Teaching Refugee Students with the DALN

MARY HELEN O’CONNOR

ABSTRACT

This chapter describes an experience teaching digital storytelling to refugee students in a traditional college composition course. Using the DALN as a resource for primary research into the literacy practices of refugees and immigrants, students learn to critique the politics and power dynamics of language and literacy. Drawing on teaching practices of modern compositionists (Hawisher, Selfe, Norcia, Shipka, Ball, Wysocki, Hocks), this chapter will chronicle how a digital archive, digital tools, and a digital assignment offer students in my composition class a constructivist approach to learning how to communicate effectively in both print and digital spaces. Teaching digital and multimodal composition challenges traditional academic practices limiting student communication to print assignments. For students new to English, multimodal composition offers new methods for constructing meaning. This is especially important for refugee students for whom these pedagogies offer more a powerful way to control representations of themselves. The DALN also creates a space where refugee students are able to publicly share self-authored narratives of identity and experience—a public space for refugees to reclaim power. This work draws on what scholars of New Literacy Studies and, more recently, scholars of community and everyday literacy have revealed about students from marginalized groups and backgrounds. This chapter attempts to provide fellow compositionists who have access to refugee and immigration student populations insight into how alternative modes of composing (i.e., multimodal composition) can increase student agency, self-efficacy, and overall literacy, as well as provide sample assignments and best practices for those seeking to adopt these pedagogical tools in their own classes.

***

Multimodal Composition and Refugee Students

But we also tell stories as a way of transforming our sense of who we are, recovering a sense of ourselves as actors and agents in the face of experiences that make us feel insignificant, unrecognized, or powerless. This covers the connection between storytelling and freedom—the way we recapture, through telling stories, a sense of being acting subjects in a world that often reduces us to the status of mere objects, acted upon by others or moved by forces beyond our control. —Michael Jackson (2002, p. 17)

English teachers have struggled to adapt instructional methods to keep pace with the impact of technology on communication. Whether teaching writing in digital environments, composing and publishing in public digital spaces, or teaching research in the age on the internet, we frequently look to disciplinary organizations and scholars to inform our work in the classroom. The NCTE (2005) Position Statement on Multimodal Literacies offers justification for why and how multimodal composition should be included in the composition classroom. In these guidelines, specific attention is called to providing “the necessary support and infrastructural, cultural and technological adjustments, including access to technology for people with diverse abilities and needs.” Refugee students constitute a group for whom we need to provide particular support. As teachers, we must move away from the deficit perspective of ELL students and toward an acknowledgement of the rhetorical practices of multilingual, multicultural students. Composition scholars contend, “Multimodal digital composing practices offer alternative methods of teaching, learning, production, and assessment that the potential to disrupt traditional banking system of education” (Avila & Zacher Pandya, 2012, p. 6)—the reductive, test-centered system to which most newcomer and immigrant children are exposed (Collins & Halverson, 2009). My experience teaching multimodal composition to refugee students can offer teachers models for working with students from a wide range of backgrounds and literacies, with the added bonus of engaging native-born, monolingual students in conversations with students they might otherwise never know. By learning to communicate in this multicultural, multilingual community, students “learn to orchestrate competing voices” (Pandya, Pagdilao, & Kim, 2015, p. 2).

For refugees, learning to construct their own representation and tell their own story with tools of the dominant discourses of power disrupts the political hegemony silencing refugee voices that might challenge the “international order of things” (Sigona, 2016, p. 372). As political objects in the international world order/international humanitarian regime, refugees naturally must construct narratives and stories of violence, exile, oppression, and victimization to survive. Teaching refugees to recognize and value their own literacy practices, cultural values, and memories transgresses the prevailing “feminized and infantilized images of ‘pure’ victimhood and vulnerability” produced and reproduced in an endless stream of refugee representation in all forms of discourse—mass media, academic, and humanitarian (Sigona, 2016, p. 370). Alongside the mission of teaching refugees self-representation and communication skills is bringing these narratives and identities into public discourse. The archive, as a repository of public memory, permits refugees to act as researchers, scholars, and citizens as “they gain both the agency and the subjectivity to rethink history and their own relationship to it” (Norcia, 2008, p. 95). The contribution of my refugee students’ literacy narratives to the DALN creates a history in many cases where there are no archives at all. Refugees arrive in the U.S. with the clothes on their back, having abandoned their homes, schools, and communities—most often without diplomas, passports, birth certificates, or photographs. The DALN offers a space for refugee students who have crossed many borders, speak multiple languages, and share many cultures to create their own history (Hawisher, Selfe, Kisa, & Ahmed, 2010).

Composition teachers must consider “how meanings are made, distributed, received, interpreted and remade… through many representational and communicative modes—not just through language.” —Gunther Kress and Carey Jewitt (2003, p. 1)

Introduction

When someone has lost everything, family, home, land, faith, and even their identity, the only thing left that no one can take away is their story. —Hser Ku Moo

It is 10 a.m. in my English 1102 composition class and students are presenting the culmination of about a month of researching, indexing, composing, recording, and editing their video literacy narratives. I ask for a volunteer to go first. To my surprise, a shy young woman who has hardly spoken all semester approaches the podium. She clicks the link to her project and the room fills with her delicate voice, “Hello my dear fellow classmates. My name is Hser Ku Moo.” The screen brightens with a still photo of her smiling, head tilted slightly, wearing a tasseled hat traditionally worn by the Karen people of Burma. In the next frames, we visit the refugee camp where she was born and grew up. We witness her struggles to learn to read and write and speak in both her native language and in English. Her literacy narrative takes us from one side of the globe where a government is driving ethnic groups from their homeland to the classroom where we are sitting watching this unfold on the screen in front of us. By the end of the video, tears fill my eyes and the class erupts in clapping and compliments. In two short minutes, Hser reveals herself to all of us. She tells us her story in her own words and in her own way beginning with the declaration, “When someone has lost everything, family, home, land, faith, and even their identity, the only thing left that no one can take away is their story.”

