Black Narratives Matter: Pairing Service-Learning with Archival Research in the Literacy Narratives of Black Columbus Project

CYNTHIA L. SELFE & H. LEWIS ULMAN

ABSTRACT

This chapter explores an oral history model for service-learning through The Literary Narratives of Black Columbus course. In the course, students assist African-American community members in Columbus, Ohio as they audio- or video-record autobiographical accounts of their literacy practices and values, and preserve these narratives in the DALN. In the process, students learn how to interview participants; record and edit texts; analyze qualitative data; document and archive primary sources for public access; design archival materials for wide accessibility (e.g., transcribing and captioning audio and video); report research findings; and design projects that provide reciprocal benefits to students and community participants. These characteristics link the course with the goals and practices at the heart of the DALN, allowing us to provide students a range of learning opportunities, while contributing to the community an invaluable historical record of African-American literacies, told in community members’ own voices. The chapter includes insights and recommendations for further community-oriented, DALN-based pedagogical projects.

***

Introduction

The Literary Narratives of Black Columbus project (LNBC) employs an oral history/archival model for a service-learning project at the core of a second-year writing course offered at The Ohio State University. During the course, students assist African-American members of Columbus, Ohio communities in audio- or video-recording and preserving narratives about their literacy practices and values in the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives (DALN). In the process, the students learn about and practice interviewing techniques; digital media recording and editing; cataloging and archiving primary sources for public access; designing archival materials for wide accessibility (e.g., transcribing and captioning audio and video); searching digital archives; analyzing qualitative data in general, and personal narratives in particular; reporting research findings in essays and oral presentations; and designing service-learning and oral history projects that provide reciprocal benefits to students and community participants. Chief among the contributions of this course, we believe, is the fact that students learn to become field researchers who document and preserve the first-hand accounts of the literacy practices and values of African-American citizens, a project of considerable historical, cultural, and personal value.

The DALN is a publicly available, online archive of personal narratives about individuals’ literacy practices and values. These literacy narratives are recorded in a variety of formats (text, video, audio) under various circumstances, but are most often written or recorded in private or told to a single interviewer (university students, in the case of the LNBC), who may interact with the storyteller in various ways, ranging from silent listener to more active interlocutor. This constellation of characteristics links the DALN and the LNBC project closely to the goals and practices of oral history and to the archival turn in rhetoric, composition, and literacy studies.

To begin, it might be best to specify what we mean when we use the terms literacy and literacy narratives. With the term literacy, we refer to a broad range of reading and composing practices, activities, and events that take place both online and offline and are always situated in dynamic and fluid social systems, laden with rhetorical choices and shaped by “historical circumstances, individuals’ lived experiences, and particular situations for writing” (DeRosa, 2002, p. 3). Literacy practices, events, and values, as we understand them, are related in complex ways to existing cultural milieus; educational practices and values; social formations such as race, class, and gender; political and economic trends and events; family practices and experiences; technological media and material conditions—among many other factors. As the work of Brian Street (1995), James Gee (1996), Harvey Graff (1987), and Deborah Brandt (1995, 1998, 1999, 2001) reminds us, we can understand literacy as a set of practices and values only when we properly situate these activities within the context of a particular historical period, a particular cultural milieu, and a specific cluster of material conditions. This understanding informs everything that happens in the LCBN course.

When we use the term literacy narrative, at the most general level, we refer to personal stories and first-hand autobiographical accounts of reading and composing activities, events, values, and understandings, composed of selected details for a rhetorical purpose. James Phelan, for instance, defines narratives as “somebody telling somebody on some occasion and for some purpose that something has happened” (Phelan & Rabinowitz, 2005, p. 323). In this sense, literacy narratives should not be understood in terms of their value as either true or fictional accounts, but rather in terms of the representational effort authors undertake to understand and represent the literacy practices, events, and values in their lives. As Phelan (2013) notes, the purpose of such narratives is to make sense of personal experience:

[S]torytellers seek to come to terms with their experiences with various forms of literacy as a way of understanding who they are now, why they did what they did and do what they do, what they might do next, and so on. Indeed, what’s at stake for these storytellers is precisely the act of understanding the effects of events, people, places and other phenomena that they encountered rather than invented. That these acts of understanding inevitably entail interpretations rather than objective recordings highlights narrative’s capacity to make sense of experience. That the same storyteller might revise her narrative does not render both versions fictional. Instead, it underlines the point that understanding one’s life and one’s identity is itself an evolving process.

Moreover, an archive of such narratives provides a multivocal record of collective identity and difference along various axes of shared and contrasting experiences, and the LNBC project aims to introduce students to the construction and study of a multimodal, digital archive of such narratives. Most work on the archival turn in rhetoric, composition, and literacy studies focuses on the intellectual and ethical challenges faced by professional researchers working with historical archives and contemporary oral history projects (Wells, 2002; McKee & Porter, 2012; Carter & Conrad, 2012; Gaillet, 2012), and some notes the work of “author-users” contributing to contemporary digital archives (Purdy, 2011). In addition to researcher and writer, students enrolled in our service-learning course enact an additional archival role: oral history field researchers helping diverse members of Columbus’s Black community record and preserve the personal narratives they contribute to the DALN.

Service-Learning

From the early days of our work with the DALN as founding Directors, we considered the archive a potential focus for service-learning courses, especially because such courses typically extended beyond the walls of conventional classrooms and out into surrounding communities, as does the DALN. At The Ohio State University in the City of Columbus, such an approach afforded students and teachers new ways of thinking about where and how the teaching and learning of literacy happens, new perspectives from which to consider the tools and approaches that support literacy practices and events. Both of these expanded understandings were central to the DALN as we originally designed the archive.

On one level, the version of service-learning which came to influence our efforts to use the DALN was shaped by a respect for the lives of the Black community partners, contributors, and organizations that we hoped would become involved with the archive. This perspective—which later informed the Literacy Narratives of Black Columbus course itself—is characterized most clearly, perhaps, by service-learning pioneers such as Robert Sigmon (1979), who argued that service-learning efforts should be guided by the following principles: that (a) those being served controlled the services, (b) those being served become better able to serve themselves and others, and (c) those who serve learn and have certain control over what is to be learned (p. 10).

On another level, as teachers, we also felt that credit-bearing service-learning courses like the LNBC class that we wanted to design should take into account students’ educational needs. As the Commission on National and Community Service (1993) noted, experiences through which students participated in carefully planned and organized service experiences were “coordinated in collaboration with school and community”; integrated into students’ academic curricula and offered them time to “think, talk, or write” about the service activity; provided students opportunities to use “newly-acquired skills and knowledge in real-life situations”; and enhanced “what is taught in school by extending student learning beyond the classroom” and fostering a “sense of caring for others” (p. 15). In the case of the LNBC course, we wanted Ohio State students to get out of a conventional classroom and learn more about the citizens of Black Columbus communities that characterized the city. We also wanted students to write about what they learned as they interviewed these citizens.

Further, in balancing these differing perspectives, as Paula Mattieu (2005) suggests, we also tried to avoid “institutionalizing” the relationship between 1.) the university that employed us and also funded and supported the DALN as an intellectual project, and 2.) the community members we hoped to serve with the work of the archive. On this dimension, we tried maintain a “rhetorically responsive engagement” with a set of generous Community Partners when we taught versions of our service course, individuals who could serve as liaisons with the communities, organizations, and neighborhoods they represented; who were willing to help us understand the many dimensions of such communities; and who were able to bring students into contact with differing populations and groups. Our goal with these liaisons was to forge a dynamic understanding of partnerships that would acknowledge the “ever-changing spatial terrain” and “temporal opportunities” of such efforts while retaining a value and focus on the “voices of individuals” (Mattieu, 2005, p. xiv). In this work, Black artists in Columbus provided entrées into poetry slams and jazz clubs, Black educators opened the doors to their classrooms, and Black pastors introduced students to their congregations.

