOPIC,2 we developed a digital assessment system to best suit our institutional context. As a result, we developed an evaluation and assessment system that continually provides feedback to the program on the quality of assignments, professional development, instruction, and, of course, student work.

After a discussion of the digital assessment system, this chapter addresses four affordances experienced while transitioning to this new mode of evaluation and assessment. We focus on both the ongoing development processes and the results, including the assignments and rubrics, professional development, multiple forms of feedback on student writing, and continuous programmatic feedback and improvement.

CONCERNS ABOUT STUDENT WRITING EVALUATION AND WRITING PROGRAM ASSESSMENT

FYC@UTEP’s previous writing evaluation and assessment model was very much in the “traditional” mode, where instructors independently interpreted course objectives and evaluated their own student work. At the end of each spring semester, we collected a portfolio of writing from randomly selected students. These portfolios were evaluated according to a program rubric that ultimately assessed the culminating research-based argument paper. The program assessment goal was to determine whether students were “competent” researchers and writers when they completed the final course project. Although this common assessment model served a variety of purposes, it had its limits, one of which was it singularly focused on the question of competency and therefore cannot consider and address additional programmatic issues such as grade inflation.3 However, of primary concern is the disconnect between assessment and instruction that can occur for a variety of reasons, including poor alignment between the program’s philosophy and the assessment tools, individual instructional practices that contradict the assessment measures, or the time it takes to revise a program based on assessment results. Because instructors are not generally consulted during writing assessment design (although they may participate in the actual assessment), writing attributes assessed do not always match classroom objectives. Nor do the results necessarily impact instruction the following semester.

These disconnects are not uncommon; in fact, they are the norm for many programmatic assessment practices. As Michael Neal (2011) reiterated, “writing assessment is often understood as separate and detached from teaching and learning” (p. 131). Additionally, this disconnect between program and instructor standards becomes especially visible, for example, when an assessed final project is rated incompetent according to program standards, yet the student received an A in the course according to an individual instructor’s standards. As a composition program responsible for the quality of instruction students receive, we sought a new program model that provided some measure of standardization to ensure consistency both in instruction and the evaluation of student work as well as one that allowed instructors to contribute to and benefit from ongoing assessment. Our answer was a digital assessment system created, maintained, and monitored by our instructors. To productively integrate evaluation and assessment results with instruction, every component of the redesigned course—learning outcomes, assignments, professional development, rubrics, and the evaluation and assessment process itself—had to be parts of a cohesive whole. The digital classroom coupled with digital evaluation and assessment gave us the opportunity to bring these components together to work toward improved writing instruction on our campus.

However, this new assessment model was not met without concern. As Ed White (1996) stated, “teachers’ concern for assessment that reflects their teaching has often hidden an unwillingness to risk any assessment at all” (p. 9). Faculty may be trepidatious about a process that so tightly links evaluation to assessment. However, instructors teaching first-year composition courses, including ours, are primarily adjunct faculty and graduate students. As a group, these instructors understandably have little investment in programmatic assessment: Their time with the program has been and will be short, their areas of interest may lie elsewhere, and they have limited knowledge of assessment research and scholarship. To them, the integration of assessment and evaluation, as White suggested, may pose the threat of exposing possible deficiencies in their teaching—weaknesses they may or may not be aware of.

White (1996) and Bob Broad (2003) helped us understand that assessment reflects what we value. Although the program certainly values effective writing instruction, we agreed that the evaluation and assessment process should measure student ability to utilize rhetoric effectively in a variety of rhetorical situations, rather than monitor an individual instructor’s ability to teach the curriculum. Therefore, this assessment is used not to single out instructors (positively or negatively), but to create a more responsive and responsible program that continually invites instructors to participate in course revisions as well as assessment creation and process.

MAJOR CHANGES IN WRITING EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Because the program redesign grant we received4provided funds both for professional development and for access to a software programmer, we had the opportunity to make significant changes to a composition program that had not been revised in decades. Working with colleagues in the program, we chose to implement an assessment and evaluation system that turned traditional writing instruction on its head by having students submit their projects to an evaluator other than their instructor. Following Texas Tech University’s lead, we created an electronic distributed evaluation/assessment (EDE/A) system, named MinerWriter (see Figure 1), in which highly prepared graduate student teaching assistants evaluate composition students’ projects. Through this process, 70% of student final grades in the second-semester course is determined via EDE/A.5Additionally, the Scoring Committee provides comments for revision on drafts of two major projects.

This evaluation and assessment system is digital because all work is conducted online: students upload their projects to the web site, the rubrics are provided electronically, and the graders upload their comments and completed rubrics to MinerWriter so that students and instructors can then retrieve them.

Figure 1. Login screen for MinerWriter

The evaluation and assessment system is “distributed” because student projects are disseminated or dispersed to members of the Scoring Committee so that the individual instructor is not the sole person who evaluates student projects.

Norming of the Scoring Committee

One of the several goals of electronic distributed evaluation/assessment is to prepare new graduate teaching assistants for effective writing instruction. To that end, the Scoring Committee consists of graduate students working toward their initial 18 hours of graduate credit in English, and are typically in their first year of a teaching assistant appointment. 6 The First-Year Composition Assessment Team, consisting of the Director, Associate Director, Assistant Director (a PhD student), and two experienced lecturers, prepares the Scoring Committee to evaluate student work, both textual and digital, effectively, efficiently, and consistently. Through the training materials and meetings, the team reiterates that:

Our purposes are many but to the students and faculty, our primary purpose is to provide an evaluative feedback system that supports the holistic feedback given in the classroom and the tutoring center. Our job is to apply the FYC criteria, based on the WPA outcomes (Council of Writing Program Administrators, 2008), to the student projects consistently and accurately.