I have shared Hser’s video literacy narrative with other students and faculty in classes, workshops, and conferences. Invariably, it results in tears from audience members. When I reflect on why her work is so compelling, I believe it successfully demonstrates some of what works well in the composition classroom with refugee students. This pedagogical approach increases the ability of my refugee students to communicate through the use of digital tools. This gives them more control of their own story as they are not limited only by written English language proficiency. It gives them agency in an environment where they typically experience very little. My students tell me these assignments boost their confidence. They offer a way to celebrate the competencies they possess that are generally ignored, overlooked, or unacknowledged in the traditional college classroom.

Globalization is changing the composition of a writing classroom in the United States, which should in turn inform and influence teaching. Technology is also constantly shaping the content and delivery methods of what is offered to students in a composition classroom. I have found multimodal composition a promising strategy for teaching refugee students. As our culture and classrooms become transnational, approaches to composition beyond the bounds of the historically print modes of writing instruction offer a way to acknowledge literacy practices and knowledge historically overlooked by a teaching tradition rooted in western rhetorical concepts of literacy. Teaching digital composition with my refugee students resists the deficit model of writing instruction dominating western classrooms “in which ‘non-Western’ cultures are seen as lacking rhetorical concepts or rhetorical tradition” (Hesford & Schell, 2008, p. 465).

Although we are almost two decades into the new century, instructors are still grappling with teaching approaches beyond the scope of print literacy. For a transnational student, learning a new language and often an entirely new alphabet limits their ability to learn and to communicate. Multimodal composition offers a transnational student additional tools and methods of communication beyond print or alphabetic literacy to more accurately represent their own reality, their own experience, their own identity—“[y]et in the twenty-first century many of us cling to the familiar educational tools of the immediate past and continue to teach the rhetorical means to manipulate limited alphabetic representations of reality” (Hawisher et al., 2010, p. 57). I believe this is a concern not just for refugee students but for all students as new generations of school-age children in U.S. schools are increasingly learning in largely digital environments.

In addition to expanding the communicative ability of my students, this work connects my students with the world beyond the door of the classroom and the borders of their state and nation. My teaching is also closely bound to civic engagement, responsibility, and action, so as the confluence of technology and globalization bring cultures into closer contact this type of instruction becomes a valuable way to teach intercultural communication and global citizenship. Hser’s video (as well as those of my other refugee students) situates her personhood and her experience in relation to the global politics shaping the ideology of students in our classrooms. Wendy Hesford (2006) notes, “As we think through the meaning of the global turn for rhetoric and composition studies, we must bear in mind that mobility is not an option for many groups and populations and has in fact been forced upon others” (p. 790). Refugees are among the most marginalized groups in the world. Hser’s narrative encourages my students to question the formidable forces of power and privilege oppressing more than 65 million individuals on the face of our planet.

The Global Refugee Situation

The refugee problem is a foreshadowing of the 21st century’s great migration. —Michel Foucault (1979)

In 2015, the world was captivated by a photograph of the body of a 3 year-old Syrian boy washed up on the shores of a Moroccan beach. The Syrian refugee crisis has awakened many in the United States and elsewhere to the reality that millions of people across the globe are refugees who have either fled their countries in fear of persecution or been internally displaced by conflict in their home countries. And while the image of the body of this small child is haunting, in reality, it hardly depicts the massive scale of the migrant crisis across the globe. Current statistics from the UNHCR report disturbing trends for displaced people across the globe. More than 65 million people ended the year as “forcibly displaced” in 2015—the most in recorded history (UNHCR). The term “refugee” is defined for legal purposes by the UN as a status of personhood which marks an individual as eligible for humanitarian aid and protection on the global stage. The United Nations’ 1951 Refugee Convention defines a refugee as follows:

Owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence, is unable, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

Amnesty International estimates at least 3,500 people died in 2014 making the same crossing of the Mediterranean Sea as the Syrian child. Thousands die every year trying to make their way from Central America across Mexico, piggybacking on freight trains, walking and swimming rivers, paying smugglers their life savings, dodging gangs and government officials to get to United States. Millions more languish in refugee camps for years. More than half (51%) of refugees are women and children. According to the U.S. Department of State, the United States has resettled more refugees than all other developed nations worldwide combined, yet less than 1% of refugees worldwide will ever have the chance to start their lives over in new country. Those who do make it to a new country face steep cultural divides, ethnic and racial discrimination, economic hardship, and the myriad of problems that come with learning a new language, a new culture, and often a completely new way of life. For most refugees, this adjustment takes place in schools.

The vast majority of refugees arriving in the United States are resettled in thirteen locations, including Clarkston, Georgia, where I teach English at a community college. With 40,000 refugees resettled here since 1983, our community has struggled to identify and meet the specific needs of this population. Schools bear the burden of providing the adaptive skills refugees needs post-migration, because their ability to navigate a new culture often depends on their ability to read, write, and speak the primary language in their new home country. Functional literacy also contributes to their ability to participate in public discourse—go to school, become a citizen, work. Issues of literacy become the focus of a refugee’s life post-migration. Educational institutions of their host nations become the primary site of learning and acculturation for refugees. Here their abilities and identities become shaped by the categories into which they are sorted: ESL, ELL, literate, illiterate, preliterate. While much has been done to identify and meet the needs of ELL students in the United States, very little has been written or published addressing the discrete needs of refugee students in American classrooms. This chapter aims to remedy this gap in academic studies by answering the call from researchers for more work to be done in the fields of community literacy, literacy studies, and education for refugee students (McBrien, 2013; McDonald, 2013b).