Another goal in working with Community Partners was to forge what Sean McCarthy (2012) and other scholars (Long, 2008; Parks & Goldblatt, 2000) describe as a relational understanding of service-learning in which composition faculty engage with community partners, whenever possible, in tactical efforts to leverage university resources—such as service-learning classes and the DALN—for the benefit of communities, neighborhoods, and organizations. The LNBC course, for example, used university equipment and facilities to teach community partners how to record literacy narratives with digital recorders and edit these narratives on computers with inexpensive software. One version of the course also provided an impetus to upgrade the networking in the Community Extension Center’s classroom lab.

We began the formal process of designing the LNBC course in 2008, encouraged by a website of OSU’s Community Extension Center (a neighborhood center established and run by the African and African American Studies Department), which cited the need for histories of Black neighborhoods created by local community members in their own words. We met with Ms. Carla Wilks, Senior Project Manager, to design a service-learning course that would be open at no cost to community members—some of whom would agree to serve as Community Partners and liaisons—and, at the same time, enroll undergraduate and graduate students from OSU. This course would involve small teams of students (composed of a graduate student team leader and several undergrads working with a Community Partner) in helping community members record their own literacy narratives using digital video and audio equipment, and preserve these narratives in the DALN. Community members in the class would benefit by learning to use digital video and audio recording equipment, edit the narratives they contributed, and preserve these narratives for posterity by uploading them to the DALN. In doing this work, community members would also be composing a history of their neighborhoods, community organizations, and families in their own words and for their own purposes. For the benefit of their community, these community members would also be composing a series of narratives (Ladson-Billings, 1995, 1998, 2005) that countered dominant cultural narratives and media representations of Black Columbus neighborhoods as sites characterized primarily by poverty and violence.

The students in this class helped community members record and contribute their literacy narratives and, at the end of the course, analyzed these narratives for useful insights about literacy and reflected on what they had learned through their interaction with community members and Community Partners. Both graduate and undergraduate students benefitted from learning interviewing skills and research/analysis methods, learning about the many literacy practices and values of community members, identifying the issues and “critical incidents” (Clifton, Long, Roen, 2013) that marked the lives of community members, and encountering narratives that ran counter to dominant stereotypes. They also enjoyed helping to compose the autobiographical text of African-American history in Columbus communities through the stories of individuals. Graduate students—who came generally from the Department of English or from the College of Education and Human Ecology at Ohio State—benefitted from learning how to conduct field research, lead a research team, and put their theoretical understandings (of composition studies, narrative theory, linguistics, education, and critical race theory) to the test of practice.

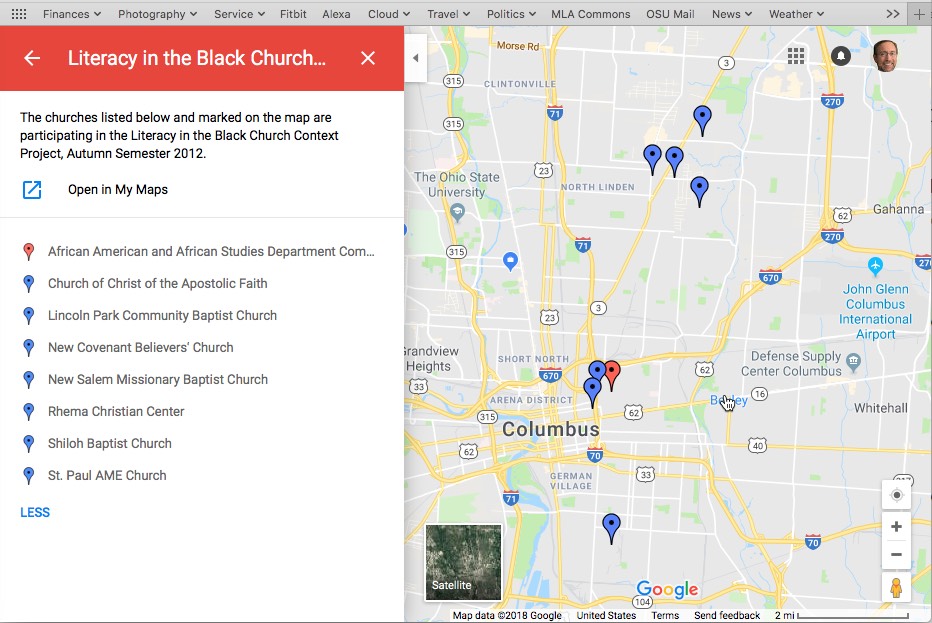

The course included several elements that helped students reflect on their relationship to Columbus’s African-American community in their multiple roles as field researchers, archival researchers, and writers. First, we stressed that students were helping the community define the archive as a living exercise in self-definition rather than an historic storehouse of information selected by others or for other purposes (Gaillet, 2012, p. 39). Second, because most of the students were not members of Columbus’s African-American community, we invited members of the community to initial class meetings to help students learn about the community with whom they would be working (Gaillet, 2012, p. 42). For instance, three pastors of local Black churches discussed their congregations’ histories and missions within the context of the Black Church in the U.S., and they introduced students to the format and structure of African-American call-and-response patterns in pastor-congregation exchanges in their churches (see Fig. 1).

Finally, each class included a Community Sharing Night (see Fig. 2) at which dinner was served to community members, and Community Partners and student teams reflected on what—and how—they had learned from their experience over the semester, thus providing a degree of transparency and accountability for the many ethical and sense-making choices involved in archival research (Gallet, 2012; Carter & Conrad, 2012).

For example, in two of the classes involved in the project, teams of students created “digital exhibits” (also included in Appendix) in which they reported their observations about the literacy narrative they helped community members record and related those observations to background reading.

The students summarized their exhibits during the Community Sharing Night and responded to questions from members of the community before submitting final versions of the exhibits. In another class, at the suggestion of a community member who noted that some members of his congregation might not find it easy to access the narratives via the DALN, students curated short clips from narratives which, along with direct links to the entire narratives on the DALN, they incorporated into a “community sampler” website (also included in Appendix) that was shared at the Community Sharing Night, online, and on DVDs presented to the congregations.

In subsequent years, this course focused on different Black Columbus communities, working with Black library users, Black jazz musicians, poets, dancers, senior community members, church pastors and congregation members, LGTBQIA community members, Somali immigrants, artists, and housing project residents. By 2015, approximately 300 narratives had been contributed as part of the Literacy Narratives of Black Columbus (LNBC) course.