To this aim, the first step in training is that the Assessment Team creates training materials. To do this, identifying information is removed from previously submitted projects which are then rescored by each member of the Assessment Team. To norm themselves to each other, the Team then meets to compare results and discuss rationales for the scores. Once the team agrees on a score for each sample project, a rationale is written and added to the training materials. Table 1 shows an example of a set score for a Literature Review and Primary Research Report Training Sample. It addresses each component of the rubric and is used during training to help Scorers understand how scores should be applied:

Table 1 :Training Sample

| Category | A | B | C | D | F | Comments |

Research questions (40 points) |

C | The questions permit the students to enter the topic. #3 question are two questions in one, and the subject is too far apart. Some bias is discernible, an honest attempt is made to be unbiased, so no deducting for that. #4 Question is biased. | ||||

| Relevance of info (30 points) | B | Interjects opinion and does not present the other side thoroughly. Because the questions were weak to be able to develop the answers, but they are relevant. Got deducted under questions. Writes “there is no shame” (opinion) on top of p.6. P.7 the last sentence of the paragraph. It’s a B because this doesn’t devalue the whole paper. | ||||

| Presentation of research (30 points) |

C | Only one side is shown in the use of research except in one place. None of the sources are introduced. | ||||

Primary research |

D | Good sources but no introduction, no explanation, no purpose, no methodology. | ||||

| Required and good quality and variety of sources (15 points) |

A | Required number of sources and good quality. | ||||

| Graphic images (10 points) |

B | The image is well sized, somewhat effectively explained, it is related to the research question, but the connection is not well done. | ||||

| Writing fluency (25 points) |

C | Many minor grammar and mechanical errors. Misplaced homonyms. Subject/verb agreement issues. | ||||

| Use of APA style (15 points) |

C | Electronic information left out of some sources, not double spaced, the two interviews should not be on the reference list, the interview questions should be in an appendix following the references, and references not alphabetized. |

The second step of scoring preparation begins the Monday after projects are submitted to MinerWriter. The Scoring Committee meets with the graduate student Scoring Team in a computer classroom to view all digital materials necessary for both commenting on first drafts and scoring final projects within a collaborative environment.7To remind scorers of the rhetorical strategies and skills that students should be learning in and transferring from FYC, these sessions begin by reviewing the course learning outcomes followed by the particular assignment outcomes. For drafts, the group also discusses effective marginal and summative commenting strategies based on the assignment guidelines and the rubric’s expectations. For the final projects, focus is placed on recognizing the various ways that students meet the goals of the assignment.

Because the Scoring Committee consists of Master’s students from creative writing, literature, English education, and rhetoric and writings studies, as well as rhetoric and writing doctoral students whose ideas about writing are informed by their various disciplines, the Assessment Team must prepare them to evaluate student writing according to the FYC mission statement and goals. Therefore, for each assignment, we discuss what rhetorical strategies and skills the composition students should demonstrate, how to identify and evaluate them, and how to encourage students to improve their projects. For example, composition students occasionally have a hard time recognizing and articulating how form affects message in the Genre Analysis assignment; this is an area emphasized during the commenting session. For the Literature Review and Primary Research Report, because the research questions focus and drive the projects, they are critical to student success and therefore require focused attention during norming. Once this discussion clarifies objectives, the training samples and rationales created by the Assessment Team are reviewed. Each scorer uses the rubric to score a sample, either individually or in small groups, before returning to the whole group discussion of the scores. As the discussion is opened to the group, a negotiation space is created. No matter how clear the Assessment Team feels the rubric is or how obvious an objective is, the Scoring Committee constantly refines it with questions and concerns.

Once the Scoring Committee has discussed sample assignments that reflect different levels of achievement, the scorers move on to “live” assignments that they download from their queue in MinerWriter. To ensure that Scorers are connecting assignment goals to student writing, after the Scoring Committee member has either commented on the in-process draft or evaluated the final project, it is sent to an assigned Assessment Leader. This leader then responds to the quality of the evaluation and either advises the scorer to continue commenting and scoring or provides guidance and requests additional examples of their responses to students. Once Scoring Committee members are advised to continue, they evaluate and score all projects in their queue. Whenever a scorer has a concern, the Assessment Leader, the Assessment Advisor, and the Director of FYC are available for consultations via email, text messages, or Blackboard (UTEP’s course-management system). In addition to the face-to-face norming sessions, the Scoring Committee also has the opportunity to communicate and norm online through discussion postings on Blackboard. In these spaces, they are able to discuss issues, ask questions, and express concern over a particular student project. In this way, they can collect feedback from virtually any member of the Scoring Committee. For example, after she had begun scoring, one scorer reviewed a documentary filmed mostly in Spanish. She posted a question regarding the acceptability of the documentary, particularly because she did not understand Spanish. During the online discussion, that documentary was compared to another also filmed in Spanish, but which included English subtitles. Through a lively discussion, the members of the Scoring Committee resolved the issue by focusing their attention toward audience and thereby helped the scorer evaluate the project consistent with program criteria. The final step of the scoring process is double scoring, which enables the composition program to assess the assessment. To achieve this, a Blackboard discussion area is used to redistribute projects to the scorers. Once both sets of projects are scored, the Assessment Team compares them and sends any discrepant scores to a third scorer for adjudication. Should all three scores be discrepant, a member of the Assessment Team adjudicates. Although this last phase of the process is time consuming, it enables us to evaluate the quality of the norming and determine whether or not the scoring is consistent.

In summary, the process for commenting on a submitted draft in MinerWriter is as follows:

- Instructors teach the assignments available via the program-produced online ebook, The Guide to First-Year Composition.