In order to understand how new methodologies of teaching informed by “feminist research, new literacy studies, critical theory, and digital media studies” (Hawisher et al., 2010, p. 56) impact my students, I want to examine their literacy narratives to understand their definitions, perceptions, and interpretations of language, literacy, and power. The DALN offers a rich collection of multilingual and multimodal stories that legitimize multicultural and multilingual literacy skills, practices, and experiences for refugee students. Investigating the archive helps refugee students consider the ways literacy is defined, practiced, and valued in other cultures. With this new perspective, refugee students find the courage and confidence to tell their own stories. Refugee literacy narratives reveal how literacy can be used to control and marginalize groups of people—whether it is the deficit or monolingual model of literacy practiced in U.S. classrooms or the use of a language to spread ethnocentric political aims in a civil conflict. Their narratives bear witness to how literacy is used to separate and marginalize as well as ally and organize. Power emerges as a unifying theme to many of the stories told by refugees, and this power is most frequently associated with English language proficiency. As curators of the DALN exhibit “Multilingual Literacy Landscapes” also found, “An important commonality amongst our students’ narratives is the fact that each is a reference to the student’s acquisition of English” (Frost & Malley, 2013). English proficiency looms large in the lives of multilingual and especially refugee students. Though my intention is to help them appreciate the literacy skills and experiences they possess besides English proficiency, the stories they tell demonstrate that English language proficiency is the key to their resettlement in the United States.

When teaching refugee students composition, I strive to provide them with the tools to construct their own descriptions and definitions of their stories, lives, and experiences. This process boosts their confidence and changes their attitudes and beliefs about their own competencies with language and schooling. I have developed a series of assignments designed to empower my refugee students to speak back to those dominant discourses defining them as illiterate or voiceless. This work recognizes and elevates types of literacy discounted or downplayed in the traditional college composition classroom. My job teaching literacy narratives, as David Bloome (2013) suggests in “Five Ways to Read A Curated Archive of Digital Literacy Narrative” is to “reposition the tellers of literacy narratives from the social and educational margins to the center.” When refugee stories become visible and powerful using dominant discourse tools, refugee students become “experts in their own literacy development and agents in future learning” (Comer & Harker, 2015, p. 66). The DALN exists in the intersections of narrative, digital, multimodal, and archival, a place where refugee students can become more aware and in control of their representation in a transnational world and more competent in negotiating the the competing voices of nationalism, multiculturalism, and increasingly xenophobia and oppression. As Comer and Harker (2015) assert, “The pedagogy of the DALN taps into and asks students to negotiate these powerful forces.” The literacy narratives presented here demonstrate how well, and with what benefits, refugee students respond to this challenge.

The Assignment Design and Process

In my opinion, a video project is harder than a research project. —Abuukar Abuukar

I begin the study of literacy with students through a discussion of what it means to be literate. Most sections of my courses have a large number of non-native students. During the semester described in this chapter, our class had students from Iraq, Burma, Somalia, Nepal, Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Vietnam, Bhutan, and Eritrea. All of these students have taken language placement exams and ESL classes before landing in my composition courses. The native-born students have also taken tests that name, label, and define their literacy skills and knowledge. On some level, every student has formed their own idea about what it means to be literate. For the majority of my students, this means they have been classified as “less” literate than their classroom peers at some point in their schooling. Almost all of my students have had to pass multiple “learning support” or ESL English classes before they can be placed in this composition class. When I ask them what it means to be literate, naturally, their response always has something to do with the ability to read and write in English. As student Ali writes, “My initial perception of the term (literacy) was being able to speak and write in English.” Edwin relates a story from his schooling, “Every English teacher asks, at the beginning of each year, what is literacy. And year after the year the response is the same answer. The ability to read and write.” I help them critique this definition by asking them if they are literate in other languages or skills like music or computer programming. We create lists of all of the literacy skills practiced by members of our class. I ask students questions crafted carefully for those who may have never been through traditional K-12 schooling like most U.S. born students:

- How did you learn to read and write?

- Who taught you about letters, numbers, or words?

- Who taught you to read?

- Where did you learn to read and write?

- How many languages do you speak/read/write?

- Did you attend school when you were very young?

- When did you first attend school?

- Do you have happy or sad memories about school? Or learning to read and write?

- When did you first attend school in the United States?

- Did you have books at home or at school?

- When did you first see a television?

- Where did you first use a computer?

- Have you had especially helpful teachers?

- How did you feel in school when you first arrived in the U.S.?

These questions help launch an exploration of the differences between education, schooling, and literacy. For many of my refugee students, this is the first time anyone has acknowledged their multiple literacies. Refugees are rarely bilingual. Crossing multiple borders and boundaries to land in the U.S. requires basic fluency in multiples languages, yet all that seems to count for them in the United States is speaking, reading, and writing in English. Most speak three or more languages and often read and write in multiple languages.