The syllabus, handouts, assignments, and approaches for this course are detailed in an iTunes University course, Documenting Community Literacies: Using Digital Narratives, and can be adapted for use in a range of courses and disciplines (see Video 1).

|

|

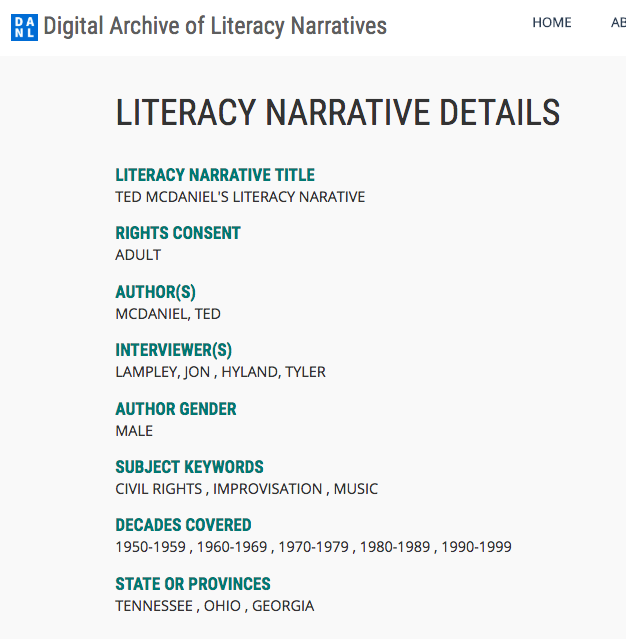

Oral History/Life History

We have also realized the value of the DALN as a resource for teaching about—and learning through—oral history and life history research methods, approaches that are often of great interest to scholars who undertake qualitative investigations in the fields of composition studies and education. This methodological work has been inspired, in part, by Deborah Brandt’s (2001) scholarship and grounded in oral-history and life-history approaches (Bertaux, 1981; Bertaux & Thompson, 1993, 1997; Thompson, 1988; Lummis, 1987). The DALN is well suited to such work because its rich metadata protocol encourages contributors to identify not only a historical context using the author’s age and the year(s) on which a narrative focuses (which can be used to connect narratives or authors dealing with a similar historical period), but also to locate authors and narratives by geography (thus, identifying stories from related regions and locations), articulate a topical focus (which can be used, in connection with dates, to identify patterns and trends characterizing a moment in history), identify the author’s gender (which can be used to explore critical incidents inflected by gender at various points in history and locations around the world), and select key words (that can be used, in connection with geographical and age data, to link individual narratives to other narratives from people in a birth cohort and country). Such metadata is included by the author only if he/she so desires to include it, but where it exists, rich metadata facilitates complex queries (see Fig. 3).

Because the DALN links individual literacy narratives to metadata that situate these accounts in specific historical, economic, and socio-cultural contexts, we can use the archive to teach students both how to conduct life history interviews and how to analyze a set of narratives related by life-history connections. As part of their work with the DALN, for instance, students at OSU often begin by identifying a population of individuals of interest to them—for example, Mormon men over 50, Autistic self-advocates who engaged in online activism during the first decade of the 21st century, Black women in their 20s who use computers as writing and communication tools. During such projects, we talk to students not only about how to record interviews focused on the literate lives of individuals (Black educators, Black jazz musicians, Black library patrons, Black poets), but also why it is important to encourage storytellers to identify and attach relevant metadata tags to their narratives (“school,” “jazz,” “libraries,” “poetry”), thus situating their literacy activities and practices within the context of age and gender groupings, geographical (“Columbus,” “Ohio”) and institutional (“2nd Baptist Church,” “Martin Luther King branch of the Columbus Metropolitan Library,” “Zanzibar Poetry Club”) populations, and historical periods (“Civil Rights in the 50s and 60s,” “contemporary Columbus”) that have shaped their experiences.

Because these metadata protocols structure the DALN, students and scholars can also use the DALN to identify and access the literacy narratives of a life-history cohort. The DALN proves useful in providing researchers ready access to a range of literacy narratives that have already been contributed by particular birth cohorts (for instance, Deaf women in their 40s and 50s or composition teachers who had been teaching for 20 years). Because the DALN is available as a public archive and accessible online, these interviews are available for such uses under the terms of their contributors’ choosing (either a Deed of Gift granted to the DALN or a Creative Commons License), thus providing researchers the opportunity to explore populations of interest and practice cohort analysis, focusing on literacy experiences, events, literacy values, or critical incidents shared by cohorts as part of what Norman Ryder (1965) calls “their unique location in the stream of history” (qtd. in Brandt, 2001, p. 11).

An example of scholarship that relies on life-cohort approaches appears in Stories That Speak to Us, a collection of curated exhibits from the DALN published by the Computers and Composition Digital Press (CCDP). “Claiming Our Place on the Flo(or): Black Women and Collaborative Literacy Narratives,” authored by Valerie Kinloch, Beverly Moss, and Elaine Richardson (2013), focuses on the life history and literacy narratives of three Black women in their 30s, 40s, and 50s. This curated exhibit consists of short clips taken from longer interviews in the DALN, and explores the ways in which these faculty members both share aspects of their complexly rendered professional identities with other Black women academics and, at the same time, understand those identities as distinctively shaped by their individual circumstances. In their discussion, the three women identify the role of place and role models in their literate lives, discuss those factors that both encouraged and discouraged them to pursue a Ph.D., and talk about the various turning points in their lives. The collaboratively authored essay also sets the participants’ discussion against contextual “canvases” of history, geography, family history, and race relations in the United States.

The community focus of the LNBC project highlights two other important concerns regarding archives of local materials. Too often, such projects do not have the resources to create a sustainable, publicly available archive of the materials. Because the DALN is housed at a public university library and supported by the staff of the university’s online institutional repository, students know that their readers can consult the data upon which they base their interpretations, and that future researchers will have the opportunity to revisit those materials, thus constructing archival oral history research as a potentially dynamic conversation rather than a report based on information to which one’s audience does not have ready access (Carter & Conrad, 2012, p. 90–91).

Personal Narratives about Literacy

In the LNBC courses, we have also used the DALN as a resource for thinking about narrative theory and practice, especially in the context of representing literate lives and practices in educational contexts. In this regard, we have used DALN narratives as vectors for learning more about how people think about and represent their own literacy activities, the teaching of literacy, and the learning of literacy both in school and outside of it. We conceive of these narrative representations as neither truth nor fiction (or perhaps, as both and more than truth and fiction), but rather as rhetorically constructed texts that indicate how individuals understand and represent their own lives and the role of literacy in their experiences.

At this level in the LNBC classes, the DALN narratives help us bring alive our scholarly understandings of personal reading and composing activities, as well as the complex cultural, political, ideological, and historical contexts that shape and are shaped by literate practices and the values associated with them. Such stories, in all their rhetorical constructedness and personally selected detail, help us animate personal and familial literacy values of LNBC class members, reveal the effects our educational practices have on the thinking of these young people, and illuminate personal perspectives and multiple identifications in ways that statistics and experiments simply cannot.

Such narratives, within the context of the LNBC class and other classes as well, are rhetorically powerful accounts through which people fashion their lives and make sense of their world—indeed, how they construct the realities in which they live. These narratives are sometimes so richly laden with information that conventional academic tools are inadequate to the task of discussing the narratives’ power to shape identities; to persuade, reveal, and discover; and to create meaning and affiliations at home, in schools, communities, and workplaces.

Part of the reason these narratives are so valuable as representational accounts in the LNBC class (and also in other contexts) is that they “twice encode culture,” as Linda Brodkey (1987) observes: they are simultaneously “practices and artifacts” (p. 46). Because our cultural understandings of literacy are the tropic material of which literacy narratives are woven, even though some narratives affirm and some resist “culturally scripted ideas” about literacy (Eldred & Mortenson, 1992, p. 513), they cannot avoid reflecting, in some way—either directly or indirectly—what it means to read and compose in the cultural lives of LNBC students.

Autobiographical recollection, however, is never quite the same as autobiography (Scott, 1997; Earle, 1972). Thus, when we teach the LNBC course, we remind ourselves that the formulation and telling of literacy narratives is both rhetorically constructed and “weighted with… interpretation” (Lapadat, 2004, p. 113). The storytellers in this course use personal accounts to position themselves within the contexts of their own lives at home, within families, with peers, in school, in communities, and in workplaces. Through narratives, class members connect these contexts to their own understandings and the literate practices of Black Columbus. Because literacy narratives, as we define them here, are autobiographical, they always involve self-representation. Thus, we understand the stories that students and others tell to be sites of both “self-translation” (Soliday, 1994, p. 511) and “redefinition” (Corkery, 2006, p. 69). As LNBC participants tell literacy stories, they also formulate their own sense of self. With each telling, this self changes slightly according to a constellation of social and cultural factors, personal aspirations and understandings, the audiences being addressed, and the rhetorical circumstances of the telling itself, among many other factors.