- Students upload project drafts to MinerWriter and receive email notification that the draft is received. Drafts are due on Fridays at 11:30PM, with a late-submission window open until Sunday at the same time. Because students sometimes present legitimate reasons for missing the submission deadline, MinerWriter administrators are able to upload their projects after the deadline. To help keep students on schedule, they are invited to receive deadline reminders via Twitter.

- MinerWriter distributes the drafts randomly into Scoring Committee member queues.

- Training on commenting commences Monday with training samples and discussion of commenting practices and purposes. It continues on Wednesday with another meeting, after which scorers are either cleared to evaluate all projects in their queue or are provided additional one-on-one training.

- Commented drafts are uploaded so that both students and instructors are able to retrieve them. Each draft includes a short reflection assignment intended to help students understand the comments on their draft and think about a revision plan.

The process for scoring a submitted final project through MinerWriter works the same way, except that scored rubrics with comments are returned to the students rather than the projects. Also, in the fall semester, projects are double scored for accuracy and training purposes. Therefore, the process continues:

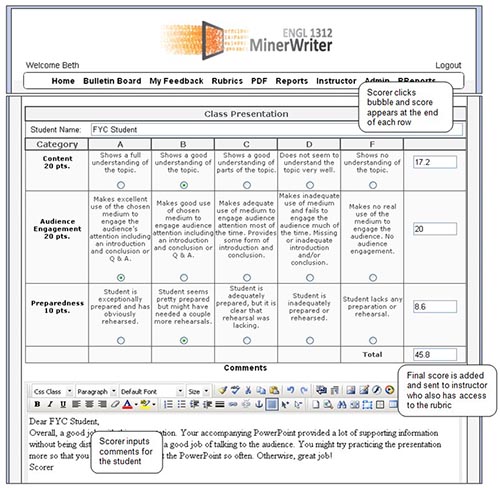

- Scorers download the projects from MinerWriter and make them available for double scoring through Blackboard (see Figure 2).

- Training for grading with the digital rubrics begins with sample assignments and discussion of acceptable scores for those samples.

- As a check, the Assessment Team redistributes downloaded projects in Blackboard for scorers.

- Scorers treat the second set of projects in the same way except they return scored rubrics to Blackboard.

Figure 2. MinerWriter rubric and comment screen

- The Assessment Team compares the double scores to determine if any need to be adjudicated.

- After all scores are checked and revised as needed, scorers are instructed to release their rubrics to students through MinerWriter.

- Students and instructors are able to retrieve the final projects, rubrics and comments.

Included here are three videos that demonstrate the process a scorer uses to evaluate a student project on MinerWriter. Two of them illustrate the scoring of a film documentary project; the third demonstrates the scoring of an online opinion piece.

Figure 3. Marcos scores a documentary film project. transcript

Figure 4. Sara scores a documentary film project. transcript

Figure 5. Marcos scores an online opinion piece transcript

The digital assessment system enables the composition program to provide a uniform assessment of writing abilities. It allows the program to receive projects, distribute them randomly to scorers, monitor commenting and scoring progress and quality, and return them to students and instructors in a secure and timely manner.

THE AFFORDANCES MINERWRITER HAS PROVIDED

William Gaver (1991) defined the “notion of affordances as a way of focusing on the strengths and weaknesses of technologies with respect to the possibilities they offer people who might use them” (p. 79). More specifically, Norbert Pachler, Ben Bachmair, and John Cook (2010) stated: “every medium, every technology that we use to represent and to communicate—to make and disseminate meaning—has affordances, both of material and social possibilities and constraints, that is, what is materially and socially possible to do with it” (p. 187). As WPAs and scholars, we should ask: What does the technology afford, or enable, and what does it prevent? How do we make meaning through its use and how does this new technology shape our understanding of teaching and evaluating writing? To consider these questions, we now turn to examine the affordances that MinerWriter with its digital rubrics has provided. Importantly, we will see how electronic distributed evaluation/assessment has afforded the opportunity to bring together what William Smith (2009) called two “very different purposes for direct assessment: ‘assessment of writer groups’ and ‘assessment of individual writers/students’” (p. 179).

Assignments and Rubrics

On a theoretical level, MinerWriter and the digital rubrics afforded the opportunity and incredible challenge of (re)defining local transfer objectives, program goals, and values. On a practical level, MinerWriter and the digital rubrics afforded the opportunity to perform timely, efficient, and consistent feedback and evaluation while widening student discourse communities beyond their instructors and classmates.

The new curriculum was designed to culminate in an advocacy web site, where all projects would be featured by semester’s end. Similar to an eportfolio, the collection of projects within the advocacy web site allows instructors to teach visual, aural, and textual rhetoric throughout the semester and provides students with a constant example of how and why different genres and discourse communities require different rhetorical strategies.

Creating this set of assignments—which included several digital projects and a set of rubrics by which to evaluate both the traditional and digital projects—became a highly complex process. Creating rubrics for the first two assignments, the Genre Analysis and the Literature Review and Primary Research Report, was challenging but familiar, given that they were traditional assignments new to the course, but not drastically different than what had previously been taught. Although students have the opportunity to rhetorically analyze digital genres and employ various technologies to complete the assignment (for analysis, research, and primary research presentation), the nature of the projects remained text-based.