|

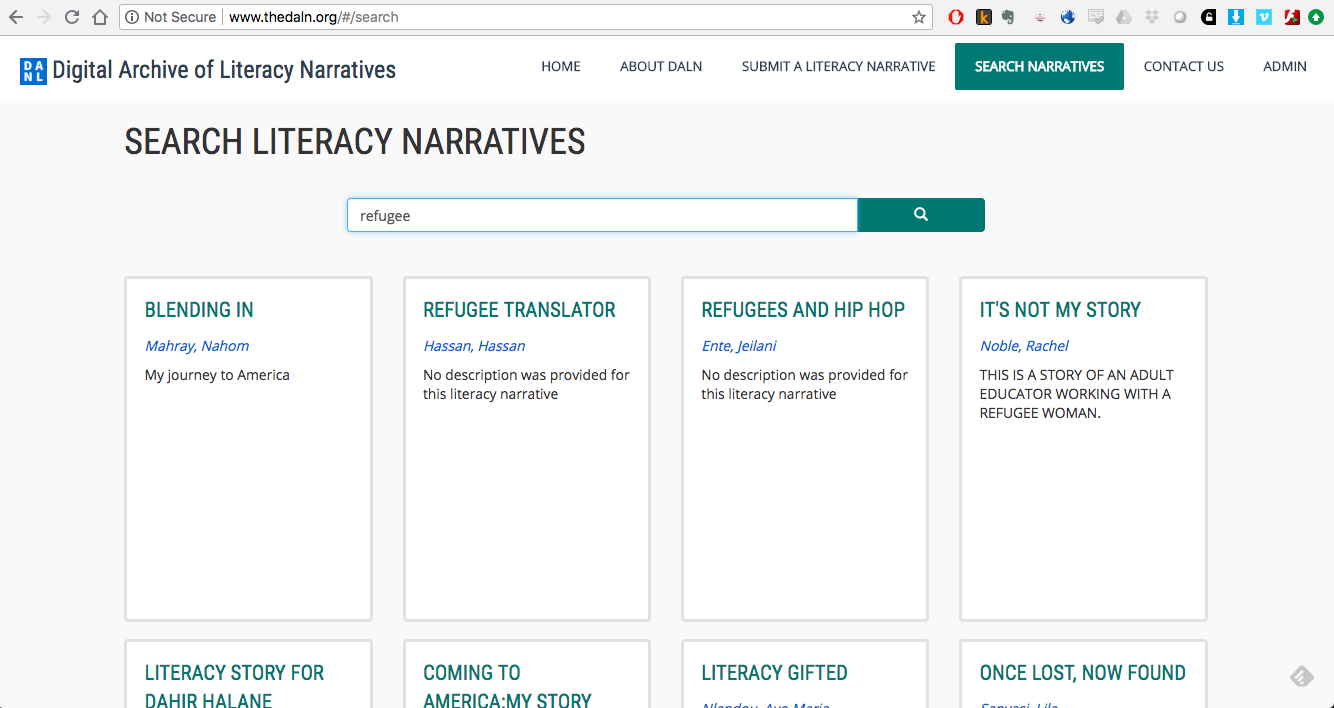

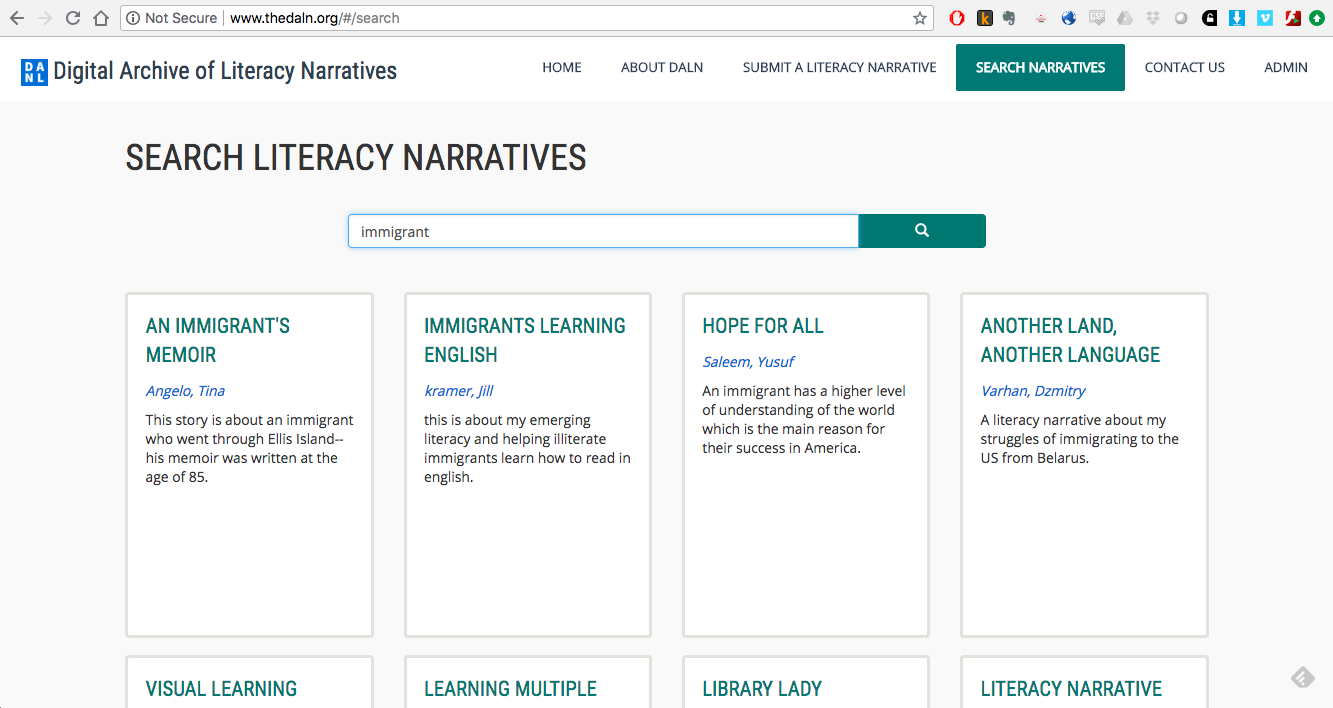

At this point in our class discussion, I introduce the students to the DALN. I will use a word suggested by the class to search the archive and locate narratives to show the class. We search terms like refugee, Spanish, illiterate, Afghan, Somali, and ELL. Once we have explored the archive together as a class, their homework asks them to produce a short annotated bibliography of narratives that specifically interest them or might be relevant to their own literacy experiences in some way. This gives them practice searching and locating pertinent artifacts. After the students submit their annotations, the class meets during one class session in a computer lab, where students are trained to use the iPads issued for the semester through iTeach, a college-wide technology enhancement grant program. An instructional technologist teaches the basics of the iPad, from setting up an iCloud account to basic videography skills. Students learn how to compose shots and capture quality audio. The trainer also covers searching the Internet for images, saving media, cropping and scaling images, basic copyright rules, and transferring files among the iPad, desktop machines, and the Internet. In a community college population like ours, this is a powerful program. Though most of our students have access to mobile technology, large numbers still do not own laptops or tablets.