Our own fascination with literacy narratives in the disciplinary context of the LNBC course has also been shaped by the narrative turn (Daya & Lau, 2007), and particularly what Georgakopoulou (2006) has called a “third wave” of narrative studies that re-situates analysis “from narratives-in-context to narrative-and-identities” (p. 125). In other scholarly contexts outside the LNBC course, such work has been linked to a related contemporary focus on identity in sociolinguistics, linguistic anthropology, discourse analysis, and social psychology, among several other fields (cf. Bucholtz & Hall, 2005; Bamberg, 2005).

Our own perspective on this cultural and academic trend rests in large part upon an understanding that storytelling in the LNBC class and elsewhere is linked in fundamental ways to meaning, knowledge, and identity. Like Michael Bamberg (2005), we avoid a conventional and restrictive focus on cognition alone and gravitate toward an action-oriented study of “language in communities of practice” in the LNBC class, one in which cognition becomes a “product of discursive story-telling,” which he summarizes as, “what people do when they talk, what they do when they tell stories” (p. 215).

For us, as Brett Smith (2007) notes, the contemporary narrative turn is often linked to an increased interest in situated performance (cf. Atkinson & Delamont, 2006; Krauss, 2006; Peterson & Langellier, 2006)—an understanding that has fundamentally shaped the narratives we ask students to contribute in the LNBC class. At least some of the strength in the LNBC course, we believe, derives from the ways in which personal narratives provide individuals with “opportunities to reveal, revise, and reclaim the past” and change their own lives while changing “established accounts and dominant narratives” (Wengraf, Chamberlayne, & Bornat, 2002, p. 254).

The scholarship on narrative theory informed our own thinking and design of the LNBC class not only for undergraduates, but also for graduate students who wanted to extend their understanding of research methods. The recent turn to narrative has inspired a range of research methods based on both formal and informal storytelling events. The Handbook of Emergent Methods, edited by Sharlene Hesse-Biber and Patricia Leavy (2008), for example, identifies a number of research methods that use narratives as central features of inquiry: oral history, narrative ethnography, autoethnography, collaborative ethnography, performance ethnography, interviews, and case studies, among others. For graduate students, the focus on personal narrative as a methodological approach is particularly compelling in the breadth of its application in fields such as folklore, psychology, sociolinguistics, women’s studies, medicine, composition, literary studies, history, art, and cultural studies, among many other disciplines (cf. Brodkey, 1986, 1987; Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2008; Phelan & Rabinowitz, 2005).

We have also come to the understanding—both for undergraduate students and graduate students in the LNBC course— that it is the “inconsistencies, contradictions, and ambiguities” arising from human interaction around literacy narratives, the knots in literacy narratives, that are the most interesting. Literacy is a fundamentally human activity, and as such it is always complexly situated in cultural contexts. For students in the course, these knots reveal the rich weave of literacy practices and values that help constitute human identities. In this way, we discourage students from understanding narratives as “too obvious, challengeable, or immature” (Bamberg, 2005, p. 222).

In the LNBC course, one way in which we help students think about literacy narratives qua narratives is to provide them with different analytical frames inspired by the work of narratives theorists and scholars who focus on narrative accounts. These frameworks offer LNBC students different ways into literacy narratives and the representational information they can yield. For example, we might provide students an analytic framework based on the scholarship of Jennifer Clifton, Eleanor Long, and Duane Roen (2013) that describes the “critical incident” theory approaches to personal narrative accounts practiced by John Flanagan (1954) and Lorraine Higgins, Elenore Long, and Linda Flower (2006).

Approaching literacy narratives from this particular analytic perspective, LNBC students are often asked to listen to/view a set of literacy narratives in the DALN selected from among those of a particular group or population. To analyze these narratives, LNBC students focus on the situated knowledges that individuals bring to the telling of the narratives, identify any shared or common incidents that the storytellers talk about in their narratives, and consider these shared incidents in light of concerns that would benefit from public consideration, discussion, and policy debates. As an example of this kind of analytic work, we have students read “Accessing Private Knowledge for Public Conversations: Attending to Shared, Yet-to-be-Public Concerns in the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing DALN Interviews,” a curated exhibit by Clifton, Long, and Roen (2013) that demonstrates this approach with a set of DALN literacy narratives by Deaf and hard-of-hearing community members.