The technologically innovative projects—such as the documentary, online opinion piece, and web site—presented challenging questions such as: How do elements like organization, thesis, and fluency transfer to these new genres and across media? Are there some “writing” elements that don’t transfer and others that need to be considered? How do we keep focus on the rhetorical elements required for a successful project? How do we make sure that the digital projects we assign remain appropriate to the context of a first-year composition course? And, how is evaluating an advocacy-based documentary different from evaluating an argumentative paper? As text-minded instructors, not experienced digital teachers, we found designing the assignments and their rubrics to be a challenging and intensively collaborative effort. For the digital projects, the redesign instructors began by addressing issues of color use, font size, functionality, and the overall layout and design of the web site. From there they gradually addressed the more-complex rhetorical tasks students would engage in (fair use of materials, evidence of editing, approaches to timing, and so on) as the program moved toward assigning digital compositions such as the film documentary.

The challenges in designing rubrics and evaluating digital projects, we found, were related to understanding the goals and learning objectives of the assignments and imagining how students would demonstrate their achievement of these objectives in their projects. Maja Wilson (2006) contended that rubrics become “writing assessment’s sacred cow” (p. 10) and suggested that rubrics dictate what is and is not acceptable. While there is truth in this, the rubrics were not the issue in the evaluation of student projects; after all, the assignments and rubrics were created simultaneously. Instead, it was the lack of understanding of what these new assignments and technology required of students that posed a challenge. Because these multimodal projects had not been taught before, we were unsure of what students would or could produce. This left us unsure of how to design a rubric for their work. Luckily, the rubrics were sufficiently general enough for faculty and students to grow into them. And while we knew what we hoped to offer students in the way of transfer, we were new to the how of it. Heidi Andrade (2000) envisioned rubrics as instructional, saying that,

at their very best, rubrics are also teaching tools that support student learning and the development of sophisticated thinking skills. When used correctly, they serve the purposes of learning as well as of evaluation and accountability. Like portfolios, exhibitions, and other authentic approaches to assessment, rubrics blur the distinction between instruction and assessment. (p. 1)

The projects that students complete today in UTEP’s composition classes are far more technologically and rhetorically sophisticated than they were 4 years ago, in part because the rubrics have served as instructional guides—malleable but constant. So, although Joan Garfield (1994) admonished, “remember that assessment drives instruction,” because our program was redesigning both curriculum and assessment simultaneously, we were able to treat evaluation/assessment and instruction as two sides of the same coin. The rubrics afforded the opportunity and challenge to define and evaluate student work according to what the program deemed as competent writing, as well as inform instruction and professional development.

Professional Development

As Roberta Camp (2009) articulated, the future of writing assessment should bring with it “increased attention. . . [to] the opportunities [it] provides for teachers’ professional development, for curriculum development, and for examination of institutional goals for learning” (pp. 125–126). The use of digitally distributed evaluation and assessment technologies afforded us the opportunity and the challenge of providing more professional development than the program had offered previously. Given the nature of our instructor pool, this is especially important. Composition courses at mid-size to large comprehensive universities are generally taught by a variety of faculty: part-time instructors, full-time lecturers, graduate students, and occasionally tenured and tenure-track faculty. Often these faculty members are overworked, temporary, have diverse scholarly interests, or represent some combination of these. Therefore, their philosophies and approaches to teaching writing are varied—sometimes widely so. This creates the very real and never-ending consequence where programmatic objectives and learning outcomes do not consistently reach students enrolled in the courses. So, although the use of distributed evaluation and assessment helped to create and establish clear program standards and apply them to assignments and rubrics, we realized that we could not create these new assignments and evaluate student work according to a program standard without thoroughly preparing the instructors to guide students as they produce the new textual and digital work.

Cynthia Selfe (2004) argued that “composition teachers have got to be willing to expand their own understanding of composing beyond the conventional bounds of the alphabetic. And we have to do so quickly or risk having composition studies become increasingly irrelevant” (p. 54). She went on to say, however, that courses incorporating new media and technologies in meaningful ways “are frequently taught by new media experts on whom the rest of the composition faculty—unsure about their own expertise or responsibilities to new media—confer the departmental responsibilities of dealing with emerging literacies” (p. 56). Selfe echoes our sentiments; we were visionaries, not multimedia experts—not yet. For this reason, we realized the importance of providing professional development workshops that offered instructors theoretical justification for teaching with multimedia as well as best practices for helping students attain course learning objectives.

Therefore, the digital assessment structure combined with the digitally infused curriculum provided the exigency for more scholarly informed professional development. The lines of inquiry we sought to address were: How do we help all instructors understand the roles of multimedia projects in a composition course? How can instructors prepare students to create projects with technologies they may not be comfortable with themselves? How can we prepare future instructors to recognize learning outcomes, address assignment goals, and provide effective and efficient feedback? We attempted to answer these by providing professional development workshops for all members of the program and intensive assessment training for graduate students on the Scoring Committee.

To that end, FYC developed mandatory back-to-school and monthly workshops that focused on topics such as visual rhetoric as well as optional workshops that allowed for an exchange of ideas related to completing individual assignments.8Topics for these optional workshops addressed “simple issues” such as uploading documentaries for grading and more advanced issues such as storyboarding and editing. Over time, we also invited guest directors from the various technology labs and centers on campus as well as faculty from upper-division courses where students work on multi-media projects. These guests helped faculty understand the relationship of today’s students to technology and writing, the assistance available to students and faculty on campus, and the importance and types of digital projects students will be expected to complete as they move beyond composition courses.

Although professional development workshops can prepare instructors to teach digital literacies and projects, there’s no doubt that learning to teach a new curriculum requires a significant investment of time and effort. Fortunately, another affordance of the digital distributed evaluation and assessment system we developed is that it reduced instructor workloads because other people were tasked with grading student work. The time-consuming task of grading can impact opportunities for professional development and individual student consultation. However, when instructors are not burdened with this time-consuming task for every project, their time can be spent updating their digital literacies, reimagining their pedagogical strategies, and providing more robust and individualized instruction. For example, one instructor who had previously used very little technology in her course developed effective methods for employing basic cell phone technologies to help groups communicate in and out of class. Another used podcasts as a supplement to the textual assignments and built his own web site that all his classes used. The combination of the workshops, additional available time for instructors, and student materials affords the opportunity to have all writing instructors confident about their multimedia expertise and responsibilities.