While we are focusing on technology training during face-to-face class meetings, I ask students to begin drafting their written literacy narrative for homework. This assignment, “My Literacy Narrative” (see Appendix A), is presented as a formal narrative essay. I encourage students to use their best storytelling tools and techniques in a written composition about some aspect of their encounters with literacy practices and activities. They have wide latitude to define literacy based on their own interpretation of the term. During our next class meeting, I ask the students to partner up and pull out their iPads. Without specific instructions, I tell them we will be practicing their new video recording skills by interviewing one another about their “literacy experiences.” I briefly review the highlights of our previous class discussion about literacy and literacy experiences and send them to find a quiet spot on campus to conduct the interviews. When the students return, I ask them to share their recorded interviews in small groups and come up with a list of “what worked well” and “what did not work well” during the exercise. When we come back together as a class and share these lists, the students will inevitably share many technical difficulties including trouble with background noises, finding a quiet spot to record, interviewees who speak too softly, missing the record button, and holding the ipad still. The most notable difficulty they will report is the feeling of unpreparedness after they begin the interview. Most students will fumble around searching for questions to ask because they haven’t thoughtfully planned their interviews. They remember this discomfort so that their next attempts at recording will include more planning and preparation. I believe students are so immersed in our media culture they take it for granted that a quality video interview is not as easy as pulling out their phone and recording the Snapchat and YouTube videos they crank out every day. This exercise has been particularly effective in my classes over the years. Later in the semester when we are producing more complicated technology projects, very few of them will forgo the planning stages of a project and just dive right in.

I also try to include as many opportunities for verbal communication, sharing, and presentation in both small groups and to the class as a whole as possible throughout the semester. This affords my refugee students more opportunities to practice speaking English in a supportive environment. Meeting new friends is often difficult for college students, even more so for ELL and refugee students. However, nudging refugee students into classroom working relationships with other students has proven to be one of the most helpful outcomes of our classroom activities. I intentionally organize groups based on nationality and discourage students who speak the same language from partnering. A typical small group in my class will include members from four or more continents with language skills ranging from Dhongzu and Russian to Ewe and Arabic. After the interviewing practice, students are ready to practice their new skills. For homework, I formally assign “The Literacy Narrative Video Interview” (see Appendix B). This assignment asks students to apply what we have learned in the iPad training class and in-class interviewing experience. It also requires some written analysis of the recording. Using their new interviewing skills and technology tools, students must collect an interview with a member of their community about their experiences with literacy. This type of ethnographic assignment offers an opportunity for students to play the role of the interviewer. They must learn to construct an interview to elicit the information they would like to gather. Students report finding this much more difficult than they initially expected. They run into problems with both their interview subjects and technology. Interview subjects can be uncooperative, shy, or too quiet. Audio recordings can be too soft, cameras wiggle too much, and batteries run out at the most inconvenient moments. Solving these quandaries is an important learning experience for the success of future multimedia assignments.

The final component of our unit comes at the end of this work when I instruct the class to compose a video version of their literacy narratives. By this time, I have returned the graded version of their written narratives with my feedback, suggestions, and assessment. I ask students to consider how they can enhance their narrative by using images, sounds, and digital effects to tell some aspect of their story. I explain it is not necessary to tell the entire written narrative and also give them option of sharing someone else’s literacy experiences. Premiering the literacy narratives in class pressures students to perform for their peers, so most of them will invest more time and energy into the project than they typically do on a traditional composition assignment. I have experimented with various assessment scenarios including collecting rubric feedback from the class and combining it with my own for a final grade (see Appendix D). In addition to the rubric, students reflect on our series of literacy assignments on their final exams. In a keyword essay format, they must define terms including literacy, school, and education, and discuss their attitudes and beliefs about these concepts both before and after we have studied them. I also ask them to compare the process of creating their video and composing their written literacy narrative. Students who feel compelled to share their narratives are encouraged to submit them to the DALN at the end of the semester. The paperwork and instructions for submitting them using a desktop computer are included on the final exam. Here is what they have taught me about the work we do, through four major themes common in the work produced by my students.

Literacy, Power, and Language

Language is the backbone of literacy. —Indra Subedi

Throughout both their video narratives and written reflections,

refugee students frequently equate language literacy with power.

Priscilla writes:

I think literacy, as I learned in class, is power because without knowing a language people feel powerless. Being literate does not necessarily mean that a person finishes school and gets a degree. It can just be simply knowing a language and speaking it. Everyone has their own language so no one is really illiterate. Before taking this class I have never thought about what literacy is, but after I am glad to have learned it because literacy affects everyone’s life.