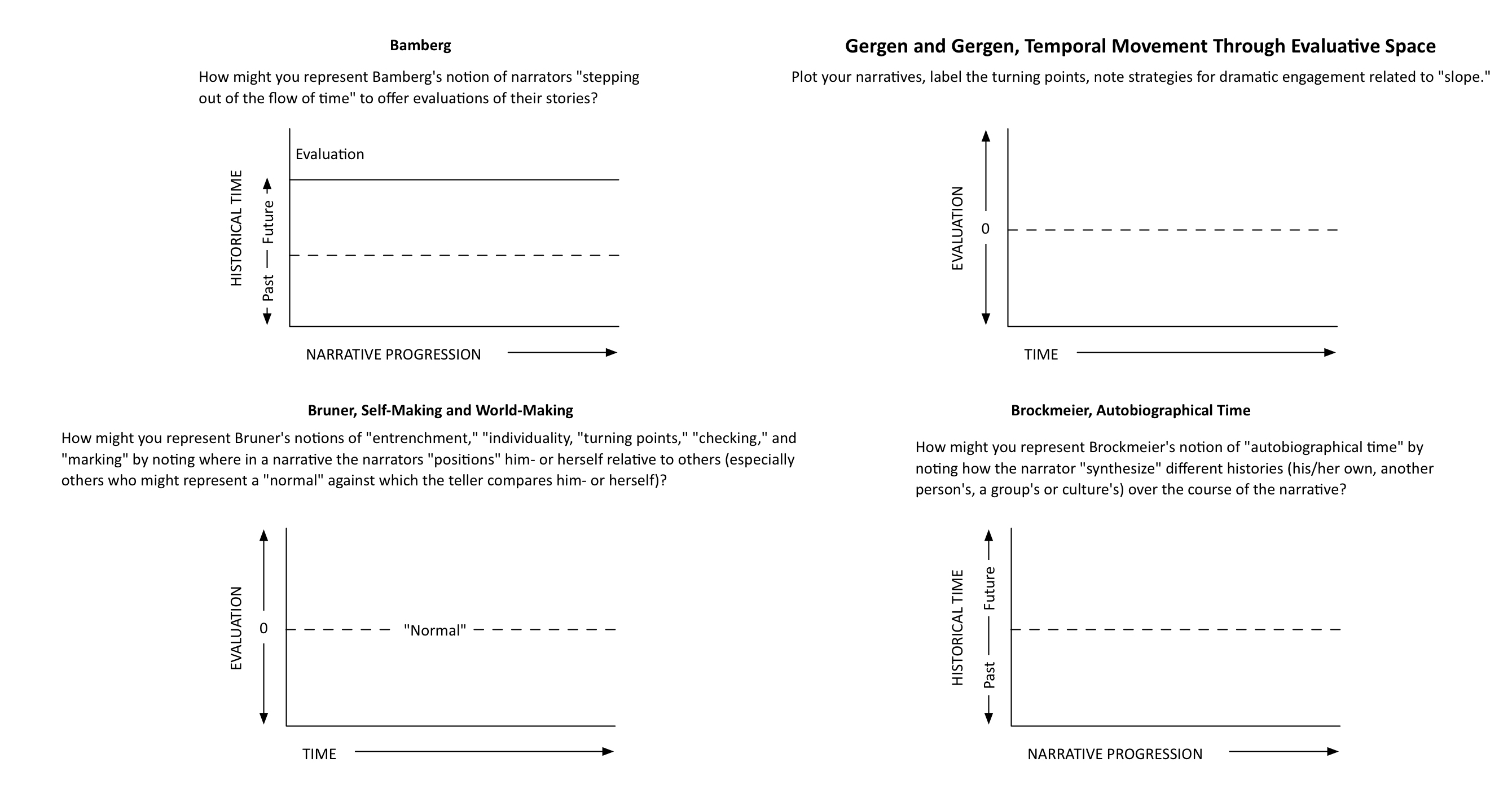

Other analytic frames that we have used for the LNBC course have been derived from the “relational positioning” work of Michael Bamberg (1997) that focuses on the characters with which individuals choose to populate their narratives and their relationships, the concept of “turning points” in the work of Jerome Brunner (2001, 1994, 1991), the concept of “counter stories” derived from scholarship on critical race theory and the work of Gloria Ladson-Billings (1998, 2005), and the patterns of emplotment explored by Kenneth and Mary Gergen (1988). To help LNBC students work with such frameworks, we employ graphs like those used by Gergen and Gergen, adapting them to other scholars’ models of emplotment (see Fig. 4).

Students in the LNBC class are encouraged to understand the DALN as an archive of people and their narratives rather than an assortment of disembodied records or files (McKee & Porter, 2012, p. 77). Students encounter that concept directly in their role as field-researchers, and we try to educate them about how to help contributors reflect on their narratives as “peopled.” Before each recording session, LNBC students discuss with contributors the public nature of the DALN, secure their informed consent to be recorded, and spend some time discussing a contributor’s story. In addition to answering questions about what constitutes a literacy narrative, or how long or short a narrative might be, student researchers in the LNBC course help contributors think about the ethical dimensions of telling stories that involve other people. The DALN values stories about positive and negative experiences with literacy, and to reassure LNBC contributors that they can share negative experiences, student field-researchers are trained to help contributors think about different ways they might tell those stories if they are uncomfortable with the thought of individuals or their families or descendants hearing the story (asking, for instance, whether it is necessary to refer to people by name or to specify time and place).

A further dimension for helping the LNBC students think about the ethics and meaning of the personal narratives they encounter in the DALN (and later in their own interviews with community members) concerns the context in which narrative are composed (McKee & Porter, 2012, p. 67). Because narratives in the DALN were recorded in manifold times, places, and circumstances, and because they are not typically accompanied by detailed information about those circumstances, we encourage student-researchers to practice analyzing the narratives—e.g., the scene and sounds in videos—for information about context, thinking about how this same process will unfold when they ask LNBC community members for personal literacy narratives. As part of such analyses in their preparatory work with the DALN, students might ask questions such as the following:

- In what circumstances was the narrative recorded and collected/preserved, and in what medium? What differences might the circumstances and medium of recording and collection/preservation have made to the composition of the narrative?

- Who was present at the time of composition? What were their roles? How did they interact with the narrator (e.g., as interviewer, audience, technician, researcher, teacher, and so on)? What difference might the audience/interlocutor have made in the composition of the narrative?

- Is the narrative part of a larger group or collection of narratives? What did the narrator know and/or understand about that larger project? How was the project presented to the narrator? How might the larger group affect your understanding of the individual narrative?

Finally, because students in the LNBC class are not required to submit their own narratives to the DALN (they are welcome to do so, but requiring them to contribute literacy narratives would run counter to informed consent), we help them consider literacy narratives not only as archival elements, but also as people-telling-stories-to-other people. In this context, LNBC students work in pairs to tell and record their own literacy narratives, then reflect in writing about their experiences in front of and behind the camera/audio recorder. The student storytellers consider questions like the following:

- How did the story surface in my memory? What initial thought or image fixed my attention on this particular story? What about the prompt or the setting brought it to the fore?

- Have I told this story before? If so, do I think I told it differently this time? How? If not, how did I decide where to begin, what to include, and where to end? Are there details I recall that I am aware of leaving out of this telling? What informed that act of filtering/composing?

And the student interviewers ask themselves questions such as these:

- How did the story surface in my memory? What initial thought or image fixed my attention on this particular story? What about the prompt or the setting brought it to the fore?

- Have I told this story before? If so, do I think I told it differently this time? How? If not, how did I decide where to begin, what to include, and where to end? Are there details I recall that I am aware of leaving out of this telling? What informed that act of filtering/composing?

We hope that engaging LNBC students with all of these dimensions of personal narratives about literacy helps them explore the potential of oral history archives to shape individuals’ and communities’ construction of their own stories.

Exploring Archives of Primary Sources

In keeping with its role as a second-level writing course in the General Education curriculum at The Ohio State University, this course extends the types of research data, ways of analyzing source materials, and formats for presenting analyses that students may have worked with in their first-year writing classes. Notably, our version of the course engages students with primary sources—which “provide first-hand testimony or direct evidence concerning a topic under investigation” (Primary Sources at Yale)—and involves them in the construction of an archive of such sources. In addition to learning how to navigate and search the DALN online to discover relevant primary source material, students help community members record, describe, and submit literacy narratives to the DALN—in effect, creating primary sources for the study of literacy.

As more of our research material moves online, it becomes increasingly important for students to become sophisticated users of online archives. By learning how the data in archives is structured—what counts as an “item,” how each item is described using discrete fields of information that allow for complex inquiry and searches—students will develop greater access to information. By reflecting on the circumstances in which specific primary source materials are created, students develop greater sophistication in posing research questions about those materials. Recognizing the unique nature of each literacy narrative—even if retold, a person’s literacy narrative will change, perhaps in important ways, because of changes in audience, occasion, or the vagaries of memory—provides an opportunity to initiate an ongoing discussion of strategies for ensuring that narratives are not lost, from checking equipment while recording to backing up narratives at various stages in their processing before they are uploaded to the DALN.

In the Literacy Narratives of Black Columbus (LNBC) class, we focus most directly on the nature of archives and primary sources when students first explore the DALN and when they upload community members’ literacy narratives to the DALN. To engage students with the structure of information in the DALN, we often begin the course with a scavenger hunt. First, we demonstrate the various ways of finding narratives in the DALN:

- quick search (a simple text string);

- advanced search using boolean operators (and, or, not) on selected fields;

- browsing the entire DALN by collection, data, author, title, and subject or limiting the scope of browsing using various constraints (e.g., by a range of dates, letters of the alphabet, or text strings).

Next, we review various options for viewing search results:

- sorting by various criteria;

- viewing “simple” or “full” item records—the full item records reveal all of the metadata associated with each narrative.

In order to limit the scavenger hunt to a defined subset of the DALN, teachers can introduce students to “virtual collections” in the DALN associated with projects that have tagged associated narratives with a unique keyword. For instance, all of the narratives connected with LNBC courses can be searched with the keyword “blackcolumbus” (no space).