With distributed evaluation and assessment, preparing instructors is only half of the equation. There is also the responsibility of preparing scorers to be confident in their ability to evaluate student textual and digital projects. As any WPA knows, preparing novice instructors to evaluate student work is particularly challenging. An EDE/A like Miner Writer provides the Scoring Committee with the opportunity to work with real student writing under a guided structure for up to an entire academic year. In addition to the graduate course in composition theory and pedagogy in which graduate students also create a documentary, new teaching assistants tutor in the University Writing Center, observe students and instructors in courses, and work with instructors on mini-lessons. These activities inform their evaluation of student projects and help them develop teaching strategies for the next phase of their assistantships.

When the two most recent cohorts of the Scoring Committee were surveyed after their first semester, they had mixed responses regarding their experiences scoring the video documentary. Several said it was more challenging to evaluate a documentary because they were more accustomed to reading texts. Others said evaluating the documentaries seemed easier because they were more interactive and interesting. However, several members of the Scoring Committee made particularly insightful comments such as:

I think it was more difficult to grade the multimodal assignments, such as the documentary. The reasons behind this probably stem from the fact that I have more experience evaluating text-based assignments. I also tend to overvalue creativity and demonstrated technological skill. When these areas are strong, it can prevent me from seeing other areas that are not as strong.

Several scorers also commented that the documentaries were more difficult to grade because they were never “cookie cutter.” Although the literature review is a closed-form genre with a standardized structure and therefore a less interpretive rubric, the documentary is more of an open-form genre with a rubric that necessarily provides for flexibility in the ways students can achieve the assignment goals and objectives. Therefore, the range of documentary submissions—combined with the more open rubric—provided challenges that led some scorers to feel less confident about their evaluation of this project. This feedback is used by the Assessment Team to better prepare the cohort for the following semester.

When graduate student instructors who had transitioned to teaching were surveyed about whether and how their experiences on the Scoring Committee prepared them to teach, they claimed that the experience helped them understand a number of ways in which students struggle with their writing. One noted, specifically, that the experience “let me know in a real sense where a lot of these students are, what they are being taught, and what is expected of me.” Another commented: “I think it helped me figure out in terms of pedagogy and methodology what is effective for students at different levels of writing in the same classroom.” This knowledge is present as early as the first day they become an instructor rather than being developed as the semester moves along. Some of these scorers-turned-instructors have commented that being on the Scoring Committee prepared them to teach the second-semester class, but not the first-semester course where EDE/A is not used to evaluate student projects. However, because the next phase of assistantship begins in fall, and the first semester class is largest in fall, this issue is one we continue to work with; still, this feedback is used to help the program better prepare the next cohort as they begin to teach.

In addition to preparing the Scoring Committee members to grade and then teach for FYC, the digital assessment system also prepares these graduate students for future academic positions whether they move onto PhD programs in their discipline or teaching positions at a community college. Rather than independently learning to grade, they enter into an important dialogue very early in their teaching careers. This experience helps them to articulate their course objectives and goals, as well as what they expect from a writing assignment and why. It also prepares them for sophisticated conversations about grading, evaluation, and assessment, an additional asset on the job market.

Composition Student Feedback

Mary Jo Reiff (2002) stated that “professional communication scholars have long complained that writing in the academy assumes a monolithic audience instead of envisioning multiple readers with different needs and uses for information” (p. 100). In a traditional classroom situation, students generally receive feedback from one source: the instructor. Although they may seek feedback from a tutor at a writing center or receive feedback from classmates during peer review sessions, this scenario encourages students to see their instructors’ suggestions as inherently correct—after all, it is the instructor who will assign the grade. It is the instructor, therefore, who is right about their writing. However, to move beyond the scenario where students are instructed to “imagine an audience other than their instructor,” or fictionalize an audience, as Walter Ong (1975) suggested, the program thought carefully about how technology could afford students a wider range of feedback on their projects. Questions the program considered in regard to student feedback included: In addition to quality feedback, how can we leverage technology to provide a wider range of feedback to students? How can we assure that students receive sufficient and useful holistic and evaluative feedback on their projects?

An electronic distributed evaluation/assessment tool like Miner Writer has afforded the opportunity to provide composition students with a wider range and multiple layers of feedback reflective of the program’s standards. Research suggests that assessment is best when it includes both holistic and evaluative assessment. As early as 1985, the National Assessment of Education Progress recognized that holistic and “primary trait” scoring together provide the most reliability in assessment (Elliot, 2008). The EDE/A program provides consistent evaluation of student progress, which then frees instructors to provide more one-on-one, holistic feedback—what Wilson (2006) called “unmediated”—feedback both face-to-face and online. Coupled with the support students receive from the writing center and peer reviews, students can benefit from a number of types of feedback; in addition to the undergraduate tutors, members of the Scoring Committee as well as course instructors tutor at the University Writing Center. As much as possible, this ensures that feedback is consistent with scores and that students have ample opportunity to discuss, clarify, and improve their projects. So, although the Scoring Committee is charged with providing evaluative comments and scores of finished projects, instructors freed from the task of grading four of the major assignments can focus on the holistic scoring of process, and tutors can support both.