Whether considering schooled literacy or the literacy practices of everyday life, refugee literacy narratives often stress the power dynamics involved in their lives crossing borders, cultures, and languages. Ali tells a story in his video narrative about the power of language to control and contain. He compares his experience as a proficient English speaker with the experiences of other Somalis who are forced to rely on interpreters with airport officials, school officials, and “white people”: “From then on I no longer needed anybody translating for me, because when somebody’s translating for you, I feel like they control you instead of you controlling them. That would be like a power struggle.” With the ability to speak English he continues, “Wherever I am I will be able to express (myself) without needing anybody translating for me.” Refugee literacy narratives frequently focus on the power dynamics of language proficiency. Dawt shares similar feelings about English and his experiences in school exclaiming, “I felt powerless.” Lost in a new school and new culture and new way of life, he cannot locate his classrooms or navigate the lunchroom. He couldn’t figure out how to get food for lunch and was afraid to ask anyone for help. Schools are critical sites of struggle and adaptation in these narratives, confirming what research tells us about the role of schools as the primary site of cultural learning and assimilation for refugee students (McBrien, 2013; Pipher, 2002). Dawt, Mohamud, Abuukar, Ali, Edwin, and Nahom all focus on school experiences in their narratives. In his video, Abuukar makes a connection between literacy and schooling and success: “As I said before, I will show you how he became successful.” For Ali, his English proficiency surprised the teachers and staff at the high school where he first registered upon arriving in the U.S. Having this ability, he says, “improved my life.” Dawt, Edwin, Mohamud, and Nahom share their feelings of isolation and difficulty coping at school. When Nahom ultimately finds success at school by learning enough English, he exclaims in his video narrative, “With my new-found knowledge, I was no longer powerless.”

Confidence Speaking and Writing

The students’ literacy narrative stories I learned in class give me more courage in my life. —Mansour Fofana

The process of composing literacy narratives while learning new technology boosts the confidence of refugee students as speakers, readers, writers, and digital compositionists. Nahom writes, “My writing has improved because I started noticing my mistakes. I learned so much stuff from this class, but the best part was I learned not to be nervous while speaking in front of class.” Working alongside their classmates, refugee students are compelled to practice their speaking and writing in ways that are absent in a lecture-based course. Many refugee students admit they are often afraid to participate in group discussions or speaking out loud in the classes. Both Yanuka and Nahom felt emboldened by course work. Yanuka writes:

Working in a group and getting to know friends from different countries was fun and also it increased my confidence. Now I can talk in front of massive groups of people. The best part of taking this class is, whatever we had to do, we had time to work in class. That way we were able to ask anything whenever we didn’t understand an assignment.

Nahom echoes her sentiment:

I learned a lot of things from this class. I learned to build enough courage to talk in class. I was exposed to a very diverse group of people. Listening to my diverse classmates stories about literacy helped me learn the struggles in their life. My confidence level boosted sky high because of the diversity of the class. I feel comfortable talking to an individual that had similar challenges in learning the new language.

Nahom was a very shy middle-schooler when I first met him in a summer literacy program for ELL students. His written literacy narrative describes his isolation and loneliness as a small child moving to 3 countries in the span of one year as his family searched for a safe haven. Most of his childhood was spent living in countries where he was unable to speak the dominant language. When he finally arrived in the U.S., he described himself as “introverted” and “and better off by myself most of the time.” He hardly spoke a complete sentence in class during the years I knew him before he came to college. Things have certainly changed. Nahom discovered his confidence and now actively participates in his classes. He contributes his opinions and has recounted the details of his literacy story for both students and faculty in presentations, at an international student day, and in other classes. He has taken three more of my classes since the first composition course, and each semester he brings along a new cohort of friends. I can rely on him to speak up and participate in class discussions. He led the development of a complicated documentary video project in my world literature class. His overall engagement and performance as a student has steadily intensified since he first shared his literacy narrative as a freshman in my composition course. He is not alone. Mansour echoes Nahom and Yanuka’s enthusiasm, “Since I learned different strategies and new terms in class, I believe that my confidence increased for my next English class. It also increased the first day I knew that I had friends, and a good teacher in class who could help me out if I needed it.”

Other corollary learning outcomes for the DALN assignments are the critical thinking and new literacy skills required for translating a written narrative to video. The changing demands of our modern world require new types of literacy from students, and many of my students have limited access to the types of digital tools used for composing multimedia projects. Technological literacy has also become a requisite component of the composition classroom. The use of “digital technologies… facilitate and demand new and more processual and social modes of shaping, sharing and storing knowledge, and because that knowledge production plays out in often-hybrid online and offline spaces” (Drotner, 2013, p. 39). For refugee students, using digital tools to tell stories in the English classroom expands their communicative abilities. Instead of solely relying on their limited English language proficiency to communicate their stories, they can use images and sound. Hser’s video narrative shows heart-wrenching images of the refugee camp where she was born and grew up, sinister-looking Burmese soldiers, a graphic of her native alphabet, and map locating her homeland in relation to the U.S. Mansour’s and Ave Maria’s narratives brim with vivacious music and colorful images of their West African homelands. Nahom, Hser, and Abukaar employ maps to give the audience perspective on the great distances they have traveled to arrive in the U.S. Technology provides a way to share rich cultural artifacts like music and dance in a way that is not possible in an essay written by a student who has just started to learn English.

My refugee students often admit a significant amount of fear and uncertainty about these types of technology projects. Many are new to the internet, computers, and technology in school. Hser acknowledges how nervous she was when I first assigned the project, “Professor O’Connor, when you started mentioning the ‘video project’ everyone seemed happy except for me. I never had an experience composing a story and converting it to video.” Despite this hesitancy, students are generally pleased at the end of the process and surprised at the amount of work required for this type of assignment. Yanuka writes, “I learned many new things. I learned almost everything about editing a video, for example, putting the clips and pictures together, inserting transitions in between clips, adding titles, importing new music, adding text, saving video etc. The video project was fun.” When I speak to other faculty about using technology in the classroom in workshops or presentations, I still meet quite a lot of resistance and skepticism about the value of usefulness of these types of assignments. I like to bring students to faculty workshops and presentations so that they can provide the testimony to respond to these criticisms. Comments like this one from Abuukar are powerful: “In my opinion, a video project is harder than a research project. For example, I don’t like standing in front of a camera to record myself. It taught me that I can do it and it increased my confidence.” The vast majority of students report video projects require more work and significantly more time than a traditional written assignment. They also insist this type of work is connected to an improvement in their writing skills. This may be a change in attitude or a boost in confidence. Either way, for refugee students the impact is powerful. Ali points out, “Another thing I learned in this class was that writing five or six long pages of an essay was not the only way to express your thoughts or creativity. The professor gave us a literacy story and we had to do it in a video format. In the end most of us did fabulous work and the professor was amazed by our creativity.” Technology as an instructional approach can ignite interest in subject matter students find uninteresting. This may be especially true for students who have not had practice in the types of research and writing assignments common in American college classes. Indra writes, “I received technical support from this class, which I never had before. For instance, my professor provides us iPads with different websites, which enable us to prepare videos and to write research papers with new information. In the past, I am not interested in reading stories and poems, but now by taking this class I feel fully interested in reading and searching new information.” Students also find practical value in the assignments, as Anil notes:

This class taught me many life skills lesson which will help in my future. One important part that I learned is writing itself. As I look back, I found peace within me knowing that I can use these lessons to make life better. It means I improved my writing as compared to the beginning of the semester. In fact, whatever I learned in this class, all my credit goes to Ms. O’Connor. Without her contribution, I may not be able to survive.

As a college composition instructor, the focal point of my work is all too often how well I have taught students alphabetic fluency and print mastery. With administrative focus on assessments and testing, I frequently overlook the corollary learning outcomes. At the end of the semester, when I ask my students to reflect on the work we have done, I am gratified to see the impact of using the DALN as a pedagogical approach to teaching literacy, but the impact it has on my students cannot be measured by an assessment of their essay writing skills alone. The benefits exceed the bounds of the classroom.

Conclusion

Teachers should be aware of the ways multimodal, digital composition can help meet their immigrant students’ self-authoring needs and surpass the demands of the new standards (Common Core). Finally, to connect with others, to become more aware of one’s place(s) in an increasingly globalized world, and to orchestrate competing voices—these are the potential for multimodal, digital composition with immigrant youth to which we continue to aspire.—Jessica Zacher Pandya, Kathleah Consul Pagdilao, and Enok Aeloch Kim (2015, p. 2)

The literacy narratives and feedback of my refugee students demonstrate the potency of digital pedagogy in a traditional college composition course. Teaching multilingual, multicultural students to communicate with the tools of dominant discourses of power provides agency and self-representation to a population from whom these abilities have been eliminated. Refugee students learn to acknowledge literacies they possess beyond the monolingual, text-based tradition of the American college composition classroom in their exploration of the DALN and construction of their literacy narratives. This work empowers refugee students, validates their strengths, and encourages a more positive approach to literacy development.

Invariably, teaching with technology has its own hazards. Over the many years of using digital projects in my classes, I have learned a few hard lessons. The internal grant funding allowing my students to have an iPad for a semester is the luxury version of classroom technology, but this work can be done with basic technology. I have taught this project in an inner-city, under-funded middle school with ancient desktop Windows machines in a small library computer lab. School systems, colleges, and universities now offer software and software training to their faculty, staff, and students. Get familiar with your instructional technology colleagues and check out faculty development departments. Most students heading to college these days have been immersed in Google classroom or have already used a learning management system. Many students are shooting and editing video with their smartphones. Most know far more about technology than I ever will before they step foot in my classroom. This may not be true for my newly arrived refugee students nor my older non-traditional students. Pairing them with student who is comfortable navigating tech in the early portions of the assignment series prevents a lot of future frustration.

Another hazard involves technology infrastructure. Many schools limit bandwidth on popular websites like YouTube or use filtering software preventing access to some resources students use. One semester in the early years of teaching video stories, my students were excited and anxious to present their projects, but we could not play one successfully on the computer equipment in the classroom. Projects uploaded to YouTube would buffer endlessly, blip along for a few seconds, and stall out again. Even the videos uploaded to Dropbox were stalling out. A few students had loaded their assignments onto a jump (USB) drive and they played along beautifully. I integrated this critical lesson into future assignments by requiring students to submit their work to a web-based account as well as bring back-up “hard” copies of the projects on a USB drive for the final presentations. Plan ahead and experiment. Be sure you can access the DALN and other web resources. Wifi and networks fail. Computers crash. Planning for these inescapable technology perils becomes another useful learning outcome of this type of assignment.

My students consistently report these assignments require much more time, editing, and revision than a traditional text composition. Naturally, I chuckle at the prospect of my students spending hours in the computer lab working on a project for my course, but this can also lead to some serious crash-and-burn outcomes. If a student waits to the last minute or skips any of the preparatory assignments or training sessions, it shows up in the final product. The quality of work varies vastly between successful and unsuccessful final projects. Some students will not complete the project on time. Mistakes in grammar and hasty composition are much more apparent when displayed on a screen or video monitor. These hard lessons have a purpose as we teach our students to revise, revise, revise—the constant refrain of composition instructors. I relish the class meeting when my students proclaim that this work takes far more time than a written composition. It always happens, but not until the assignments have been turned in. Students are natural procrastinators and some may be fearful of a new challenge.

Hser and Ali both expressed a strong fear of technology before they completed their projects. Teaching students to overcome these fears and work early and often on the editing portion of the project is the key to a favorable end result. Recently, Hser came by my office to visit. I showed her drafts of this chapter, and she smiled broadly when she realized her work was a focus of my writing. Then she told me how often she had used digital projects in her other classes. Now a junior majoring in social work, Hser presented a video project in her sociology class. Ali has also used digital presentations in his political science courses. For them, learning to compose digitally has been a wise investment of time and effort. They assert it has made them better students and perhaps more marketable graduates.