A typical scavenger hunt prompt might ask student to find the following, either by browsing or searching the DALN:

- A narrative about a topic that interests you

- A narrative that reminds you of your own literacy experiences

- A narrative by a male, female, or transgender contributor

- A video narrative

- A text narrative

- An audio narrative

- A captioned video narrative

- An audio or video narrative accompanied by a text transcript

- A narrative accompanied by an ancillary photo or text file

- A narrative covered by a Creative Commons license

- A narrative covered by a Deed of Gift

These particular prompts encourage students to discover several axes of difference among the literacy narratives preserved in the DALN: subject, medium, content licensing provisions, gender identity, and the presence or absence of supplemental materials beyond a contributor’s literacy narrative. For each narrative that the student finds, we ask students to record the method they used—Browse or search? Quick or advanced search? Keywords?—and to jot down more discursive notes for discussion: e.g., implicit or explicit definitions of literacy in the narratives; literacy practices and values that they share or that were new to them; questions about literacy they would like to explore further; and so on.

Students’ discursive notes about the literacy narratives can kickstart discussion about the nature and diversity of literacy practices and values, but it is also useful to ask students in a service-learning course how the “discoverability” of materials in the archive might contribute to the value of the narratives for the Black Columbus communities with whom they are working. How will LNBC community members find other narratives recorded by members of the community? What more specific searches might students pursue to make sure that contributors can find and use narratives from the LNBC course?

The students’ initial forays into the DALN provide ample evidence of several unique aspects of the DALN and encourage them to think about how the LNBC narratives will fit into the contecxt of the DALN as a collection. Unlike most archives of historical documents—archives created by professional archivists—the DALN employs few fixed vocabularies for the metadata fields found in the full item records. Rather, most metadata is supplied by contributors in their own words, and only one of the metadata fields that contributors are invited to complete (title) is required. So, for example, a narrative associated with the LNBC project may or may not contain information about the contributor’s race/ethnicity in that field, and the information, if provided, may appear in several forms (e.g., African-American, African American, Black) that would not show up in the same search results. These features both complicate and enrich the DALN as an archive (Ulman, 2013b). Searching and interpreting search results is more difficult, but the information in the archive’s metadata provides primary data about how people describe themselves in relation to various demographic categories.

Given these characteristics of the DALN, asking students the following questions after they have completed the scavenger hunt will help them reflect on metadata:

- What terms did people in the community with whom they will be working use to describe their socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender/orientation, nationality, and geographic location—all metadata fields contributors are invited to complete?

- What do the terms mean to the students? What connotations do they carry?

- What other terms might contributors have used? What connotations might different terms have for contributors?

At the other end of the process, when students are helping contributors record their narratives and fill out the DALN information forms, recalling this initial exercise may help them explain the value of the archive and the metadata to contributors and their communities. The exercise may also help impress on students the importance of recording information exactly as contributors enter it on the DALN forms.

As recent work has noted, the metadata and search engines associated with digital archives of contemporary materials have created space for “author-users” like the contributors to the DALN to “determine the terms under which their texts are classified” (Purdy, 2011, p. 39). More generally, thinking about what makes the DALN a complex, structured archive of literacy narratives rather than a simple collection of narratives should help students think critically about the logical structure of any archive they consult.

Qualitative Data Analysis

The literacy narratives in the DALN are largely unstructured (i.e., they do not consist of answers to a set series of questions) and contain diverse information (e.g., stories about individual experiences in various historical and cultural contexts) even when they are connected by a geographical or community focus such as the LNBC project. These oral history narratives can provide rich detail about individuals’ literacy practices and values and help students pose original questions or hypotheses about literacy, generate detailed descriptions of literacy practices and values, and compose rich accounts of patterns they find across narratives. However, students in our classes typically have no experience conducting research on such materials, and without some framework for analysis of literacy narratives, students often fall back on summary.

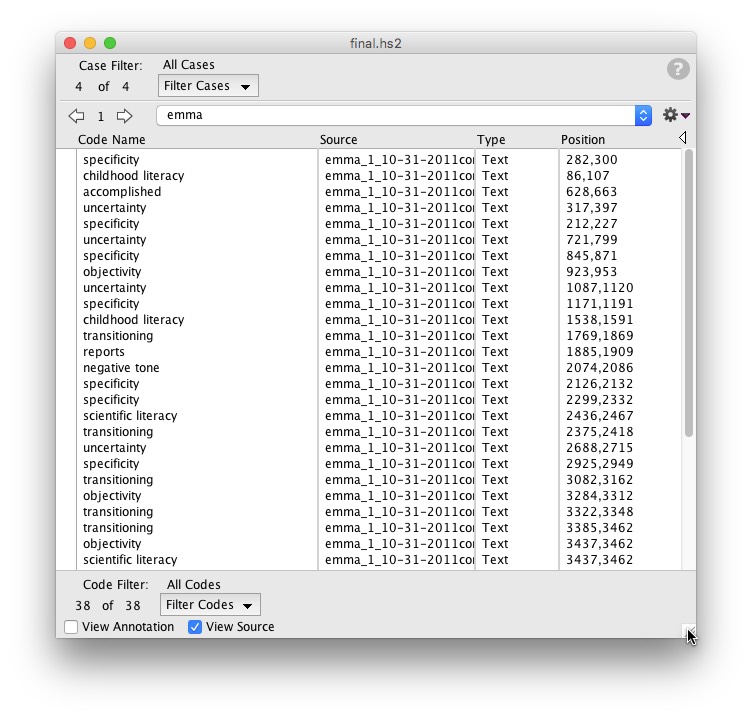

The literacy narratives in the DALN lend themselves to qualitative data analysis methods, and the coding characteristic of grounded theory can help students investigate both the stories recounted in literacy narratives and the manner and circumstances in which they are told. Coding exercises can be conducted as a relatively simple, paper-and-pencil activities or as more structured analyses using free editions of qualitative data analysis software such as HyperRESEARCH (Fig. 5).

However we approach the exercise, the focus of the coding remains on investigating the LNBC narratives rather than formal training in qualitative data analysis. We encourage students to read/view Black community members’ narratives slowly, pausing to note not only details of the story recounted in the narrative (e.g., people and their relationships, settings, time periods, actions) but also aspects of the storytelling (e.g. tone of voice, pace, gesture, language register and code shifting) and details of the interview (e.g., setting, clothing, interactions between the narrator and the interviewer), noting the place in a narrative where each detail appears. For example, in Appendix B, “Education’s Presence in Literacy,” LNBC students Amro Ahmed, Kayleen Faine, and Jacqueline Yurkoski note that one interviewee’s prepared summary “emphasized how education had been instilled in her daily life through her preparedness, articulate words and confidence in her story” (“Teaching”), and how another interviewee’s smile marked a “turning point in the narrative” that marks her focus on music in religious education (“Music”).

In this exercise, we employ a version of open coding (Borgatti), asking students to note aspects of the LNBC narratives (from the list above or anything else that strikes them as important), employing both concrete and more abstract terms (so, for instance, coding mention of a church choir performance both as “choir” and as “music”). Once LNBC students begin to generate a list of code instances (application of a label to a particular section of a narrative), we encourage them to define their codes in writing, reuse them in subsequent narratives as applicable, and pause to record “code notes” in which they reflect on specific contexts in which they use the codes to mark some aspect of a specific narrative. Further, we encourage them to compose “theoretical notes” that connect their reading and coding of literacy narratives to broader contexts—their own experiences, class readings and discussion, or questions about literacy that they would like to investigate further. Spending time working with literacy narratives in this way allows time and space for the archive (and the students as archival field researchers and users) to “resist” premature closure of inquiry (Wells, 2002, p. 58–59). In their introduction to “Education’s Presence in Literacy,” Ahmed, Faine, and Yurkoski exemplify such “open” inquiry when they note that the narratives about literacy in the Black Church (the focus of their LNBC course) that they discuss share not only a focus on education but also a narrative arc that extends from the church to “careers, relationships, or hobbies” (“Introduction”).