One challenge for students, however, is managing these multiple sources of feedback as they revise. Although our workshops and course materials emphasize program goals and objectives, we can never ensure that feedback will be consistent between a tutor, the instructor, the scorer, and a peer. One of the most common concerns we hear from students, in fact, is that a tutor in the writing center suggested something different than a scorer or their instructor. To help students negotiate this, scorers provide a heuristic at the end of each set of comments that help students understand the suggestions, compare them, and create a plan for revision. Materials in the program ebook also help students navigate different feedback responses. Although this can be frustrating, we hope that students will learn to negotiate feedback and apply that ability to their future writing projects. Wilson (2006) stated that

by placing the onus on the writer to sift through conflicting judgments, we are asking writers to peel back the layers that create our assessments. Although our acceptance of disagreement has opened the door to subjectivity, our shift from agreement at all costs allows us to deal head-on with the nature of how readers interact with writing—its rhetorical effect and purpose. In this way, our assessments and instruction acknowledge the complexity of the writing process. (p. 63)

Furthermore, as much as we work for consistency, we also recognize that for students to address a realistic audience, part of our focus on transfer requires that we avoid providing writers with a “one-size-fits-all-readers” approach to audience, “and instead enable them to navigate the multiple reading roles that they will likely encounter as communicators in various disciplinary and professional contexts” (Reiff, 2002, p. 104).

Some students may feel challenged by managing an excess of feedback, and may be frustrated by not having that singular voice of authority regarding their writing. In other words, they would prefer that their instructors provide the evaluation of their projects. Rebecca Rickly (2006) discussed student frustration at Texas Tech University, noting that

students who normally benefited from the more subjective cohort model were, they thought, disadvantaged by the lack of a relationship with the teacher. Showing eagerness, being prepared, speaking out in class, and simply “working hard” did not influence their grades, and many who had relied on these strategies in the past felt frustrated. (p. 194)

Similarly, each semester at UTEP, a handful of students express frustration through surveys or course evaluations. One student response reflects a complaint heard several times: “Having to deal with a third-party for grading seems to be pointless in the sense that you have no way of communicating with the committee.” We are hopeful, however, that students will continue to learn from the experience of writing for an unknown audience, whether they “liked” it at the time or not. The likelihood of students encountering similar writing circumstances encourages and guides us, as we see students in large-capacity classrooms writing for an instructor, but graded by an unknown teaching assistant with whom they have no relationship. And, again, the program is able to use this student feedback to improve instruction so that students have a fuller understanding of why MinerWriter is used in first-year composition at UTEP and how it can contribute to their growth as writers.

To provide one last opportunity for feedback and to address a variety of student concerns, we instituted a grade appeal process. In this process, a student must articulate precisely what concerns they have and how the score and comments on the rubric do not accurately reflect the quality of their project. Instructors who are not on the Scoring Committee serve as the review readers, again expanding the extent of feedback students can receive on their projects.

Continuous Programmatic Feedback and Improvement

The technology employed for evaluation and assessment has afforded the opportunity for continuous, and immediate, feedback into the program. Unlike a typical programmatic assessment that occurs in the summer, often with a gap of months between the time of the assessment and the start of the next semester, MinerWriter provides the opportunity to evaluate many aspects of the program almost immediately. We can uncover student struggles, and then plan interventions, address them at a workshop, or quickly share them on the program wiki.

With insight that accumulates over the entire semester or academic year, the program is able to assess where students did well and where they struggled on every major assignment. We can then make adjustments to the assignments and scaffolding as needed. We can also determine where the rubrics are too easy, too challenging, or unclear. For example, students initially struggled with the purpose of the Genre Analysis assignment, and their grades suffered significantly because the rubric was heavily weighted toward analysis of genre, not the arguments concerning the topic of these genres. The following semester, we suggested adjustments for instruction and revised the assignment and scaffolding in the ebook. We also added heuristics that helped students stay focused on analysis of the genres and not become distracted by their argument on the subject. With this additional instruction, we scaled back the weight on the rubric. This example illustrates how closely the assignments and rubrics are integrated and meant to inform one another. Additionally, it shows how the program is able to continuously improve and tailor the curriculum to the local context.

FYC@UTEP also takes advantage of the opportunity to assess the assessment: the rubrics and norming process. Because we do not assume that the rubrics and assessment should drive the curriculum, we pay close attention to the places where students struggle and where instructors and/or scorers express confusion. Several times the rubric required clarification or adjustments; for example, ethos is a category of each rubric and usually involves the quality of sources and the fair use of those sources. However, it can be difficult to decide on the language of the rubric when both “ethos” and “research” are categories on a rubric. Does quality go with ethos? Yes, but it also applies to research. Over time, the language of the rubric has been refined to guide scorers into these distinctions, and during norming discussions we delineate which attributes should be addressed in each category. This ensures that the projects are evaluated consistently and aren’t “double dinged” across the rubric. Additionally, each semester, we review the norming process and make adjustments as appropriate. For example, because the Directors and Team Leaders were fielding many individual questions that could also be teachable moments for the whole group, online discussion areas were created to encourage community building and consensus among the scorers. Another adjustment included more integration of the graduate seminar on composition theory and pedagogy with the commenting and grading processes. This change helped new teaching assistants to understand that grading is not just TA work, but that it is part of the larger project of teaching writing. It also helped them learn how to coach students into reaching course learning goals and objectives whether tutoring in the writing center, commenting on student projects, or teaching a class.

Clearly, what we found is that distributed digital assessment creates a rich body of data that provides feedback to each part of the composition program—the curriculum, assessment, delivery, graduate student preparation, professional development, and student achievement. The program has created a process of continuous feedback and revision so that all people involved in the process can work most efficiently and effectively and so that we can offer the best possible instruction to composition students.