In terms of achieving the broader goals of a composition course, this work requires students to identify and make use of engaging rhetorical strategies, analyze primary sources, develop stylistic strategies, attend to mechanical formatting, compose with attention to voice, tone, medium, and design. It demands drafting, revision, editing, and more revision. Students must master conventions of mechanics, graphics, visual design, and audio presentation. Instructors would bewise to include teachings on copyright, fair use, and intellectual property in the digital world.

I hope this work will inspire other teachers and scholars to take

up the work of addressing the unique needs of this student

population. We are facing the largest refugee displacement in

history. As nations grapple with how to address the safety and

security of more than 65 million people, it is critical we listen to

our refugee friends, students, and neighbors and support efforts to

document and preserve their experiences. This pedagogy answers Wendy

Hesford’s call: “We need to imagine a global citizenship free from

the language of fear and from the civilizing mission of providence,

a global citizenship that gives substance to human rights and

encourages intercultural and transnational dialogue” (2006, p. 795).

It is up to us as teachers to give our refugee students the access

along with the ability to transcend the powerful forces in media,

academia, and politics reducing them to a massive population of

passive victims. Syrian writer Lina Sergie Attar urges, “So many

people have disappeared, so many people are dead… That part of

history will be erased unless we are all working to keep it recorded

somewhere. That’s where I feel our work is, in between memory and

history” (qtd. in Burks, 2016). The literacy narratives of refugee

students in the DALN live as evidence of the struggles, memories,

and sacrifices of a massive portion of the global population. Their

work in the archive invites more scholarship about refugees and

refugee experience, while teaching all of my students about the

powerful sociopolitical forces shaping our world.

References

Ávila, J. & Pandya, J. (2012). Traveling, textual authority, and transformation: An introduction to critical literacies. In J. Ávila & J. Zacher Pandya (Eds.), Critical digital literacies as social praxis: Intersections and challenges (pp. 1–12). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Burks, T. (2016, April 11). Deconstructing the refugee narrative. The Reader Magazine. Retrieved from www.reader.us/deconstructing-the-refugee-narrative/

Cintron, R. (1997). Angels town: Chero ways, gang life, and rhetorics of the everyday. Boston: Beacon.

Drotner, K. (2013). Processual methodologies and digital forms of learning. In O. Erstad & J. Sefton-Green (Eds.), Identity, community, and learning lives in the digital age (pp. 39-56). Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Duffy, J. (2007). Writing from these roots: Literacy in a Hmong-American community. Honolulu: University of Hawaii.

Foucault, M. (1979). Michel Foucault on refugees: An interview from 1979. Retrieved from http://politheor.net/michel-foucault-on-refugees-an-interview-from-1979/

Freire, P. (1973). Education for critical consciousness. New York: Seabury.

Frost, A. & Malley, S. B. (2013). Multilingual literacy landscapes. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C .L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories That Speak to Us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Hawisher, G., Selfe C. L., Kisa G., & Ahmed, S. (2010). Globalism and multimodality in a digitized world: Computers and composition studies. Pedagogy, 10 (1), 55-68.

Hesford, W. S. (2006). Global turns and cautions in rhetoric and composition studies. PMLA, 121(3), 787–801.

Hesford, W. S. & Schell, E. E. (2017). Introduction: Configurations of transnationality: Locating feminist rhetorics. College English, 70, 461-470.

Horner, B. & Trimbur, J. (2002). English only and U.S. college composition. College Composition and Communication, 53(4), 594–630.

Jackson, M. (2002). The politics of storytelling: Violence, transgression, and intersubjectivity. Copenhagen, Denmark: Museum Tusculanum, University of Copenhagen.

Leudar, I., Hayes, J., Nekvapil, J., & Turner Baker, J. (2008). Hostility themes in media, community and refugee narratives. Discourse & Society, 19(2), 187–221.

Malkki, L. H. (1996). Speechless emissaries: Refugees, humanitarianism, and dehistoricization. Cultural Anthropology, 11(3) , 377–404.

McBrien, J. L. (2005). Educational needs and barriers for refugee students in the United States: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 329-364.

McDonald, M. (2013a). Keywords: Refugee literacy. Community Literacy Journal, 7(2), 95-99.

McDonald, M. (2013b). Emissaries of literacy: Refugee studies and transnational composition. (Doctoral Dissertation.) The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Retrieved from https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/133/

Nelson, M., Hull, G. A., & Young, R. (2012). Portrait of the artist as a younger adult: Multimedia literacy and “effective surprise.” In J. Sefton-Green (Ed.), Identity, community, and learning lives in the digital age (pp. 215-31). Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Norcia, M. A. (2008). Out of the ivory tower endlessly rocking: Collaborating across disciplines and professions to promote student learning in the digital archive. Pedagogy, 8(1), 91–114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/15314200-2007-026

Ochberg, R. (1996). Interpreting life stories. In R. Josselson (Ed.), Ethics and process in the narrative study of lives (pp. 97-112). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ochberg, R. (1994). Life stories and storied lives. In A. Lieblich & R. Josselson (Eds.), Exploring identity and gender: The narrative study of lives (pp. 113-144). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pandya, J. Z., Pagdilao, K. C., & Kim, E. A. (2015). Transnational children orchestrating competing voices in multimodal, digital autobiographies. Teachers College Record, 117(7), 1–32.

Pipher, M. (2002). The middle of everywhere: The world’s refugees come to our town. New York: Harcourt.

Selfe, C. L., & the DALN Consortium. (2013). Narrative theory and stories that speak to us. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories That Speak to Us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Sigona, N. (2016). The politics of refugee voices: Representations, narratives, and memories. In E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, G. Loescher, & K. Long (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of refugee and forced migration studies (pp. 369-79). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Whitlock, G. (2010). Soft weapons: Autobiography in transit. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wright, T. (2016). The media and representations of refugees. In E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, G. Loescher, K. Long, & N. Sigona (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of refugee and forced migration studies (pp. 461-62). Oxford: Oxford University Press.