Making the Archive Accessible: Transcription and Captioning

Personal narratives recorded in video and audio formats pose limitations for text-based searching on the DALN site and for access by LNBC community members and others with hearing and visual impairments. In keeping with the service-learning focus of the LNBC course, students learn to transcribe audio and video narratives and caption video narratives in order to improve discoverability, access, and analysis not only for community members with visual and hearing impairments but also for all users of the archive. Transcripts make the content of video and audio narratives as well as their metadata discoverable using the DALN’s native search engine and Web search engines such as Google. Transcripts also lend themselves to study with text analysis software, and time-coded transcripts generated from caption tracks can help users quickly find sections of interest in audio and video narratives. Students, too, benefit in several ways from transcribing and captioning audio and video narratives, including opportunities to explore differences between speech and writing and to consider the relationship of paralinguistic features, ambient sounds, and visual elements to the meaning of spoken narratives.

Transcription quickly draws students’ attention to the fact that spoken language does not contain punctuation, paragraphing, or orthography, yet a readable transcription must deal with those conventions. Further, having considered accent, tone of voice, inflection, dialect, pacing, and paralinguistic features—laughter, pacing and pauses, gestures, facial expressions, sounds such as whistling, and so on—during our exploration of qualitative data analysis, students will wonder how to include such information in written transcripts.

For the LNBC classes, we adopt a modified model of “verbatim” transcript that captures a “middle ground” (DeBlasio, 2009) between a polished written text that is easy to read but distorts the character of the original and a complete transcription that contains as much information as possible—including “every single utterance, crutch word, false start, stammer” and preserves “gurgles, burps, coughs, and other assorted verbal expressions” —but is very hard to read (p. 105, 106). This model adopts a standard header that identifies the title of the narrative, if supplied by the narrator, the speaker(s), and the place and date of the recording. Within the transcription, spelling and punctuation follow convention, and paragraphing highlight the structure of the narrative as interpreted by the transcriber. Grammar and diction are not standardized. Speakers, significant paralinguistic features, ambient sounds, and long pauses are concisely described within square brackets. Employing even this simple model provide students with many opportunities to think rhetorically about the structure of personal narratives and the significance of various features of spoken language within specific narrative contexts, a task for which we also enlist specialist visitors to the LNBC class, such as Beverly Moss to talk about the rhetorical patterns and structures of Black Church sermons and Hanif Abdurraqib to talk about the language and images of Black spoken-word poetry (see Text File 1).

Embedding captions in video narratives involves a host of considerations related to their readability (singly and in sequence) on screen, considerations such as screen placement and line breaks that go beyond the focus of this essay, but captioning also raises sophisticated rhetorical consideration, as Sean Zdenek (2011) explores in his rhetorical model of captioning, which “acknowledges the qualitative differences between sound and writing and draws attention to the need for a rhetorical understanding of captioning” and “recasts quality in terms of how readers and viewers make meaning.” Zdenek encourages captioners to consider questions such as the following:

What do captioners need to know about a text or plot in order to honor it? Which sounds are essential to the plot? Which sounds do not need to be captioned? How should genre, audience, context, and purpose shape the captioning act? What are the differences between making meaning through reading and making meaning through listening? Is it even possible, given the inherent differences between, and different affordances of, writing and sound, to provide the same information in writing as in sound?

Asking such questions regarding both transcription and captioning helps LNBC students focus on both general audiences and their immediate audience—members of the Black Columbus communities with whom they are partnering in their service-learning project. In one LNBC course, students learned a valuable lesson about language and identity when one of the community contributors, invited to review her narrative, asked the students to edit their transcript and captions to more accurately reflect her language (see Video 2).

|

|

Revisiting Susan Wells’ earlier discussion of the “resistance” of archives, James Purdy (2011) has noted that digital archives “can resist multimodal texts” because few archives allow us to search directly by sound or image (p. 30). On the one hand, transcription and captioning help lower that form of resistance for member of the community are hearing- or vision-impaired, and, as is the case with many such accommodations, transcription and captioning ease access for everyone. On the other hand, transcription and captioning can help student field researchers and others to resist reaching premature conclusions (Wells, 2002) by deepening their understanding of the unique characteristics of textual, audio, and video narratives.

Learning “Moves” for Writing About Literacy Narratives

Reporting research findings about oral personal narratives will be new to many students. We provide support for students’ composing by adapting the concept of rhetorical “moves” to writing arguments about literacy narratives, designing exercises that build on analytical exercises such as open coding and mapping narrative structures.

This exercise, adapted from Graff and Birkenstein’s templates for academic “moves” developed in They Say / I Say, helps students clearly interweave their own voices and the voices of the narrators as they report their finding and develop their arguments. Rather than presenting students with ready-made templates, we ask students to construct templates based on course readings about literacy narratives. For example, we have used passages from Cynthia Selfe and Gail Hawisher’s Literate Lives in the Information Age: Narratives of Literacy from the United States (2004) and Deborah Brandt’s Literacy in American Lives (2001) to illustrate how students might present a case study of a single literacy narrative and discuss a theme that weaves across multiple narratives.

For instance, turning to the theme of “The Prestige of Reading,” Brandt writes, “Three quarters of the people I spoke with said that reading and books were actively endorsed in their households” (2001, p. 150). From that example, students might generate the following template for qualifying a quantitative claim, “X of the X narrators (said, recalled, argued) that ______ .” Introducing the narrative arc mentioned above, Ahmed, Faine, and Yurkowski emphasize its presence in all of the five narratives they discuss: “They all attribute some of their skill to their childhood congregations or Sunday school classes, but again, it is not only the faithful elements of these narratives that make them cohesive. It is the application of their skills to a different cause” (“Introduction”). Introducing a supporting example from one narrative, Brandt writes, “For instance, Betty MacDuff, a retired journalist born in 1924, whose father’s education had ended in the third grade, recalled…” (p. 150). Consequently, students might construct the following template for providing key background information about narrators in parenthetical phrases and clauses: “X, an X, whose X, (recalled, mused) ______ .”

Passages in which Brandt and Selfe and Hawisher characterize what a narrator does rather than simply reporting what the narrator says might yield the following templates: “X recalled; X remembered; X explained, X (wept , beamed, smiled) recalling, X reported, X confided, X described, X concluded” and so on. In this instance, students might build on a set of speech acts that they had coded in their own analyses. Selfe and Hawisher (2004) also provide an example of acknowledging the role of an interviewer in a literacy narrative: “When asked about her family circumstances, Karen replied…” (p. 76). From that example, students might construct templates such as “When asked X, Y replied _____” and “In response to a question about X, Y exclaimed _____ .” Perhaps more important than any stylistic help such work might provide, analyzing writing about literacy narratives and building templates of rhetorical “moves” in this way may remind students that they can attend to and discuss aspects of literacy narratives such as demographics, speech acts, pragmatics, affect, and non-verbal communication (for example, the common vocabulary of Black Church members, the pacing and emphasis of Black spoken-word poets, the references of Black LBGT citizens).

Black Narratives Matter: Reciprocal Benefits

As noted above, to succeed as the focus of a service-learning course, the Literacy Narratives of Black Columbus oral history project strives to provide students with a rich learning environment while simultaneously advancing partner communities’ goals. Students, perhaps, focused most immediately on work associated with two of three approaches to oral history described by Howard Sacks (2009). A documentary approach (p. 8)—which asks “What is this?”—characterizes students’ recognition of diverse literacy practices across individual life experiences and various cultural contexts. An interpretive approach (p. 11)—which asks, “Why does this matter?”—characterizes students’ linking the details of individual literacy narratives with broader concepts in literacy studies such as literacy learning, sponsorship, community literacy, the politics of “standard” literacy models, and diverse modes of literacy. Students also engaged with Sacks’s third approach to oral history—a civic approach that promotes civic goals and addresses social problems (p. 13)—especially through their interactions with individual narrators and community liaisons, for all of whom the documentation and celebration of Black literacy in worship, the arts, political activism, and community advocacy was personally and immediately important.