ADDITIONAL BENEFITS AND CHALLENGES OF DIGITAL ASSESSMENT

Because of the many redesign aspects of FYC@UTEP, there were additional benefits to the university as a whole. Individual instructors were no longer spending as much time commenting on and evaluating student drafts and final projects, and we were able to increase class size by five students. By raising caps in combination with hybrid instruction, the program was able to reduce the number of classrooms required to teach composition. This additionally enabled us to schedule nearly all our second-semester classes and many of our first-semester classes into just four computer classrooms. This provides nearly all students in approximately 80 sections with access to the technology the course requires. It also decreased the number of part-time faculty required each semester. By decreasing that number, the program not only saves money, but it is also able to ensure that the adjunct instructors are the most highly qualified.

The digital curriculum and assessment system has enabled the program to “go green.” Students submit electronic projects; all assignments, rubrics, and scaffolding are included in the ebook; and norming sessions utilize Blackboard. Considering the amount of paper 4,500 students who passed through our courses annually once used, the reduction in paper is significant. As mentioned previously, the program textbook, The Guide to First-Year Composition, is now electronic. Published for many years, this has taken the form a supplemental workbook. Although it had always been useful, it was limited in effectiveness due to variable instructional methods and assignments, price-dependent page constraints, and the massive effort it took to revise. The electronic version is easier to revise, and the lack of a page restriction encourages us to increase the amount of scaffolding. Because it is an ebook, we continue to improve it by gradually moving from text-only PDF to a document with design features, web links, and, most recently, embedded videos and podcasts.

In terms of challenges, buy-in was our first. Change may be inevitable, but it isn’t always welcome. At first glance, the evaluation and assessment program was perceived as threatening and instructors experienced what Fred Kemp (2005) so appropriately labeled “the psychology of loss,” which describes a “universal acceptance of the advantages. . . [felt] by nearly everyone but the teachers. . . who have been teaching in the traditional ‘self-contained classroom’ mode (emphasis ours, p. 108). However, the full-time faculty came together to develop the program goals of transferring rhetorical strategies and skills sets, of creating assignments that help students learn and test transferable strategies and skills, as well as of articulating the standards by which these are assessed. We wrote the mission statement, and we tailored this assessment program to fit the institutional context. Buy-in has been achieved through invited ownership, and over time, graduate students and part-time faculty have participated in the revision of the ebook and supporting materials. However, this is not to say that all faculty in the program fully support the assessment system. Concerns generally center on the lack of perceived authority granted by the giving of grades as well as conflicts that may arise between what is taught in class and how the projects are evaluated. This last concern is voiced by both the instructors and members of the Scoring Committee, but, ultimately, it is the rubric and assignment that guide evaluation and assessment.

An evaluation and assessment program that provides a wealth of useful data should be considered a huge advantage, particularly for a composition program that historically has not collected much data. It provides opportunities to make clear, supported arguments to university administration, and it enables us to seek funding opportunities. For example, as we compile data showing success in terms of pass rates, we can argue for more instructional computer space and updated software along with training and technology support. As we show how well we utilize the rooms, we not only provide an example to other departments, but we also maintain first rights to scheduling the prized computer classrooms. Furthermore, we have been able to argue for increases in salaries and are hiring more full-time lecturers to maintain a consistent level of experience and mentorship for the graduate student scorers and instructors. We have also been able to increase the hiring of graduate students at the Master’s level. We apply some data immediately and organically to instruction and to the revision of assignments, rubrics, and the norming process. The data helps us identify scorers who have difficulties applying criteria or understanding concepts and to plan mentoring strategies as the scorers move into teaching the following year. Our data also helps us evolve in ways that remain within our objective of teaching transferrable rhetorical strategies and skills sets.

However, managing the data beyond these tasks is another challenge the program experiences; we have more data than a composition program could hope for, and additional collection and analysis provides numerous avenues of research were there time to pursue it. But, without a clear vision of how these avenues can be managed, analyzed, or applied, the data can become unwieldy. To be fair, the day-to-day tasks of the program simply do not allow for the time needed to complete deep analysis. Thus, a struggle is to balance the data and our desire to use it intelligently along with the time we have available.

A final challenge presented with this evaluation and assessment system is the amount of time and expertise it takes to do it well. Maintaining the system, preparing the Scoring Committee to do the commenting and grading, and preparing the instructors to teach the course effectively take the efforts of several people in the program. We strive to have two to three experienced instructors who serve as training leaders and support for the assessment advisor. In addition, a second year PhD student serves as a junior assistant director. Of course, the issue of compensation must also be faced, and we generally offer course reductions for those who serve in assessment and training. Although we have experienced some reluctance to participate in what is clearly a time-consuming task, the benefits of working and learning together have proven to be a valuable lure.

CONCLUSION

The field has made great strides toward digitizing first-year writing curricula and delivery, but more research and scholarly attention must be paid to assessing student multimedia work effectively and according to their targeted discourse communities. Neal (2011) said that “we have this opportunity, while the texts and technologies are relatively new, to reframe our approaches to writing assessment so that they promote a rich and robust understanding of language and literacy” (p. 5). He is right. Students, their writing habits, and their writing worlds are evolving, so we too must evolve in the most thoughtful and productive ways possible. Programs can prepare students for the future they surely face, or the past their instructors may lament. The digital evaluation and assessment system employed by FYC@UTEP affords the opportunity to improve instruction at the local level and provides a model for programs and compositionists to consider when evaluating writing programs. While we realize that electronic distributed assessment is not for every program, we hope that this approach will encourage programs and instructors to create their own forms of assessment that will best serve students in the 21st century.

![]()

NOTES

1. The project, #271984-1 “Digital Writing Assessment: Programmatic Assessment in the Classroom,” was approved by the University of Texas at El Paso IRB on October 12, 2011. We would like to thank Sara Bartlett Large and Marcos Herrera for demonstrating the process of using MinerWriter as well as Maria Dominguez from UTEP’s Instructional Support Services for her expert help with the captioning. ↩

2. ICON stands for Interactive Composition Online, and was enabled by database-driven web software written at Texas Tech. As described by Kemp (2005), “students turn in their documents through Web browsers, do their peer critiquing online, and receive their comments and grades online. The database manages the huge distribution of student writing, critiquing, grading, and professional commenting” (p. 107). Recently, Texas Tech moved to an system they developed called Raider Writer; for a detailed discussion of the re-vision/re-creation process see Hudson and Lang (in press).↩

3. As we evaluated the previous curriculum, we learned that for many semesters, the most commonly received grade in the second-semester course was an A. In contrast, the average grade given since implementing the digital assessment system the redesign was a B. While the program certainly wants students to succeed, it also needs to provide a rigorous curriculum and an unbiased evaluation system. (For more discussion on electronic distributed evaluation/assessment and grade inflation, see Brunk-Chavez & Arrigucci, 2012).↩

4. The program redesign was funded by a Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board Program Redesign Grant and facilitated in part by the National Center for Academic Transformation. ↩

5. The instructor evaluates the remaining 30%, and the final grade is assigned by the instructor. This helps appease some student concerns over the instructor not being able apply elements such as participation to their final grade (see Brunk-Chavez & Arrigucci, 2012). ↩

6.UTEP is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS). SACS requires that instructors of record have at least 18 hours of graduate credit in the discipline they will teach before they teach an FYC class. ↩

7. We extend invitations to composition faculty to attend these sessions, and those who do report that the sessions are very valuable. ↩

8. Other workshop topics included teaching primary research, working with L2 writers, teaching hybrid courses, and using rhetoric and composition studies scholarship in the course, for example. ↩

![]()

REFERENCES

Broad, Bob. (2003). What we really value: Beyond rubrics in teaching and assessing writing. Logan: University of Utah Press.

Brunk-Chavez, Beth, & Arrigucci, Annette. (2012). An emerging model for student feedback: Electronic distributed evaluation. Composition Studies, 41, 60–77.

Camp, Roberta. (2009). Changing the model for the direct assessment of writing. In Brian Huot & Peggy O’Neill (Eds.), Assessing writing: A critical sourcebook (pp. 102–130). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Council of Writing Program Administrators (2000, April). WPA outcomes statement for first-year composition. Retrieved from http://wpacouncil.org/positions/outcomes.html

Elliot, Norbert. (2008). On a scale: A social history of writing assessment in America. New York: PeterLang.

Gaver, William. (1991). Technology affordances. CHI Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: Reaching through technology (pp. 79–84). Retrieved from http://www.cs.umd.edu/class/fall2002/cmsc434-0201/p79-gaver.pdf

Garfield, Joan. (1994). Beyond testing and grading: Using assessment to improve student learning. Journal of Statistics Education, 2 (1). Retrieved from http://www.amstat.org/publications/jse/v2n1/garfield.html

Herrington, Anne; Hodgson, Kevin; & Moran, Charles. (2009). Technology, change, and assessment: What we have learned. In Anne Herrington, Kevin Hodgson, & Charles Moran (Eds.), Teaching the new writing: Technology, change, and assessment in the 21st-century classroom (pp. 198–208). Berkeley, CA: Teachers’ College Press.

Hudson, Rob, & Rickly, Rebecca. (In press). Redevelop, redesign, and refine: Expanding the functionality and scope of TOPIC into Raider Writer. In George Pullman & Baotang Gu (Eds.), Designing web-based applications for 21st-century writing classrooms.

Kemp, Fred. (2005). Computers, innovation, and resistance in first-year composition programs. In Sharon James McGee & Carolyn Handa (Eds.), Discord and direction: The postmodern writing program administrator (pp. 105–122) Logan: Utah State University Press.

Neal, Michael R. (2011). Writing assessment and the revolution in digital texts and technologies. New York: Teachers College Press.

Ong, Walter J. (1975). The writer’s audience is always a fiction. PMLA, 90, 9–21.

Pachler, Norbert; Bachman, Ben; & Cook, John. (2010). Mobile learning: Structures, agency, practices. New York: Springer.

Reiff, Mary Jo. (2002). Teaching audience post-process: Recognizing the complexity of audiences in disciplinary contexts. WAC Journal, 13, 100–111.

Rickly, Rebecca. (2006). Distributed teaching, distributed learning: Integrating technology and criteria-driven assessment into the delivery of first-year composition. In Kathleen Blake Yancey (Ed.), Delivering college composition: The fifth canon (pp. 183–198). Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Selfe, Cynthia. (2004). Students who teach us: A case study of a new media text design. In Anne Frances Wysocki,

Johndan Johnson-Eilola, Cynthia Selfe, & Geoffrey Sirc (Eds.), Writing new media: Theory and applications for expanding the teaching of composition (pp. 43–66). Logan: Utah State University Press.

Smith, William. (2009). The importance of teacher knowledge in college composition placement testing. In Brian Huot & Peggy O’Neill (Eds.), Assessing writing: A critical sourcebook (pp. 179–202). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

White, Edward M. (1996). Power and agenda setting in writing assessment. In Edward M. White, William D. Lutz, & Sandra Kamusikiri (Eds.), Assessment of writing: Politics, policies, and practices (pp. 9–24). New York: Modern Language Association.

Wilson, Maja. (2006). Rethinking rubrics in writing assessment. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

![]()

Return to Top

![]()