Moreover, students working as field-researchers, archival researchers, and writers explored not only the informational content of the archive but also its “rhetorical and technological nature” (Purdy, 2011, p. 44). For instance, in one of the LNBC courses focused on literacy in the Black Church, a community liaison and contributor noted that some members of his congregation did not have easy access to the DALN online and asked us to create a DVD of narratives that he could present at the church (Appendix C reflects the contents of that DVD online, though the DVD contained full versions of the narratives rather than links to the online versions). Complementing the Black History of Columbus project, the Literacy Narratives of Black Columbus provided the community with a collection of diverse literacy narratives composed by “author-users” (Purdy, 2011) and preserved in a trusted online archive for current and future community members, literacy educators and researchers, and the general public.

References

Atkinson, P., & Delamont, S. (2006). Rescuing narrative from qualitative research. Narrative Inquiry, 16(1), 164–172.

Bamberg, M. (1997). Positioning between structure and performance. Journal of Narrative and Life History, 7, 335-342.

Bamberg, M. (2005). Narrative discourse and identities. In J. Meister, T. Kindt, & W. Schernus (Eds.), Narratology beyond Literary Criticism: Mediality, Disciplinarity (pp. 213–238). Berlin, New York: de Gruyter.

Bertaux, D. (1981). Biography and society: The life history approach. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Bertaux, D. & Thompson, P. (1993). Between generations: The life history approach. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Bertaux, D. & Thompson, P. (1997). Pathways to social class: A qualitative approach to social mobility. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Borgatti, S. (n.d.). Introduction to grounded theory. Retrieved from http://www.analytictech.com/mb870/introtogt.htm

Brandt, D. (2001). Literacy in American lives. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brodkey, L. (1987). Writing ethnographic narratives. Written Communication, 4(1), 25-50.

Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1-21.

Bruner, J. (1994). The remembered self. In U. Neisser & R. Fivush (Eds.), The remembering self: Construction and agency in self narrative (pp. 41-54). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bruner, J. (2001). Self-making and world-making. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 25(1), 67-78.

Bucholtz, M., and Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: A Sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies, 7, 585–614.

Carter, S., & Conrad, J. H. (2012). In possession of community: Toward a more sustainable local. College Composition and Communication, 64(1), 82–106.

Clifton, J., Long, E., & Roen, D. (2013). Accessing private knowledge for public conversations: Attending to shared, yet-to-be-public concerns in the Deaf and hard-of-hearing DALN interviews. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.) Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Commission on National and Community Service. (1993). What you can do for your country. Washington, DC.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Corkery, C. (2004). Narrative and personal literacy:

Developing a pedagogy of confidence building for the writing

classroom. (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Maryland.

Retrieved from https://drum.lib.umd.edu/bitstream/handle/

Daya, S. & Lau, L. (2007). Power and narrative. Narrative Inquiry, 17(1), 1-11.

DeBlasio, D. M. (2009). Catching stories: A practical guide to oral history. Athens, Ohio: Swallow Press.

DeRosa, S. (2002). Literacy narratives as genres of possibility: Students’ voices, reflective writing, and rhetorical awareness.” Ethos.

Eldred, J. C. & Mortensen, P. (1992). Reading literacy narratives. College English, 54(5), 512-539.

Earle, W. (1972). Autobiographical consciousness. Chicago: Quadrangle.

Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 5(4), 327-58.

Gaillet, L. L. (2012). (Per)Forming archival research methodologies. College Composition and Communication, 64(1), 35–58.

Georgakopoulou, A. (2006). Thinking big with small stories in narrative and identity analysis. Narrative Inquiry, 16(1), 122–130.

Gergen, K. & Gergen, M. (1988). Narratives and the self (vol. 21). In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology: Social psychological studies of the self, (pp. 17-63). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Graff, G. & Birkenstein, C. (2014). They say / I say: The moves that matter in academic writing (3rd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Hesse-Biber, S. N., & Leavy, P. (Eds.) (2008). Handbook of emergent methods. New York: Guilford Press.

Higgins, L., Long, E., & Flower, L. (2006). Community literacy: A rhetorical model for personal and public inquiry. Community Literacy Journal, 1(1), 9-42.

Kraft, R. J. (1996). Service learning: An introduction to its theory, practice, and effects. Education and urban society, 28(2), 131-59.

Krauss, W. (2006). The narrative negotiation of identity and belonging. Narrative Inquiry, 16(1), 103–111.

Kreiswirth, M. (2000). Merely telling stories? Narrative and knowledge in the human sciences. Poetics Today, 21(2), 293–318.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1998). Just what is critical race theory and what’s it doing in a nice field like education? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11(1), 7-24.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2005). The evolving role of critical race theory in educational scholarship. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 115-119.

Ladson-Billings, G. & Tate, W. (1995). Toward a critical race theory of education. Teachers College Record, 97(1), 47-68.

Langellier, K. M. (1989). Personal narratives: Perspectives on theory and research. Text and Performance Quarterly, 9, 243-276.

Langellier, K. M., & Peterson, E. E. (2004). Storytelling in daily life: Performing narrative. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Lapadat, J. C. (2004). Autobiographical memories of early language and literacy development. Narrative Inquiry, 14(1), 113–140.

Long, E. (2008). Community literacy and the rhetoric of local publics. West Lafayette: Parlor Press.

Lummis, T. (1987). Listening to history: The authenticity of oral evidence. London: Hutchinson.

Matthieu, P. (2005). Tactics of hope: The public turn in English composition. Boynton-Cook.

McCarthy, S. (2012). Relational reinvention: Writing, engagement, and mapping as wicked response. (Unpublished dissertation). The University of Texas at Austin.

McKee, H. A. & Porter, J. E. (2012). The ethics of archival research. College Composition and Communication, 64(1), 59–81.

Olson, G. A. (2002). Rhetoric and composition as intellectual work. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Parks, S. & Goldblatt, E. (2000). Writing beyond the curriculum: Fostering new collaborations in literacy. College English, 62(5), 584-606

Phelan, J. (2013). Afterword: A matter of emPHASis: Literacy narratives and Literacy narratives. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Phelan, J. & Rabinowitz, P. J. (2005). Narrative judgments and the rhetorical theory of narrative: Ian McEwan’s Atonement. In J. Phelan & P. J. Rabinowitz (Eds.), A Companion to Narrative Theory (pp. 322-36). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Purdy, J. P. (2011). Three gifts of digital archives. Journal of Literacy and Technology, 12(3), 24–49.

Sacks, H. (2009). Why do oral history? In D. M. DeBlasio (Ed.), Catching stories: A practical guide to oral history. Athens, Ohio: Swallow Press.

Selfe, C. L. & Hawisher, G. E. (2004). Literate lives in the information age: Narratives of literacy from the United States. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Sigmon, R. (1979). Service-learning: Three principles. Synergist, 8(10), 9–11

Thompson, P. R. (1988). The voice of the past: Oral history. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, P. R. (1990). I don’t feel old: The experience of later life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ulman, H. L. (2013). Reading the DALN database: Narrative, metadata, and interpretation. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Wells, S. (2002). Claiming the archive for rhetoric and composition. In G. Tate (Ed.), Rhetoric and composition as intellectual work (pp. 55-64). Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Zdenek, S. (2011). Which sounds are significant? Towards a rhetoric of closed captioning. Disability Studies Quarterly, 31(3). Retrieved from http://www.dsq-sds.org/article/view/1667/1604